D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four

Nineteen historians tell the story of Operation Overlord, or D-Day, in forty-four images

Operation Overlord commenced in the early hours of 6 June 1944, a date that has forever afterwards been remembered as 'D-Day'.

Within a year of D-Day western Europe would be liberated, Nazi Germany would be defeated and Adolf Hitler would be dead.

We asked nineteen expert historians to tell the story of Operation Overlord through forty-four specially selected images.

With contributions from Mark Barnes, Greg Baughen, Ian Baxter, Taylor Downing, Stephen Fisher, Helen Fry, Peter Gibbs, Garrett M. Graff, Nick Hewitt, Tony Holmes, Damien Lewis, Jordan J. Lloyd, Peter Moore, Clare Mulley, John Henry Phillips, Anthony Tucker-Jones, Julie Wheelwright, Christian Wolmar and Stephen Wright.

With curated and remastered images from the public archives by Jordan J. Lloyd

In the dark days of 1940, when it seemed as likely as not that Britain would succumb to the frightful power of the Nazi war machine, the prospect of a counter invasion of continental Europe was remote.

But after the opening of an eastern front in June 1941 and the entry of the United States of America into the war in December of that year, the Nazi hold on western Europe became far more precarious.

In the months and years that followed, the chances of an Allied invasion increased. A day of reckoning, it was clear to everyone, was approaching.

1/44

14 January 1943: The Casablanca Conference

Taylor Downing: The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and President Franklin Roosevelt got on wonderfully well in the warm sunshine of Casablanca for the famous Conference in January 1943. Of the many major decisions reached, the most momentous was the commitment to go ahead with an invasion of northern Europe sometime in spring 1944.

The photo records smiles all round but the conference revealed deep divisions between the US and British chiefs of staff. The American position was to start organising an invasion as soon as possible, preferably for 1943. The British argued that with no aerial supremacy and with the U-boats still powerful in the Atlantic, a cross-Channel invasion could be suicidal and the Allies should concentrate on the Mediterranean theatre. General Alan Brooke recorded days of bitter arguments between the two staffs in his diary. But neither side wanted to go back to their political leaders and report an impasse.

So, eventually a compromise was reached to start planning for 1944. Consequently, everyone looks happy.

2/44

April 1943: Operation Mincemeat

Helen Fry: In April 1943, long before the eventual invasion, British intelligence launched a major deception plan, codenamed Operation Mincemeat.

A dead body of ‘Major Martin’ in the uniform of the Royal Marines was floated off the coast of Spain, carrying fake invasion plans. It was planned by Section 17M of Naval Intelligence that had fourteen members, two-thirds of whom were women.

The Germans fell for the ruse and believed an invasion was about to happen in Greece and Sardinia, rather than Sicily. An appendix to a report on the operation ended with the words: ‘MINCEMEAT swallowed whole.’ Due to its success, it was believed possible to wrong foot the Germans again immediately ahead of D-Day in new deceptions under the umbrella of Operation Bodyguard. Deception was vital to protect D-Day and it led to German troops being held back in other areas of France; consequently, reducing the Allied losses and casualties during the landings.

3/44

Early 1944: World War 2 in the North Sea area

Peter Moore: This map was issued by the US Navy in the months before Operation Overlord. A stylish piece of political cartography, it related a rousing story about the Battle of the Atlantic with the tagline, ‘Our Navy Breaks The U-Boat Scourge On The Allies’ Supply Lines With Destroyers, Destroyer Escorts and Escort Carriers'.

To take a step backwards, however, is to see the broader narrative embedded within the artwork. Britain is presented as the crucible of power. Aircraft fly sorties over the Channel to France and, in greater numbers, they cross the North Sea to bomb the industrial towns of the Third Reich.

This map, which would have been displayed in soldiers’ barracks as a motivational device, engages with the idea that was gathering force in the early months of 1944. An invasion was coming. As a reporter for the New York Times described it, England had become a great warehouse full of equipment labelled “Europe.”’

4/44

1 February 1944: invasion planning

Mark Barnes: This photograph shows the famous gathering of Operation Overlord top brass presented to the press at the headquarters of SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) at Norfolk House, London, on 1 February 1944.

General Dwight Eisenhower of the United States Army had arrived in London several weeks earlier to take command of what he would term the 'great crusade'. Initial planning for the invasion had begun in 1943, but the scale of intended operations had grown significantly under the auspices of British General Sir Bernard Montgomery in his role as land forces commander.

The men consented to pose sitting around a long table and as a group behind a desk. Each photographer managed to take three or four images. The expressions on the faces of some of the group betray a mixture of irritation and boredom; especially Deputy Supreme Commander Tedder, who seems to find it all a bit of a chore.

5/44

May 1944: Addressing the Royal Ulster Rifles in Hampshire

Peter Moore: Here General Sir Bernard Montgomery, who was appointed to lead all the land forces in Operation Overlord, can be seen speaking to the soldiers of the Royal Ulster Rifles from an improvised platform on the bonnet of a jeep. The force of Montgomery's personality can be gauged by total attention he commands.

Montgomery would later reflect on the importance of such informal meetings:

'When we were at home I had my British Army [and] the Canadian Army, and all the Americans, about two million, I went home, from the Eighth Army, and nobody knew me. And the soldiers said: 'Who is this guy Montgomery? We have heard of some chap in the desert who wears a beret with two badges on it, let us have a look at him'.

