A Very American Santa Claus

Emily Kern traces the provenance of a modern folk hero

Few things seem as settled and secure as our picture of Santa Claus. He is the jolly old man with the flowing white beard who sweeps the skies on Christmas Eve in his jingling sleigh.

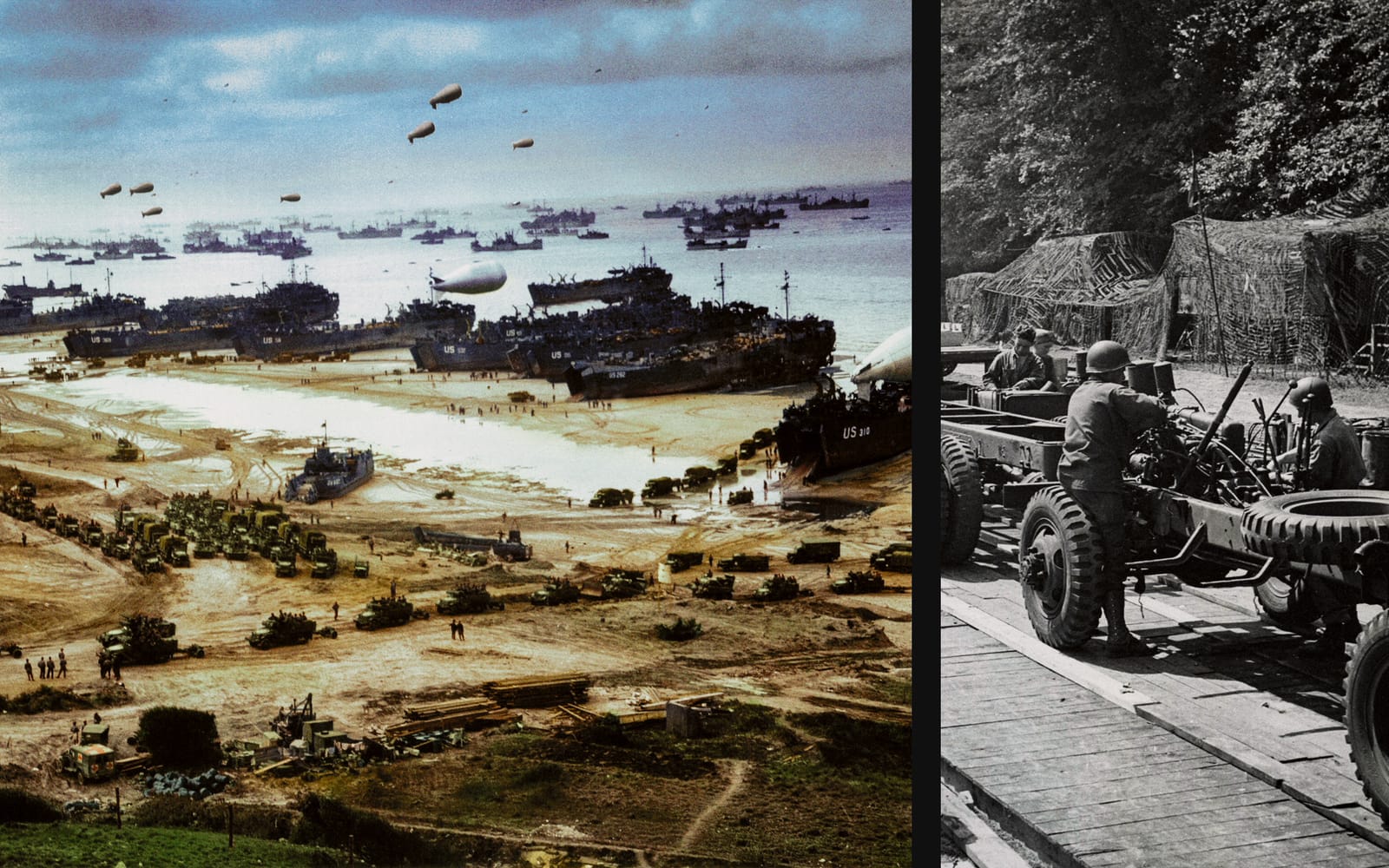

Contrary to popular belief, Fred Mizen’s classic Red Santa Claus featured in Coca-Cola’s advertising from the 1930s continues a long tradition of portrayals of the modern day Father Christmas.

