A Very Private Life – Nikolai Tolstoy Remembers Patrick O’Brian

We look back at the life of the 'greatest historical novelist of all time'

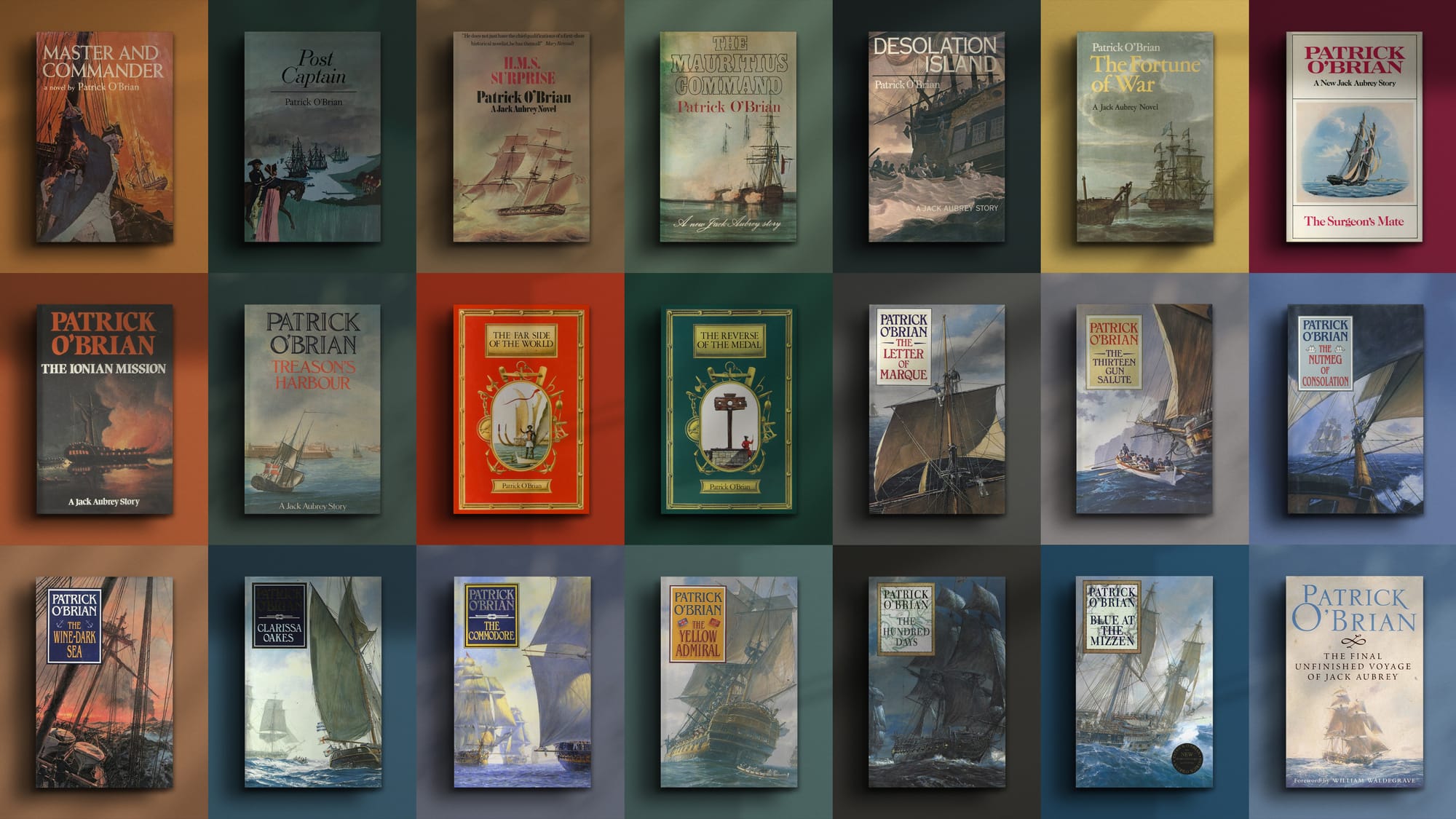

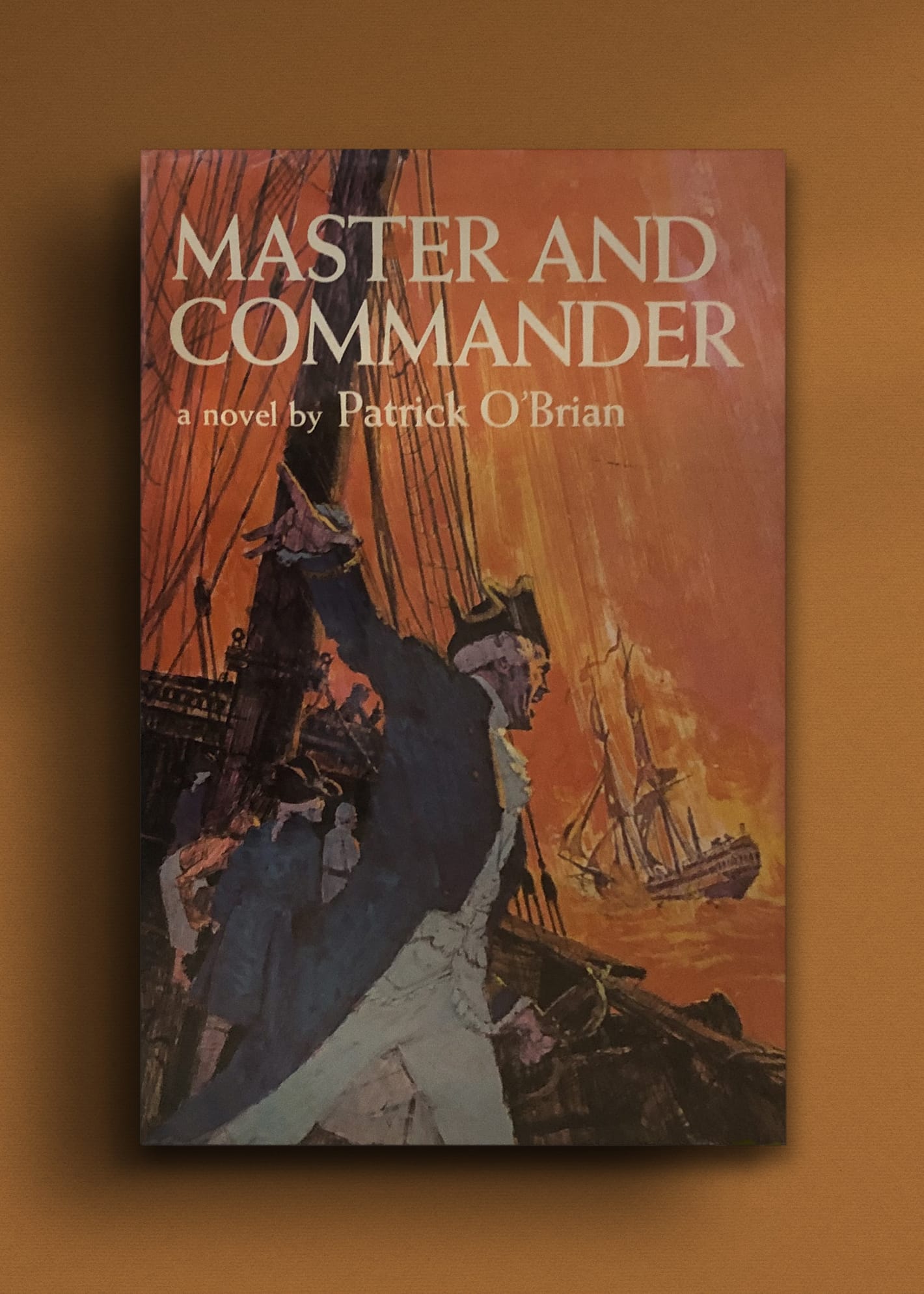

In the last decade of his life the author Patrick O'Brian (1914 - 2000) achieved global fame. His Aubrey-Maturin series of novels sold in the millions, Hollywood production studios battled for the film rights and O'Brian himself undertook a succession of high profile author tours to the United States of America.

This success, however, was long in the coming. For many years before the moment when the Times declared him 'the greatest historical novelist of all time', O'Brian was an author with only a modest, loyal following. Of the man himself, even these readers knew very little.

A quarter of a century after O'Brian's death, we sat down with one of the tiny few who actually knew the author intimately. Nikolai Tolstoy, an author himself, is O'Brian's stepson.

In this exclusive interview with Peter Moore, he tells us about his relationship with O'Brian, about his generosity and good humour, and his concerns about the misrepresentation of the author's legacy.

Interview by Peter Moore

Listen

This audio recording is 55:33 minutes.

