Cherry the Pioneering Dog

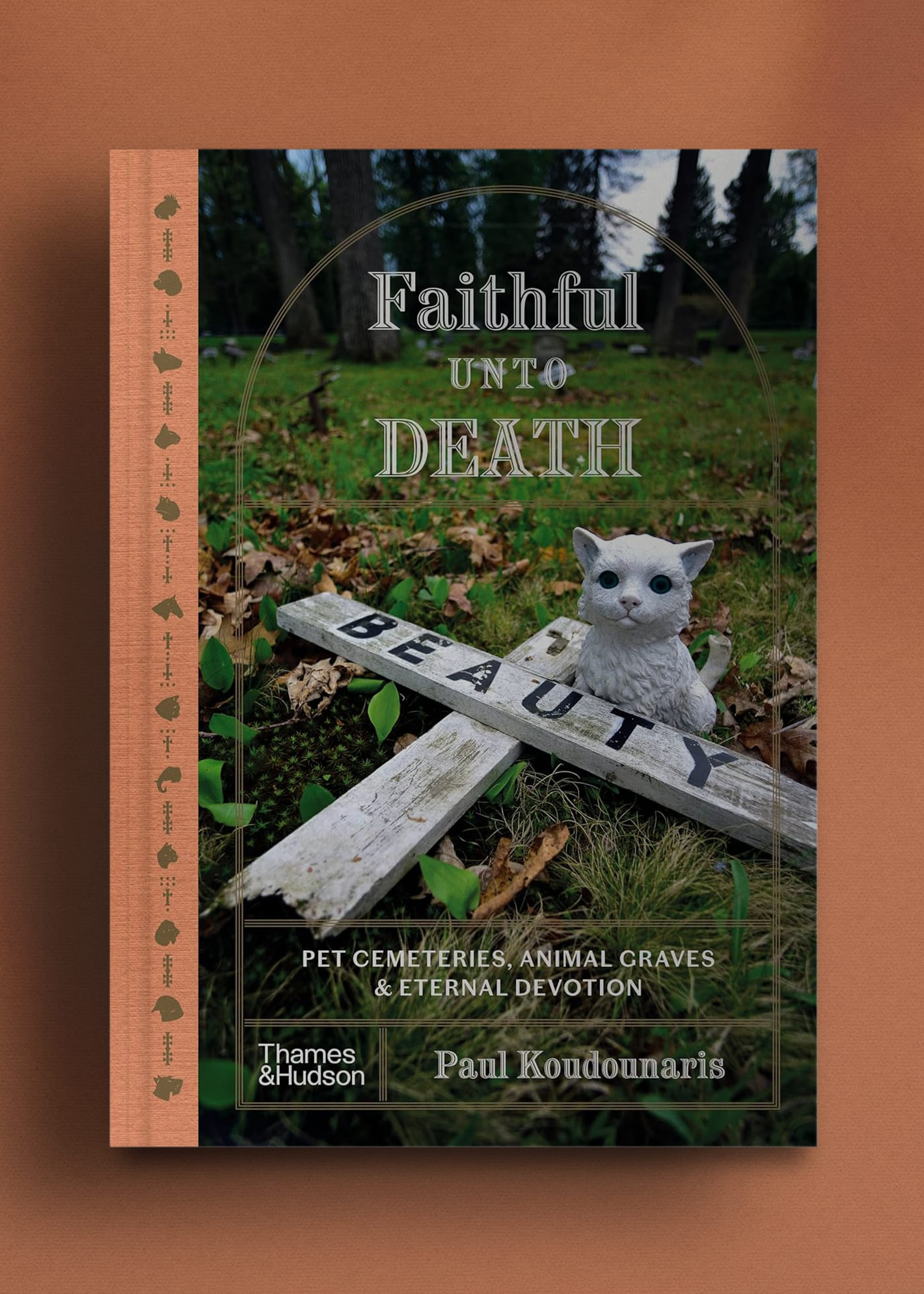

In this excerpt from 'Faithful Unto Death', Paul Koudounaris traces the modern tradition of pet commemoration back to its roots in Victorian England

The death of a favourite pet is an event many families have to confront. In 1881 the trauma was experienced by the Lewis-Barned family of London when their Maltese dog 'Cherry' passed away.

