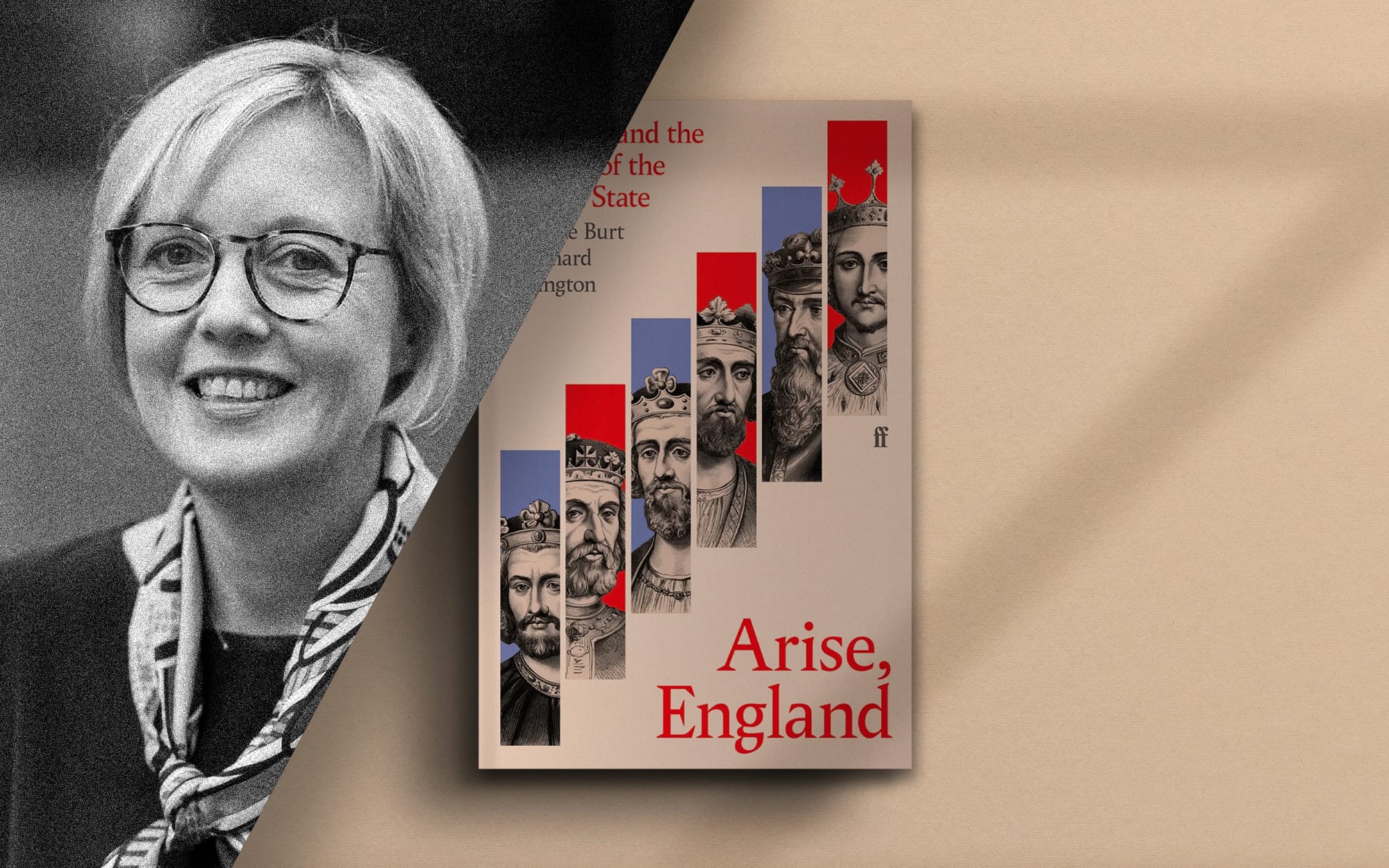

England Arising (1199 - 1399) with Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

The medieval historians Caroline Burt and Richard Partington tell us about a decisive two centuries in the English national story

The two centuries between 1199 and 1399 were unsettled ones in England. They brought civil war, regicide and rebellion. There were conspiracies and revolts, deadly plagues and dramatic treaties.