I knew this, so I decided, having formed the plan and got it working — got it going — I left it entirely to my staff. And I travelled England and Scotland, showing, talking to the soldiers, and I would talk to twenty thousand at one go. I would go and talk to them, from, standing on the bonnet of a jeep, with a loudspeaker, and then I would say, 'Now, come round me closer. Let's have a look at each other.'

They would all rush forward, and obviously, the general was swamped, but they liked it. And I think I can say that no man went across to Normandy who hadn't seen me and heard me speak.

I hoped, of course, I hoped that they would approve. Perhaps it was rather too much to hope. Anyhow I think they did approve really, in the end. They said, 'This guy looks alright'. They hadn't done any fighting, you see. They knew I had. They knew as far as battle was concerned, you see, I knew my stuff.' — Bernard Montgomery

6/44

15 May 1944: The Thunderclap Conference, St Paul's School

Peter Moore: As 6 June approached, the moment came for the secret military plans to be explained to the political and military establishments. In early May around 150 gilt edged invitations were sent to leading politicians and members of all the branches of the military. Each of the recipients were invited to attend a meeting at St Paul's School on Hammersmith, which is pictured in the photograph above.

15 May was a cold day for this unusual society event. In the front row sat Churchill and King George VI among a host of other dignitaries. Montgomery, who had been a pupil at the school many decades before, addressed his audience with the same blend of passion and conviction that he had perfected while speaking to the soldiers. He ran through every element of Operation Overlord as he expected it to play out.

The effect was powerful. King George — not a man given to public speaking — rose unprompted at the end and proclaimed the plans 'a wonderful undertaking'.

This meeting came to be known as the 'Thunderclap Conference'. It was significant for its subject matter, but also for the unique group of individuals it brought together. On 16 July 1944, just two months later, a German V-1 flying bomb landed just yards from St Paul's School, destroying the neighbouring St Mary's Church. Had such a strike occurred a little earlier, a dreadful calamity would have resulted.

7/44

May 1944: German coastal defences

Ian Baxter: This photograph shows a German infantryman emerging from one of their fortified dugouts near positions overlooking the Channel coast between St Martin de Varreville and Azeville in Normandy.

This area would soon be known as Utah Beach by American forces belonging to the US VII Corps. Facing the invading Allied forces were two German battalions of the 919th Grenadier Regiment, which were part of the 709th Static Infantry Division. Although a high percentage of these static coastal truppen had hardly any combat experience, for a number of months prior to Operation Overlord, the soldiers were put through rigorous defence drills.

Many were trained with artillery, anti-tank, and machine gun exercises, while others remained on constant observational duties. On 6 June 1944 the 709th were heavily engaged defending the coastal area against the US 4th Infantry Division.

8/44

19 May 1944: pre-invasion bombing

Stephen Fisher: Allied bombs fall over Ouistreham in Normandy. Although many targets on the beaches were attacked, preparatory bombing was carried out all along the French coast, so as not to make the landing area obvious to German intelligence.

Bombing Ouistreham was not without its risks. The lock gates at the mouth of the Caen Canal in Sword Area had been identified as a site of high importance. Control of the locks after D-Day would allow Allied vessels access to Ouistreham’s small port and to Caen docks, which would greatly help with the provision of supplies in the coming Normandy Campaign.

Fortunately the locks were not the target of these bombs, which instead are falling towards the neighbouring German coastal battery (codenamed 'Bass' by the Allies). The regular bombing eventually persuaded the Germans to withdraw the six 155mm guns from the battery until new enclosed casemates had been constructed to protect them. When 4 Commando attacked the site on D-Day they found that the gun pits were empty.

9/44

20 May 1944: dummy tank

Taylor Downing: The crew of a real US Army Sherman look in amazement as they pass a dummy tank. These dummy tanks were produced in large numbers to be observed and photographed from the air by enemy reconnaissance aircraft. Often lined up in vast assembly areas, the dummies helped convince enemy intelligence that there were more armoured units available than there were in reality.

They were designed in Britain largely by film technicians who were used to creating totally artificial backdrops that looked real on camera. The designers, set builders and carpenters from Shepperton Studios to the west of London came up with many designs that were simple and cheap to produce but looked like the real thing from 20,000 feet.

The tanks were often made of rubber or canvas around a simple metal frame and could be inflated in about 20 minutes. They were light and could be carried by four men, whereas the real thing could weigh up to 30 tonnes! The dummy tanks were used extensively in Operation Fortitude, the great deception operation around D-Day.

10/44

Early June 1944: James Stagg

Peter Moore: The portrait above shows Group Captain James Stagg, who had been appointed chief meteorologist to SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) at the end of 1943. As D-Day approached, Stagg was to become a critical figure.

By 1944 more than eight decades had passed since the Meteorological (Met) Office had issued their very first predictions of weather for the day ahead. But no particular forecast in those years could compete in gravity with that which confronted Stagg in the first week of June.

The day for the landings had long been fixed for 5 June. That date would bring a full moon with its accompanying low tide and it was hoped that the first week of the meteorological summer would bring calm seas and settled skies. These would provide the ideal conditions for an amphibious assault.

