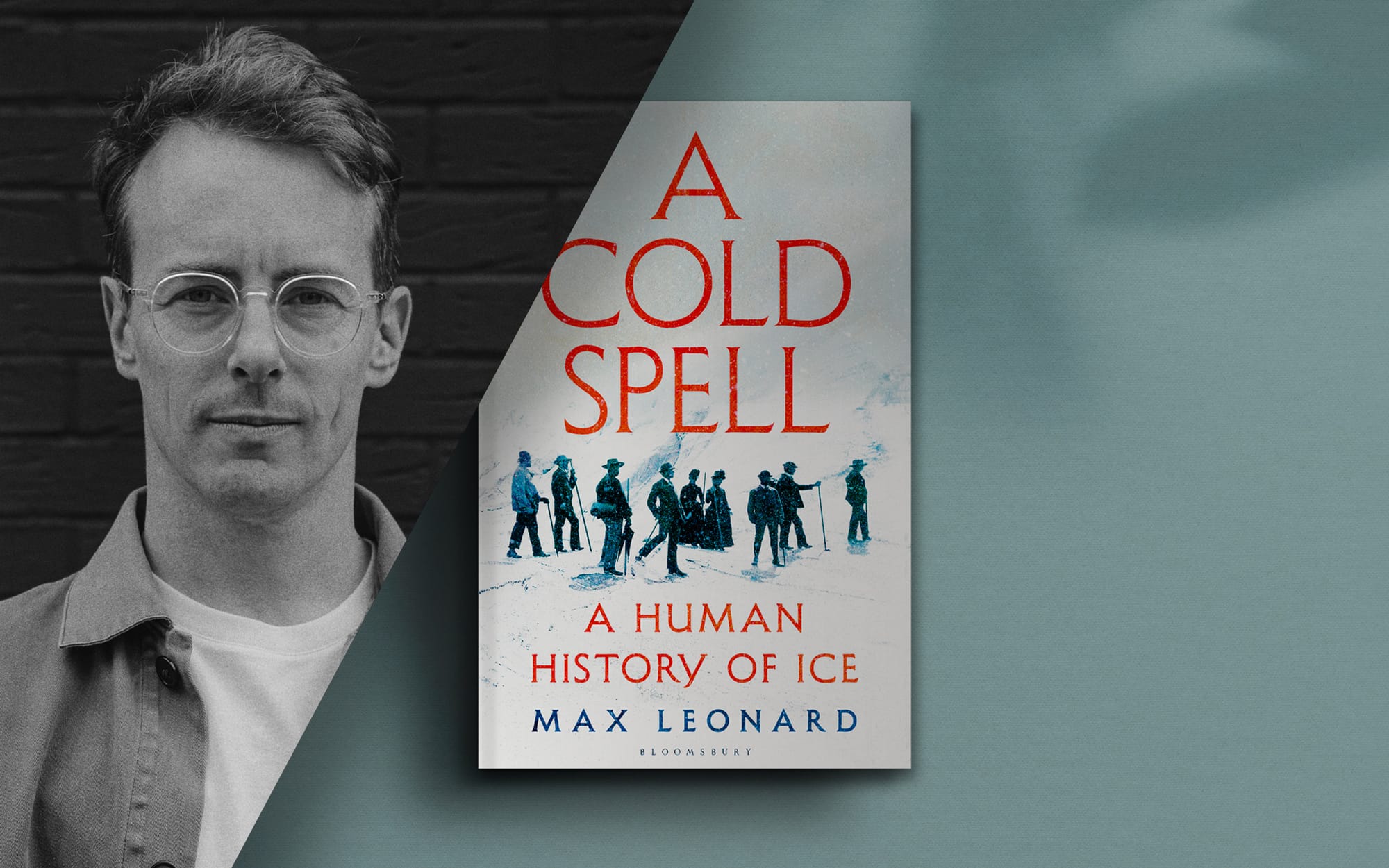

A Cold Spell with Max Leonard

Max Leonard on the human history of ice

To look at a block of ice is to see, in simple terms, a compound made up of hydrogen and oxygen atoms. But as Max Leonard shows in his new book, A Cold Spell, ice contains much more than that.

Leonard is interested in our human relationship with ice. This is a relationship that stretches right back into deep time.

From cave paintings and ice grottos, to frost fairs and frozen bodies, in A Cold Spell Leonard relates an enchanting and often surprising historical story.

Unseen Histories

At one point in A Cold Spell you write memorably about Samuel Pepys’s first encounter with ice skaters. Do you recall your own very first experience of ice?