Six Plantagenet kings ruled during these years: John I, Henry III, the first three Edwards and Richard II. In a new book, Arise, England, the Cambridge historians Caroline Burt and Richard Partington have used the reigns of these six kings to frame a crucial period in England's national story.

The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were, as the authors point out, a perilous time. But, brought together, they were also an era of tremendous and lasting progress.

Unseen Histories

The first striking characteristic of Arise, England is that it is written by two authors. Can you tell us how this collaborative project came about?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

We’re married to one another! And we’re both Cambridge historians who research and teach medieval British history.

Inevitably we talk about our work quite a lot, and around a decade ago we realised that we both wanted to communicate – to a wider audience than our students and other people in the academic community – a national story that seemed to us dynamic, enthralling, and, because of many contemporary resonances, relevant.

Unseen Histories

Arise, England tells the story of one nation over two centuries through the reigns of six kings. You start with the infamous King John. Is he every bit as bad as his reputation suggests?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

Essentially, yes. For John’s contemporaries, his presence in Hell was going to make it fouler still. He was in certain respects a highly able man, but his cognitive intelligence and administrative ability were outweighed by his paranoia, untrustworthiness and cruelty.

He was not a man you would want to meet down a dark alley, especially if he’d been drinking …

Unseen Histories

If King John could be labelled the villain of the pack, which of your half dozen would be considered the hero? Why?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

Edward III. Cognitively and emotionally intelligent. Visionary. Brave. Self-critical. Hard-working and responsible. Charismatic. Funny. Obsessive. Allowed rich widows and his daughters to remain unmarried if that was their preference. Beloved and feared.

His presence in the records of government is almost electric in its quality. But Edward I was also a great king: highly intelligent, dutiful, driven and formidable. He perhaps lacked Edward III’s flexibility at times of crisis.

Unseen Histories

The above question may seem simplistic, but one of your arguments is that the different kings had a tremendous amount of agency and that the force of their characters was truly felt across the realm. Is this right?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

Yes. English kings stood at the head of a powerful governmental and legal system even in 1199, and the overarching story of Arise, England is how that system grew and consolidated across the ensuing 200 years.

By the mid-fourteenth century, the king at Westminster could order criminal suspects to be found and arrested in Bristol, and have them before him for questioning two days later. He could send powerful judicial commissions into the localities to try rogue noblemen or judges suspected of corruption, and the system would draw up charges and levy huge fines accordingly.

At such times, the king’s justice was described as lying ‘heavily on the country’. Kings like Edward I and Edward III were giant, almost legendary figures on the national and international stage. Conversely, the rule of an irresponsible, lackadaisical and idle king like Edward II could lead to terrible problems in the shires.

Petitions for redress were not answered, necessary judicial commissions were not issued, the realm was not defended against invasion by enemies and society began to break down – as territories were overrun and men started to take the law into their own hands through rebellion and other means.

One of the lessons of the book is that, for all that state growth derived from structural factors such as Europe-wide political ideology and demand on the part of ordinary people for access to the king’s law, the state advanced most under the leadership of the great warrior and law-giving kings, Edward I and Edward III.