Out of this rather commonplace sadness rose an extraordinary new tradition.

As Paul Koudounaris explains in his new book, Faithful Unto Death, the events that followed Cherry's death marked a significant moment of social change.

Excerpted from Paul Koudounaris Faithful Unto Death. For full references and notes please consult the published book.

Cherry was a good dog. A playful Maltese who wanted to be involved in anything and everything his family did, he was always the first to run downstairs to fetch the mail when it arrived at their home at 10 Cambridge Square in London.

Scurrying back up the steps, he would deliver the letters to his mum, Emily Lewis-Barned, his tail wagging wildly as he anticipated his reward, the smile on her face as she reached down to pet him.

And if her door was closed, he would push them under and then wait for her to come out. When visitors stopped by, he delighted in being the centre of attention, playing soldier in a miniature army coat and helmet.

But his greatest joy was the children, Amelia and Harry. He treasured the walks they would take to Hyde Park, where they could play together in the soft grass on warm summer days.

Having lived a long and happy life, Cherry succumbed to old age in 1881. Tragic as the loss was for the Lewis-Barneds, there is, in and of itself, nothing remarkable in Cherry’s story. His canine virtues notwithstanding, there have always been plenty of dogs like him—those that live for love, and whose passing rends the heart and leaves in its wake a trail of tears.

Cherry would not ordinarily be remembered almost a century and a half later. His place in history was secured not through being a good dog, but rather as a consequence of a decision made upon his death.

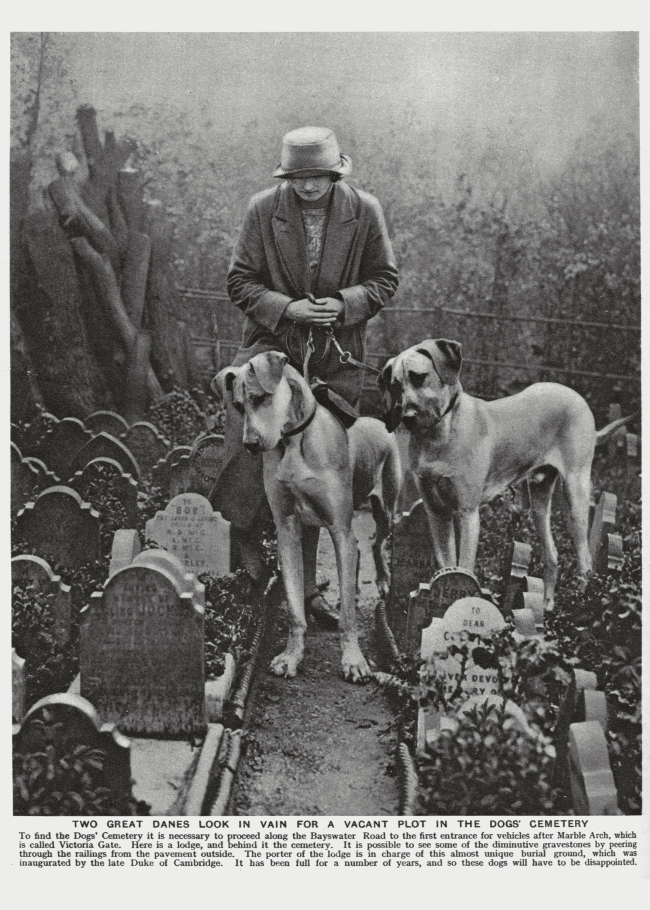

The trips to Hyde Park were frequent enough that the family had become friendly with the gatekeeper, Mr. Winbridge, who lived in a cottage behind Victoria Gate. To outsiders he seemed an intimidating figure, tall in stature, with a thick gray beard, and a uniform of red waistcoat and tall hat trimmed in gold. But to those who knew him, he was a most amiable fellow, a man who always offered a good word and kept a ready supply of lollipops on hand for the local children.