Max Leonard

I’m not sure if it was my first experience, but one of my very early memories is of a cold spell one winter, of going to the park in the frost and walking on to one of the ponds, which had frozen solid, holding one of my parent’s hands. This was in the early 1980s – ponds don’t freeze over very often in London any more!

Unseen Histories

Can you explain what you set out to achieve in A Cold Spell?

Max Leonard

I first got an inkling of the book in a Newcastle pub one hot summer afternoon, watching a news report on the television above the bar about the melting ice sheet in Greenland, and viscerally feeling the disconnect between the ice on the screen and the ice in my glass. So one of the things I set out to do was to try to inspire some sense of connection with the planetary ice that is melting so very quickly – but mainly very far away, in the corners of our collective vision – by celebrating the ice that those of us in temperate parts of the world encounter every day in the normal course of our lives, which is often figuratively and literally almost invisible to us.

After that moment, as I researched the rich history of how we have used ice, I began to realise how fundamental it has been to our societies and to our understanding of ourselves. How we have used it to build our civilisations and, in turn, how our interactions with ice have shaped us. It is something we have thought about, debated and experimented with. Without ice, we would not feed ourselves or heal our sick as we do. Science would not have progressed along the avenues it has. Without ice, our towns and cities, countryside and oceans would be very different, and our galleries and libraries would be missing many masterpieces.

In the early days, ice was completely inexplicable and sort of miraculous; I wanted to restore some of that wonder.

Unseen Histories

The book is crammed with intriguing stories. Some of the early ones belong to the discovery of ‘ice mummies’ in the Alps and Siberia. Can you tell us about one of these?

Max Leonard

Ötzi the Iceman was perhaps the first so-called ‘ice mummy’, and certainly the most famous. He was found in 1991 by two German hikers near a trail at over 3,000 metres altitude in the Alps on the border of Austria and Italy. At first, it wasn’t believed he was very old, but it was immediately clear to the first archaeologist who examined him when he was brought Innsbruck that he was ancient – over 5,000 years old in fact.

Because he fell into an ice gully, his body and all his possessions were exceptionally well preserved – fur, wood and other materials, even what he had for dinner – giving us a window into the lives of Europeans in the proto-historic past. As with all the ice mummies, ice collapsed time, bringing us into proximity with lives we could never otherwise have known.

Unseen Histories

Other things – perhaps most notably an entire woolly mammoth – have appeared out of the ice too. With temperatures rising do archaeologists anticipate more finds in the years ahead?

Max Leonard

Up until the late 1930s, the discipline of glacial archaeology did not even exist: it was not understood that the artefacts being found were emerging from melting glaciers and ice patches. There has been a big increase in finds, and it is an exciting field of study, albeit in a bittersweet way. It is, in two profound senses, a race against time. Given the speed with which glaciers (and ice patches, etc.) are now receding, soon there won’t be much left to melt. The other urgency stems from the fragility of the ice’s cargo: once re-exposed to the air, finds can deteriorate and decay frighteningly quickly.

Unseen Histories

We mostly think of ice as being a static thing. It exists on mountains or at high latitudes. But you also write about the capitalist adventurers who transported ice across vast distances. This seems very improbable but it was financially lucrative, wasn’t it?

Max Leonard

By the 1820s ice was arriving in London from Greenland and Norway, to furnish the tables and chill the drinks of an elite few. It was much purer and more abundant than anything people could scrape together in the UK. As the century progressed and the quantities increased, it democratised – though Queen Victoria stuck with lake ice until well after manufactured ice became available in the second half of the century.

