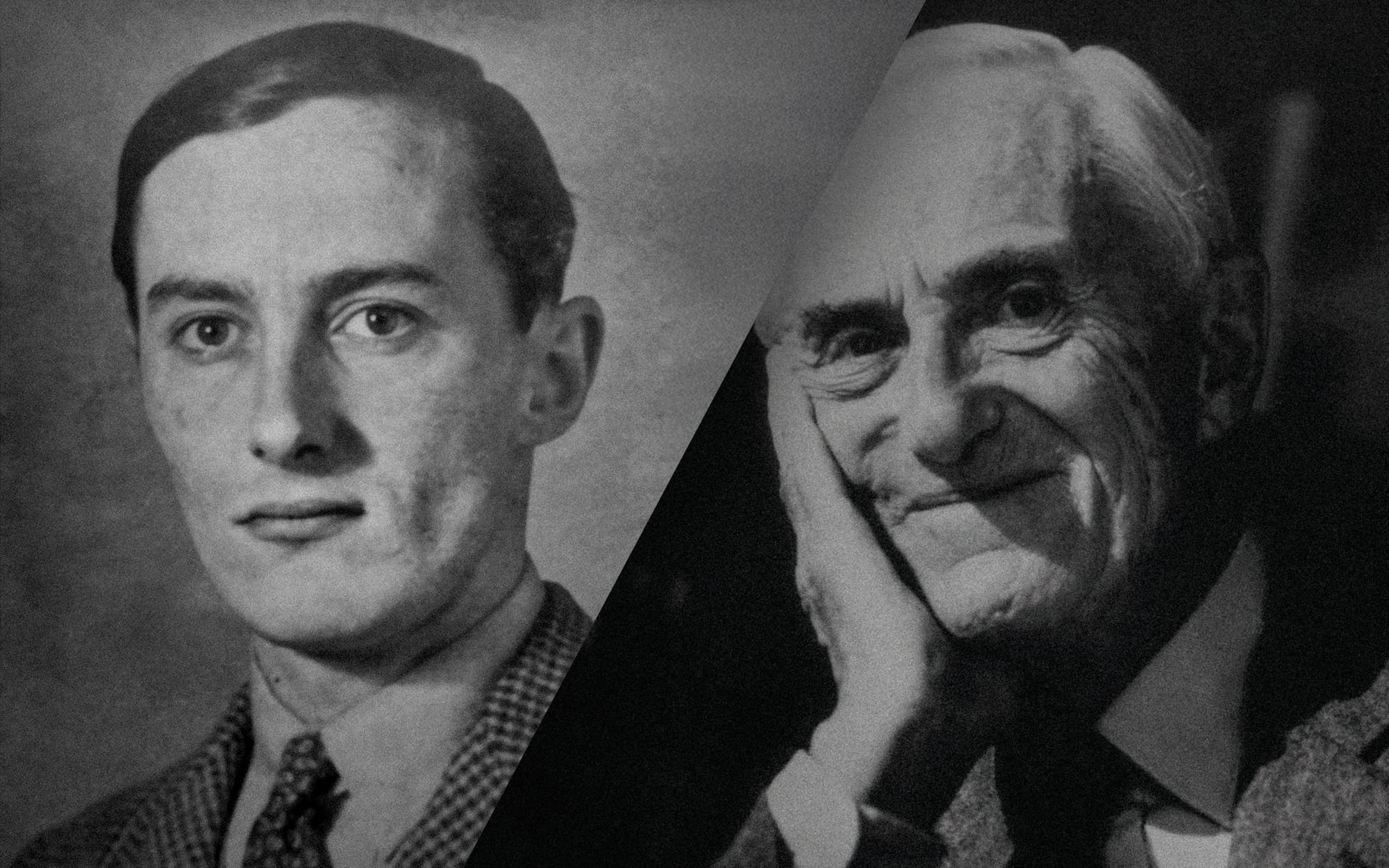

A Very Private Life – Nikolai Tolstoy Remembers Patrick O’Brian

We look back at the life of the 'greatest historical novelist of all time'