At a loss for a way to memorialize Cherry, the Lewis-Barneds approached Mr. Winbridge with a request. Could they lay him to rest in the garden of the gatekeeper’s cottage, just a stone’s throw from the lawn that had been the little dog’s favourite playground?

Mr. Winbridge agreed. A grave was dug, a funeral held, and a small headstone set in place, inscribed with the words:

Poor Cherry. Died 28 April 1881.

No one could have guessed that Cherry’s burial, a gesture of love on the part of his family and one of charity on the part of the gatekeeper, would turn out to be a revolutionary act. But as word spread that Cherry had been given a grave in the gatekeeper’s yard, it wasn’t long before other grieving pet owners began begging the same favour.

Mr. Winbridge was of too great a heart to say no, and slowly his little plot was transformed into something that not only London, but also the entire Western world, had been unaware that it desperately needed. His garden became the first urban cemetery for pets.

There was, of course, nothing revolutionary about burying an animal. Entire animal necropoli had existed in the ancient world. Bubastis in Egypt comes to mind, the city of cats, where the ground was filled with feline mummies. There had been individual burials of famous animals too, such as Alexander the Great’s favourite hunting dog, Peritas, given a grave at the gates of a town in India named in his honour.

Some ancient gravestones still survive, such as a Roman plaque dated to the second century CE, showing a dog of indeterminate breed standing under a temple pediment, and bearing the inscription, 'Helena, foster daughter, incomparable praiseworthy soul.'

We would err greatly, however, if we were to consider the necropolis at Bubastis as equal to a modern pet cemetery, or the grave markers for Helena, Stuczel, and Fortunatis to be evidence that ancient Rome or Baroque Germany had practices of pet ownership similar to ours.

The vast majority of the animals found in Egyptian necropoli were raised by temples specifically to be sacrificed, and as for the individual grave markers, they are exceptional specifically because they are so rare.

This is not to imply that the ancients were incapable of loving their animals as much as we are. Indeed, there is proof that many did. But our pets are of a different breed than their animal ancestors. They are a culturally specific phenomenon that pervades all levels of society, and we might argue that they do not truly qualify as animals at all, at least not in the minds of the people with whom they live.

They exist in a kind of liminal space, remaining in body a member of the species to which they were born, but taking on a role that is nearly human in the lives of those who love them.

Pets as we know them are an invention of the nineteenth century, a product of the great social shift that saw people flock to big cities in the wake of the Industrial Revolution.

Paris, for example, added nearly two and a quarter million people, while Greater London swelled by more than five million. New York City, meanwhile, grew from sixty thousand residents to three and a half million, an astounding increase of almost sixtyfold.

Rural traditions of animal husbandry had no place in congested cities, but that didn’t mean the new arrivals ceased to keep animals. There was an evolution in their relationship, however, as the cramped quarters of the modern metropolis drew people and animals closer than they had ever been, and not just physically, but emotionally.

Not only were people bonding with animals in an entirely new way, the vast panoply of cruelty to which they had been subjected for millennia was more on display than ever before—and becoming increasingly intolerable to wide swathes of the public.

The nineteenth century gave birth to welfare organizations, starting in England in 1824 with the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Such groups attempted to stop the heinous abuses suffered by animals as a source of cheap labour, and the victims were more than just stereotypical beasts of burden: even dogs and cats might be worked to death.

The new movement stressed that they are sentient beings, and that cruelty towards them was a sign of degraded moral sensibility. Showing kindness to animals, on the other hand, was promoted as a virtue, and one that brought great rewards.