Words by Emily Kern

Remastered Photographs by Jordan Acosta and Tetyana Dyachenko

Evolving from the 4th century Greek bishop Saint Nicolas in medieval Western Europe, the figure of Father Christmas as a large man was pictured in earthy green and scarlet robes as early as Henry VIII’s England in the 16th century. Luther’s German Reformation saw the re-casting of Saint Nicolas as Weihnachtsmann, the secular gift giver, whose popularity soared in the Victorian era and spread to the United States where the German born cartoonist Thomas Nast replaced Father Christmas’ hood with a hat, and changing the tan coat to a shorter, redder coat.

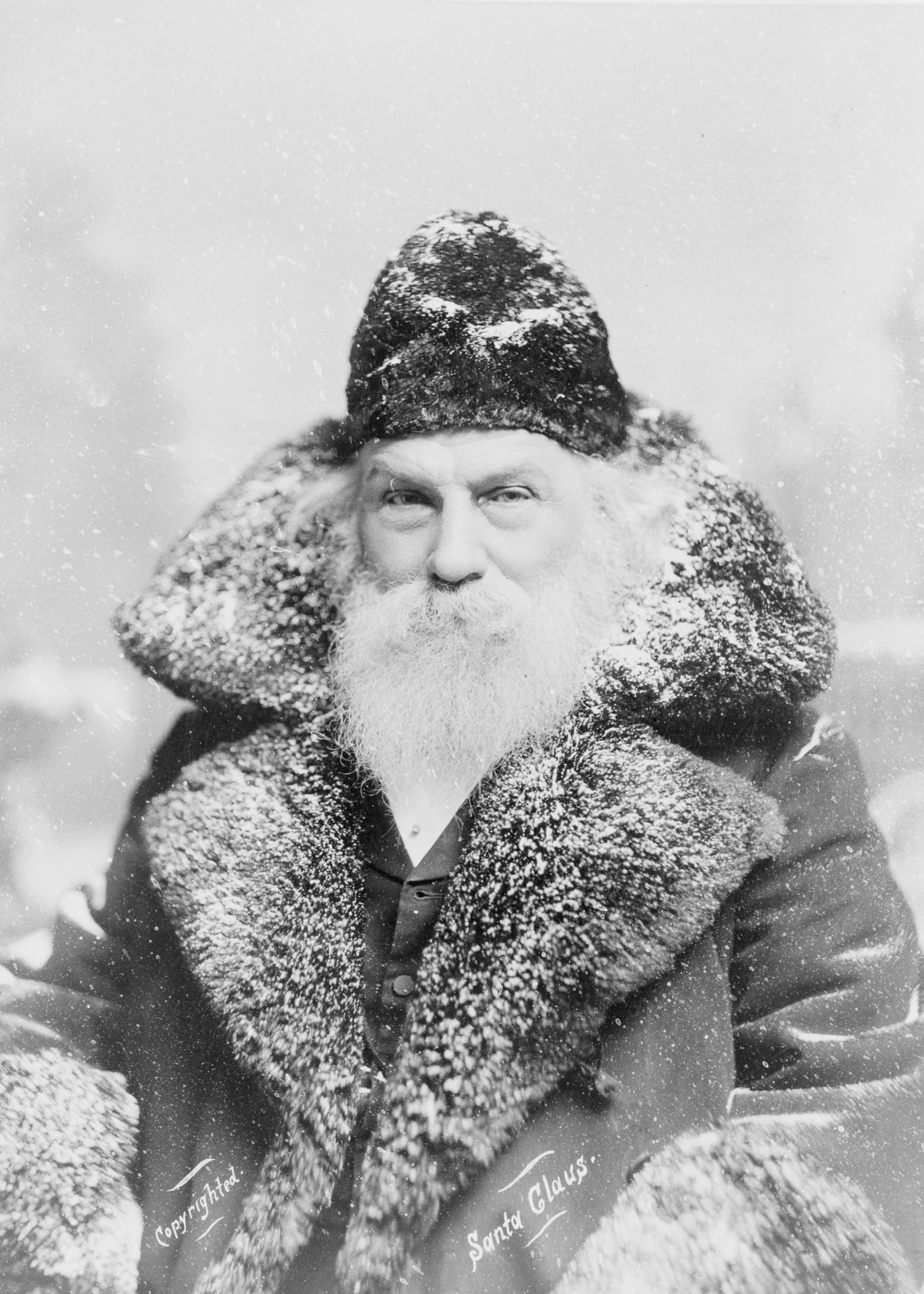

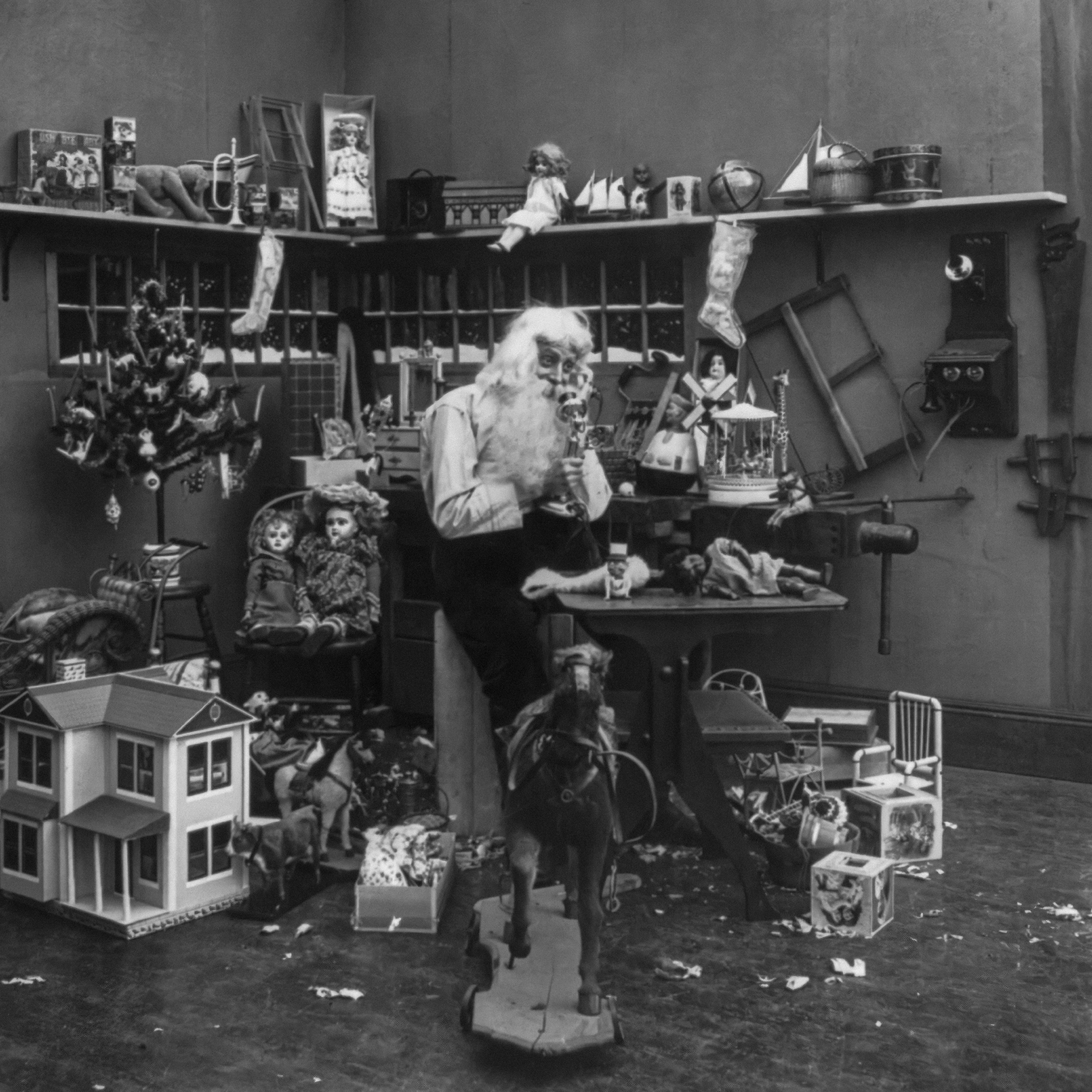

Santa Claus. Man portraying Santa Claus, half-length, facing front, in snowy scene, 1895. (⇲ Library of Congress) Colourisation Jordan Acosta