Tolstoy and O'Brian

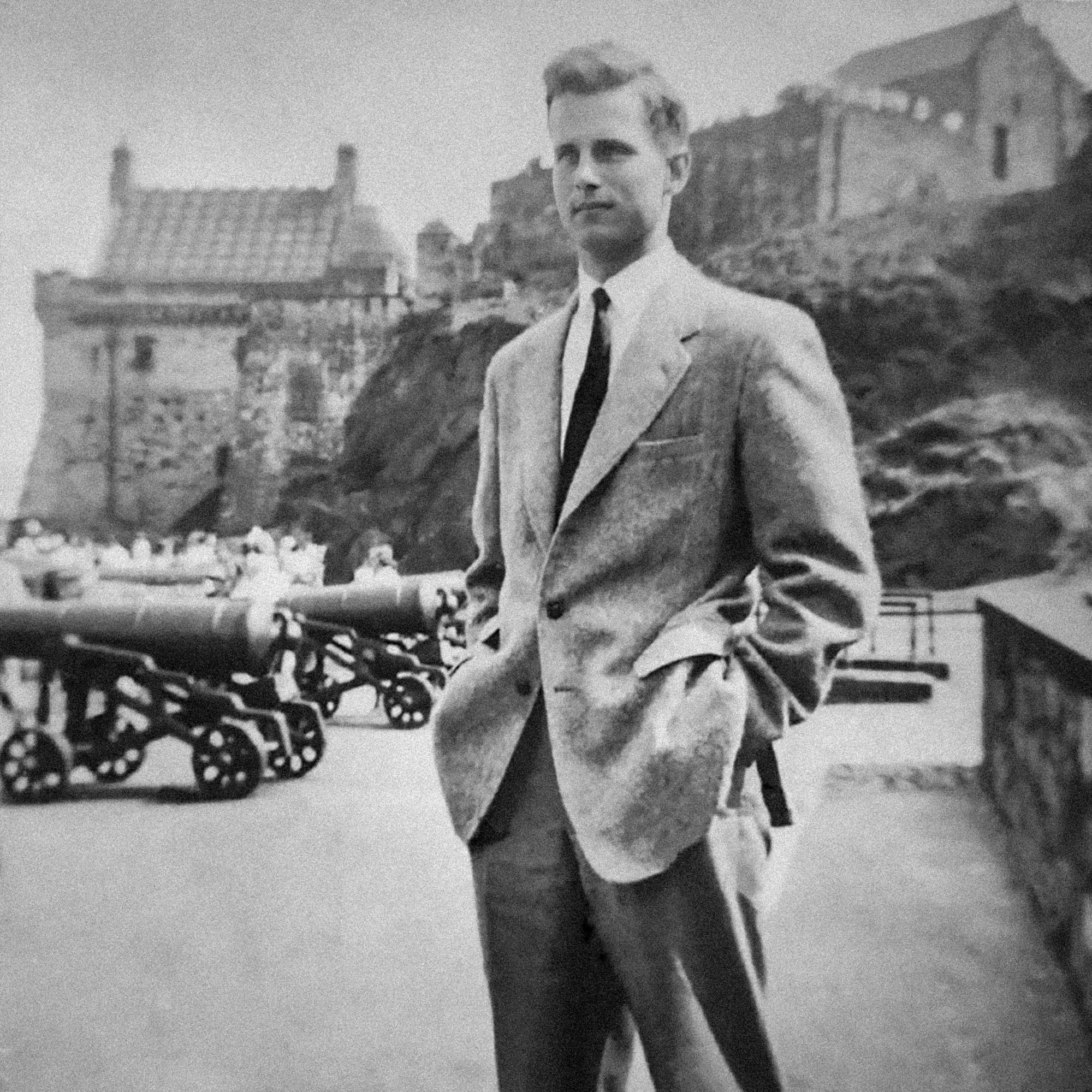

Nikolai Tolstoy can trace his relationship with Patrick O'Brian back with some precision to 1 September 1955. It was on that day, when Tolstoy was twenty and O'Brian was forty, that he walked up the rue Arago in Collioure, on the French Catalan coast, to the address where his mother and her new husband lived. He knocked on the door, 'and there was my mother', he later remembered, 'I vividly recall Patrick standing a little behind in that characteristic attitude which was to become so familiar, smiling with his head a little on one side and hands clasped before him'.

Even before the door opened, Tolstoy knew the significance of this moment. In his twenty years he had barely spent any time at all with Mary, his birth mother.

Meeting her for the first time was one thing, but the dynamic was complicated further still by the presence of O'Brian. He was a quiet man. He was a writer and a talented linguist. But nothing was said of his early life and during the following weeks in the late summer of 1955, Tolstoy and O'Brian clashed. 'By the time I left', Tolstoy acknowledges, 'a coldness had developed between us'.

It was an inauspicious beginning for what would grow into a close and confidential relationship. Over the decades that followed Tolstoy would see O'Brian establish a reputation first as a translator, then as a brilliant novelist and finally as a literary great.

In the last few years of his life, after Mary's death, O'Brian came to rely on Tolstoy completely.

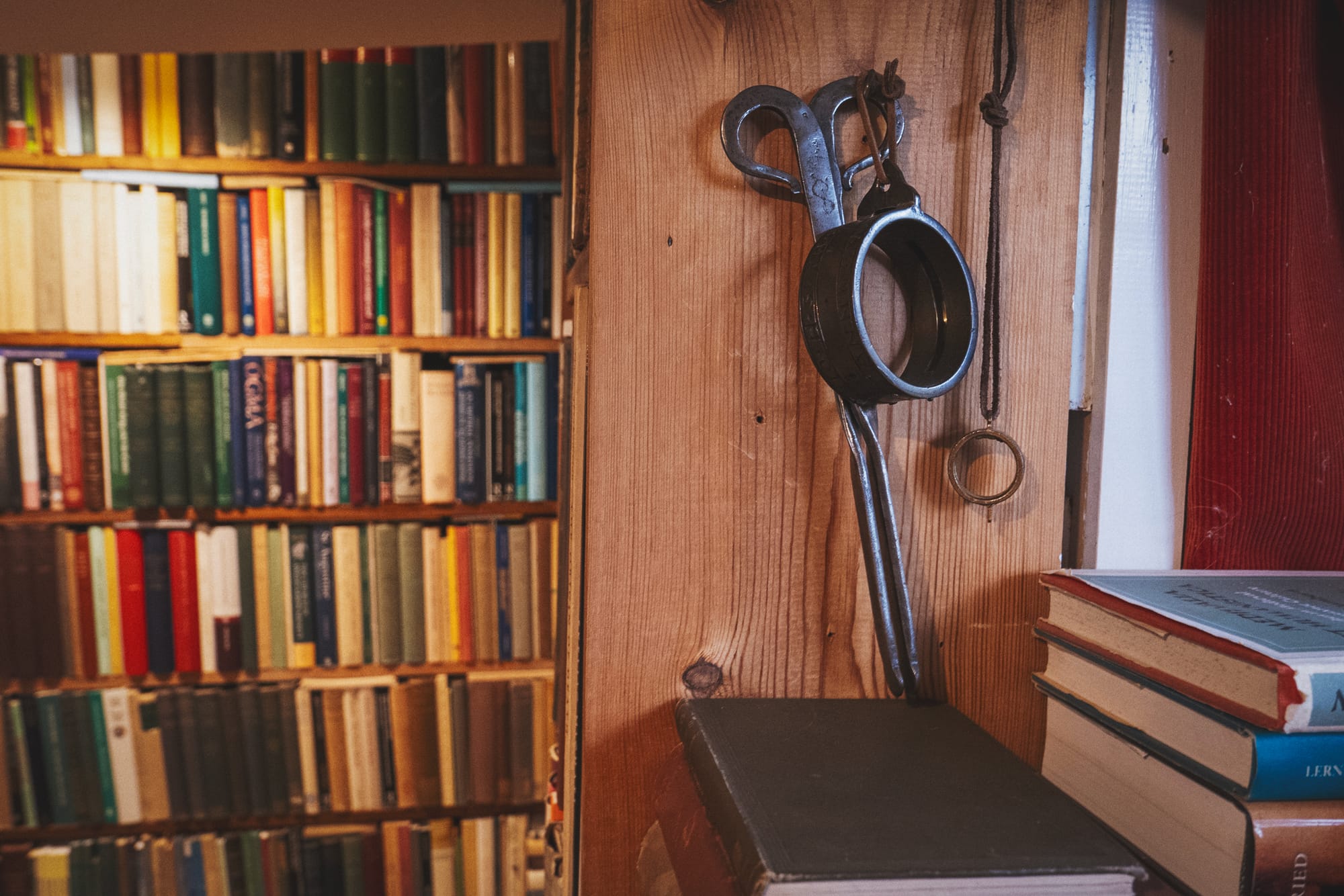

Almost seventy years after he met O'Brian in Collioure, Tolstoy continues to live and write at a beautiful seventeenth-century property near Oxford. In the intervening years Tolstoy has published a great range of books, from The Quest for Merlin to a biography of Lord Camelford, The Half Mad Lord, as well as historical investigations into his own family history and events connected with World War Two.