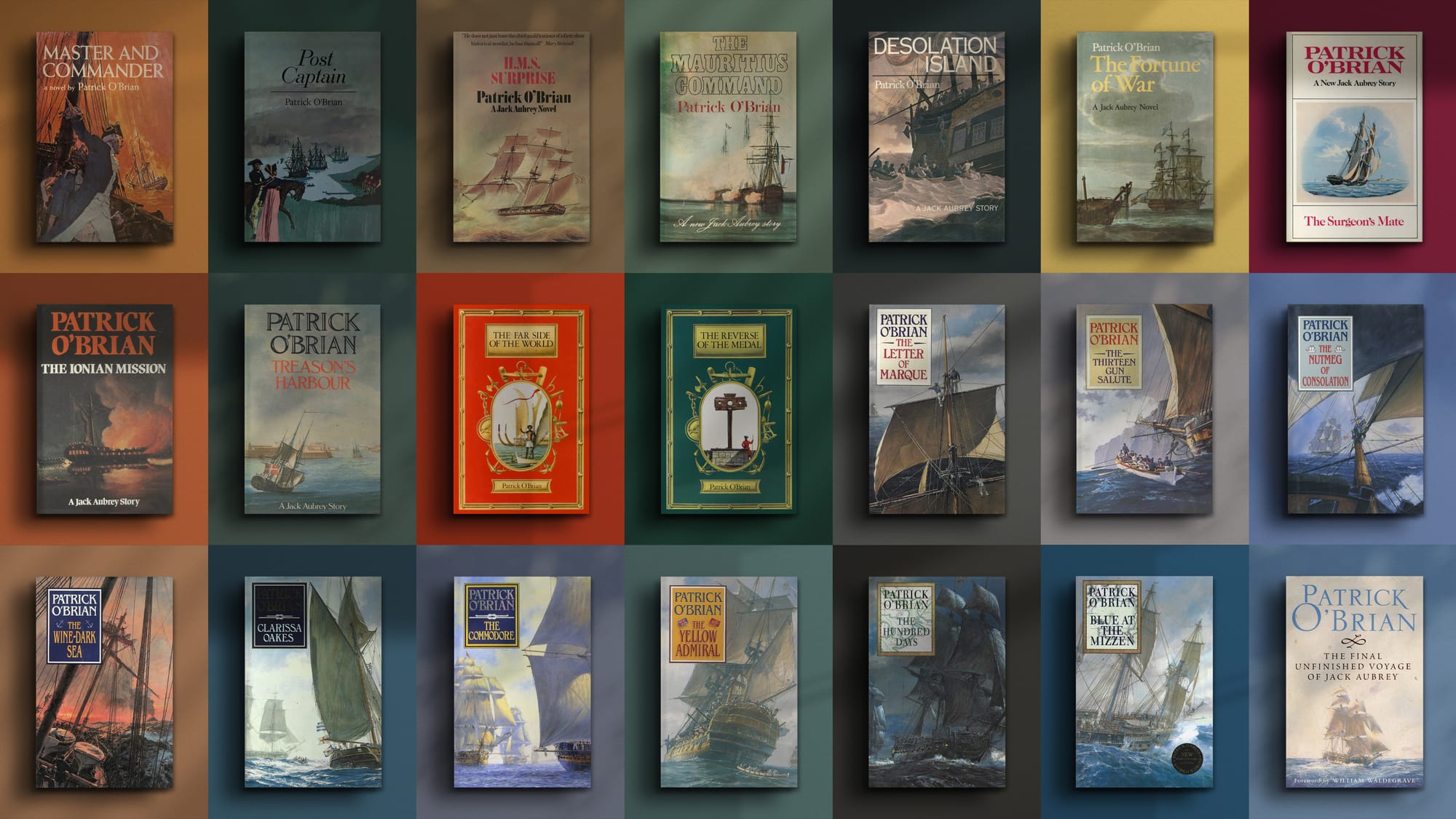

In the last decade of his life the author Patrick O'Brian (1914 - 2000) achieved global fame. His Aubrey-Maturin series of novels sold in the millions, Hollywood production studios battled for the film rights and O'Brian himself undertook a succession of high profile author tours to the United States of America.

This success, however, was long in the coming. For many years before the moment when the Times declared him 'the greatest historical novelist of all time', O'Brian was an author with only a modest, loyal following. Of the man himself, even these readers knew very little.

A quarter of a century after O'Brian's death, we sat down with one of the tiny few who actually knew the author intimately. Nikolai Tolstoy, an author himself, is O'Brian's stepson.

In this interview he tells us about his relationship with O'Brian, about his generosity and good humour, and his concerns about the misrepresentation of the author's legacy.