Much of this story can be glimpsed in this late Victorian photograph. Santa’s eyes twinkle benevolently over his beard. He is dusted with snow, which could equally be a hint of the North Pole or of his grand nocturnal ride. But there are also some unfamiliar elements in this portrait. Our research suggests that the sitter is wearing a fur-lined tan coat instead of the traditional red. His hat is a far more modest affair than the Phrygian cap with white bobble we recognise today. These details are a reminder that at the time that this photograph was made – most likely in the mid-1890s – Santa’s image was still very much in the process of emergence.

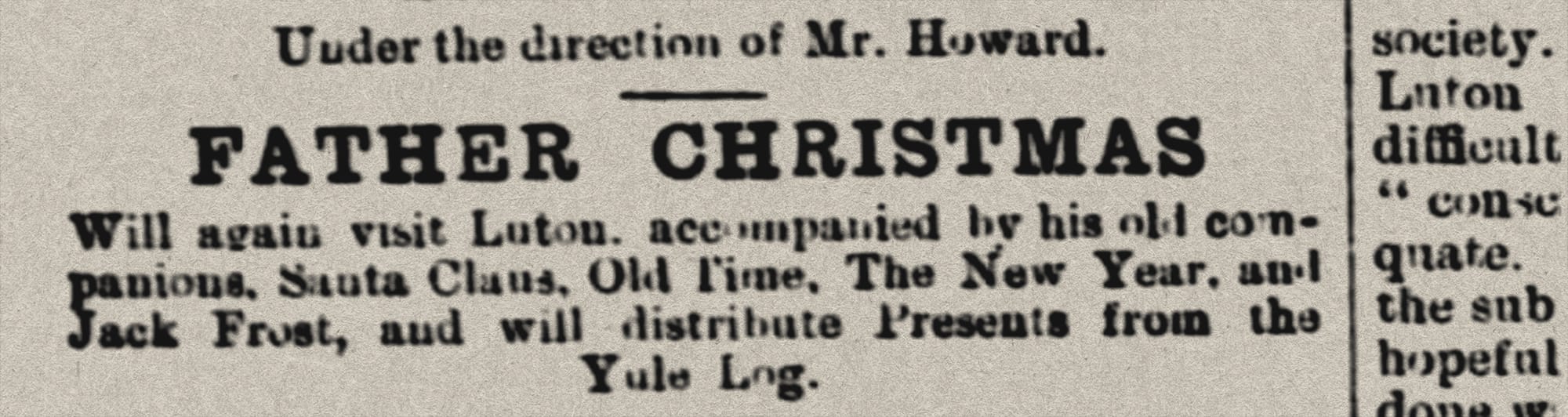

In fact, few Britons would have heard of this man called ‘Santa Claus’ a generation earlier. In the 1850s, ideas about Christmas were instead shaped by the writings of Charles Dickens along with the customs, ceremonies and superstitions of a time long past. The name ‘Santa’, for instance, does not feature once among the pages of yule logs, mince pies, carols, plum puddings and hampers in Thomas Hervey’s Book of Christmas (1845). The only references to a ‘Santa’ that are to be found in the British newspapers of the time are to ships and racehorses, whose owners seem to have enjoyed the euphony of a mellifluous name.

During this era, Father Christmas’ green coat was very much on the decline, replaced by the far more favourable depictions of Santa Claus in a red coat, along with an ever-increasing number of goods from distant parts of the planet, came mentions of this new seasonal figure. As Christmas approached, eager merchants would announce in their newspaper adverts, ‘Santa Claus Is Coming!’.