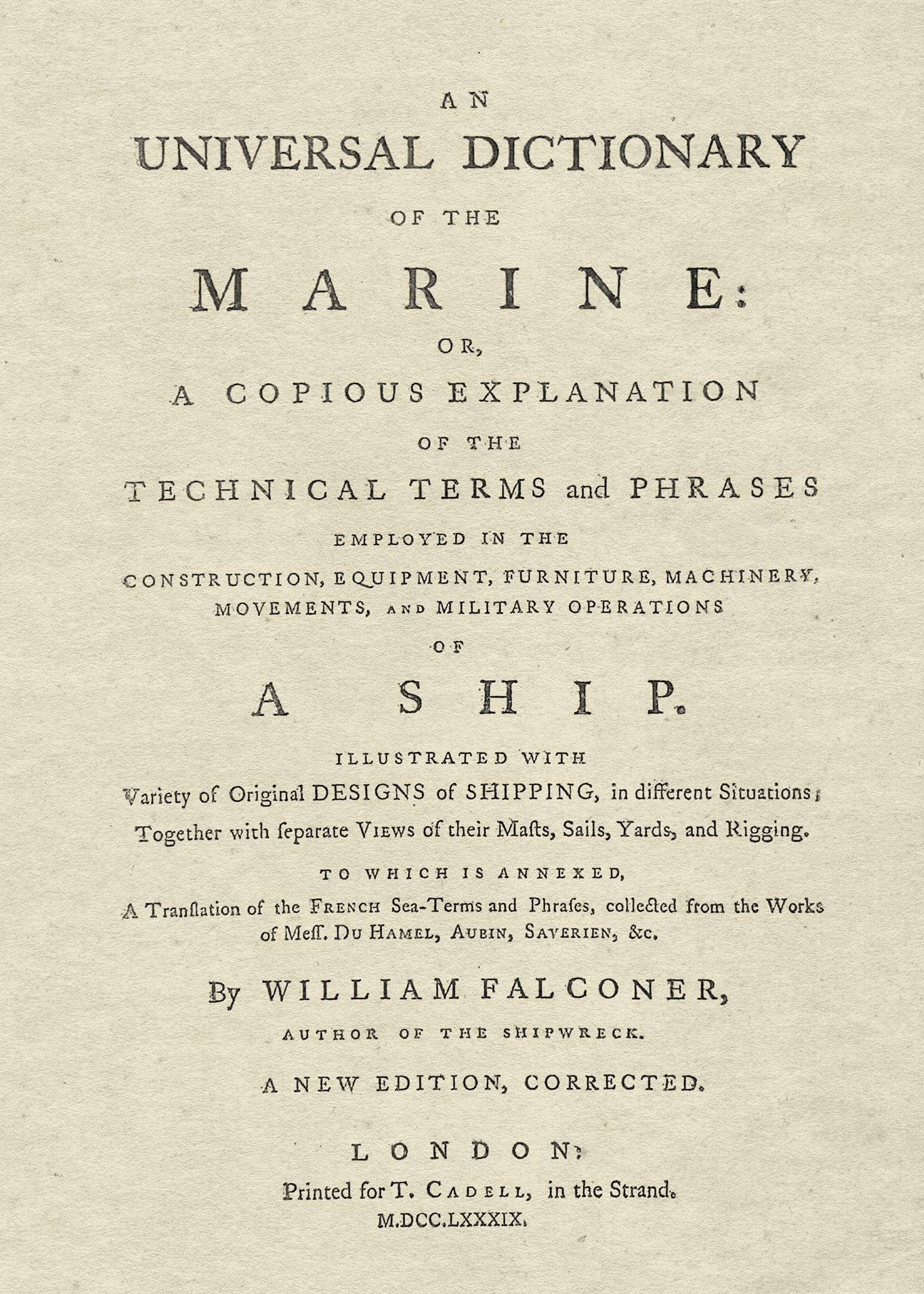

Many of these books were written in Tolstoy's beautiful library. This library - a long, narrow stone building, crammed from floor to ceiling with works on all imaginable topics - includes many of Patrick O'Brian's old books. These were bequeathed to Tolstoy by the author and they include many original eighteenth century editions of authors like Johnson, Swift and Boswell as well as the full set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and William Falkner's An Universal Dictionary of the Marine.

Also in the library, dotted here and there, are objects connected to O'Brian. There is a Noah's Ark he made for his grandchildren, his hat and briefcase, a device for determining latitude, a pair of 'Stephen Maturin's pincers', a fowling piece and many other things besides.

It was in this library, too, in the years after O'Brian's death in 2000 that quite unexpectedly Tolstoy found himself beginning a biographical project about his stepfather.

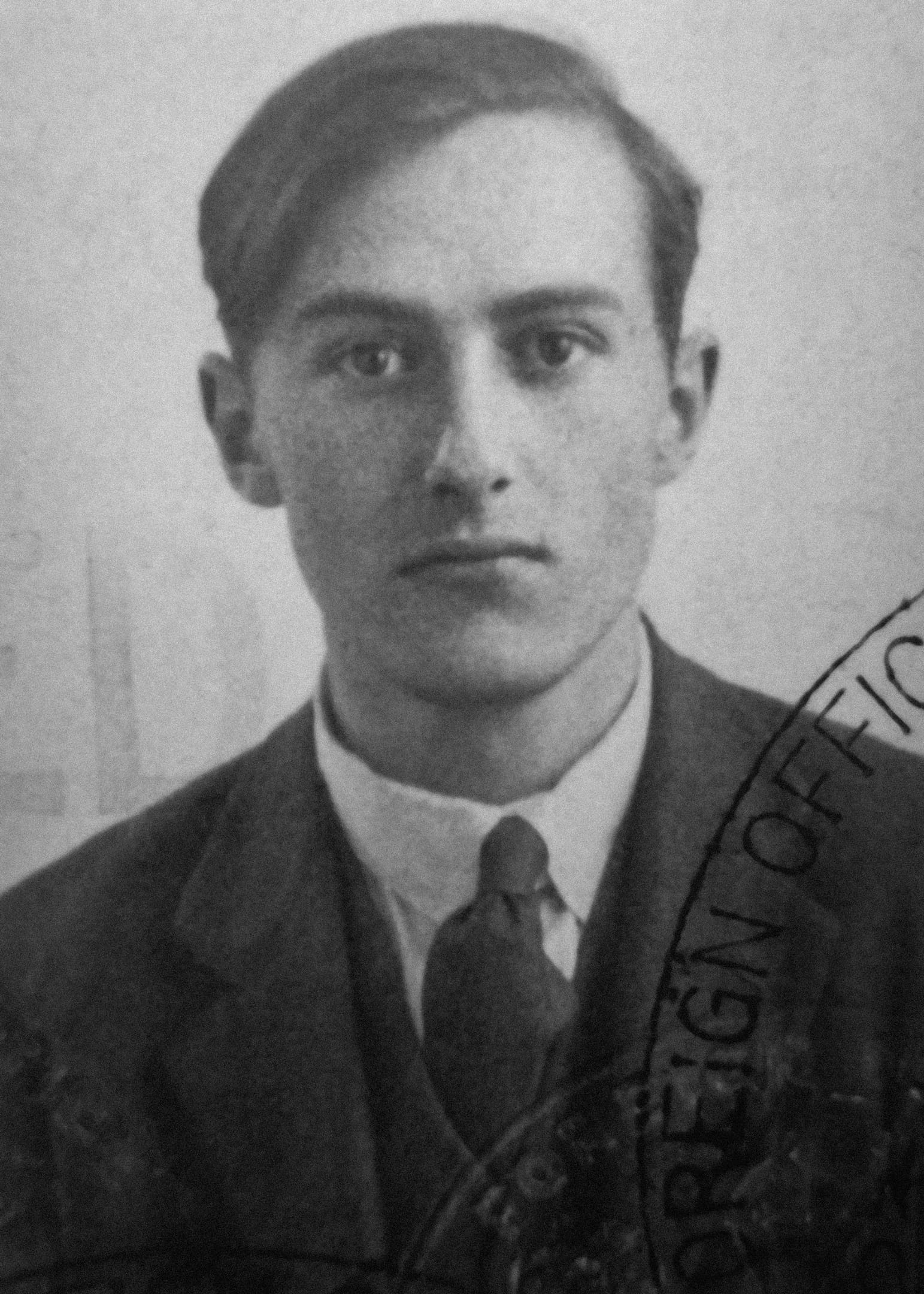

Patrick O'Brian was born in 1914 in a small village in southern Buckinghamshire. Throughout his life he kept details of his early life to himself, including the central fact that his first surname was 'Russ' and not 'O'Brian'. In the 1990s, at the time of his literary celebrity, it was generally believed that he came from an obscure part of Ireland and that he had spent his youth at sea.

O'Brian's change of identity was discovered in the last years of his life by an American author named Dean King. King produced the first biography, Patrick O'Brian: A Life Revealed, which was published shortly after the novelist's death. It was clear from talking to Tolstoy that the pain caused by this episode still lingers.

The questions generated by the affair are interesting ones. What right does a public figure have to a private life? What expectations should be placed on the authors of creative works?

For Tolstoy the consequences of King's biography were profound. He saw O'Brian become a paranoid, restless character as he was 'pursued' by the biographer. The presentation of O'Brian also affected his posthumous reputation.