Listen to the interview here:

Tolstoy and O'Brian

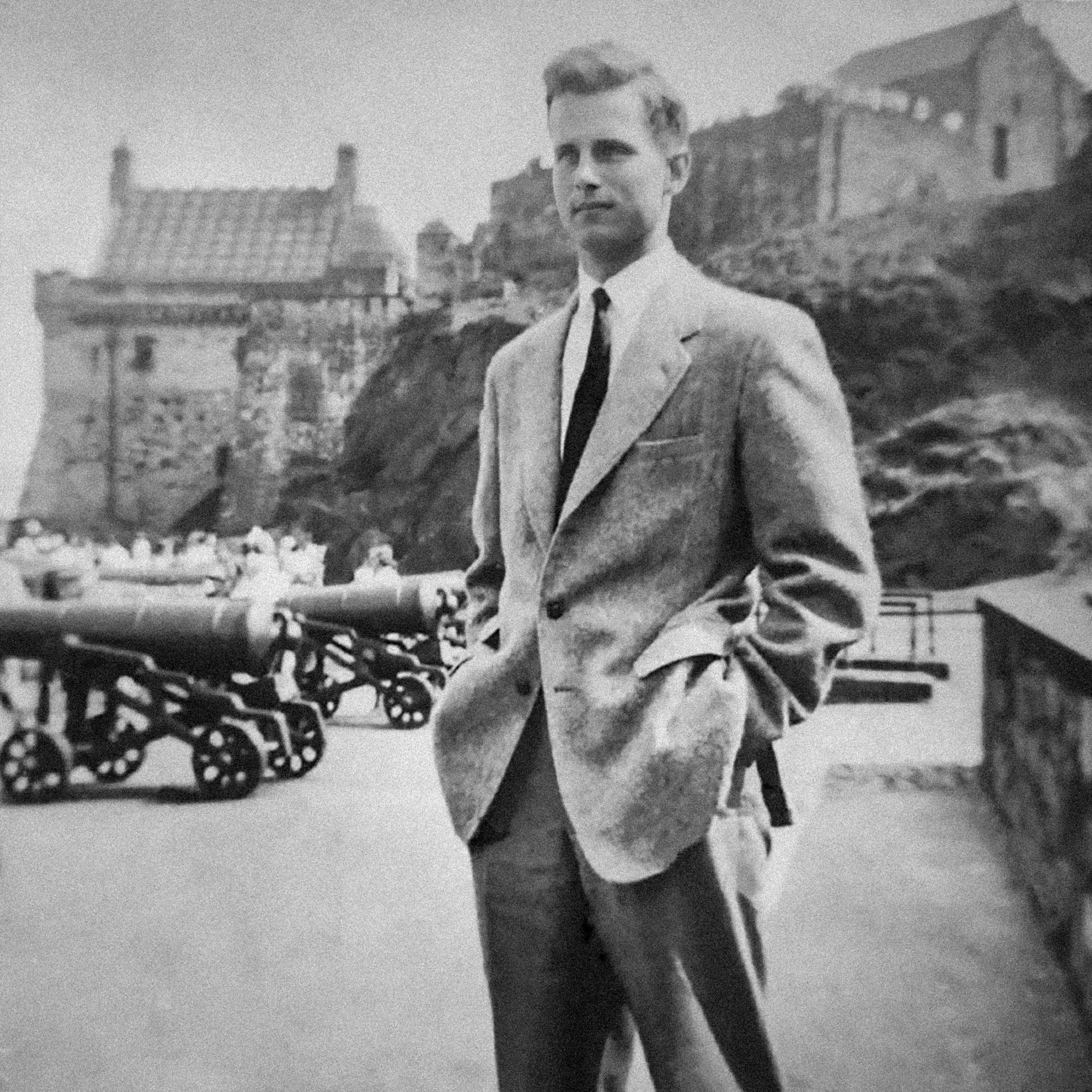

Nikolai Tolstoy can trace his relationship with Patrick O'Brian back with some precision to 1 September 1955. It was on that day, when Tolstoy was twenty and O'Brian was forty, that he walked up the rue Arago in Collioure, on the French Catalan coast, to the address where his mother and her new husband lived. He knocked on the door, 'and there was my mother', he later remembered, 'I vividly recall Patrick standing a little behind in that characteristic attitude which was to become so familiar, smiling with his head a little on one side and hands clasped before him'.

Even before the door opened, Tolstoy knew the significance of this moment. In his twenty years he had barely spent any time at all with Mary, his birth mother.