Unseen Histories

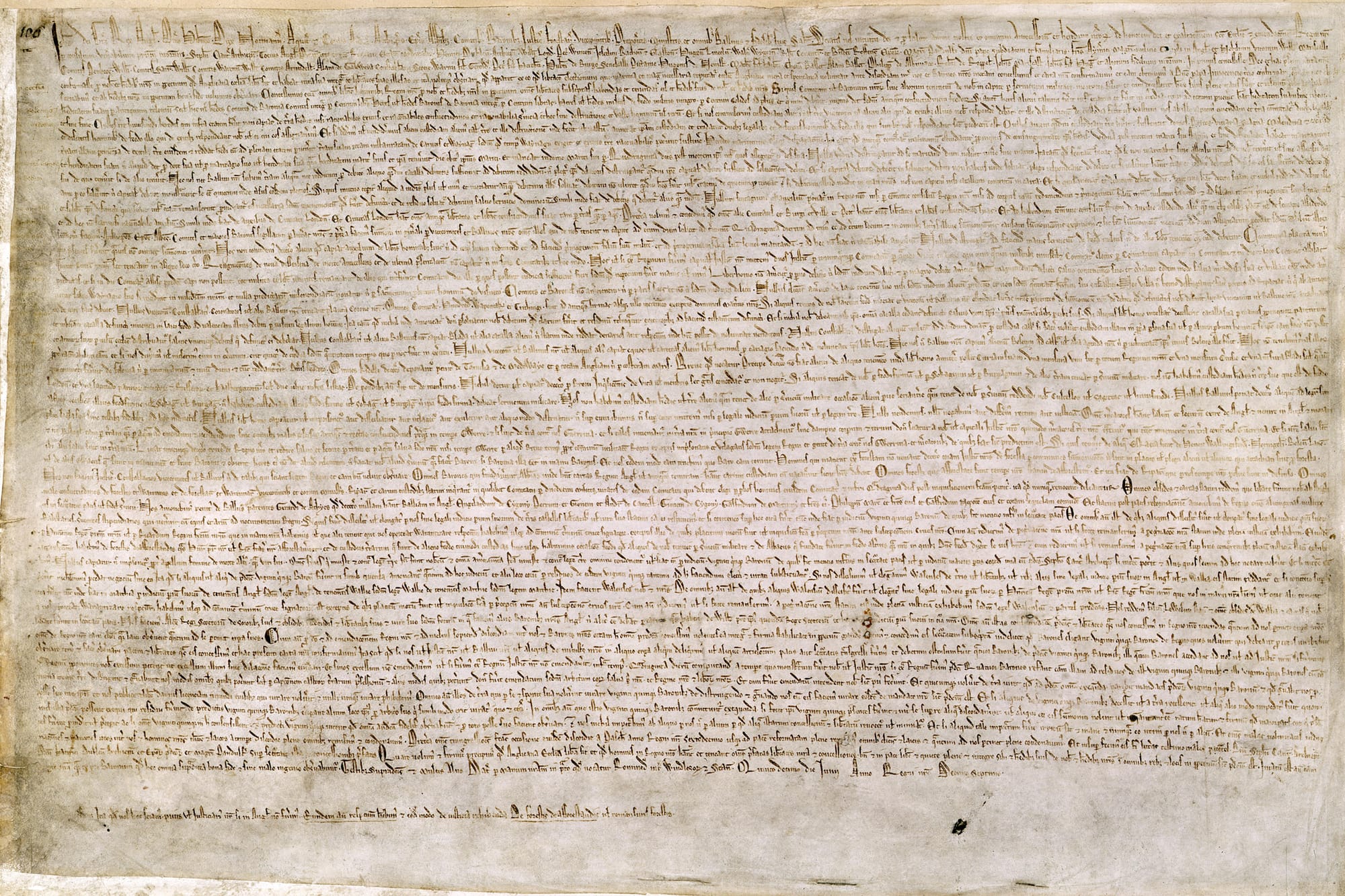

You have Magna Carta in 1215 as an important opening point in your narrative. How novel was the principle (that the king was subject to same laws as everyone else) that it laid down?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

The idea that a king who abused the law was a tyrant was not new. However, the principle in Magna Carta that the king must abide by the same laws as his subjects, and the acceptance of this principle after John’s death, were novel.

The effects of the confirmation of Magna Carta during Henry III’s minority were transformative. It was now no longer possible for a king to exact arbitrary taxes or ‘sell’ access to justice – expedients to which John had regularly resorted to fund his wars.

Taxation now had to be recognised as necessary and agreed by those who would be taxed, and this led to a system of national taxation and, with it, to Parliament, the principal forum through which the need for tax was discussed and consent to it agreed. Magna Carta therefore gave rise to the most important feature of the UK’s political constitution today.

Unseen Histories

Conflict is a running theme throughout your period. Edward I is particularly remembered for his conquest of Wales and his subsequent confrontations with the Scots. Was this expansion opportunistic or was it part of a grand vision for a greater England?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

It was both. Like many monarchs in the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Edward I was influenced by European political and legal treatises that increasingly emphasised the unique authority of monarchs, and their right to exercise sovereignty in the territories over which they believed they held sway.

Llywelyn ap Gruffud had acknowledged the English king’s overlordship in return for being recognised as prince of Wales by Henry III, and in the early 1290s the Scots did the same in respect of Edward I – when they asked him to adjudicate the disputed Scottish succession.