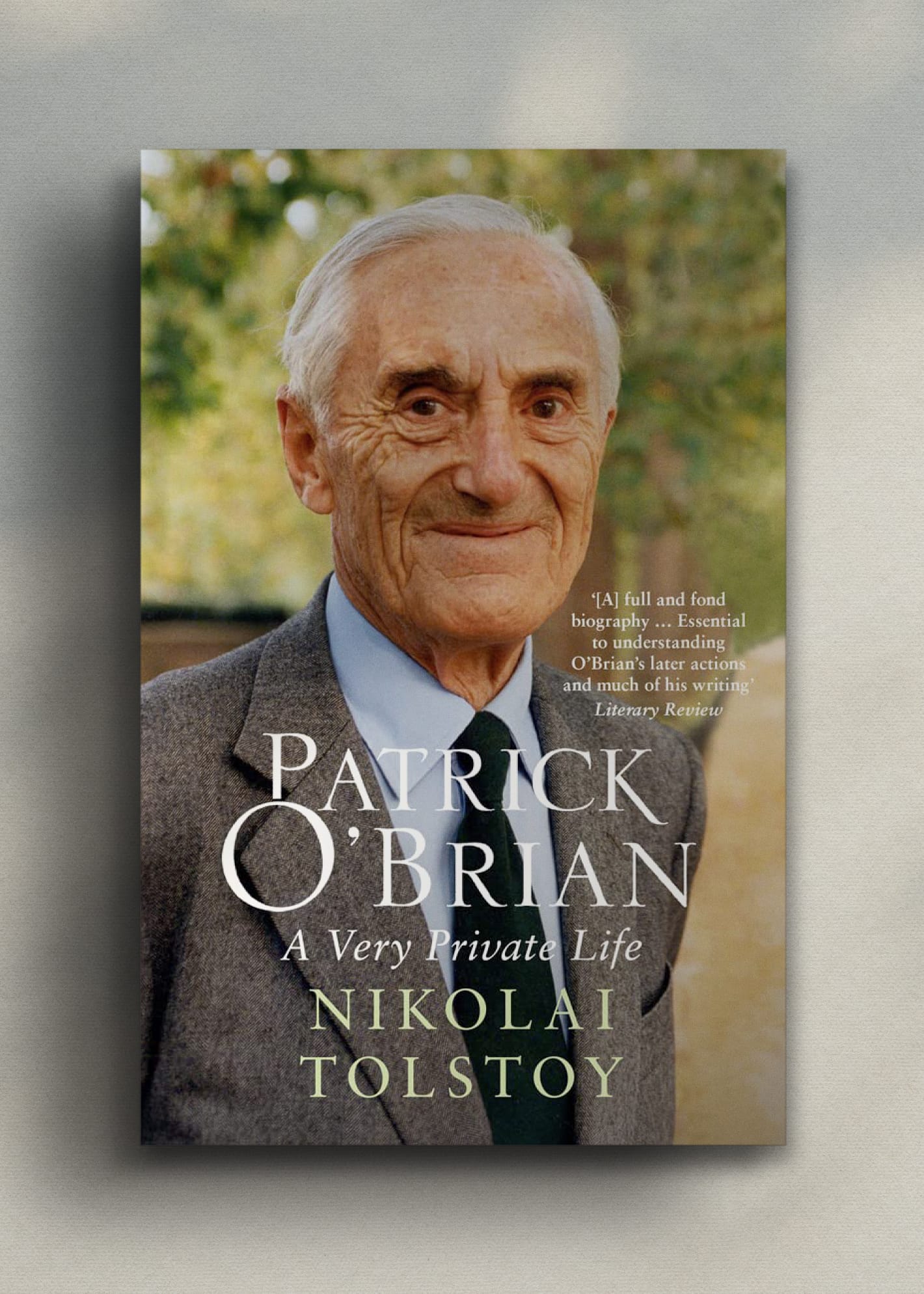

In consequence, he felt compelled to write a biography of his own in response to King's. Tolstoy's work was published in two volumes: Patrick O`Brian – The Making of the Novelist, 1914–1949 (2004) and A Very Private Life (2019).

The sad irony of this affair, is that while O'Brian worried intensely that he was going to be exposed as some kind of fraud, many of his readers cared very little about the personal aspects of his life.

To many he is, quite simply, a brilliant storyteller, a prose stylist and an author who can balance the technical challenges of describing life on a ship at sea, with the emotional demands of evoking the complex nature of human relationships. Of this last, O'Brian was a master. He might have described the Aubrey-Maturin novels as 'sea stories' but really they are one long chronicle of a friendship.

There are more aspects to O'Brian's writing too. One of them is his deep interests in nature. There is a passage, early on in the novel HMS Surprise, which captures both the elegance of O'Brian's prose and his affinity with the natural world.

‘In Whitehall, a grey drizzle wept down upon the Admiralty, but in Sussex the air was dry - dry and perfectly still. The smoke rose from a chimney of the small drawing-room at Mapes Court in a tall, unwavering plume, a hundred feet before its head drifted away in a blue mist to lie in the hollows of the downs behind the house.

The leaves were hanging yet, but only just, and from time to time, the bright yellow rounds on the tree outside the window dropped of themselves, twirling in their low fall to join the golden carpet at its foot and in the silence, the whispering impact of each leaf could be heard – a silence as peaceful as an easy death.’

– Patrick O'Brian, HMS Surprise

The years in which he was writing the Aubrey Maturin novels were years when Tolstoy saw O'Brian frequently. Each summer Tolstoy would spend several weeks in Collioure with his mother and step-father visiting the beach and cafes, playing tennis in the sunshine and enjoying conversation about history and politics.

Tolstoy had learned from his first visit that O'Brian could be a testy character. He was rigid in his work habits and disliked them being disturbed. But once these boundaries were understood, he relaxed into a far more benign and generous character who enjoyed good conversation, good wine and good books. Along with his writing, there was always some practical project underway.

Over the years Tolstoy came to appreciate O'Brian's peculiarities: his habit of making notes, lists and sketches and his eagerness to tackle all construction jobs, however hazardous, himself.

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of his parents' life was their propensity for embroiling themselves in car accidents. For years they would tour the mountain roads around their house in an aged Citroën 2CV, frequently coming to grief in incidents that were 'always somebody else's fault'.

During his visits Tolstoy was also able to observe Patrick and Mary's marriage at first hand. Mary O'Brian, Tolstoy reflects, was not a very intellectual person, nor was she particularly well read, but it became clear to Tolstoy she play a part of fundamental importance in O'Brian's literary process.

Mary was O'Brian's first reader and his great encourager. She had an instinct for critical judgment and once all of the creative work was done she typed the handwritten manuscript for the publisher.

As the couple's fortunes improved as the years passed, there was increased possibilities for hobbies and home improvements. O'Brian enjoyed making wine and any work in which he could use his hands. One of the playful productions from the mid-1970s is the Noah's Ark that was made in the happy intervals between chapters.

Music was another passion that became interwoven with the books. The O'Brian's would listen to a French classical music station, often taping music from their favourite composers. Among these the work of Boccherini, Mozart and Hadyn and the effect of this can be found in the novels, which open with a musical concert in Port Mahon.

Thereafter a love of music is the point in which Aubrey and Maturin's contrasting personalities meet throughout the novels. Often they are to be found at sea, gazing out of the stern windows of a frigate, lost to the world in the beauty of their piece.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s the Aubrey Maturin novels continued to come. They were always admired by those in high literary circles. A.S. Byatt and Iris Murdoch were among the committed fans. But it was not until January 1991 and the publication of an article by Richard Snow in the New York Times that O'Brian reached a mass audience. In that piece, An Author I'd Walk the Plank For, Snow admitted in delight, 'I might have been reading the prose of Jane Austen's seafaring brothers'.

From this moment onwards, O'Brian entered the ranks of the bestsellers. And with such a mass of work - short stories, novellas, literary novels - behind him, all of them little known, there was a great body of his writing for readers to explore. Having arrived in Collioure at mid-century with no money and no profile, O'Brian neared the end of the millennium as a wealthy public figure.

A strange fact, however, remained. While everyone seemingly 'knew' O'Brian, actually very few people did at all. As his editors and publicists had long known, he preferred to remain obscure, to answer 'no personal questions' and be known exclusively through his books. As his fame spread this desire became ever more difficult to reconcile with reality.

Watching all this was one of perhaps only a handful of people who did know O'Brian intimately. Tolstoy was by now a national figure himself, a writer and an historian who was active politically and as a campaigner.

In this conversation, published exactly a quarter of a century after O'Brian's death, Tolstoy goes back to the very beginning and that very first meeting in Collioure.

From there he roams through the poverty and the fame, the eccentricities, the brilliance and the paranoia, as he presents his own very personal portrait of one of our greatest historical novelists •

This interview was originally published January 2, 2025.

Patrick O'Brian: A Very Private Life

William Collins, 17 October, 2019

608 pages | ISBN: 978-0008350581

“One of the most gripping literary biographies of recent years” – Sunday Times Culture

An intimate portrait of Patrick O’Brian, written by his stepson Nikolai Tolstoy. Patrick O’Brian was one of the greatest British novelists of the twentieth century, securing his place in literary history with the bestselling Aubrey–Maturin series, books that have sold millions of copies worldwide and been hailed as the best historical fiction of all time.

An exquisite novelist, translator and biographer, O’Brian moved in 1949 to Collioure in the south of France, where he led a secluded life with his wife Mary and wrote all his major works. The twenty books that make up the beloved Aubrey–Maturin series earned O’Brian the epithet ‘Jane Austen at sea’ for their authentic depiction of Nelson’s navy, and the relationship between Captain Jack Aubrey and his friend and ship’s surgeon Stephen Maturin. Outside his triumphant popularity in fiction, O’Brian also wrote erudite biographies of both Pablo Picasso and Joseph Banks, as well as publishing translations of Simone de Beauvoir and Henri Charrière.

In A Very Private Life, Nikolai Tolstoy draws upon his close relationship with his stepfather, as well as his notebooks, letters and photographs, to capture a highly researched but intimate account of those fifty years in Collioure that were the richest of O’Brian’s writing life. With warm and honest reflection, this biography gives insight into the genius of the little-known man behind the much-loved writing. Tolstoy also tells how, through a sad irony, unjust attacks on O’Brian’s private life destroyed much of the happiness he had gained from his achievement just as his literary career attained greater acclaim.