Meeting her for the first time was one thing, but the dynamic was complicated further still by the presence of O'Brian. He was a quiet man. He was a writer and a talented linguist. But nothing was said of his early life and during the following weeks in the late summer of 1955, Tolstoy and O'Brian clashed. 'By the time I left', Tolstoy acknowledges, 'a coldness had developed between us'.

It was an inauspicious beginning for what would grow into a close and confidential relationship. Over the decades that followed Tolstoy would see O'Brian establish a reputation first as a translator, then as a brilliant novelist and finally as a literary great.

In the last few years of his life, after Mary's death, O'Brian came to rely on Tolstoy completely.

Almost seventy years after he met O'Brian in Collioure, Tolstoy continues to live and write at a beautiful seventeenth-century property near Oxford. In the intervening years Tolstoy has published a great range of books, from The Quest for Merlin to a biography of Lord Camelford, The Half Mad Lord, as well as historical investigations into his own family history and events connected with World War Two.

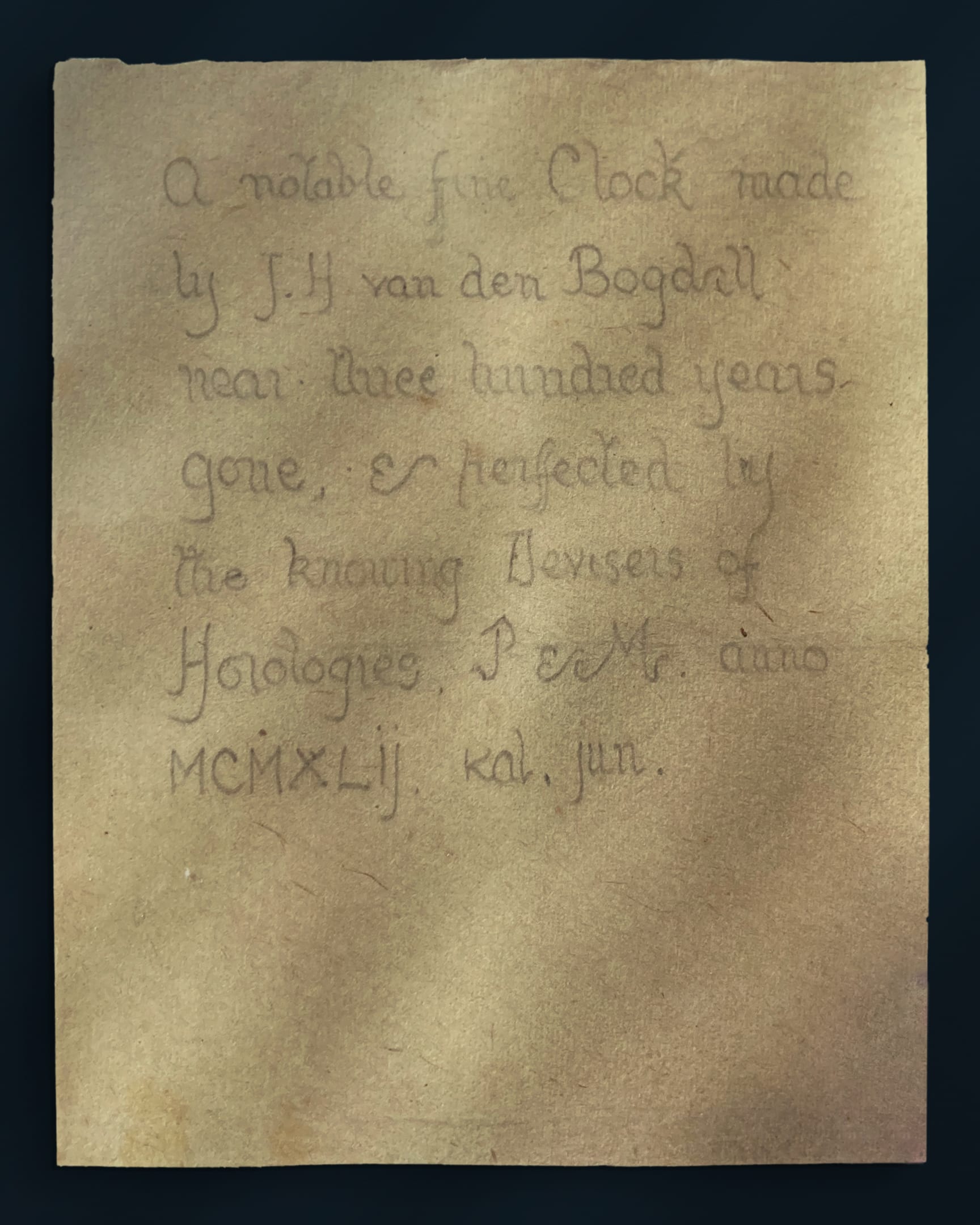

Many of these books were written in Tolstoy's beautiful library. This library - a long, narrow stone building, crammed from floor to ceiling with works on all imaginable topics - includes many of Patrick O'Brian's old books. These were bequeathed to Tolstoy by the author and they include many original eighteenth century editions of authors like Johnson, Swift and Boswell as well as the full set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and William Falkner's An Universal Dictionary of the Marine.

Also in the library, dotted here and there, are objects connected to O'Brian. There is a Noah's Ark he made for his grandchildren, his hat and briefcase, a device for determining latitude, a pair of 'Stephen Maturin's pincers', a fowling piece and many other things besides.

It was in this library, too, in the years after O'Brian's death in 2000 that quite unexpectedly Tolstoy found himself beginning a biographical project about his stepfather.