L-R: [Caught in the act]. Man dressed as Santa Claus seated on model of chimney smoking long pipe and blowing circles of smoke. c.1900. (⇲ Library of Congress) / [Grace Coolidge, Santa Claus, and children next to Christmas tree]. (⇲ Library of Congress) Photograph Harris & Ewing, December 1927, United States / A US Navy sailor dressed up as Santa Claus climbs the smokestack of the repair ship USS HECTOR. (⇲ US National Archives) Photograph JO3 George Hammond, December 1986

But who exactly was Santa Claus?

For most the touchstone character was ‘Old Father Christmas’, who had long been known for his beard, good humour and luxurious green robe. Santa, from the very start, shared many of these characteristics. But for most Victorians the two remained quite separate figures.

This perspective is also captured in this festive poem from a few years earlier. Titled The Children’s Christmas Eve (1882), it describes the fevered atmosphere of a nursery on Christmas night. Again, it is not clear whether Santa and Father Christmas are one individual or two:

When they hung up all the stockings,

They declare they cannot sleep,

But will lay away and try at

Santa Claus to get a peep.

Will he come in by the window.

Down the chimney, through the floor,

Or, with his great sack of treasures,

Will he come in at the door?

Will he come like Father Christmas,

Robed in green, and beard all white?

Will he come amid the darkness?

Will he come at all to-night?

Little eyes grow very weary,

Words grow few and far between.

When they wake on Christmas morning,

No one Santa Claus has seen.

Santa Claus might have been elusive, but his story was emerging fast. In 1886, in a jaunty Christmas Day essay, The Coleraine Chronicle set down a remarkably comprehensive account of Santa’s story, which remains familiar to us today:

25 December 1886

If the imagination of the child—and ‘a boy’s thoughts are long, long thoughts;—could reveal its Christmas secrets, doubtless we should see it shaping for his wonder the strange woods of Santa Claus, in which the verdure is all of Christmas trees lit with tiny tapers, and blossoming, beyond apple trees in June, with rare and beautiful gifts, while yet from out that blooming realm of everlasting green the monarch, muffled from the cold, comes gliding over the hoar frost with air reindeers tinkling in the chilly moon.

To share that midnight ride, to behold the multitudinous stockings, and to return to the realm of eternal Christmas gifts, is a vision not beyond the darling imagination of the boy who, in the joy of the Christmas morning twilight, as he feels the forms before seeing the beauty of his gifts, looks beyond the gifts to the region whence they, as in touching ivory, and beholding pearls and smelling spices he is rapt into a far Persian and African and Indian world, sees birds-of-paradise, and saunters under palms.

By the 1890s, a detailed biography of Santa Claus was in circulation. This might have fixed his home among the strange woods of the north, but in reality his identity was composed from a blend of quite different geographies and cultures.

From Britain itself came the legend of Father Christmas. From Germany in the east came the influence of Saint Nicholas who was known for his love of children and for his indiscriminate acts of generosity. Then, from across the Atlantic, and the United States of America, came something else. In that young nation – one that was far less cluttered with ancient traditions – there was more scope for a new figure to develop.