For Edward, that recognition was meaningful, and he believed he was within his rights to require that his overlordship was acknowledged and acted upon in practice. (He also believed he had a personal duty to the Crown of England to insist upon those rights.)

At the same time, he was a practitioner of Realpolitik as well as a political opportunist, and both of those traits undoubtedly fed into his handling and treatment of the Welsh and the Scots, as he sought to strengthen England’s geo-political position in wider Europe.

Unseen Histories

Were you able to include any women’s voices in your account?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

The queens of Henry III, Edward I and especially Edward II – Eleanor of Provence, Eleanor of Castile and Isabella of France – were politically important and Arise, England reflects this.

Other women, such as Alice Lacy, countess of Lincoln also appear where they played an important role in local politics. Readers who are interested in women at the heart of medieval English politics would enjoy Helen Castor’s She-Wolves, a brilliant book.

Unseen Histories

The social and economic disorder brought about by the Black Death in the fourteenth century was extraordinary. We have had a smaller version of this, with COVID-19, in our own times. Did experiencing the one help you write about the other?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

That is an excellent question. At one level, the COVID-19 crisis made little difference to our perspective, because, even without COVID-19, we knew how devastating and crippling the Black Death had been.

That said, Edward III’s fierce insistence that political elites act responsibly in the light of the Black Death was rather thrown into relief by trips to Barnard Castle and cheese and wine evenings in Downing Street …

Where the COVID crisis and its aftermath had the most significant effect on our thinking and our narrative was actually when delayed economic crisis converged with political crisis in the 1370s. The strong sense of suspicion of elites, and concerns about corruption, together with a delayed economic shock all resonated with us during the economic crisis that followed on the heels of COVID.

Unseen Histories

Both of you authors live and work in Cambridge, one of Britain’s great centres of learning. Is this a good place to research the High Middle Ages?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

Yes. We have wonderful colleagues with whom to swap notes, access to some of the best libraries in the world and wonderful students to teach, whose questions and ideas have helped shape our historical views over many years.

But we could name many outstanding History departments in UK universities, full of brilliant colleagues, and engaged and insightful students, and, in an electronic age, internet-based access to both terrific primary and secondary medieval sources is possible from anywhere in the world.

Unseen Histories

Arise, England is superbly erudite. Is there any particularly new or surprising scholarship within it that you were especially excited to convey to a non-academic readership?

Caroline Burt & Richard Partington

It’s very kind of you to say that! For Richard, this was the first time he had written in an all-encompassing way about Edward III, on whom he has conducted research for many years.

He was excited to research the tyranny of Edward II between 1322 and 1327, and that of Isabella and Mortimer between 1327 and 1330, and to realise that this was really a single period of tyrannical rule and – just as importantly – insurrection against it in the country, in which the deposition of Edward II was arguably a big hiccough rather than a fundamental shift.

Caroline was shocked to realise how paranoid and problematic Richard II was, so early in his rule, and relished putting together a picture of the 1380s that she felt made sense. More widely, we were excited to convey to our readers the complex and fascinating ways in which ideology, circumstances and individual agency came together to produce fundamental change – as well as a gripping historical narrative 𖡹

Richard Partington is Senior Tutor at St John's College, Cambridge.

Arise, England is their first trade publication.

Arise, England: Six Kings and the Making of the English State

Faber, 4 April, 2024

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0571311989

"An absorbing and eye-opening account of what the Plantagenets did for us"

– Helen Castor

Between 1199 and 1399, English politics was high drama. These two centuries witnessed savage political blood-letting - including civil war, deposition, the murder of kings and the ruthless execution of rebel lords - as well as international warfare, devastating national pandemic, economic crisis and the first major peasant uprising in English history.

Arise, England uses the six Plantagenet kings who ruled during these two centuries to explore England's emergent statehood. Drawing on original accounts and arresting new research, it draws resonances between government, international relations, and the abilities, egos and ambitions of political actors, then and now.

Colourful and complicated, and by turns impressive and hateful, the six kings stride through the story; but arguably the greatest character is the emerging English state itself.

"Burt and Partington show precisely and engagingly why the Middle Ages matter"

– Dan Jones

With thanks to Tara McEvoy