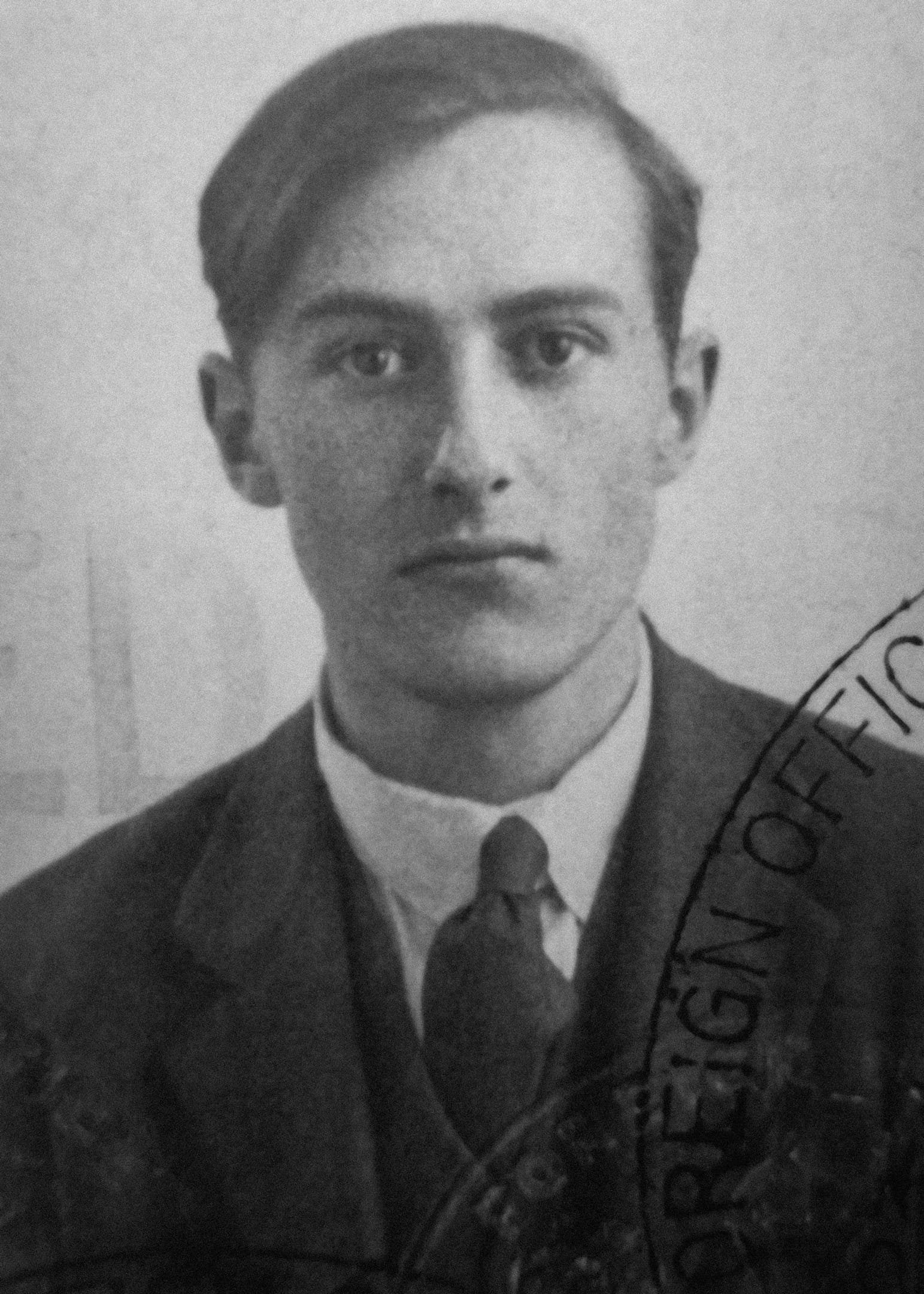

Patrick O'Brian was born in 1914 in a small village in southern Buckinghamshire. Throughout his life he kept details of his early life to himself, including the central fact that his first surname was 'Russ' and not 'O'Brian'. In the 1990s, at the time of his literary celebrity, it was generally believed that he came from an obscure part of Ireland and that he had spent his youth at sea.

O'Brian's change of identity was discovered in the last years of his life by an American author named Dean King. King produced the first biography, Patrick O'Brian: A Life Revealed, which was published shortly after the novelist's death. It was clear from talking to Tolstoy that the pain caused by this episode still lingers.

The questions generated by the affair are interesting ones. What right does a public figure have to a private life? What expectations should be placed on the authors of creative works?

For Tolstoy the consequences of King's biography were profound. He saw O'Brian become a paranoid, restless character as he was 'pursued' by the biographer. The presentation of O'Brian also affected his posthumous reputation.