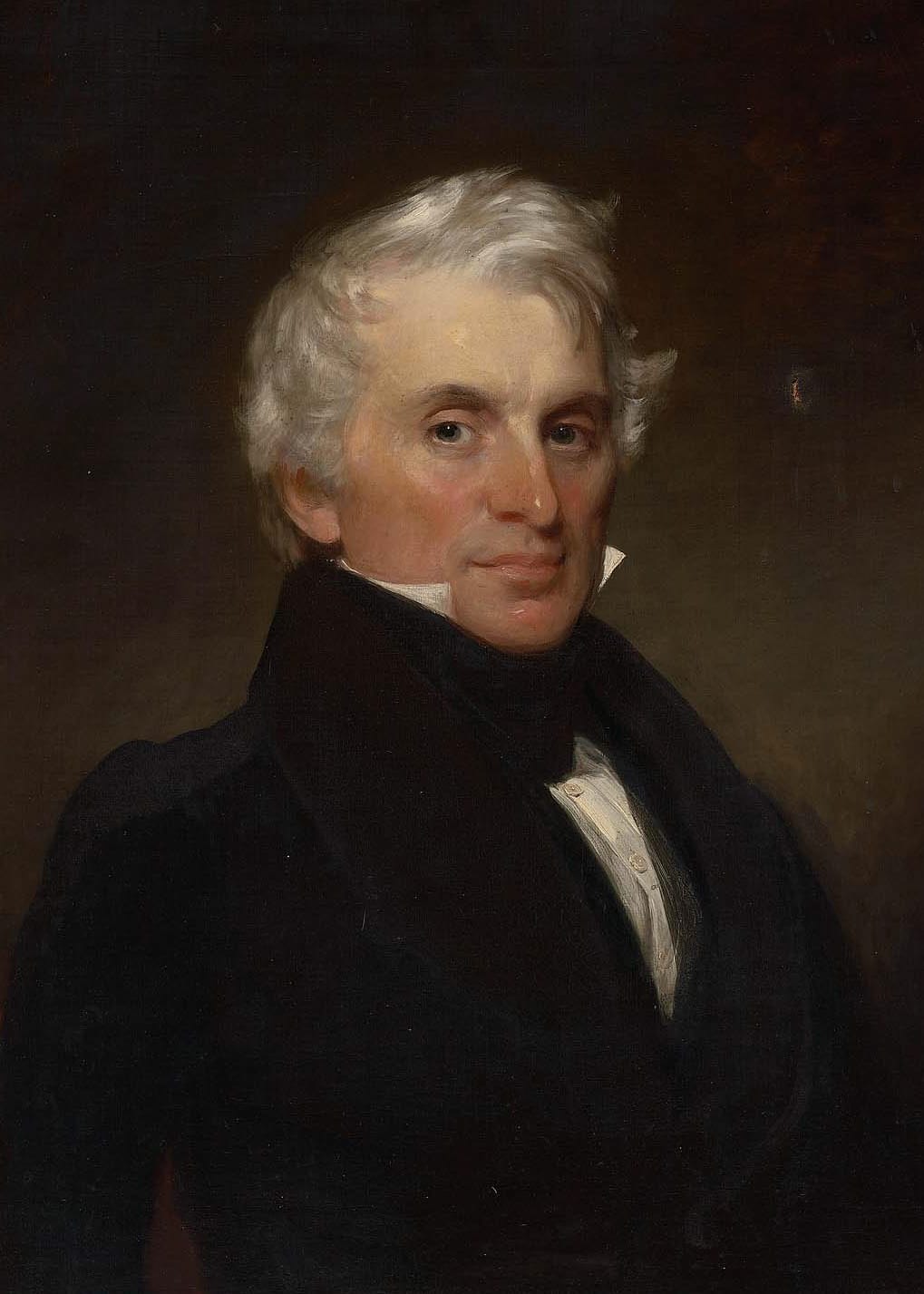

However, the real 'Ice King' was Frederic Tudor of Boston, USA. From around 1805 he attempted to export ice cut from the lakes of Massachusetts to hotter climes, including the Caribbean, the cities of the American South and India. A first successful shipment of 100 tons arrived in Calcutta in 1833 – 144 tons had been loaded in Boston – destined to cool the drinks of the British colonial rulers. Tudor seems something of a wheeler-dealer, and made and lost great amounts of money. He is often called ‘America’s first millionaire’, but this at least in part down to the waterfront property he bought.

Unseen Histories

It seems that the Romantics had a particular affinity for ice. Is this right?

Max Leonard

In 1816 Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (not yet Shelley’s wife) travelled to Switzerland. What they saw there, and at the Mer de Glace glacier above Chamonix, inspired icy imaginings in poems by Byron and Shelley, and in Mary’s Frankenstein in particular. As with the intrepid polar explorers battling to find a north-west passage to the Orient, the ice perhaps proved a blank canvas on which they could project all their desires… and fears.

Unseen Histories

As well as being aesthetically appealing, ice was frequently put to practical use too. Is it true that it was once used as an anaesthetic?

Max Leonard

Ice was commonly used as an anaesthetic, even into the mid-nineteenth century when gas was available, as early gas technology was rudimentary and patients were as likely to drift off forever as wake up. Dentists in Harley Street used ice when extracting teeth and a doctor called James Arnott pioneered the use of ice mixed with salts, which pushed the temperature even lower. He put his ice-and-salt mixture into a small pig’s bladder, which could then be held against the area that needed treatment to produce numbness. He removed warts from all sorts of places this way, as well as treating ulcers and hernias and performing knee operations.

