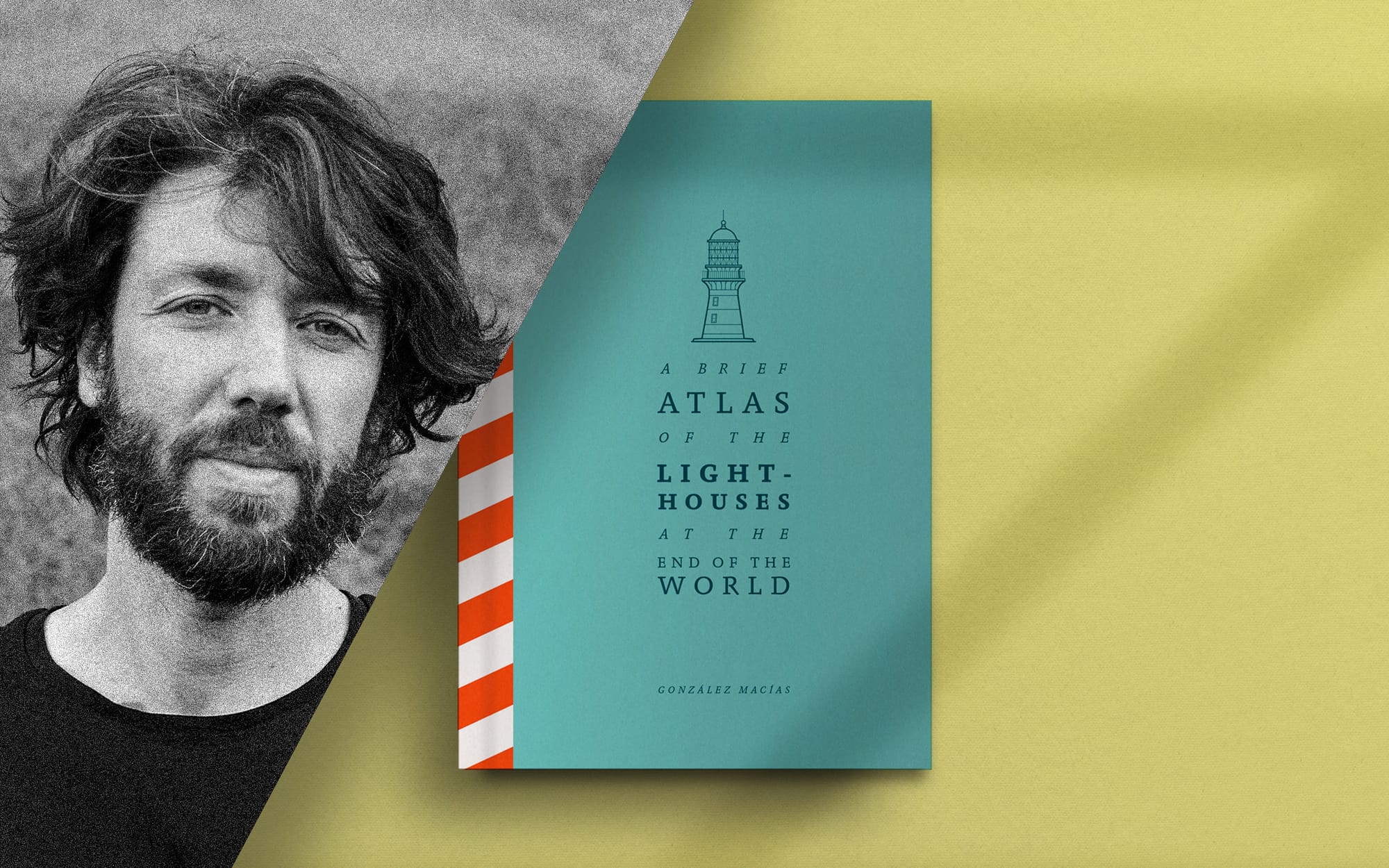

A Brief Atlas of the Lighthouses at the End of the World with Jose Luis González Macías

The Wild Beauty of Lighthouses

Lighthouses have captured the imagination of artists for many centuries. They are the solitary outposts of civilisations; the crucial saviours of human lives; astonishing engineering marvels.