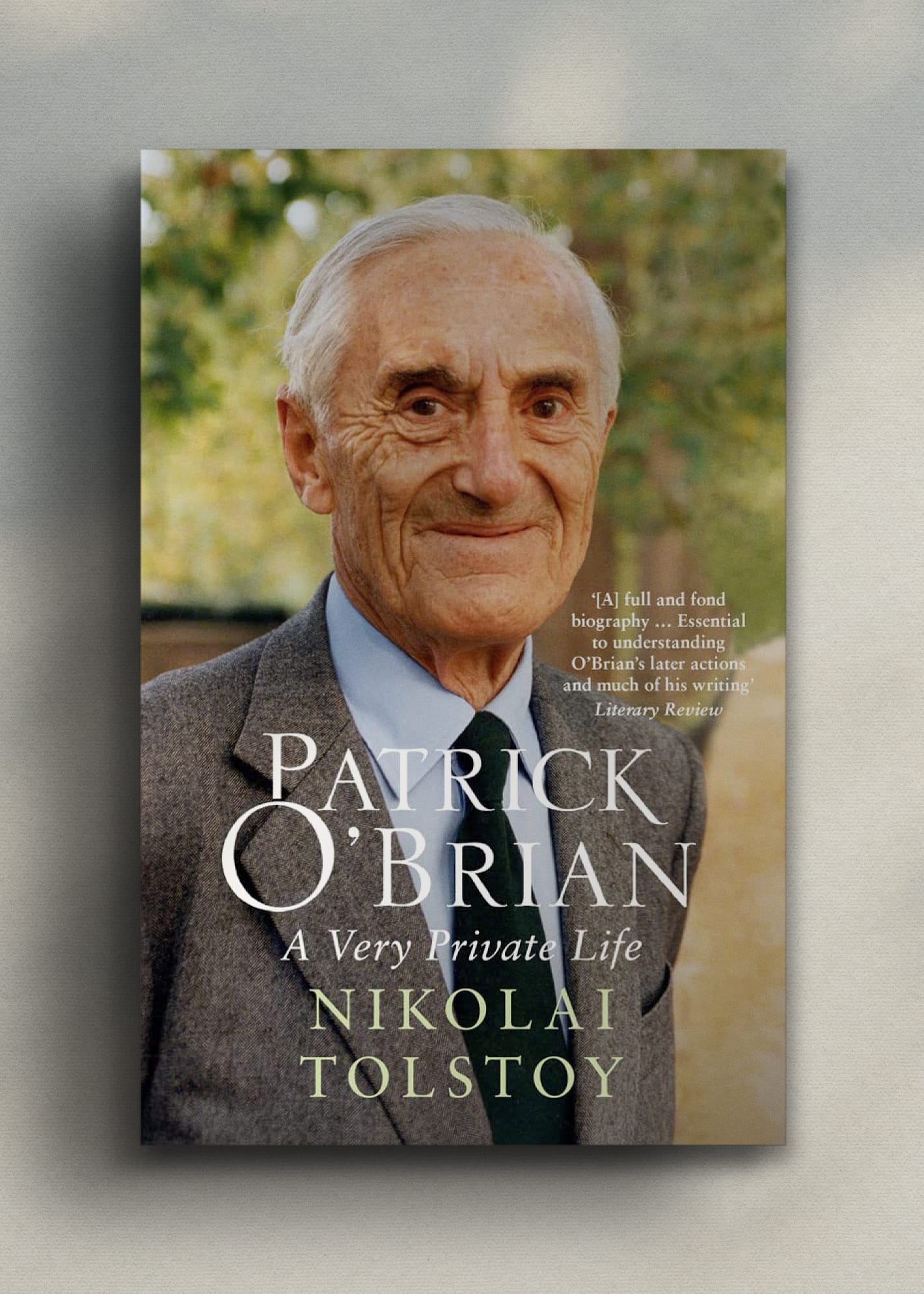

In consequence, he felt compelled to write a biography of his own in response to King's. Tolstoy's work was published in two volumes: Patrick O`Brian – The Making of the Novelist, 1914–1949 (2004) and A Very Private Life (2019).

The sad irony of this affair, is that while O'Brian worried intensely that he was going to be exposed as some kind of fraud, many of his readers cared very little about the personal aspects of his life.

To many he is, quite simply, a brilliant storyteller, a prose stylist and an author who can balance the technical challenges of describing life on a ship at sea, with the emotional demands of evoking the complex nature of human relationships. Of this last, O'Brian was a master. He might have described the Aubrey-Maturin novels as 'sea stories' but really they are one long chronicle of a friendship.

There are more aspects to O'Brian's writing too. One of them is his deep interests in nature. There is a passage, early on in the novel HMS Surprise, which captures both the elegance of O'Brian's prose and his affinity with the natural world.

'In Whitehall, a grey drizzle wept down upon the Admiralty, but in Sussex the air was dry - dry and perfectly still. The smoke rose from a chimney of the small drawing-room at Mapes Court in a tall, unwavering plume, a hundred feet before its head drifted away in a blue mist to lie in the hollows of the downs behind the house.

The leaves were hanging yet, but only just, and from time to time, the bright yellow rounds on the tree outside the window dropped of themselves, twirling in their low fall to join the golden carpet at its foot and in the silence, the whispering impact of each leaf could be heard – a silence as peaceful as an easy death.'

(Patrick O'Brian, HMS Surprise)

The years in which he was writing the Aubrey Maturin novels were years when Tolstoy saw O'Brian frequently. Each summer Tolstoy would spend several weeks in Collioure with his mother and step-father visiting the beach and cafes, playing tennis in the sunshine and enjoying conversation about history and politics.

