Bennelong and Phillip with Kate Fullagar

Kate Fullagar on two of Australia’s foundational figures

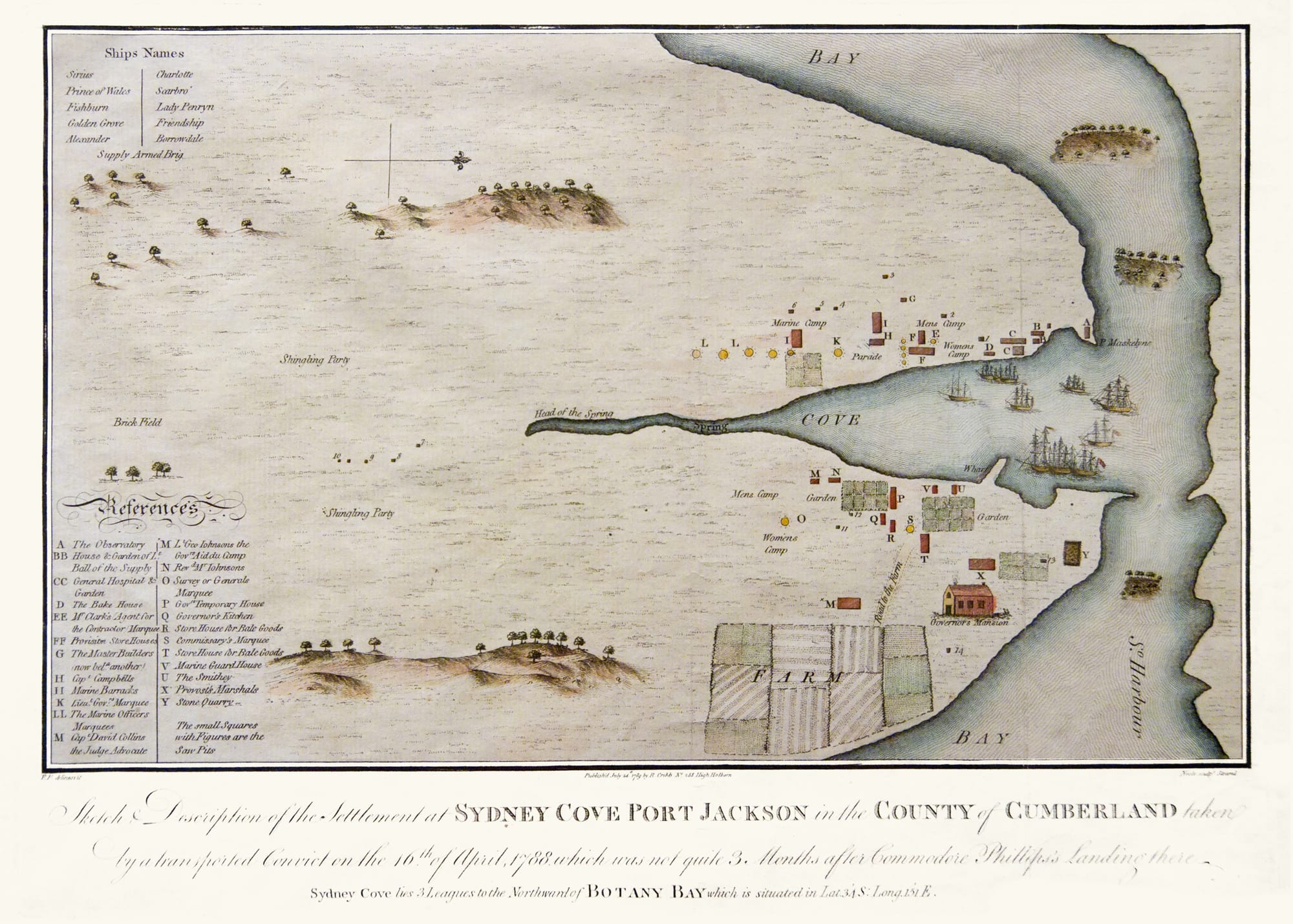

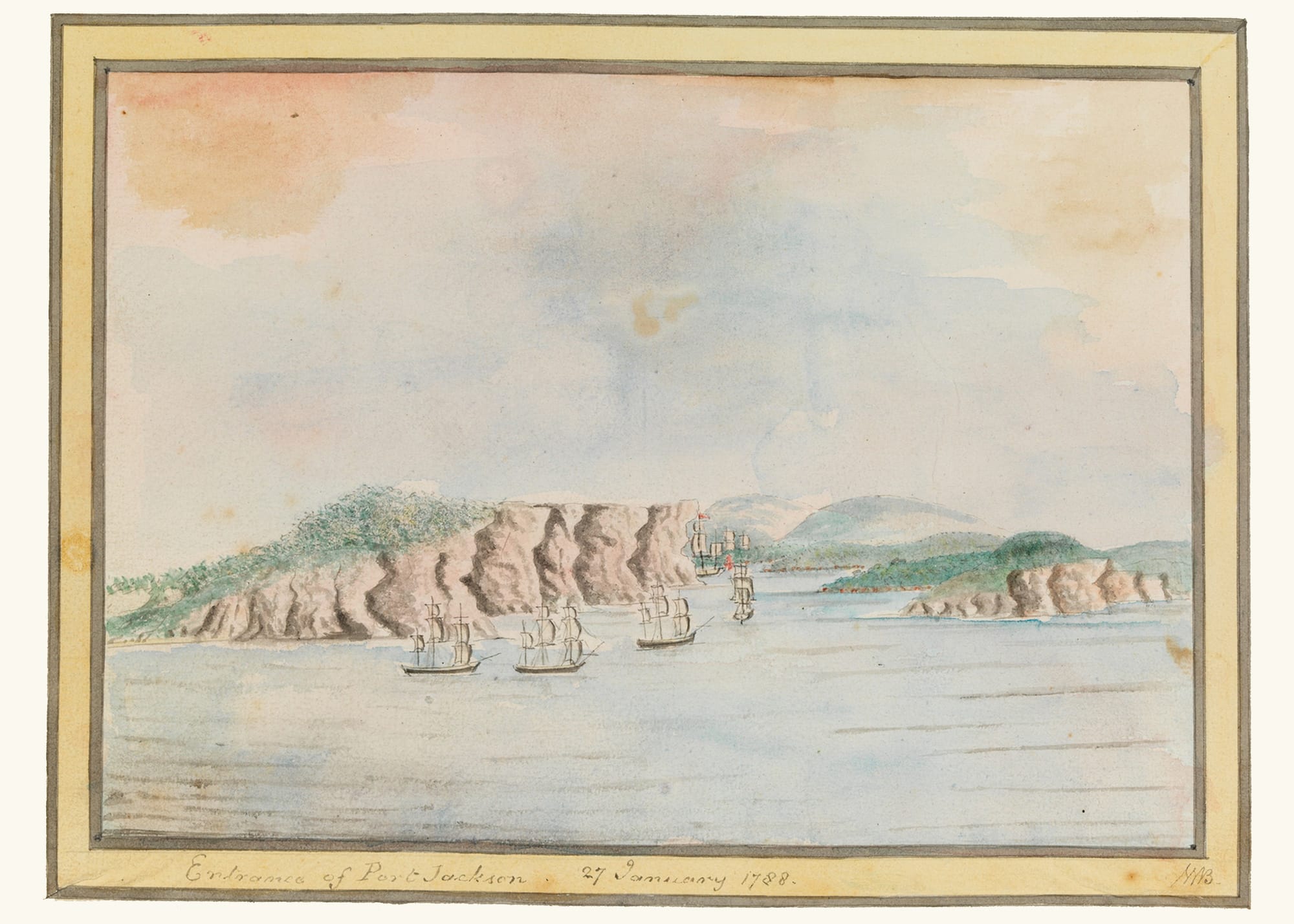

The relationship between Captain Arthur Phillip and the Wangal man Bennelong is one that has long intrigued historians. It began in 1789, a year after the arrival of the 'First Fleet' of British ships in Sydney Cove. Ever since it has been viewed as a highly significant moment: the first time that a British coloniser and an Indigenous person interacted meaningfully.