‘There is something beautiful and wild in these impossible architectures’, writes Jose Luis González Macías at the beginning of his evocative book, A Brief Atlas of the Lighthouses at the End of the World. ‘These precious structures have been the homes and workplaces of men and women, whose romantic guardianship has saved countless lives from cruel seas.’

Inspired by this thought, several years ago González Macías began to compile a list of these enchanting buildings. He sought out structures old and new, some built of stone and others resembling wicker baskets, in locations from Ukraine to New Zealand. All of these lighthouses stood in remote locations, where they have often stood, like silent sentinels amid the waves, for many centuries.

A writer and designer by profession, González Macías produced graphic art, maps and plans for each of the lighthouses he selected. To draw out the characters of these structures still further he researched the human stories, the engineering peculiarities and rich legends that were attached to them. The result was a 150-page atlas, filled with lively accounts thirty-four distinct lighthouses.

This extract for Unseen Histories is taken from his chapter on Eddystone Lighthouse. Situated on an outcrop of perilous rocks, twelve miles to the south of the Royal Naval port of Plymouth, Eddystone has been a familiar sight for generations of sailors.

A lighthouse was first built here in the last years of the seventeenth-century warning mariners of all types against the dangers of the sea. It still stands today.

Unseen Histories

Can you explain where the idea for The Far Edges of the Known World came from?

Owen Rees

There is no quick or simple answer to that questions really. I have always been interested by things that do not fit. History or cultures that contradict the status quo or the accepted norms. Maybe it comes from living in Britain, which was one of those far flung places at the edge of the Greek and Roman world! Maybe it comes from my work for Bad Ancient, a website I run dedicated to fact checking common claims about the ancient world, and exploring the evidence to unravel misconceptions we all hold?

Either way, with this book I wanted to find a way to tell a different story of the ancient world; one that builds on the familiar narratives of civilisations like the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, but also pushed us further and further away from the Mediterranean Sea. A history that highlights the ‘world’ of the ‘ancient world’.

Unseen Histories

A figure you use to personify your argument is the poet Ovid. What meaning did you draw from the story of his banishment from Rome?

Owen Rees

The story of Ovid is often told from his own perspective. The unfortunate exile trying hard to be allowed to return home to Rome. His tale of woe is amplified by his own writings, which really try to hammer home how difficult his life is at the edge of the world.

What I found in his story was that his caricature of uncivilised lands echoed the way we, as historians, often present the ancient world beyond the influence of civilisations like Greece and Rome. Ovid invents a horrible world in which he lives, isolated and afraid on the west coast of the Black Sea. If we believed him, we would think that he was surrounded by uneducated fools who lived in a violent and chaotic land. But we know that the town he was exiled to, Tomis, was actually a Greek town. We know that he was given special exemptions from taxation. we also know that he was highly regarded in Tomis as a poet.

The icing on the cake comes from Ovid’s own complaints to his family in Rome that his place at the edge of the world would mean his own work would be forgotten — that he would be usurped as one of the great poets of Rome by less capable writers.

The reason we know this was his view, rather ironically, is because his work did survive. Living at the edges of the empire did nothing to ruin his reputation. If anything, it has enhanced it because he is remembered as one of Rome’s most famous exiles.

Unseen Histories

You note that the Greco-Roman centric view of the ancient world distorts our understanding of the history. Rectifying this is clearly one of the aims of your book. Are other scholars attempting a similar act of rebalancing too?

Owen Rees

Absolutely yes. There is amazing research constantly being published that is trying to move us away from an over reliance on the Greco-Roman writers and their explanation of other cultures.