Tolstoy had learned from his first visit that O'Brian could be a testy character. He was rigid in his work habits and disliked them being disturbed. But once these boundaries were understood, he relaxed into a far more benign and generous character who enjoyed good conversation, good wine and good books. Along with his writing, there was always some practical project underway.

Over the years Tolstoy came to appreciate O'Brian's peculiarities: his habit of making notes, lists and sketches and his eagerness to tackle all construction jobs, however hazardous, himself.

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of his parents' life was their propensity for embroiling themselves in car accidents. For years they would tour the mountain roads around their house in an aged Citroën 2CV, frequently coming to grief in incidents that were 'always somebody else's fault'.

During his visits Tolstoy was also able to observe Patrick and Mary's marriage at first hand. Mary O'Brian, Tolstoy reflects, was not a very intellectual person, nor was she particularly well read, but it became clear to Tolstoy she play a part of fundamental importance in O'Brian's literary process.

Mary was O'Brian's first reader and his great encourager. She had an instinct for critical judgment and once all of the creative work was done she typed the handwritten manuscript for the publisher.

As the couple's fortunes improved as the years passed, there was increased possibilities for hobbies and home improvements. O'Brian enjoyed making wine and any work in which he could use his hands. One of the playful productions from the mid-1970s is the Noah's Ark that was made in the happy intervals between chapters.

Music was another passion that became interwoven with the books. The O'Brian's would listen to a French classical music station, often taping music from their favourite composers. Among these the work of Boccherini, Mozart and Hadyn and the effect of this can be found in the novels, which open with a musical concert in Port Mahon.