If we could understand their emotions, it was conjectured, it might help us establish meaningful attachments that could in turn make our own lives richer. This all seems self-evident now, but these were entirely new ideas at the time.

The Italian Money Men, 1922. This photograph captures much of the twentieth century financial world; a world that Nogara charted so well. (⇲ Public Domain) Photograph The Agence Rol Collection

In the United States, Charles Burden brought a suit against a neighbour in Johnson County, Missouri, who had shot his favorite dog, Drum, in 1869.

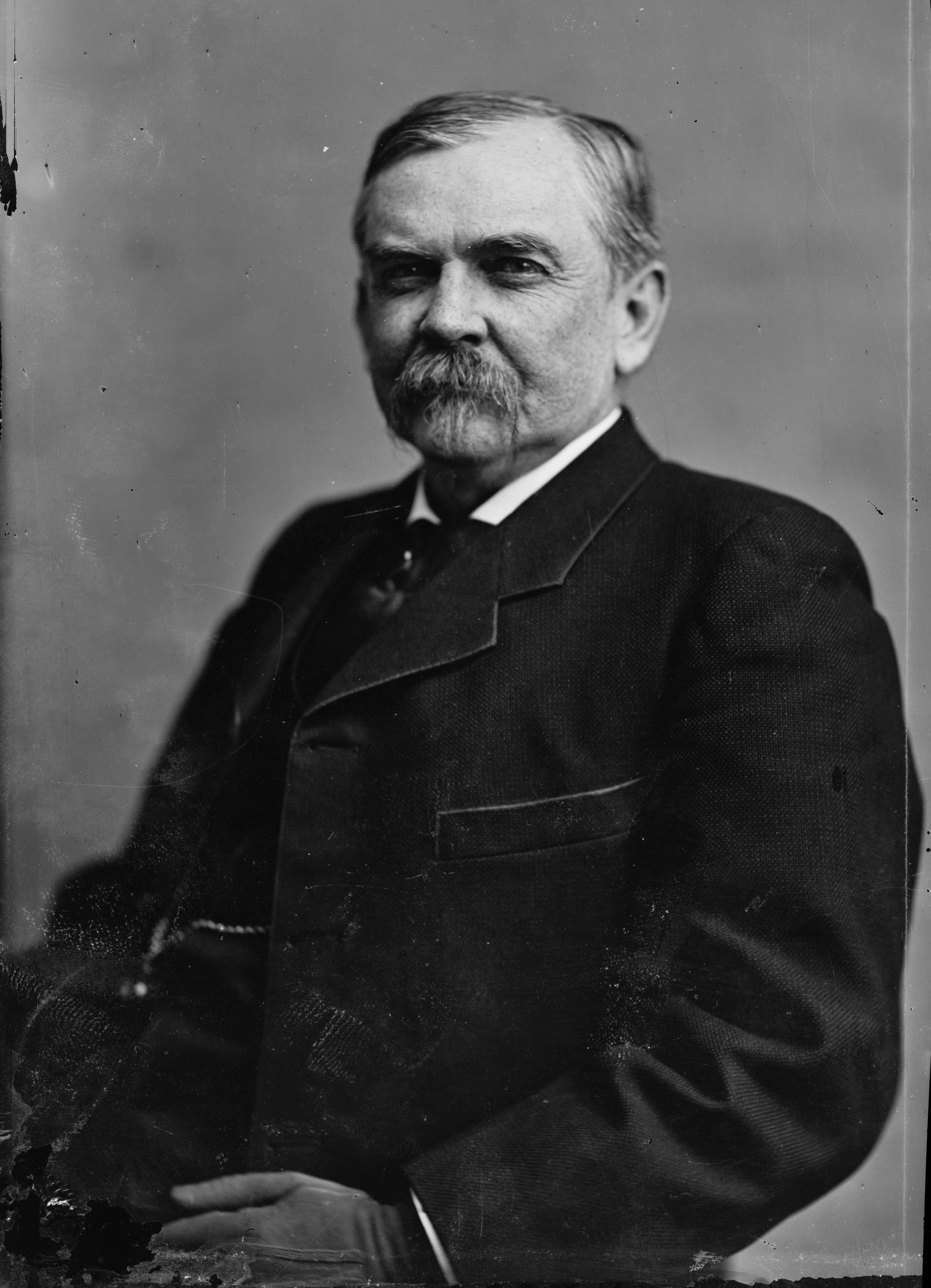

Taking such a matter to court was odd enough, but Burden was suing not just for the replacement value of his hound. In addition, he wanted damages for what he had lost: the love and affection of an animal companion. The matter seemed laughable until George Vest, a Missouri senator and himself a dog lover, addressed the jury with one of the great orations in American legal history.

'The one absolutely unselfish friend that a man can have ... the one that never proves ungrateful or treacherous, is his dog,' Vest began.

Senator George Graham Vest

A man’s dog stands by him in prosperity and in poverty, in health and in sickness. He will sleep on the cold ground, where the wintry winds blow and the snow drives fiercely, if only he may be near his master’s side.

He will kiss the hand that has no food to offer, he will lick the wounds and sores that come in encounters with the roughness of the world ...

When all other friends desert, he remains ... and when the last scene of all comes, and death takes the master in its embrace and his body is laid away in the cold ground ... there by his graveside will the noble dog be found, his head between his paws, his eyes sad but open in alert watchfulness, faithful and true even to death.

Vest drew tears from those assembled, and won Burden’s case. He also gave birth to a popular new phrase: 'A dog is man’s best friend.'

It was a precedent-seting victory, the first time in history a court of law had affirmed that an animal’s worth is more than just material ■

Paul Koudounaris has a doctorate in Art History from the University of California and has written widely on European ossuaries and charnel houses for both academic and popular journals.