To Stagg's consternation and general alarm of everyone involved in the planning of Operation Overlord, the weather in early June was deeply unsettled. With the huge mass of soldiers, support teams and equipment assembled on the south coast, Stagg was confronted with one of the great dilemmas in the history of science. Should he be the person to prevent the invasion from going ahead?

11/44

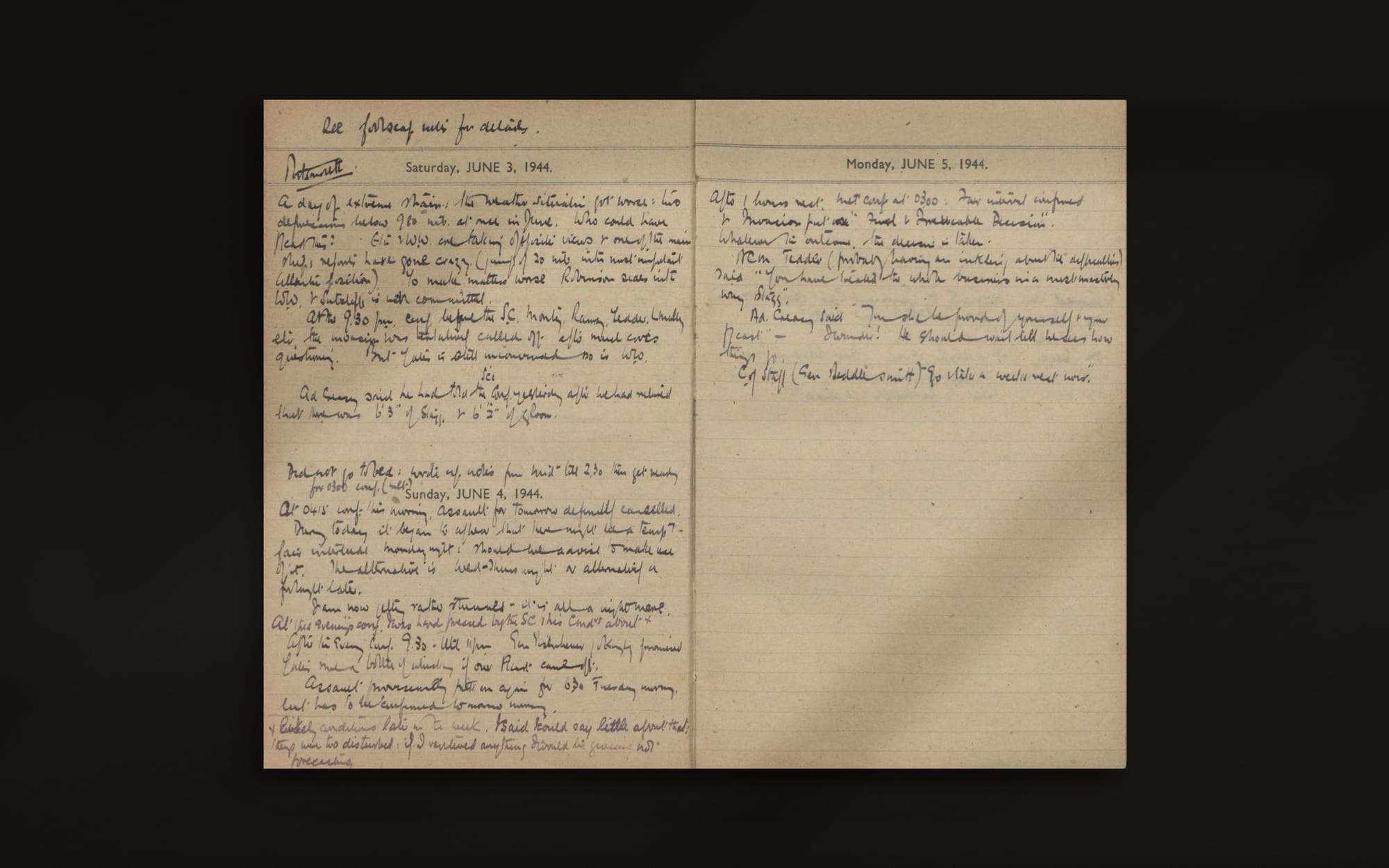

3-5 June 1944: extracts from James Stagg's diary

Saturday 3 June 1944

A day of extreme strain: the weather situation got worse: two depressions below 980mb at once in June. Who could have forecast this?

Eta [Air Ministry Weather Central] and W.W. [WideWing – the US Meteorological team] are taking opposite views and one of the main ships reports have gone crazy (jump of 20mb into most important Atlantic position) to make matters worse Robinson sides with W.W and Sutcliffe is non committal

At the 9.30 p.m. conf. before the S.C. [Eisenhower , 'Supreme Commander'] Monty, Ramsey, Tedder, Leigh- Mallory etc. the invasion was tentatively called off after much cross questioning. But Yates is still unconvinced so is W.W.

Sunday 4 June 1944

At 0415 conf[erence] this morning, Assault for tomorrow definitely cancelled.

During today it began to appear that there might be a temporary fair interval Monday night: should we advise to make use of it. The alternative is Wed-Thurs night or alternatively a fortnight later.

I am now getting rather stunned – it is all a nightmare.

At this evenings conf I was hard pressed by the SC and his Commanders about * After the evening Conf 9.30 – until 11pm Gen Eisenhower jokingly promised Yates and me a bottle of whiskey if our forecast came off.