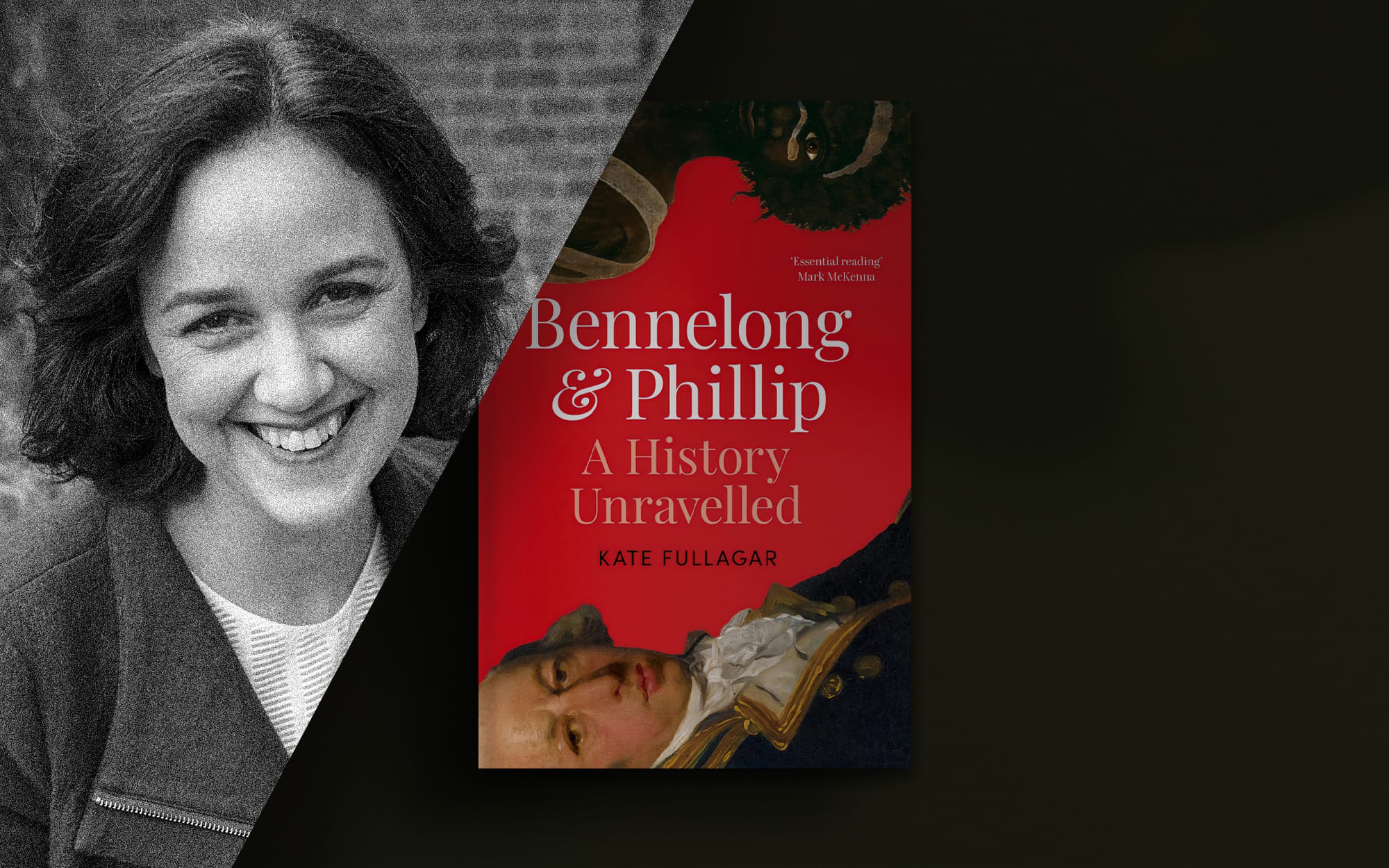

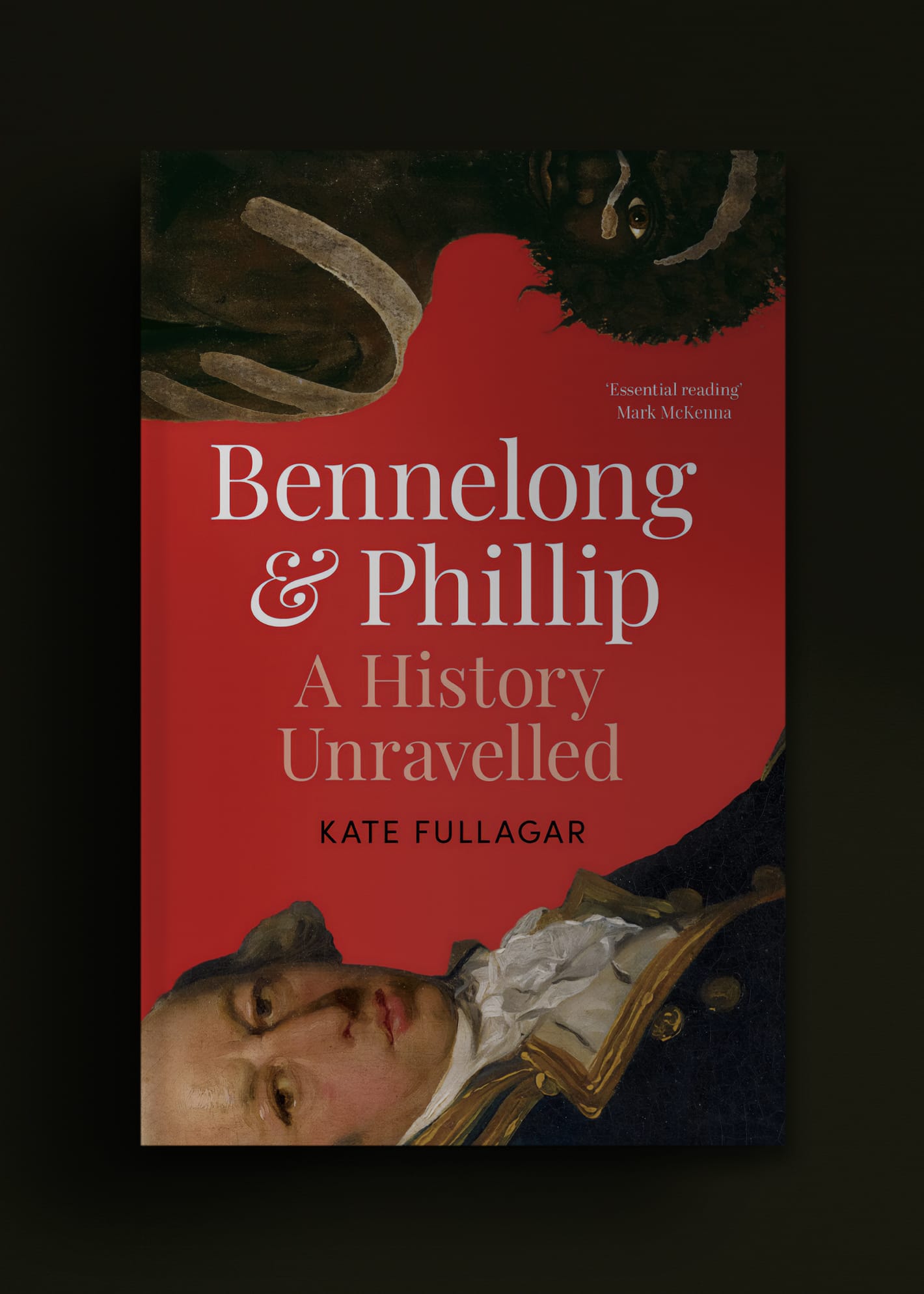

In her book, Bennelong & Phillip: A History Unravelled, the historian Kate Fullagar evaluates the story anew.

Where did each man come from? What were they trying to achieve? Where did the power truly lie in their relationship? What do they symbolise for Australia today?

Unseen Histories

‘Bennelong’ and ‘Phillip’ are names that are instantly recognisable to an Australian readership. Could you introduce these figures in your own words, though, and tell us why the relationship between them is of such significance?