This is coming in a variety of ways. Archaeology is effectively smashing the dominance of written evidence and unveiling life in places that our Greek or Latin authors knew nothing about. Indeed, this fed much of the book: settlements like Bilsk in northern Ukraine, Karanis in Roman Egypt, or Co Loa in northern Vietnam, these do not appear in the grand historical narratives from ancient Greece, Rome or China! There is also a fascinating trend which is exploring the interconnected nature of the ancient world through trade and travel.

But even closer to ‘traditional’ ancient history, there is a real push to try and offer different perspectives towards the classical world. Whether it is from the perspective of outside cultures, or through the experience of previously overlooked groups such as women, children, workers, or the enslaved. This is not about rewriting history but rather expanding and growing our knowledge to offer a more well-rounded understanding of this fascinating historical period.

Unseen Histories

Your story begins deep in pre-history with the first traces of human activity in east Africa. But instead of following the usual trail northward towards Mesopotamia you linger at Lake Turkana in Kenya. What is the significance of this place?

Owen Rees

One of the big questions that arose from the very start of this book was who defines what is at the edge of the world, or indeed at the edges of history? The human story regularly follows the trajectory of the ‘civilising’ path; the mastery of agriculture, the birth of urbanisation, the invention of writing and so on. But this omits many cultures that never went down that path.

Lake Turkana is considered one of the cradles of human history, so I wanted to explore what was going on there while the more conventional stories of ‘civilisation’ were being written in places like Mesopotamia and Egypt. What we see are the same themes that permeate the entire book: stories of family, identity, community building, ingenuity and adaptability, but also othering, conflict, and the horrors that we can inflict on each other.

If we want to understand and appreciate the story of humanity, we need to start including the histories of places like Lake Turkana and not just settle for a narrow focus on the big, dominant ancient cultures.

Unseen Histories

When it comes to Ancient Greece, we’re quite comfortable at locating Athens as its centre. But where were its edges? How far across the global did Greek knowledge spread?

Owen Rees

The Greek world was larger than you’d think! Even if we just look at where Greek settlements were located, we have sites that cover most of the Mediterranean: the coast of Iberia and southern France, all the way to southern Turkey, and north up to Crimea in the Black Sea.

Greek cultural influence also spread with trade and went beyond these coastal sites, so Greek wine amphorae and other artifacts have been found in northern Ukraine for instance. In terms of language, we see the Greek language being used all over, as far south as Aksum even, a powerful kingdom in Ethiopia and Eritrea – but interestingly we see the importance of Greek wane in place of the local script Ge’ez as the ancient Mediterranean comes to an end and the golden age of Aksum reaches its height!

After the conquests of the Macedonian king Alexander the Great, we see the zenith of Greek cultural influence, which included much of the old Persian Empire such as Egypt, modern Iran and into what is now Pakistan.

In fact, something that I find more fascinating is that Greek learning and culture was also incorporating the learning of other societies as well. This is something the Greeks were very aware of, whether it be knowledge from Egypt or India, or the wisdom of the Scythians, Greek writers did not just see these lands as somewhere in which to impose their own sense of the world.

Unseen Histories

Borderlands are a continual draw throughout the book, places that were once bluntly conceived as spaces where civilization and barbarism met. But it is only really with the Romans that any formal ideas of land borders began. Is this true?

Owen Rees

That may be a slight simplification, but I think, in terms of scale and ideological underpinning, the Romans are the first to really give a sense of large scale ‘borders’ that we might recognise today. Of course we see borders at places like Egypt, who created a series of forts along the Nile down to Nubia, but the scale of the Roman Empire just really cements for us the more modern idea of controlled borders.

But I suppose, this is also a bit of a fallacy. Maybe one of our own making? We do like to draw out the Roman Empire like a firm picture on a map, don’t we? But it was not all firmly defined like at Hadrian’s Wall. These boundaries or borders were often moving and fluctuating in real terms.