Assault provisionally put on again for 6.30 Tuesday morning but has to be confirmed tomorrow morning. likely conditions later in the week. I said I could say little about that.

Monday 5 June 1944

After 1 hours rest Met Conf at 0300: Fair interval confirmed and Invasion put on ‘Final and Irrevocable Decision’. Whatever the outcome the decision is taken.

ACM Tedder (probably having an inkling about the difficulties) said ‘You have treated the whole business in a most masterly way Stagg.'

Ad. Creasy said 'You should be proud of yourself and your forecast' – I wonder. He should wait till he sees how things go.

12/44

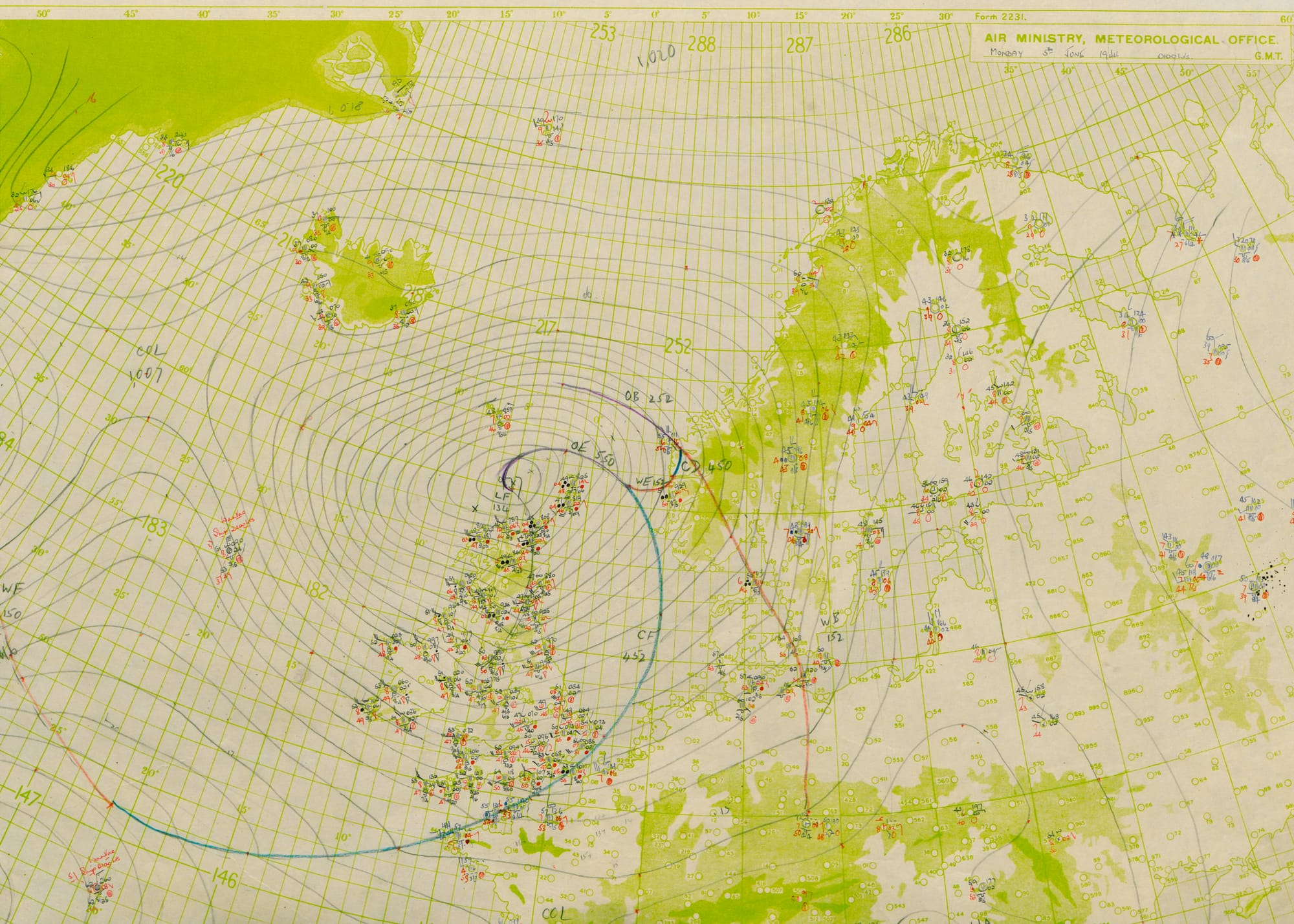

5 June 1944: A BBC Weather forecaster reflects on the dilemma

Peter Gibbs: I feel an immediate connection to the meteorologists who drew up this chart from 5 June 1944. As a forecaster starting my career 40 years after Stagg I was drawing those same pencil lines around hand-plotted inked observations decoded from a teleprinter printout.

What you need as a weather forecaster is an ability to analyse the weather upstream of your area of interest, so it's the observations in the direction the weather is coming from, in this case the west, which are the really important ones. That big hole in information over occupied Europe looks alarming at first sight, but it doesn't actually hamper the process too much. That's the weather that's already been and gone.