“Admirers of O'Brian's work will regard it as required reading”

― The Guardian

“Reading Tolstoy is like reading a fine, detailed detective story … To be treasured because it exposes and rebuts much falseness that has been written about O'Brian”

― Rachel Seiffert

With thanks to Nikolai Tolstoy. Audio Production by Maria Nolan, with music by Adele Etheridge Woodson.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store

An illustrated transcript of this very special interview is available to members of the Unseen Histories' Club.

Introduction

Hello, I’m Peter Moore, a writer and a historian. Here, we have something very special indeed for you on Unseen Histories. It’s a conversation about the author Patrick O’Brian; a writer who was called by The New York Times ‘the greatest historical novelist of all time’.

There are two things that many readers and lovers of history know about Patrick O’Brian; first of all, that he was the most magnificent writer. He’s most famous of all for his Aubrey-Maturin series of novels; ‘sea stories’ (as he called them) set in a period of the Napoleonic Wars. These evoke with the greatest ability that rich, expansive, textured world governed by class and form an ingenuity that is so transfixing for us to look back upon today. Even non-readers will have come across some of O’Brian’s story-telling through the 2003 feature film, Master and Commander.

The other thing people know about O’Brian is that he was a recluse. He lived his life determinedly out of the public gaze on the French Catalan coast. Only a tiny few actually knew him intimately, one of whom was his beloved wife, Mary, with whom he was inseparable. Another was his stepson, Mary’s child from her first marriage, Nikolai Tolstoy.

Nikolai is a distinguished author himself and he continues to write and live happily in a beautiful house near Oxford. There, he spends much of his time in a library that’s filled with books, many of which he inherited from his stepfather. It was in this room that I sat down for a chat with Nikolai about Patrick. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Peter Moore

Hello, Nikolai Tolstoy. This is a real pleasure. First of all, thank you very much for your time. We’re here in this most enchanting of spaces; one of my favourite places of all I have to say.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Oh, well thank you.

Peter Moore

We’re surrounded by hundreds or maybe, I guess, even thousands of books. Many of them once belonged to the novelist Patrick O’Brian and they were central to his work. Could I begin by asking you just to say a few words about your own life and if you could tell us how you’re connected to Patrick?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, I was connected to Patrick at a very early age and, indeed, I’ve got a photograph taken by my mother. The first time I ever heard of Patrick, he didn’t mean much to me because I was only aged five I think.

In the photograph, I’m sitting on the lawn, during the war, of my grandparent’s house in North Devon where we went for the evacuation. My mother was working in London with Patrick. She was not yet married to him but I’m not sure. Anyway, they were living in London and they were both driving ambulances in the Blitz in Chelsea. It was a very awkward place because it was where the Luftwaffe came up the Thames by moonlight, turned around at Battersea Power Station and any bombs they had left, they had to drop on Chelsea. One went smack on the house next door which I’ve got a picture of. Anyway, they survived.

My mother couldn’t come very often and so I’ve almost no childhood memories or about three fleeting ones of my mother. I do remember this and I think it must have been because she had some passion in her voice which I must have recognised.

She said, ‘I’ve got a friend and he’s an author.’ Patrick wasn’t a very successful author then but he had, as a child, published books. I didn’t really know what an author was and I must have asked my mother. She said, ‘It’s someone who writes books.’

When my mother went back to London, I decided I would be an author too. I took an exercise book and I wrote on the front the title which was called The Lions. Obviously, I liked research and things like that or thought I did at that age. I wrote the index and then I never got around to writing any more. Years later, when I first got to know Patrick, I told him about this and Patrick smiled and he said, ‘I think it’s the bit in between that counts usually.’ [Laughter]

Peter Moore

I think I should say at the beginning that when I suggested this idea of having a conversation about Patrick to some of his online fans, of which there are very many, one of them replied and said, ‘I would humbly suggest that we would like to hear about our author’s inspiration for his books, his research, his methods of writing but not his private life which is none of our business.’

This line obviously echoes Patrick’s own thinking because he was very famously very reclusive and very private. I had borne it in mind but I do actually think it’s fair to discuss what he called, very disparagingly, ‘personal questions’ [laughter] for two reasons.

First of all, Patrick I think is an immense figure in the history of English literature, not just in the 20th century but really his books transcend that. I think they’re of such great quality that we kind of deserve to know as much as we can because we’re curious about the person who created them.

Second of all, it has to be pointed out ... and I know that you’ve pointed this out yourself that Patrick did write biographies of Picasso and he wrote about Joseph Banks and he enquired into their personal lives because he saw how that was fundamental to the kind of people that they were. So I think we’re kind of justified in talking a little bit about the personal side of Patrick too.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Well, he was very ambivalent in my experience and I didn’t intend to write his biography because had I done so, I would have collected much more and taken notes which I hadn’t.

As you say, he didn’t like anything personal becoming known but when he died, this decision for me changed absolutely radically because a ludicrous biography came out by Dean King, an American enthusiast who never actually met Patrick or anyone because he told them he wouldn’t speak to anyone. He came here but I told him, ‘Patrick has asked me not to talk about him,’ so he got nothing out of me.

The book itself was naively reviewed by people almost unanimously saying ‘This is a breakthrough. Now we know the real Patrick.’ It was full of the most childish mistakes so I thought, ‘It can’t stay like that on the record.’ I think I must have discussed it with the publisher and so I decided to write his biography myself.

As I’d known him since I was 18, when I first met him, I knew him very well indeed. When I then did more research, I found just how wrong these things were. Patrick’s ambivalence is shown when he once wrote to me (I think I’ve still got the letter) and he said, ‘Nikolai, when I die, I want you to come straightaway out to Collioure and destroy all my private papers.’

On reflection, when he died, I thought, ‘This is a rather odd request because how does he know I’ll still be alive or that I might not be able to come? Somebody else might get into the house first. Surely if he wanted them destroyed, he would have destroyed them.’ Because of that, I didn’t feel that I was poking into something. Apparently, I knew much more than I thought I did when I came to it, as often happens. I’m perfectly satisfied with it. I’ve given his faults as well.

There’s only one thing, which is of no great interest to anyone, that I’ve omitted; otherwise, everything I know is there in the two volumes ... good or bad, most of it good.

Peter Moore

Can I take you back to your very first meeting with Patrick? I’ve looked in the biography so I know, with some clarity, that it happened on 1st September 1955 and you were in Collioure.

You say, ‘When the door of their little home swung open ...’ and you actually describe this moment quite vividly in the book where you are presented with the sight of this 40-year-old writer to whom she is married and they’re quietly living away in France. What was it like? Do you remember?

Nikolai Tolstoy

For me, it was quite strange in one respect because my mother was, for me, a stranger. I couldn’t remember what she looked like and I certainly didn’t know what she was like. I didn’t get on very well with my father and still less with my awful stepmother so I decided one day, that I would go and see my mother. I must have corresponded with her.

We were on holiday in Northern Spain, then I left and when I went to the door, my mother came out and Patrick was behind her and I thought he was standing in a sort of Stephen Maturin way with this gesture. Patrick did that with his head on one side, half smiling.

Peter Moore

Let me describe that gesture because I think it’s quite characteristic of him. It’s almost like the hands are clasped together.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, it’s like this and then he’s sizing you up and smiling but you didn’t quite know what he was thinking. I notice in the books I was able to quote exactly this description of how Maturin stood when he first met Aubrey I think... whether it was shyness. He was quite shy, obviously, because he was a recluse but I think a little bit of it was shyness.

Luckily, we had an enormous amount in common even at that age. Of course, I was only 20 just but I loved the same period and loved history... loved literature of the period that he liked. So we should have got on very well but, actually, we didn’t. I think I was there about three or four weeks and by the end, I’m afraid there was quite a coldness between us. I put it down to, on my part, being very youthful, bumptious and opinionated as most people are at that age and thinking I knew a lot more than I knew.

On Patrick’s side, it was very awkward because he was a great writer and he knew he had this in him but he hadn’t, as yet, published a great deal. He’d published very good short stories and, of course, the children’s books, none of which had I read. I think Patrick himself was on his metal and so we rather clashed. With Patrick, you never clashed in open argument; he didn’t like that but just a coldness developed. There were subsequent occasions when we had a slight difference and he could take offence really easily.

Luckily, because of my unique position in being my mother’s son, he couldn’t expel me from his life and there were quite a lot of people who were simply deleted. In his address book, there were people who were rather like the Soviets; they were just deleted as not existing anymore [laughter].

Peter Moore

I was about to interject when you were talking then as it reminded me that the one thing that you write about is Patrick’s utter dislike of being interrupted. Is that correct? He liked to speak and to be listened to. Is that correct?

Nikolai Tolstoy

He certainly did and quite often, Georgina was amused by this. When he was speaking, he would pause and I remember Georgina did blurt out a comment, out of politeness I’m sure, and Patrick stood up and said, ‘If you will allow me to continue...’ But I mean there had been a pause of a couple of minutes or so and no one knew that he was going to go and say anything [laughter].

He did this when he was interviewed by the press in public I think. I remember someone telling me who was there in America. I think it was two things; one was a natural shyness which he did have and the other was a fear that something bad about him would come to light. Actually, I’ve read everything and there’s nothing I would say was bad or worse than anyone else but he was so hypersensitive about this.