Unseen Histories

Another use – one of the most eccentric episodes in the book – relates to the proposal for a ‘bergship’ that would seemingly end the Battle of the Atlantic. Can you tell us about this?

Max Leonard

A huge problem for Winston Churchill during the Second World War was the amount of shipping being lost to U-boats in the North Atlantic. An advisor to Lord Mountbatten named Geoffrey Pyke dreamed up a scheme to create an aircraft carrier out of ice, which would allow planes to refuel and provide air cover. Despite the outlandish nature of the idea, Mountbatten and Churchill were enthusiastic, and Pyke’s team of scientists were installed in a frozen-meat locker under Smithfield Market in London, where they developed a wood-pulp-reinforced ice that they named ‘Pykrete’. For a variety of logistical and political reasons full-size bergships did not see the light of day, but a scale model weighing a thousand tons was built in a lake in Canada.

In one glacier, the Marmolada, these developed into an Eisstadt – an ‘ice city’ – with over twelve kilometres of tunnels housing barracks, an infirmary and even a chapel. It was dangerous down there but preferable to the howling gales, avalanches and snipers above.

Unseen Histories

Ice also featured in the First World War, when battles were fought in frozen tunnels high in the Alps. Were you able to explore these locations during your research?

Max Leonard

I did travel to the Alps to walk the glaciers of the so-called ‘White War’, where Italian and Austro-Hungarian soldiers faced off frequently at more than 3,000 metres above sea level. Long supply lines were needed to keep the men in these high encampments provisioned, and these were vulnerable to attack, so an Austrian engineer called Leo Handl had the bright idea to dig tunnels through the glacier where men would be safe from enemy fire. In one glacier, the Marmolada, these developed into an Eisstadt – an ‘ice city’ – with over twelve kilometres of tunnels housing barracks, an infirmary and even a chapel. It was dangerous down there but preferable to the howling gales, avalanches and snipers above. The tunnels were constantly moving as the glaciers shifted, and do not survive now, but all along the old front lines are fragments of shells, barbed wire, planks and metal fittings, which are melting into daylight as the ice recedes.

Unseen Histories

You write about great works of art that have been inspired by ice, from Hendrick Avercamp’s paintings to Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat's Cradle. Do you have a particular favourite?

Max Leonard

I think Cat’s Cradle and the facts behind it were my favourite. It tells the story of how a new form of ice that is solid above 0 ºC falls into the hands of an ageing tinpot dictator, and of the catastrophic consequences when it is unleashed on the world. The science behind it was inspired by Kurt’s brother Bernard, who worked with General Electric after the Second World War on ice formation in clouds and how this might be used to influence the weather! But Kurt famously had survived the firebombing of Dresden, and the novella was published in 1963, at the height of the Cold War, so the ice also stands in for a kind of apocalyptic technological dread. It’s a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of human intervention into natural systems, which still should resonate today 𖡹

A Cold Spell: A Human History of Ice

Bloomsbury, 9 November, 2023

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-1526631190

"Brightly written, nimbly researched and really quite delightful"

– Peter Moore

Ice has confounded, delighted and fascinated us since the first sparks of art and culture in Europe and it now underpins the modern world. Without ice, we would not feed ourselves or heal our sick as we do, and our towns and cities, countryside and oceans would look very different. Science would not have progressed along the avenues it did and our galleries and libraries would be missing many masterpieces.

A Cold Spell uses this vital link to understanding our past to tell a surprising story of obsession, invention and adventure - how we have lived and dreamed, celebrated and traded, innovated, loved and fought over thousands of years. It brings together a sacrificial Incan mummy, Winston Churchill's secret plans for unusual aircraft carriers, strange bones that shook Victorian beliefs about the world and a macabre journey into the depths of the human body. It is an original and unique way of looking at something that is literally all around us, whose loss confronts us daily in the news, but whose impact on our lives has never been fully explored.

"In a bracingly original book, Max Leonard makes something we all take for granted into an absorbing pathway into history, geography and science . . . A highly readable feast of insights and surprises . . . As the earth warms threateningly, there could hardly be a more pertinent time for a story like this"

– Michael Palin

"A book of limitless fascinations, an elegant and subtle accounting of how ice has shaped and changed human life, and how in turn humans have imperilled the existence of icy places"

– Olivia Lang

With thanks to Brittani Davies. Author Photograph © Emily Maye