The thing that ramps up the stress, makes this such a tough call, is that all the predicted weather factors (wind speed, wave height, visibility, cloud cover) are right on the specified go/no go limits for the air and sea operations. It's every forecaster's nightmare. Just a small error in predicting the speed of movement, position and intensity of the area of low pressure to the north of Scotland and the transient ridge of high pressure following in from the Atlantic will tighten up or ease the isobars and tip the balance either way. It is an incredibly difficult call.

It would be so much simpler if there was a big, obvious storm barrelling in from the west — 'Sorry General, no go'. Or a big fat anticyclone sitting happily over southern England and the Channel — 'Yes General, green light'. But no, it's right on the cusp.

13/44

5 June 1944: James Rudder's Rangers

Mark Barnes: Men of Lieutenant Colonel James E Rudder's 2nd Ranger Battalion march along the seafront at Weymouth, having travelled a few miles from their staging area at Broadmayne.

These soldiers were sent to scale the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc in Normandy. The aim was to neutralise a German artillery battery that had guns ranging along Utah Beach. Rudder had convinced superiors that a direct assault by troops was the only way to ensure the guns would be destroyed. To add insult to injury, the guns had been moved some distance away but they were found and either destroyed or disabled by patrols of rangers sent out from Pointe du Hoc.

The assault would prove costly in terms of casualties. It gave Rudder and his men, however, a hallowed place in D-Day mythology. The remains of casemates and other fortifications at the site are a much visited attraction for Normandy pilgrims today.

14/44

5 June 1944: The Staging Grounds

Peter Moore: The scores of soldiers in this photograph, all of them busy and filled with nervous anticipation for what lay ahead, suggest the human scale of Operation Overlord.

Never before in British history had there been such a dramatic influx of outsiders. Beginning in January 1942, American military personnel had started to arrive at ports like Portsmouth and Liverpool. As the months and years passed their numbers rose with increasing rapidity. By the eve of the invasion in May 1944, about 1.6 million GIs were stationed in Britain.

With them the soldiers brought a new level of racial (there were 130,000 black troops) and cultural diversity to Britain. The troops were very young too, with most of them aged beneath twenty-five. These youthful GIs — chewing gum, with their generous chocolate rations, 'overpaid, oversexed and over here' —would leave an enduring impression on many Britons, along with an estimated 9,000 babies.

15/44

5 June 1944: The SAS and Operation Lost

Damien Lewis: In the hours prior to D-Day, one squadron of Special Air Service warriors parachuted into Brittany, north west France, charged to spread chaos and mayhem behind enemy lines.

So successful were they, the Germans sent thousands of troops to hunt them down. After an epic battle, that entire SAS squadron went silent - reported as 'missing in action' (MIA). Hence SAS Major Oswald Cary-Elwes, who is pictured above with his ever-faithful batman, Corporal Eric Mills, were parachuted into Brittany on the aptly named Operation Lost on 22 June, to track down and discover the fate of the missing squadron.

Over the coming days they did just that and were handed maps and reports revealing the enemy strengths and defences at St Malo, the key port on the Brittany coast. As Allied commanders were planning a Second D-Day — a landing directly into a port like St Malo — Cary-Elwes and Mills were ordered to slip the enemy net, to bring that priceless intelligence back to British shores.

So began one of the most epic escape and evasions of WWII.