Unseen Histories

One of your stated aims is to ‘capture narratives’ that are often ignored. Can you give a favourite example of one of these that is covered in the book?

Owen Rees

Oh, there are so many to choose from! There is the elite Egyptian woman Geheset, who is one of the earliest known examples of cerebral palsy in the historical record. Or the Scythian, nomadic philosopher Anacharsis who challenged the great lawgiver of Athens, Solon, about his new laws.

There are the Trung sisters of Co Loa, Vietnam, who stood defiantly and resisted the imperial power of Han China, leading a large army in uprising. Or a personal favourite is that of Zarmanochegas, a Buddhist monk who came to Athens in the time of the Roman emperor Augustus and set himself on fire (dying in the process) as an act of faith. The Athenians were so in awe of what they saw, they built him a tomb and, in the inscription, declared him immortal in accordance with the customs and laws of India!

But sometimes the stories that capture your interest are ones that don’t always have a clear ending. In the Greco-Roman town of Karanis, in Egypt, we see the petition of a young, illiterate orphan called Aurelia Tapaeis, who had her inherited land stolen and sold off by two men.

We do not know how the petition went, hopefully it was successful, nor do we know anything else about her really. Her petition highlights the dangerous position orphan children could find themselves in - open to exploitation from adults - but it also shows the agency and empowerment available to young people. The fact that she was making a legal petition on her own behalf, standing up for her own rights; this is a side of the ancient world we do not see very often!

Unseen Histories

A scholarly challenge you face is the reductive nature of the source material. Different peoples and quite contrasting geographies bundled often together into one. How did you respond to this?

Owen Rees

With great difficulty, but that is the job! There are times to tackle and challenge the written evidence. To try and untangle it and see what our authors are actually saying, and about whom. Sometimes they are not talking about specific cultures they have seen but are offering a fantasy culture that often contrasts with their own.

So, we are learning more about their culture than the so called ‘barbarian’. To really get to grips with some of these borderland groups it is necessary to move away from a reliance on writing as our primary form of evidence – a hard habit to break, I must admit. But the advancement in archaeological research is just phenomenal and can be used in amazing and innovative ways, if we as historians are willing to ask slightly different questions.

But sometimes we have to be honest and say when we are not sure who or where is being discussed here. This was particularly true with ancient geography where places like Libya could mean all of Africa except Egypt, but it also had a specific region called Aethiopia which was vaguely described as being to the south … somewhere.

We have a similar problem with how much of the world wass included in the geographic region of ‘India’. So, all you can do is try to find the consistency in the ancient writer themselves and try not to assume every other ancient writer agreed!

Unseen Histories

There’s an evocative section when you imaginatively recreate the journey of a tradesman from Athens to a hill fort called Bilsk. Can you tell us about the significance of this place?

Owen Rees

Bilsk is the perfect place to unravel our assumptions about the ancient world. It is located in central Ukraine and is the largest hill fort in Europe. The scale of this place is astronomical. The fort is actually a large wooden wall that connects three smaller forts. The walls themselves are over 33km – for context, the 3rd century CE walls of Rome measure a measly 19km in comparison. Its footprint is almost 5,000 hectares, making it double the size of Imperial Rome!

So who lived there? The first inhabitants were a migrated people from Central Europe, but they were soon joined by the Scythians. It may seem odd to think of the Scythians, a famously nomadic society according to the Greeks, living at this fort but recent studies of Scythian burials in the region suggest that they were not living nomadic lives anymore. So perhaps the Greeks got that one wrong? Or maybe they overgeneralised?

As a location it was perfectly placed to act as an interchange between life on the open plains of the Steppes to the east, central Europe to the west, the Black Sea to the south and down into the Mediterranean.

As a result, we find proto-Celtic artefacts on site, as well as Scythian and Greek too. The most exciting find has to be an elite woman who was buried with items that came from Egypt – over 2,000km away! So Bilsk epitomises so many of the themes of the book: co-existence, global trade, the interconnected nature of the ancient world and, to top it off, how we can’t always trust our ancient Greek and Roman writers.