Kate Fullagar

Those names appear all over Sydney (and less frequently over the rest of Australia). Phillip was the inaugural governor or the colony of New South Wales, from 1788 to 1793. Bennelong was a Wangal man who became the most important Indigenous negotiator with the colony in its early years.

Since New South Wales went on to inspire the growth of other British colonies, which then in 1901 federated into a single nation, Phillip has come to be seen as a national ‘Founding Father’. You find islands, parks, schools, suburbs, and pools named Phillip all over the country. (He is also the reason why most Australian Phillips you might know are spelt with two Ls where English Philips usually have just one L.)

Bennelong is not as deeply entrenched in the national cultural landscape, but his name does grace the peninsula on which the famous Sydney Opera House stands (Bennelong Point).

There are also electorates, restaurants, thinktanks, and – strangely enough – hedge funds named after him. The name Bennelong has come to symbolise various things – for some, it means the assimilation of Aboriginal people into settler culture while for others it stands for the loss that follows settler colonisation.

Together, Bennelong and Phillip conjure the first personal relationship between the Indigenous people and the British colonists.

My book is about upturning some of the central assumptions about that relationship, and also about both individual men. It questions the idea of Phillip as a national father and of Bennelong as a symbol of assimilation or loss. My portrait of their relationship shows rather that Phillip is better understood through an imperial lens and that Bennelong represents agency and survival.

Unseen Histories

You write that Bennelong’s story is ‘potent and evocative’. He memorably appeared in Eleanor Dark’s 1941 novel The Timeless Land. Has he come to symbolise a much wider history?

Kate Fullagar

As I’ve intimated, Bennelong has come to mean different things to different people. Even among Indigenous people, he has a mixed reputation – often of being a proud diplomat but sometimes of being a sell-out, even traitor to his people. Local Indigenous communities have though, of course, always remembered him. Non-Indigenous people largely forgot him in the nineteenth century, when most settlers tried to forget their dispossessive and penal origins.

But Eleanor Dark reminded settler readers of his history in that 1941 novel. In many ways, Dark served Bennelong well, rescuing him from the condescension of selective posterity, and also shining a light on his agency in helping Phillip to achieve order in the first colony. The Timeless Land, though, awarded Bennelong a very grim ending. Despite his brief moment in the sun, Dark decided that his ending was tragic, a man trapped between two worlds, which in turn went on to suggest only unhappy things about the possibilities for Aboriginal people under colonial regimes.

Dark did not see that Bennelong was far from a tragic figure. She followed the lead set by the colonists of Bennelong’s day, who could not fathom a man who simply walked away from the colony after getting to know it so deeply. They had interpreted his rejection as ‘backsliding’, but his absence from them was simply a presence elsewhere. Bennelong had decided that re-immersion back with his own people was now the better way to preserve his culture.

Unseen Histories

What were the circumstances of Bennelong and Phillip’s first meeting?

Kate Fullagar

Phillip had been ordered by the British government to “open an intercourse with the natives.” For the first year of settlement, he singularly failed to entice any Aboriginal person to speak with him at all.

In late 1788 Phillip kidnapped a man called Arabanoo, who was meant to satisfy this purpose. Arabanoo, though, died from a smallpox epidemic that flared a few months later. In November 1789, Phillip tried again, kidnapping Bennelong and another man called Colebee. They were shackled in leg irons. Colebee, however, quickly escaped. That Bennelong did not follow has long suggested to historians that he was some kind of sell-out, but in my book I argue that the two men probably came up with a plan – that one would flee back to warn their people of colonial capacities while the other would stay to learn as much as possible about the newcomers.

Unseen Histories

Arthur Phillip appears to be very much a product of his time. But as well as a naval officer and ex-farm manager, you dwell on the fact that he also had a more opaque history as a spy in pre-revolutionary France. Are many people aware of this?

Kate Fullagar

It’s not well-known, but neither is it a total secret. Few historians know what to make of the evidence. I have enjoyed the interpretation of some Phillips hagiographers that he was a ‘naval intelligence officer’ rather than a spy. Either way, he certainly was commissioned by the British government to travel to France in the early 1780s to see if Britain’s greatest foe was secretly rebuilding their navy (after a promise in the 1763 Peace Treaty that they would not). Phillip confirmed that they probably were, which in turn led Whitehall to watch French operations more closely through the 1780s. The British fear of French rearmament was what finally triggered the decision in 1786 to establish a penal base in the southern hemisphere.