16/44

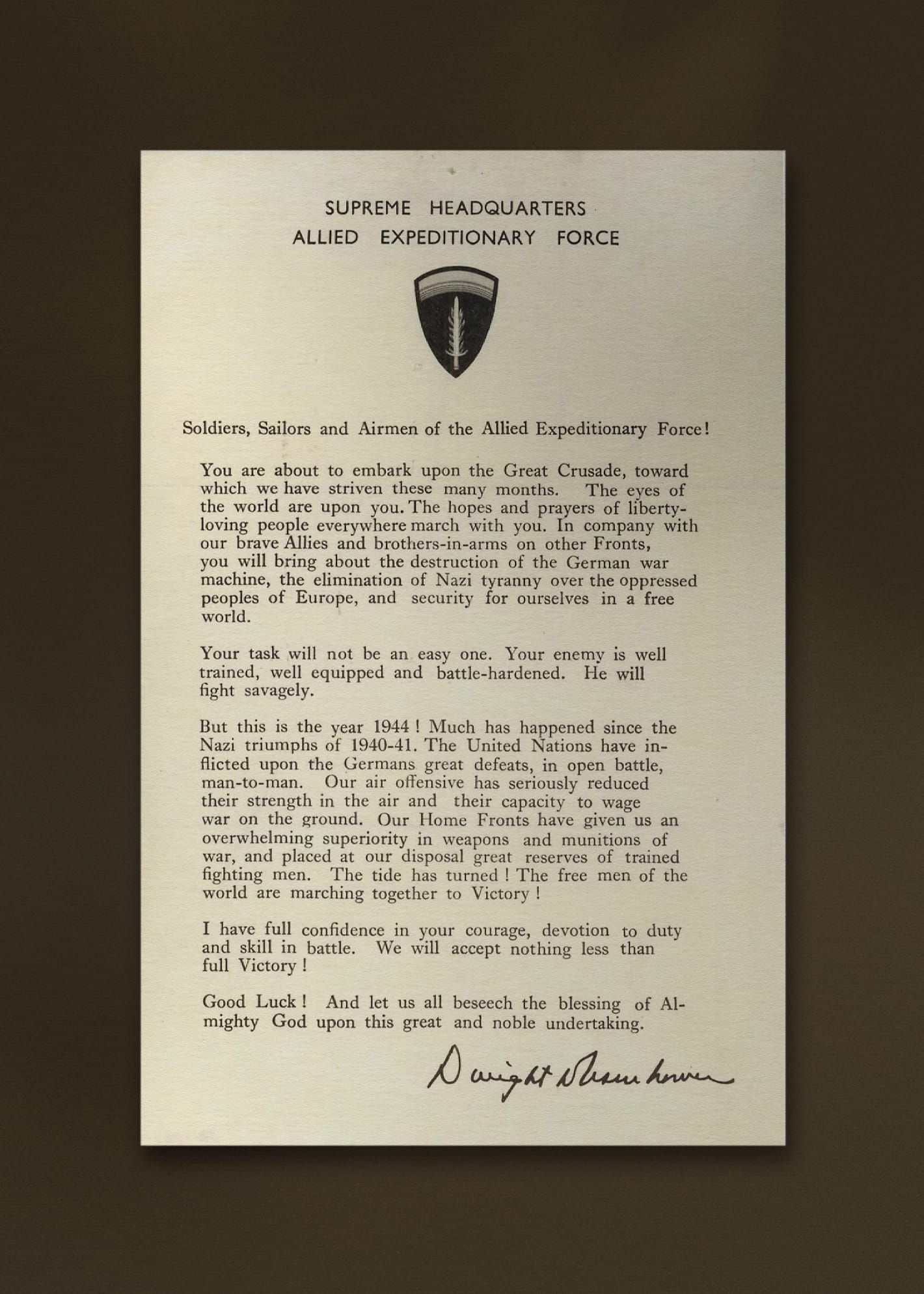

5 June 1944, 1800 hrs: Order of the Day

Jordan J. Lloyd: On the eve of the fifth, General Eisenhower’s 'Order of the Day' was distributed to 175,000 members of the Allied Expeditionary Force. It emphasised the invasion’s vital importance, calling it a ‘Great Crusade ... to bring about the destruction of the German war machine.’ The Supreme Headquarters would ‘accept nothing less than full victory’, a promise Eisenhower pre-recorded for radio broadcast after the attack had begun.

What is less known is Eisenhower’s other note, which was drafted for release in the event that the invasion stalled. This ran, ‘Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops’. In this draft Eisenhower took personal responsibility for the outcome, replacing the phrase ‘This particular operation’, with the following explanation:

‘My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.’

In his haste, Eisenhower mistakenly dated the note 5 July.

17/44

5 June 1944, 2030 hrs: the eyes of the world are upon you

Jordan J. Lloyd: General Eisenhower meets troopers of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment on the eve of the invasion. ‘Ike’, as Eisenhower was known, is captured conversing with 1st Lieutenant Wallace C. Strobel on his 22nd birthday. The 23 sign around Strobel's neck marks him out as 'jumpmaster' of plane #23.

In Strobel's own words: ‘We had darkened our faces and hands with burned cork, cocoa and cooking oil to be able to blend into the darkness and prevent reflection from the moon ... As [Eisenhower] came toward our group we straightened up and suddenly he came directly toward me ... he asked my name and which state I was from. I gave him my name and that I was from Michigan. He then said, “Oh yes, Michigan’s great fishing there. Been there several times and like it.”’

Eisenhower would later tell his chauffeur Kay Summersby, ‘It’s very hard to look a soldier in the eye, when you fear that you are sending him to his death.’ Strobel was one of nearly 800 soldiers jumping into Normandy. Only 129 survived in the hours and days which followed, though Strobel would live to the age of 77.

This photograph is colorized by Jordan J. Lloyd from an original black and white photograph.

After the twenty-four hour delay due to bad weather, acting on Group Captain Stagg's forecast, the invasion finally began at dawn on 6 June.

This date has frequently been described by historians as one of the most significant of the whole Second World War. For the political and military leaders the morning of 6 June was a time of intolerable tension.

A few months earlier the landings at Anzio in Italy had been difficult. Other amphibious assaults at Salerno and in Sicily had met with stern resistance. For Churchill himself, there was the haunting memory of Gallipoli in the First World War.

As the sun rose on a murky June morning, the Allied forces advanced towards the concrete architecture and barbed wire of the Nazi Atlantic Wall.

18/44

6 June 1944, D-Day: invasion routes

Jordan J. Lloyd: Initiating history’s largest amphibious assault was a mind-boggling logistical challenge, fraught with complications. In order to prepare for the ground assault, Allied paratroopers parachuted into Normandy from midnight to secure the exit points and key objectives. Throughout the night, deception ploys and aerial bombardments were initiated to compromise German defences.

By dawn, a colossal fleet with over a thousand warships drawn from eight different navies grouped together in the English Channel, heading towards their designated stretches of coastline. These were code-named: Utah, Omaha, Sword, Juno and Gold sectors. Their goal? To overwhelm German coastal defences and establish a vital beachhead for the Allied Expeditionary Force to liberate France and, from there, the rest of Western Europe.

Troops from the VII Corps and V Corps of the United States Army were tasked with securing Utah and Omaha Beaches respectively. Further east in the British and Canadian Zones, the Second Army contingent of 83,000 men were assigned to Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches.

The Allied Expeditionary Force would face fierce resistance from the Germans, with four and a half thousand deaths and 10,000 casualties on the first day alone.