Thereafter a love of music is the point in which Aubrey and Maturin's contrasting personalities meet throughout the novels. Often they are to be found at sea, gazing out of the stern windows of a frigate, lost to the world in the beauty of their piece.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s the Aubrey Maturin novels continued to come. They were always admired by those in high literary circles. A.S. Byatt and Iris Murdoch were among the committed fans. But it was not until January 1991 and the publication of an article by Richard Snow in the New York Times that O'Brian reached a mass audience. In that piece, An Author I'd Walk the Plank For, Snow admitted in delight, 'I might have been reading the prose of Jane Austen's seafaring brothers'.

From this moment onwards, O'Brian entered the ranks of the bestsellers. And with such a mass of work - short stories, novellas, literary novels - behind him, all of them little known, there was a great body of his writing for readers to explore. Having arrived in Collioure at mid-century with no money and no profile, O'Brian neared the end of the millennium as a wealthy public figure.

A strange fact, however, remained. While everyone seemingly 'knew' O'Brian, actually very few people did at all. As his editors and publicists had long known, he preferred to remain obscure, to answer 'no personal questions' and be known exclusively through his books. As his fame spread this desire became ever more difficult to reconcile with reality.

Watching all this was one of perhaps only a handful of people who did know O'Brian intimately. Tolstoy was by now a national figure himself, a writer and an historian who was active politically and as a campaigner.

In this conversation, published exactly a quarter of a century after O'Brian's death, Tolstoy goes back to the very beginning and that very first meeting in Collioure.

From there he roams through the poverty and the fame, the eccentricities, the brilliance and the paranoia, as he presents his own very personal portrait of one of our greatest historical novelists •

Nikolai Tolstoy is an English-Russian author and Patrick O’Brian’s step-son, their relationship spanned forty-five years during O’Brian’s marriage to Mary Tolstoy, Nikolai's mother. He has written a number of books, including Patrick O’Brian – The Making of a Novelist, The Coming of the King and Victims of Yalta. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1979.

Peter Moore is an English historian and writer. He is the author of the Sunday Times bestsellers The Weather Experiment and Endeavour. His latest book was a British pre-history of the American Revolution, Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness (2023). He teaches creative writing at the University of Oxford and edits the website Unseen Histories.

Patrick O'Brian: A Very Private Life

William Collins, 17 October, 2019

608 pages | ISBN: 978-0008350581

"One of the most gripping literary biographies of recent years"

– Sunday Times Culture

An intimate portrait of Patrick O’Brian, written by his stepson Nikolai Tolstoy. Patrick O’Brian was one of the greatest British novelists of the twentieth century, securing his place in literary history with the bestselling Aubrey–Maturin series, books that have sold millions of copies worldwide and been hailed as the best historical fiction of all time.

An exquisite novelist, translator and biographer, O’Brian moved in 1949 to Collioure in the south of France, where he led a secluded life with his wife Mary and wrote all his major works. The twenty books that make up the beloved Aubrey–Maturin series earned O’Brian the epithet ‘Jane Austen at sea’ for their authentic depiction of Nelson’s navy, and the relationship between Captain Jack Aubrey and his friend and ship’s surgeon Stephen Maturin. Outside his triumphant popularity in fiction, O’Brian also wrote erudite biographies of both Pablo Picasso and Joseph Banks, as well as publishing translations of Simone de Beauvoir and Henri Charrière.

In A Very Private Life, Nikolai Tolstoy draws upon his close relationship with his stepfather, as well as his notebooks, letters and photographs, to capture a highly researched but intimate account of those fifty years in Collioure that were the richest of O’Brian’s writing life. With warm and honest reflection, this biography gives insight into the genius of the little-known man behind the much-loved writing. Tolstoy also tells how, through a sad irony, unjust attacks on O’Brian’s private life destroyed much of the happiness he had gained from his achievement just as his literary career attained greater acclaim.

"Admirers of O'Brian's work will regard it as required reading"

– The Guardian

"Reading Tolstoy is like reading a fine, detailed detective story … To be treasured because it exposes and rebuts much falseness that has been written about O'Brian"

– Rachel Seiffert

With thanks to Nikolai Tolstoy. Music Adele Etheridge Woodson

Transcription

An illustrated transcript of this very special interview is available to members of the Unseen Histories' Club.