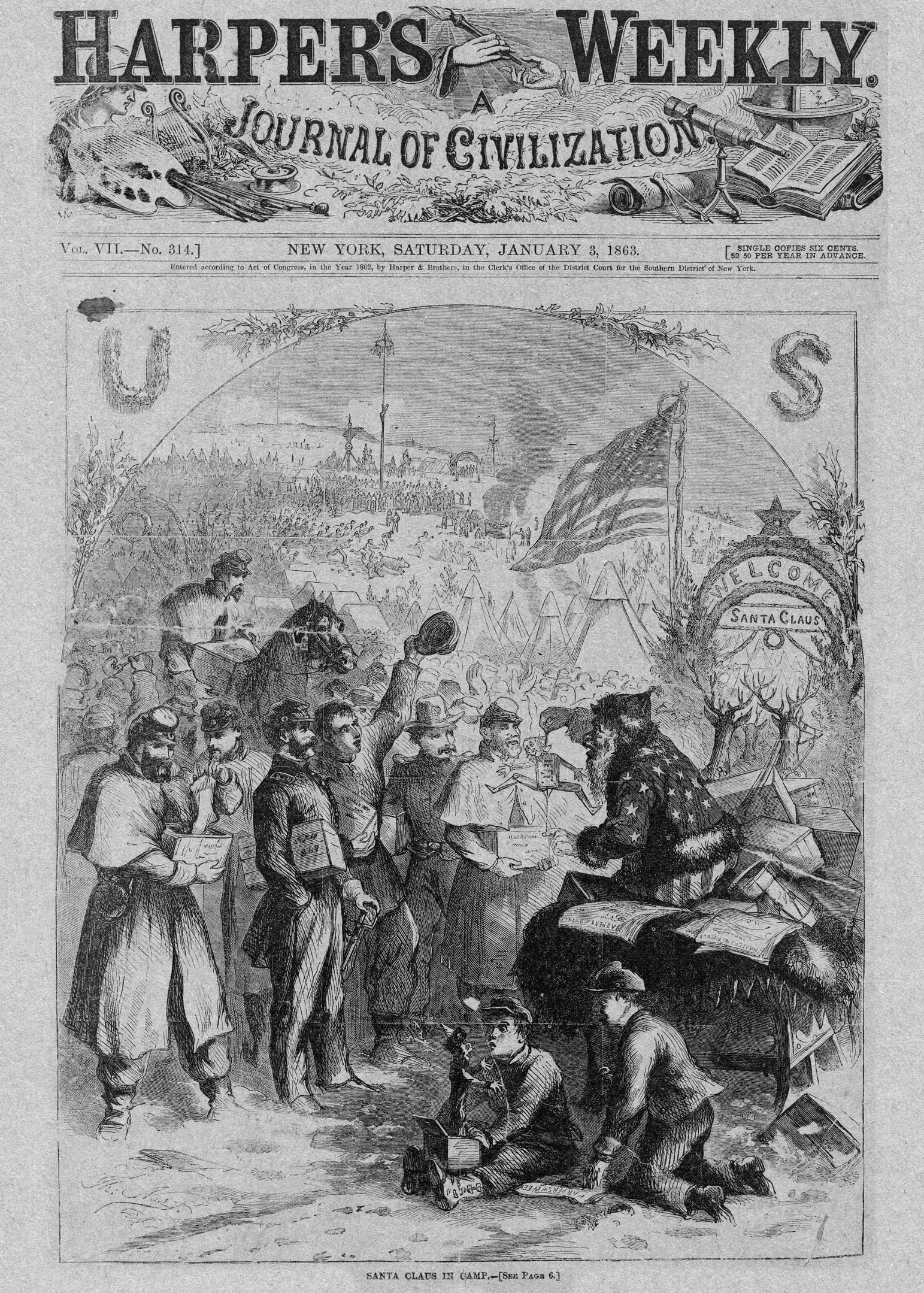

Indeed, in journals like Harper’s Weekly, the artist Thomas Nast strove to capture Santa’s form and features. In this cover feature from 1861 you can make out the antlers of the reindeer, the sleigh freighted with presents, the bearded old man in the star-spangled cloak (this is ‘Civil War Santa’).

The modern Santa Claus is best viewed as a blend of many rich and resonant things. Among them, it contains a great deal of Saint Nicholas; something of Charles Dickens; a fair amount of Thomas Nast’s imagination; and of course, a hint of Old Father Christmas •

All the black and white Public Domain photographs in this Viewfinder gallery have been meticulously restored from a high resolution digital scan from their original source. Share and use these remastered high resolution black & white historical pictures, for free, with Unsplash.

This Viewfinder gallery was originally published December 21, 2021.

References

Newspapers consulted: Bristol Observer, 22 December 1877. Coleraine Chronicle, 25 December 1886. Luton Times and Advertiser, 18 December 1885. The Sketch, 29 December 1897

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store