The relationship between espionage and empire in the eighteenth century could be taken much more seriously than it has been. Australian historians have, I think, been too distracted by the issue of convict dumping to see the wider global forces behind the origins of New South Wales.

Unseen Histories

Writing about Bennelong & Phillip generates several storytelling challenges, particularly in regard to perspective and nuance. You have responded to this in a highly creative way in an attempt, as you put it, ‘to move beyond the limitations of typical Western ways of writing about the past’. Can you tell us more about this?

Kate Fullagar

I narrate these two entwined biographies in reverse order: that is, we start in the present, trace their posthumous reputations backwards, arrive at their deaths, then plot their later lives, their time together as diplomatic counterparts, their first meeting, their younger lives, their childhoods, their births, and finally their origins in blood and place.

I chose this approach for two main reasons. The first was that it seemed to suit what I wanted to say about these two men: chiefly, that we should reverse, or at least upturn, our understanding of them. Their later lives best demonstrate why. Phillip’s last decade was spent engaging in the British war against the French Revolution while Bennelong’s was spent re-engaging in local ritual battles with harbour clans.

First encountering these men in such places colours how we then understand their more famous earlier period of negotiation with each other. Meeting Phillip on English counter-revolutionary shores tells us key things about his politics and his imperial focus. Meeting Bennelong happily and fully ensconced back among his own people negates his age-old reputation as a tragic loner.

Second, the reverse approach helps to address some mounting calls for a more critical understanding of what modern western history-writing can invisibly do. I was inspired by the recent work of one of my old friends, Priya Satia. Her book Time’s Monster (2020) details how modern progressive ways of narrating the past – which often imply that the world always gets better or freer into the future – can work to license or justify the means to history’s ends.

In imperial settings, this often means that the violence of empire is implicitly licensed or justified by the ultimate end of modernity. My book in no way escapes all the problems of history-writing but I hope it prompts readers to be more aware of how powerful narrative mode can be. I wanted to be disruptive rather than distracting.

Bennelong did not die a broken man; he just died having turned his back on colonial culture, which to colonists could only suggest tragedy. Today that image of Bennelong is slowly changing, as we confront the scattered evidence of Indigenous esteem for the man that has been hiding in plain sight.

Unseen Histories

Those unfamiliar with Bennelong’s story might suppose that it is confined to the area around Sydney Cove. In fact, one of the most significant parts of his story takes place when he sails to Britain (or Berewal as the Yiyura called it). What was the purpose of this visit?

Kate Fullagar

Yes, Bennelong went to Berewal with Phillip when the governor retired in 1792. He stayed for nearly two years, returning home in September 1795. Because Bennelong is rarely awarded a political sensibility, few have known what to make of this trip. But in my book, Bennelong is an active political agent. In 1792 that means he was still committed to the idea of negotiating and mediating with the colonists to best preserve peace, and so following the British leader back to his home makes sense (Bennelong switched to a mode of forsaking the colonists from about 1796).

In 1792 Phillip was also thinking politically. I argue that he invited Bennelong to London in order to prepare him to sign some kind of legal settlement. Phillip knew that the British empire had always designed treaties for Indigenous land before 1788 (even if some of those treaties were dubious). He assumed that it would have to treat one day for New South Wales. In the end, though, there was no treaty. This failure has further stripped the politics out of our memory of the event. But just because a political arrangement never eventuated does not mean that it was an impossibility. Historians have to keep counterfactual possibilities alive in their minds in order to see what might now no longer be obvious.

I should add here too that Bennelong travelled to Berewal with a younger Wangal man too – a man called Yemmerrawanee. Sadly this youth did not survive the disease impact of the journey and died in Eltham in May 1794.

Unseen Histories

Many of the previous Indigenous visitors - the Ra’iatean Mai in 1774, the Cherokee Ostenaco in 1762 and the four supposed Iroquois in 1710 – were invited into high society in London. Did this happen with Bennelong too?