Peter Moore

I suppose as well there is the picture of the brooding author. There’s a particular line in your account of this first visit where he doesn’t explode because, obviously, that wasn’t Patrick’s style but he does remind you that he’s a writer who was being compared with Dostoevsky.

Nikolai Tolstoy

He did say that at the first meeting, yes.

Peter Moore

You can read that in various ways. In a way, it’s a very pompous thing for someone to state about themselves but I think it’s actually very revealing in this moment because it shows that Patrick is aware that he is someone who possesses great gifts. He can write. He knows he can write but, at the same time, he’s just really anonymous. He was very poor as well at that point, wasn’t he?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Very poor, yes, but always very generous and my mother too. They hid their poverty from me; not, I don’t think, primarily out of shame of it. They were living a contented life and for me, it seemed enviable. I never knew that they were badly off but subsequently, when I wrote the biography, luckily, I had all my mother’s accounts from the very earliest days and they show how desperately poor they were.

I was told this story as I was talking to people about Patrick that, on one occasion, she wrote in her diary, ‘I don’t know if we’ve got £25 left in our account. It’s autumn. How are we going to get through to the New Year?’ About four years before he died, Patrick wrote to me and said, ‘This year, I made my first million pounds.’ Not many authors, especially today, have that revolution. Well, there must be some but not many are so poor at the beginning. I think there are very few authors writing in garrets these days.

Peter Moore

I guess there’s something really nice about his career trajectory looking back at it now because we can say that he was fulfilled and recognised eventually but there was a long period that ran up to that. I thought it would be quite nice if I read some of Patrick’s prose out because it’s very distinct and it feels very poetic at points.

This is a little snippet from the third of the Aubrey-Maturin novels which is HMS Surprise from early on in the book. He writes,

‘In Whitehall, a grey drizzle wept down upon the Admiralty, but in Sussex the air was dry - dry and perfectly still. The smoke rose from a chimney of the small drawing-room at Mapes Court in a tall, unwavering plume, a hundred feet before its head drifted away in a blue mist to lie in the hollows of the downs behind the house. The leaves were hanging yet, but only just, and from time to time, the bright yellow rounds on the tree outside the window dropped of themselves, twirling in their low fall to join the golden carpet at its foot and in the silence, the whispering impact of each leaf could be heard – a silence as peaceful as an easy death.’

Nikolai Tolstoy

Wonderful, isn’t it?

Peter Moore

The quality of that prose... the images... I mean there’s no action.

Nikolai Tolstoy

There’s such a succession of them.

Peter Moore

There’s no action at all. There’s no real plot there. This is all pure descriptive writing about a leaf falling off a tree and some smoke rising into the air – the changing of the seasons. Where did that love of nature come from? Do you know?

Nikolai Tolstoy

I know that it came particularly from childhood in Sussex where his father, who was like Jack Aubrey’s father, was always indigent. He was a doctor and was always going in for outré cures. He even proudly invented a gadget to prevent people from going into telephone boxes and not paying the penny. In those days, you had to pay. Immediately, it locked the door behind them so they were stuck until the police came [laughter]. I’m not sure it would ever work but that was what he was like.

He had to move because of his indigence to Lewes in Sussex which, of course, was perfect for Patrick because it was and is still a beautiful 18th-century town but also with its medieval castle. Patrick would go out and play and I recognise a lot of that at the very beginning of Richard Temple which is largely autobiographical. He would wander along the River Ouse looking at fish.

There are little scaps I found written from those days which certainly prefaced this very majestic piece. What’s so wonderful is if it were almost any other author writing today, it would constitute padding between two bits of drama but with Patrick, it all flows. It’s wonderful though how he remembered because he didn’t stay very long in England after that as he was in Collioure. Everything was secured in his memory.

Peter Moore

Was Sussex, in that sense, a really powerful landscape for him or were there any alternative ones that you think were as strong?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Other ones come into it and I think when he first moves into Mapes Court... or somewhere they go, it’s recognisable as being the house that Georgina and I first bought in North Wales. They had lived in North Wales. It was next door but there’s a picture. They lived in a tiny cottage. That makes me remember that he would have had a very vivid picture of North Wales, for example, with the grim winters, mountains and the hunting too.

Peter Moore

How long did it take you from your first acquaintance back in 1955? It must have been very difficult but did you appreciate how good he was? Did he send you his work? I suppose that was at the time he was writing The Golden Ocean and these kinds of preludes to the Aubrey-Maturin novels and the later quite gloomy novels that he wrote when he was a younger, tortured soul maybe.

Nikolai Tolstoy

I didn’t read many of them at that time. When I first stayed, I particularly admired his short stories and I liked all the Irish background, although I still hadn’t been to Ireland. I went the next year to Trinity College. The Virtuous Peleg, which is a sort of comical pastiche of an Irish saint’s life which is now something I’m very familiar with, struck me as brilliant and both funny and touching and captured the essence of this early Celtic literature.

Peter Moore

Was he an encouraging figure for you? You said that, earlier on, you’d got this ambition to become a writer from a very young age. I guess you were moving forward with that. Was Patrick helpful to you?

Nikolai Tolstoy

He was very helpful and very kind. He might easily have thought, and possibly even did think, that some of this was rather jejune but he would always be encouraging. He would be frank but very, very tactfully so you could never be hurt.

Even as a young man when I hadn’t yet written or published anything, his advice was always practical and helpful. They’re now in the British Library but I had letters from him and it’s always constructive and never destructive. He could be of other people but he was very kind to me.

Peter Moore

So your visits became more frequent and almost an annual affair really. You’d spend your summers in the South of France with him. After this initial clashing of horns, if you like, you really became much closer over, say, the 1960s and into the 70s.

Nikolai Tolstoy

We did and although I’m not, as Georgina would say, a particularly tactful person, I learned and it wasn’t difficult to find out how not to upset him and to keep things on an even keel. Sometimes, he would take offence but now I can’t even remember and just remember the fact but nothing happened like the very first and rather disastrous visit. I’m sure if I weren’t my mother’s son, I never would have seen Patrick again.

So many people were cut off from their lives. It could, of course, have been simply that they were too far away. In the address books, there are comical things but I won’t say who it was but there was quite a well-known writer who stayed with his wife. My mother, who never questioned anything Patrick said or did, in the address book had crossed their names out and put ‘Never again!’ [Laughter]

Peter Moore

Can I ask you about the relationship between your mother and Patrick? One of the things that’s really striking to anyone who reads his novels is how time, and time, and time again, they are always dedicated to your mother. It seems like she was such a fundamental part of his life, obviously, but even beyond that, it was a real love match, wasn’t it?

Nikolai Tolstoy

It was. I think his writing was going badly so he went to Vienna and lived with some Austrian princess who let rooms in her castle and there was an agonising letter. He hadn’t received a letter from my mother for a week and he wrote ‘Please, please write. I can’t go on without you.’ That summed it up really for all his life.

Obviously, I saw it all at first-hand and very close up with just us alone, initially, in a tiny one-roomed flat in Collioure so we were really hugger mugger. I slept in a sort of low cupboard under the small wall. I have to say that my mother was not a very intellectual person and she was not particularly well-read but somehow, I think she expressed herself through Patrick and Patrick, in turn, always wanted her opinion. To me, he would often quote humorously what May West said – ‘Don’t give me criticism. What I want is unstinted praise.’ [Laughter]

He recognised it in himself but authors do need that; otherwise, if you’re on your own, some people can get away with ...

Peter Moore

What did she supply that was so important for him? Did she have a real strength of character?

Nikolai Tolstoy

She did, actually. Like Leo Tolstoy’s wife, she typed every single one of his books and sometimes more than once. She had a sort of instinct. She would praise something that she thought was good but I got the impression that he had the gut feeling that what she hadn’t praised wasn’t quite up to scratch. She never tried to impose things on him but cunningly or intuitively steered him into the right paths and he recognised that.

Also, he needed her company and when she died - and luckily he died only two years later - he was just distraught and wandered from Collioure to other places. He had plenty of money so he could go where he liked. He’d go to London but then he’d get restless and go off to New York and back to Collioure. He always came back to Collioure.

Peter Moore

I guess he’s been in this room then.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Oh, often, yes.

Peter Moore

This is another place that he wandered to. He was a very hard-working writer as well, wasn’t he?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Very, yes.

Peter Moore

So even though he had a natural talent and he’d got the books, and we might talk about those in a moment, he worked really hard at what he did.

Nikolai Tolstoy

He was very hard-working and very conscientious. Also, he could be easily put out. If I had brought a friend, which I did once or twice from university, or even if I outstayed my welcome... I know what it’s like because I’ve felt it myself. You’re torn and you want to see someone but when you get back in your workroom, you can’t concentrate because that person is still in the house.

I remember instances of that happening even with me. I think, just the same as me, you afterwards regret it and think, ‘Why was I so testy and impatient?’ Of course, if you’re committed to writing, you can’t escape that.

Peter Moore

What would a working day be like for Patrick? Was he a morning person? Was he very rigid in his time-keeping?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, rigid. He would go straight down after breakfast. In Collioure, he had a strange, tiny place which was much, much smaller than this. It was like a cave. They had a vineyard going down and sloping quite steeply from the house. They had a terrace or balcony and under it, there was a gap and that’s where Patrick did his writing like The Naval Chronicle and things like that. He didn’t have many books around him.