19/44

6 June 1944c.0129 hrs: See You in Berlin

Jordan J. Lloyd: Frank D. Griffin (left) and Robert ‘Smokey’ J. Noody (right) of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, prepare for take-off in a Douglas C-47 from RAF Upottery in East Devon, England. They would be some of the first American soldiers to land on French soil as part of Mission Albany: a night time parachute assault with the objective to secure causeway exits at Utah Beach, in addition to other key targets; and to disrupt German communications.

Noody’s 2nd Battalion was flown in one of 81 C-47 transports taking off from East Devon, heading for their designated Drop Zone C, near Sainte Marie-du-Mont at 0120 hrs as part of a second wave.

Poor weather and German antiaircraft fire caused much of 2nd Battalion to jump further west, landing around Sainte Mère Église four miles away at the edge of the 101st Division’s objective area. Noody himself landed behind the mayor’s house, and days after, would use the pictured bazooka to destroy a German tank at Carentan.

The intense shot of Noody clutching Eisenhower’s order of the day, weighed down by his M-1 rifle, bazooka, three rockets, land mines and fifty feet of rope would be first published in Army Air Forces Magazine.

Noody passed away in 2020, survived by his wife Elizabeth, who had no inkling of her husband's wartime exploits until she saw the photograph some time later.

20/44

6 June 1944, 0230 hrs: the Bassingbourn Airmen

Tony Holmes: Crammed into the mission briefing hut at RAF Bassingbourn, aircrew from the 91st Bombardment Group (BG), dubbed 'The Ragged Irregulars', listen intently to the instructions being given to them in the pre-dawn hours of 6 June 1944.

Their missions that day would be governed by strict — and unique — rules, with aircrew told 'Guns will be manned but not test-fired at any time. Gunners will not fire at any airplane at any time unless being attacked. Bombing of primary targets will be carried out within time limits prescribed, otherwise secondary or last resort targets will be bombed. No second runs will be accomplished according to schedule — regardless.'

Just six B-17G Flying Fortresses participated in the first D-Day raid undertaken by the 91st BG, the aircraft taking off before dawn to hit coastal gun batteries. The poor weather conditions that had blighted Normandy for the previous four days persisted on the 6th, forcing crews to rely on Pathfinders when it came to bombing the target.

The following two missions flown by the group were also weather affected, resulting in most aircrew involved being left bitterly disappointed when cloud cover blocked their views of the invasion beaches. On a more positive note, no Flak or fighters were encountered.

21/44

6 June 1944, 0600 hrs: the Juggernaut

Anthony Tucker-Jones: One of the key factors to the success of Operation Overlordwas the Allied Expeditionary Air Force comprising the RAF 2nd Tactical Air Force and the US 9th Air Force. This was commanded by Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory who had led RAF 12 Group during the Battle of Britain.

In the run up to D-Day the AEAF’s job was to attack German defences, lines of communication, radar and V-1 flying bomb launch sites. On D-Day it pounded Hitler’s so-called Atlantic Wall and provided close air support for the assault troops. The Luftwaffe proved a no show with just two fighters briefly strafing Juno and Sword Beaches.

A sign of the technological advances that were to come was the enormous Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bomber. This was the largest single-engine fighter of the Second World War. This extremely rugged aircraft could take a lot of punishment and was dubbed the ‘Juggernaut’ or ‘Jug’ by its pilots.

It flew alongside the North American P-51 Mustang fighter and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning long-range fighter on escort duties and was also employed as a fighter-bomber. Shortly after D-Day P-47s were involved in aerial combat fending off Luftwaffe fighter attacks on Allied shipping.

22/44

6 June 1944, c. 0700 hrs: French Coast Dead Ahead

Garrett M. Graff: These lightweight Higgins Boats, named after their New Orleans manufacturer and known as LCVPs to the military, Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel, carried roughly a platoon of soldiers each and ferried tens of thousands of troops ashore on D-Day.

As this photo shows, the ride to shore for many soldiers — which was often two to four hours long — was so turbulent and storm-tossed that it caused violent seasickness. Pfc. John Robertson, of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division recalled, 'Most of my boat team was seasick. I remember heaving over the side, and someone said, 'Get your head down! You’ll get killed!' I said: 'I’m dying anyway!''

23/44

6 June 1944, c. 0730 hrs: First Wave

Peter Moore: This dramatic photograph captures a decisive moment of encounter. Taken from one of the U.S Coast Guard landing barges that ferried troops to the beaches, it shows the atmosphere of a dark and threatening morning.

Clouds hang low. Smoke rises from the beaches. The sea is unsettled and it is further disturbed by the LCVP Higgins boats that hasten towards the shore. In the cold shallows dozens of American soldiers splash towards the land, holding their weapons across their chests.

Frank Joseph DeVita, Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class in the U.S. Coast Guard experienced D-Day in a similar manner to this photographer. His mission had begun at four in the morning. DeVita's Higgins Boat transported the soldiers the final eleven miles to the coast (the German guns had a range of ten miles) and they had to navigate through waters strewn with mines and obstacles called Belgian Gates. From the beach MG42 machine guns fired 1200 rounds per minute towards them, which bounced off the ramp ‘like firecrackers’.

DeVita’s job was to drop the ramp and when he reluctantly did so 15 or 16 GIs were killed instantly. ‘We were all scared’ he wrote. ‘It was terrible — the best word is pandemonium’.