Unseen Histories

Bilsk might seem a novel location for a book on the ancient world, but your narrative progresses much further east than this, all the way to Co Loa in modern-day Vietnam. What link, if any, is there between this distant place and the familiar Mediterranean one?

Owen Rees

Our Roman writers knew about the world beyond India, but only conceptually. Their descriptions of the Malay peninsula and the Gulf of Thailand are vague but identifiable. There is mention of a market town that lay beyond the Gulf of Thailand, to the southeast, which sat next to a major river that ran north. The name is given as Cattigara, but scholars believe it is likely to be the ancient Vietnamese city of Oc Eo, which sits on the southwestern coast of Vietnam and is in the Mekong Valley. This link is potentially corroborated by finds of Roman goods as Oc Eo, such as jewellery and medallions bearing the likeness and names of two Roman emperors!

Co Loa itself is an amazing place with such a vivid history. Located in the northeast of Vietnam, its relationship with the Mediterranean is undetermined as yet. However, sources from Han China do describe an alleged envoy from Rome coming to the Han imperial court in the 2nd century CE.

On their journey, the Roman envoys (or more likely, traders) landed in a region called Rinan, on the east coast of Vietnam. Co Loa is not identifiable in the story, but the presence of Roman traders and Roman goods in Vietnam is undeniable! 𖡹

He studied at the universities of Reading and Nottingham before completing his PhD at Manchester Metropolitan University in 2018. Previously, Owen held postdoctoral fellowships at the Institute of Medical Humanities at the University of Durham, and a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship at the University of Nottingham.

Owen is also the founder and lead editor of badancient.com, which brings together a growing network of specialists to fact-check common claims made about the ancient world.

The Far Edges of the Known World

Bloomsbury, 13 February, 2025

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1526653789

"A wide-ranging tour of the fringes of the ancient world"

– The Times

What was it like to live on the edges of ancient empires, at the boundaries of the known world?

When Ovid was exiled from Rome to a border town on the Black Sea, he despaired at his new bleak and barbarous surroundings. Like many Greeks and Romans, Ovid thought the outer reaches of his world was where civilisation ceased to exist. Our fascination with the Greek and Roman world, and the abundance of writing that we have from it, means that we usually explore the ancient world from this perspective too. Was Ovid's exile really as bad as he claimed? What was it truly like to live on the edges of these empires, on the boundaries of the known world?

Thanks to archaeological excavations, we now know that the borders of the empires we consider the 'heart' of civilisation were in fact thriving, vibrant cultures - just not ones we might expect. This is where the boundaries of 'civilised' and 'barbarians' began to dissipate; where the rules didn't always apply; where normally juxtaposed cultures intermarried; and where nomadic tribes built their own cities.

Taking us along the sandy caravan routes of Morocco to the freezing winters of the northern Black Sea, from Co-Loa in the Red River valley of Vietnam to the rain-lashed forts south of Hadrian's Wall, Owen Rees explores the powerful empires and diverse peoples in Europe, Asia and Africa beyond the reaches of Greece and Rome. In doing so, he offers us a new, brilliantly rich lens with which to understand the ancient world.

"A true tour of horizons, the ancients' and our own. Exploring ancient worlds beyond Greece and Rome, Owen Rees illuminates the dimmer corners of the Mediterranean as well as societies on other sands and seas, from Kenya to Ukraine. Fascinating questions arise: When is a border a boundary? When is a site a city? And when are people 'classics'?"

– Josephine Quinn

"This is a powerful and wide-ranging account of life at the edges of the known world ... From Hadrian's Wall to Co Loa in Vietnam and the Christian town of Aksum in Ethiopia, Rees takes us on a journey of discovery that never fails to be engaging ... A natural storyteller"

– Helen King

With thanks to Ben McCluskey