Kate Fullagar

No, it did not. But as I say above, this was not a pre-ordained failure. I argue that Phillip assumed an audience with King George III was likely because we see that he arranged for extremely expensive clothing for Bennelong, and that he set him upon an itinerary around London which had been followed by earlier Indigenous treaty-signers.

Phillip was a student of eighteenth-century British imperial protocols, and knew what had always happened before. The fact that Phillip’s superiors – the Secretary of State and others – decided against such a meeting in the 1790s speaks of a change in imperial practice around this time. The British government was discovering that without any European rivals in New South Wales, and with an Indigenous population now severely compromised by smallpox and violence, they might not need to follow the international legal code that had dictated their behaviour around the world until now.

Unseen Histories

Was there any lasting impact from this visit? Did it shape British attitudes towards the place that was soon to be called ‘Australia’?

Kate Fullagar

Without a treaty, the visit had much less impact than it might have had. In fact the distinct lack of impact summarises in a way the British government’s attitude to New South Wales for a good long while afterwards – the colony was expected to take care of itself while British forces were focused on repressing French revolutionary spread until at least 1815.

By the time that Britain looked again at the potential of New South Wales to consolidate its power in the southern hemisphere, the Indigenous population had suffered further displacement, making them less and less a problem in European eyes.

Unseen Histories

You argue that both Phillip and Bennelong’s reputations – one as a paragon of Enlightenment, the other as an emblem of loss – are being contested today. Can you tell us a little about this?

Kate Fullagar

After my version of this tale of imperial intrusion, you can discern my attitude towards so-called Enlightenment. Well, actually I do confirm that Phillip was an ideal man of the Enlightenment, but I work to show that British Enlightenment in this era was limited by its imperial imperatives, its acceptance of slavery, and its approval of dispossession.

Phillip should remind us that Australia was not founded in ideals about humanity, equality, and so on (common words used to describe Phillip and, by association, the best of New South Wales). It was rather set up to further the aims of an escalating world power that established still-unmet legacies of theft and coercion.

Bennelong did not die a broken man; he just died having turned his back on colonial culture, which to colonists could only suggest tragedy. Today that image of Bennelong is slowly changing, as we confront the scattered evidence of Indigenous esteem for the man that has been hiding in plain sight. Hopefully this changed image will one day also change how we think about what Bennelong has always symbolised – the future of Aboriginal political agency in a settler regime.

The resounding defeat on 14 October 2023 of the recent referendum for an Indigenous Voice to the Australian Parliament indicates that this day is still some way off 𖡹

Bennelong and Phillip: A History Unravelled

Simon & Schuster Australia (eBook edition), 4 October, 2023

RRP: £8.74

"At a moment of profound uncertainty for future relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, Bennelong and Phillip is essential reading"

– Mark McKenna, author of Return to Uluru

The first joint biography of Bennelong and Governor Arthur Phillip, two pivotal figures in Australian history – the colonised and coloniser – and a bold and innovative new portrait of both.

Bennelong and Phillip were leaders of their two sides in the first encounters between Britain and Indigenous Australians, Phillip the colony’s first governor, and Bennelong the Yiyura leader. The pair have come to represent the conflict that flared and has never settled.

Fullagar’s account is also the first full biography of Bennelong of any kind and it challenges many misconceptions, among them that he became alienated from his people and that Phillip was a paragon of Enlightenment benevolence. It tells the story of the men’s marriages, including Bennelong’s best-known wife, Barangaroo, and Phillip’s unusual domestic arrangements, and places the period in the context of the Aboriginal world and the demands of empire.

To present this history afresh, Bennelong & Phillip relates events in reverse, moving beyond the limitations of typical Western ways of writing about the past, which have long privileged the coloniser over the colonised. Bennelong’s world was hardly linear at all, and in Fullagar’s approach his and Phillip’s histories now share an equally unfamiliar framing.

"Kate Fullagar has achieved something astonishing … This is reconciled history at its very best"

– Professor Lynette Russell AM

"With insight and empathy, Kate Fullagar adds new depth and meaning to this old story of nation-building and imperial dispossession"

– Bill Gammage AM, author of The Biggest Estate on Earth

With thanks to Anna O'Grady