Peter Moore

Just the book of the day...

Nikolai Tolstoy

Exactly.

Peter Moore

...as it was needed.

Nikolai Tolstoy

I’ve got all the books I wanted from his library. I didn’t take away paperbacks or ephemeral things. I can’t say that because a book wasn’t there he didn’t read it because he belonged to the London Library so he would get books sent and returned regularly.

Peter Moore

As we’re on books, let’s just have a think about it because the two characters who are the ones which most people will know him through are Jack Aubrey, the Captain, whose Royal Navy career is full of incident and gallantry and Stephen Maturin who is the quiet philosopher. It’s one of the great friendships, shall we say, in literature, I think. I asked you before we started this to pick two books because I was wondering where these characters come from. They’re obviously compounded from many sources and it’s not a simple question.

But because we’ve got these books here, I thought it would be good just to look at two, one for each. Could you pick one up and let’s have a little look?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes.

Peter Moore

What’s this?

Nikolai Tolstoy

This is Falconer’s An Universal Dictionary of the Marine which is a complete encyclopedia for use by naval captains. It’s dated 1769 so it’s perfect timing. He did use a subsequent edition later than the Napoleonic Wars or slightly later, then he got this one which is, of course, ideal because if it’s in here, then it’s something that Jack Aubrey could and, indeed, would have read.

Peter Moore

Let me just talk about this because it’s incredible to see this. Let’s have a little look. I’m going to hold it myself here now. It’s not a big folio size but it’s probably half the size of that. I’m not quite sure.

Nikolai Tolstoy

It’s a complete dictionary of everything you need to know including orders, etcetera.

Peter Moore

All of these extended scenes where you have the management of the ship at sea of how it wears and tacks and the millions of different descriptions of knots, sails, rigs and strange parts of the ship that kind of litter the novels were probably consulted for in here.

Actually, it’s so funny because I’ve just opened up a random page and I think this is quite typical. You’ve got one of Patrick’s own diagrams here.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Oh, yes!

Peter Moore

Let’s see, what does it say? Let’s have a look. It’s talking about barometric readings. This is all very precise with beautiful sketching. Maybe I could take a photo of this ...

Nikolai Tolstoy

I think that’s the Surprise but I’m not sure.

Peter Moore

I don’t know. What is this? This is obviously one of the ships which is in the novels and, basically, it’s a ship’s plan which shows where the surgeon is and where the lieutenant and warrant officers are [laughter]. In a way, you can see a little bit of his method before the descriptions have begun.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, you can see he was so meticulous and fascinated by detail. Georgina said, ‘The only thing I don’t like about the books is all the technical descriptions,’ but if he heard that someone had read it and found it a bit hard, Patrick always said, ‘Look, you’re not meant to understand it or retain it. You’re on the ship and these are the things that would have been happening. You just take them in your stride and you don’t have to remember them.’

Peter Moore

I’ve seen him in an interview being questioned about this and he said, ‘It just has to be right.’ It’s like a determination. A friend of mine said he had a friend who had sailed in the navy and they only found one mistake in the whole 20 novels [laughter] so I think his level of accuracy was extraordinary.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Extraordinary, yes.

Peter Moore

This is the kind of book that would have been familiar to a Jack Aubrey kind of character.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, exactly. I imagine any post-captain would have had that on board with him.

Peter Moore

Do you want to say anything about Aubrey?

Nikolai Tolstoy

You asked earlier as to where these two characters came from. I’m pretty sure I know. They both come from Patrick himself. Whenever I’m reading one of the books and read about Maturin, I just see Patrick in front of me [laughter]. It’s definitely him.

The Irish background I think is because Patrick went to Ireland more often than people had known and, indeed, it was even suggested that he never went there until much later in life but that’s not true. I discovered he went and even fell in love with a girl up in the North. When I went to Ireland (and I have no direct Irish connection), I fell in love with the country and he did too.

Of course, Jack Aubrey is completely dissimilar from Patrick but, nevertheless, I’m pretty certain that one side of him would like to have been. He would have liked to have been valiant, jovial and a physically big man. Patrick was of average height, shy and, of course, quite slight. I’m sure he wished he had all that confidence. At the time, I remember when he got a good advance and the series was taking off, he rushed and bought a set of solid, silver plates for their dinner at Collioure and Jack Aubrey does actually buy a set of silver plates too at one point [laughter].

I think what he liked about Jack Aubrey was that, on the one hand, he came from a respectable... well, more than a respectable and gentlemanly family; whereas, Patrick’s background was nothing to be ashamed of but, at the same time, they were not particularly grand. They were of German origin. We know that and the father was a bit of a tyrant, also a well over six-foot giant and I think a little bit of a bully. That’s the bad side and Patrick wanted to create, as you say, more of a structured and ordered background for himself through his character.

Sometimes, I see quite often that people criticise Maturin for having been to Trinity where I went and that he couldn’t have gone because he was a Catholic. Once again, Patrick was practically always right because, officially, Trinity didn’t allow Catholics to enter its portals at the time Maturin would have been there but unofficially, it did. I don’t know that Patrick knew that. He knew so much by a tremendous feel for the period so he could often anticipate things and very, very rarely indeed made any sort of error.

Peter Moore

Let’s talk about Stephen then for a moment who is much more like Patrick really in the way he described his stance and how Stephen would be slightly... not a sinister presence but definitely a presence of sorts; often silent, very thoughtful... having secret codes and jotting things down in darkened corners when people aren’t looking. That was very Patrick, wasn’t it?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Very Patrick, yes, exactly. He was quite secretive but occasionally, could flare up and then it would all quickly subside again. In the film, I rather wished they’d had someone who looked a bit more like Patrick but it was still very good.

What I should say is that he had a marvellous sense of humour and that comes across very much in the books. There was no envy when we were together. If I made a joke or told him a funny story about something happening in Ireland, he would love it and burst out laughing.

Peter Moore

Brilliant.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Many of those stories come into his books.

Peter Moore

Which book have you chosen for Stephen Maturin?

Nikolai Tolstoy

This is actually what I would have chosen. I can’t say where Patrick got the Irish side of Stephen from so well and having been there for five years myself at Trinity, he doesn’t put a foot wrong even with the slight Irish intonation.

If it were me choosing, I would have chosen these inimitable memoirs of the same period, the memoirs of Sir Jonah Barrington which are full of wonderful accounts of wild Irishmen, their habits, duels and everything else covering exactly the same period.

Peter Moore

This is a really important aspect of the novels which is the Irish flavour of Maturin. Obviously, in Master and Commander, there’s this very explicit plot-line which follows the United Irishmen.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, of course, and Dillon is a former United Irishman.

Peter Moore

There’s a real tension there in politics that he’s trying to eke out.

Nikolai Tolstoy

I think like many people, including me who loved Ireland and went there as Patrick had done before the war, just got carried away with it. It’s changed a lot now, I fear for the worse. As I’m writing my own autobiography, I’ve been writing about my Trinity days and people might think now that’s me being Irish but it actually was like that with wonderful eccentric sayings and so on.

Patrick loved it when I would recount these when I arrived on occasion from Trinity. I know he noted them down because some of them were direct quotes.

Peter Moore

Wonderful. Music: I just thought I’d ask you about Patrick and music for a little bit because the novels, in a way, start with that scene in Port Mahon. There’s a musical concert that’s being played and that’s where Maturin and Aubrey first meet. In a way, the point where their two very different personalities do meet throughout the series is in their love of music and they hold it in such high regard.

There are lots of nice scenes of them in the Great Cabin with the dead water behind and music in the air in front but did Patrick have a real love of music himself?

Nikolai Tolstoy

He did. There was a very good programme and we used to have one like it on the radio, France Musique. Instead of, like Classic FM, playing tiny snippets, it would play entire symphonies. He recorded them and then played the tape recordings. I was listening to one and he said, ‘Now the next piece is by Saint-Saëns.’ There was a sort of scrabbling noise and Patrick turned it off because Saint-Saëns was far too modern for his liking. He was steeped in the music of Boccherini, Mozart, Haydn and so on.

Peter Moore

This also brings me to another point which is about him being very much a kind of man out of time in a way. There’s a wonderful quote. This is from Patrick’s diary in 1996, actually, which goes into your biography. It’s a wonderful snippet because he writes

‘I tried putting up the vacuum cleaner – frightful struggle – holes mismeasured, instructions misunderstood but at last, I got it into place with the machine charging; a rotten day but at night, I dreamt a JA and SM piece with great pleasure; visual images, SM being smaller and older than I’d thought in an old black coat.’

I think it’s a wonderful entry because there he is taking solace in his imagination and the past. I don’t know why he couldn’t work out the vacuum cleaner which couldn’t have been that complicated.

Nikolai Tolstoy

He couldn’t work anything mechanical.

Peter Moore

But was he that bad?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Yes, he was. Georgina was very amused because when we stayed there a couple of times after Patrick sadly had died, we had to sort out the house. The house couldn’t be set on fire because it was all made of concrete but it was completely wired by Patrick and so, naturally, cables were dangling all over the place [laughter].

He loved to work things out. I quoted him the other day to Georgina because I couldn’t find something important and I discovered, when I was going through things and I think in a silver teapot, a note by Patrick. He left notes for himself. He talked to himself and wrote notes that we found. They would say things like ‘Supper on left-hand side of third shelf in fridge.’ The one in the teapot simply said ‘Never, never put anything precious where you think it’s safe.’ [Laughter] I lost something the other day like that.