Among his books are Heavenly Bodies: Cult Treasures & Spectacular Saints from the Catacombs and The Empire of Death: A Cultural History of Ossuaries and Charnel Houses.

Faithful Unto Death: Pet Cemeteries, Animal Graves and Eternal Devotion

Thames & Hudson, 19 September, 2024

RRP: £25 | 256 pages | ISBN: 978-0500027516

The remarkable stories of beloved pets – from the famous and unusual to the everyday – memorialized at burial sites around the world, accompanied by a rich selection of archival photos and the author’s evocative images of their final resting places.

When a little dog named Cherry died in 1881, his owners arranged for a grave in a nearby gatekeeper’s garden in London. At this time, the idea that a pet, even one that had lived as a family member, might be given a dignified burial was considered comical. But when other pet owners, likewise determined to memorialize their companion animals, followed suit, the world’s first urban pet cemetery was born.

More soon followed across Europe, the United States, and then the rest of the world, resulting in a revolution in the way we consider animals. Faithful Unto Death tells the stories of people who gave their hearts to a disparate variety of species, yet were all united in one common belief: that the reward at death for a faithful animal companion should reflect the love it offered during life.

Losing a pet has always been a unique kind of pain. No set rituals exist to help provide closure when pets die, there are no readily shared passages from spiritual texts, no community of compassion to surround the mourner and help alleviate grief. And there is a sense of taboo, that it is somehow socially incorrect to mourn an animal as one would a person and feel the pain so intensely. Faithful Unto Death confronts this taboo by telling the stories of people who have memorialized their beloved animals.

"A poignant and moving celebration of mankind’s animal companions that is sure to touch the hearts of anyone who reads it. Koudounaris reminds us that grief can cross the boundaries of species, and that the pain we suffer when a beloved pet dies is equal to the love we shared while they were alive" – Lindsey Fitzharris, author of The Facemaker

Additional Credit

With thanks to Caitlin Kirkman