Peter Moore

Yeah, exactly [laughter].

Nikolai Tolstoy

Even when my mother wasn’t there, he continued these dialogues with himself.

Peter Moore

That’s interesting. The other thing about technology, I suppose, which is a connection is how many of these car crashes they seemed to have.

Again, this is the man out of time and someone who is so at ease in a 38-gun frigate at sea in the Mediterranean but could not, for the life of him, be trusted with a Citroën 2CV on the roads of France. They had so many car crashes and they were all somebody else’s fault.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Always someone else’s fault, yes. I’m sorry to say that they usually resulted because Patrick had that attitude. He’d be driving on the wrong side of the road and he’d shout out. Of course, they couldn’t hear him say, ‘Get out of my way, you idiot!’ When they drove off the side of the canal, they nearly drowned and couldn’t get out.

I remember once we were driving with Patrick and my mother and we were going up a rather steep and perilous road creeping up the side of one of the mountains of the Pyrenees. Georgina, who can drive unlike me, clutched my hand and said, ‘There’s something wrong with the car, I’m sure.’ I said, ‘I’m sure it’s alright,’ but then she got so nervous, I said, ‘Oh dear, Patrick, I think Georgina is worried that there’s something wrong as we’re bumping a lot.’ He said, ‘No, there’s nothing wrong whatever. That’s ridiculous.’ He went on and my mother said, ‘Patrick, I think I can hear some bumping.’ We got out and it turned out that the last nut on the back rear wheel on the outside towards the falls, which looked like miles below, was still holding it together. The wheel was about to fall over the edge and us, I guess, with it.

Peter Moore

Oh, crikey.

Nikolai Tolstoy

He still wouldn’t admit that there was anything particularly wrong.

Peter Moore

There was this proximity to danger as well. I think you say that, for many years, they slept in a bedroom with a box of dynamite above their heads.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Oh, yes, I’d forgotten that. Yes, exactly. Patrick himself insisted, at first, on operating the dynamite. My mother described in her diary that it flew past her head and that actually did make Patrick realise so he got in some Catalan miners from over the border to do the rest of the work. He always had to try and do it himself and he loved doing things with his hands and fingers, good or bad.

Peter Moore

I should say that apart from the books in here, there are lots of Patrick’s things and some really quite curious objects. Over in the distance, I can see Stephen Maturin’s pincers I think.

Nikolai Tolstoy

That’s it, yes, and also a curious instrument for working out latitude. I’m not even sure how it works.

Peter Moore

Yes, that’s a curiosity but then down another direction, there’s a Noah’s Ark that he made for your children in the ‘70s. It’s very charming.

Nikolai Tolstoy

He built it in the garage and between writing chapters, he would go in there and work away at it. It’s got a very amusing letter inside and I’ve still got the letter. It says something to the effect of ‘The odd creatures with marks on their backs are meant to be leopards.’ I can get the letter.

Peter Moore

Down there, there’s his Trilby hat and briefcase.

Nikolai Tolstoy

I keep his hat and his gown that he got when he was given an honorary degree at Trinity. Rightly, he was very pleased with that.

Peter Moore

When all the success came in the 1990s, which was a success on an absolutely huge scale, did it change him or did he remain very much the same?

Nikolai Tolstoy

He remained very much the same. I mean he would indulge in a cheerful, boastful way saying that he had earned his first million pounds because he knew I would also be entertained and pleased by it. He wasn’t super-modest but, essentially, he didn’t change. I think he felt that the earlier books were good and that people simply hadn’t had the sense to recognise that.

Peter Moore

What about the paranoia? I suppose, in a way, the Patrick that a lot of people hold in their minds is the Patrick of, say, about 1997/98; this enigmatic creature who writes beautiful books beyond question, brilliant books but who is crabby and does not like to be interviewed.

Obviously, from the inside, you know this was the point where he was being pursued by Dean King for information about his private life that he did not want to give up. There was a whole question about his identity and, obviously, the change of name from his early life and whether he’d been to sea or whether he’d been Irish at all. Did this make him a paranoid character?

Nikolai Tolstoy

It did to some extent. Yes, it did. Because he was so famous and so successful, of course, it aroused a certain amount of genuine envy among rather ludicrous people. If they’re ludicrous people, then it’s ludicrous to worry about them but Patrick did worry. It still lingered on, this fear that… well, there were two material things which were the facts that his name had been changed and that he wasn’t, in fact, Irish at all. He lived in dread that people would find that out.

Even in the privacy of his house, there were books that had been written by his father, Dr Russ, which I discovered but they had been hidden away because, of course, it gave the game away with Russ as the surname. I think it made his paranoia worse and not better that he became famous because there was all this danger that somebody somewhere would find out.

Of course, the ‘fool’ King, as Patrick quite rightly called him, seemed to be doing just that. In fact, he was and what’s more, Patrick’s worst fears were realised; that he’d make himself open to misrepresentation.

I do remember once he was at Trinity and they let him have rooms there because of his honorary degree. I went over there and slept in the same room on the sofa. Patrick said to me, ‘I’ve just had a letter from this man, Dean King, who wants to meet me.’ I was very surprised because it was one of the very few occasions – perhaps the only one I can remember – where he actually not only asked for my advice but clearly wanted it and would take it.

He said, ‘I don’t want to see him. I think it’s a mistake. What would you do if it was you?’ I was quite well-known by then so it was similar and I said, ‘To be honest, I think these people are going to write anyway. I’d be inclined to see him because you can’t control what he writes but at least he will know the truth. Actually, the truth is usually more appetising than lies.’ Patrick looked very happy suddenly and he said, ‘You’re right. I’ll do that. I’ll write to my agent tomorrow,’ because the correspondence was going through the agent.

Dean King, getting desperate, had published, by pure mischance for him in some American, well-known magazine, an article about Patrick. I don’t think it was disparaging but it was certainly wrong-headed. The agent sent this to Patrick and Patrick flew into quite a rage and said, ‘I’m not going to see that scoundrel.’ So poor Dean King - the one thing he wanted was to meet the great man – destroyed that chance inadvertently himself.

Peter Moore

How would you like Patrick to be remembered? Obviously, you have your own very close relationship with him. I suppose it should be said that there’s only a very small number of people who actually really knew Patrick at all.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Very few.

Peter Moore

Maybe your mother, you and maybe a few other close associates.

Nikolai Tolstoy

Even the people who came like Willian Waldegrave. He was a genuine fan and I think Patrick liked him too because Waldegrave was Provost of Eton. Patrick didn’t quarrel with him and he was about the only person he didn’t. Waldegrave has actually been quite a good ally. I don’t say this to make myself the only person who did know him but I just know they never knew the real Patrick because he put on a completely different… well, not completely different but another Patrick for their benefit. He was probably more frightened that they would find out and be disillusioned.

Of course, they wouldn’t have been disillusioned. There wasn’t anything bad to hide at all I didn’t think. I now, more or less, know everything, even the odd discreditable thing, especially in his youth, which he was so alarmed about. He was also distressed by the fact that he’d not had any of the smart education which other people had who he looked up to more than they deserved I guess. In fact, I think I’m right (from memory and you may remember) in that I don’t think he ever passed a single examination [laughter].

Peter Moore

Which is an incredible thing, isn’t it?

Nikolai Tolstoy

He left school and, of course, didn’t go to university and was chucked out of the RAF.

Peter Moore

But when you look at the depth of learning that he had and the fact that he couldn’t get through an exam …

Nikolai Tolstoy

I know. It’s extraordinary. I wonder if he was, as I was to some extent, gripped with nerves. An exam does put you on your metal in a horrible way. I can quite see Patrick getting so tense that he wouldn’t be able to do anything, even though, of course, he knew miles more.

Peter Moore

So that question again to you, how would you like Patrick to be remembered?

Nikolai Tolstoy

Well, I’d like him to be remembered, as he would, as someone who’s given immense pleasure to an enormous number of people. I’ve sold them to the British Library but, luckily, my mother religiously kept all the letters. I think one says ‘fans’ and I think another one, a very small one, says ‘stupid letters’. [Laughter]

Peter Moore

Listen, it’s been a real pleasure. I’m going to keep looking at his books after we’ve finished this, hopefully. What a great thing to talk about Patrick and remember his writing and his life.

Nikolai Tolstoy

I love talking about him because it brings him back to life. Actually, even though he had this acerbic side… I know memory edits things but I can remember everything and all I really think of is a very kind, extremely generous person and someone who, after all, gave his life to making other people happy by reading his books •

Coda

That was me, Peter Moore, talking to Count Nikolai Tolstoy about his stepfather, Patrick O’Brian. Please do let us know if you enjoyed this interview and we’ll see if we can produce some more of them.

In the meantime, on Unseen Histories, you can discover all sorts of stories about the past. There are author interviews, original historical features and much more besides. It’s unseenhistories.com. Please do check it out.

Thank you very much for listening. Goodbye.

Transcribed by PODTRANSCRIBE.

Further Reading

Nikolai Tolstoy, Patrick O'Brian - The Making of the Novelist 1914 - 1949 (Century, 2004)

Nikolai Tolstoy, Patrick O'Brian: A Very Private Life (William Collins, 2019)

Dean King, Patrick O'Brian: A Life Revealed (Henry Holt, 2000)