24/44

6 June 1944, c. 0740 hrs: Into the Jaws of Death

Garrett M. Graff: This photo, known as Into the Jaws of Death takes its title from Tennyson’s famous poem Charge of the Light Brigade, and was captured by a Coast Guard photograph Robert F. Sargent as troops from Company E, 16th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division landed on Omaha Beach about an hour into the opening of D-Day.

The plywood and metal Higgins Boats, like the one at the foreground of the picture, landed Company E right amid some of the heaviest fighting on the beach that day, nearly directly in front of the so-called Colleville Draw and in the face of two German 'resistance nests.'

In the distance, you can see the looming cliffs behind Omaha Beach and the smoke already obscuring the beach from grass fires ignited by allied bombers and naval artillery.

25/44

6 June 1944, c. 0800 hrs: Horsa

Stephen Wright: These guys are standing in front of a British Airspeed AS 51 assault glider, known as the ‘Horsa’. The black and white stripes on the fuselage and the lower surface of the wing are a new addition. Following the disaster during the Sicily Invasion in 1943, when Allied shipping fired on their own aircraft, the decision was made to paint identification stripes, as shown and also on the upper surface of the wings, on all aircraft participating in the Normandy Invasion.

The star replaced the RAF ‘roundel’ on American Horsas. The passenger entrance/exit has a sliding door which can just be seen. In front of the other wing, as part of the main cargo door, is another sliding door. The main spar, the part that connects the wings, comes down into the passenger/cargo compartment; the men will be saved from having to duck by boarding in two sections, rear and forward.

Their expressions say it all about what is to come. This will be their Longest Day, so far.

26/44

6 June 1944: LCH 185

John Henry Phillips: LCH 185, which is pictured above, began life as a Landing Craft Infantry (Large). By 1944, it had seen action at the invasions of Sicily and Italy, where this photo was taken. In the build-up to D-Day, 185 was converted into a Landing Craft Headquarters, filled with radio equipment and experts trained to operate it. It was assigned to lead Force S at Sword Beach.

As a headquarters craft, 185 had both high-ranking men on board who were in charge of various aspects of the landing. There were also others like Patrick Thomas and Jack Barringer, two telegraphists who had become best friends in the months leading up to the invasion.

As the French coast came closer on 6 June, they were both amazed by the peaceful sight of two houses glistening in the morning sun. Jack noticed the stillness in the air until the naval guns opened up. He was shocked by the sight. Shells were everywhere. The bombardment shook everything in its wake.

‘Just about did a little piece,’ Jack wrote to his brother afterwards. As German machine-gun bullets rattled against the hull of 185, Patrick and Jack tried to ignore the noise to relay crucial messages across Force S, just as they had done countless times before during rehearsals in the rough seas off the Scottish Coast.

LCH 185 survived the first wave and guided in those that followed. It stayed in the water off Sword Beach for two weeks as part of the Trout Line, before an acoustic mine sent it to the bottom of the English Channel. At least 35 men on board died, and less than ten survived. Only four bodies were ever recovered.

As 185 sank, Patrick, floating in the water, could see Jack nearby. He was badly wounded and desperately searching for a lifebelt amongst the chaos. Patrick went to throw one to his best friend, but another wounded man nearby began to grab at it.

Knowing the weight of two men would pull them both down, Patrick let the second man have the lifebelt, and Jack disappeared beneath the waves. He is buried at Ranville Cemetery. Patrick visited his friend's grave for the first time 70 years later.

27/44

6 June 1944, 0840 hrs: Lord Lovat

Stephen Fisher: The 1st Special Service Brigade landed with 3rd British Infantry Division in Sword area on D-Day. The first commandos to come ashore on Queen Red were 4 Commando, with two troops of French commandos under Commandant Kieffer.

Their mission was to strike left and neutralise a gun battery in Ouistreham, a task they had completed by noon. Landing behind them came brigade commander Brigadier the Lord Lovat.

On board Landing Craft Infantry (Small) 519, Lieutenant Commander Rupert Curtis led 11 more LCI(S) towards the beach, and nosed his vessel onto the shore at approximately 08:40, just to the east of the main German strongpoint on Queen Red Beach. Stood at the bow, Lord Lovat impatiently waited for naval ratings to push the ramps down into the sea and then led his men into the surf.

Captain Evans of the Army Film and Photographic Unit captured the moment that Lovat’s personal piper, Bill Millin, got to the top of the ramp. Lovat has been identified as the man stood in the water just to the right of a line of his men (although how this identification has been made is lost to the sands of time).

Once ashore, led by 6 Commando, 1st Special Service Brigade pushed inland towards Pegasus Bridge. Crossing the Caen Canal and River Orne sometime after noon, they pressed on to reinforce the bridgehead on Breville Ridge, where they would hold the line for several months.

28/44

6 June 1944, 0900 hrs: Utah Beach from Above

Tony Holmes: Although the medium bomber crews of the Ninth Air Force were not specifically tasked with taking photographs of the invasion beaches on 6 June, 1944, a number of stunning images like this one were taken from A-20 Havocs and B-26 Marauders.

According to the official caption that was printed on the back of this 8 x 10 photograph issued to the Press just hours after the first American troops had come ashore at Utah Beach, 'This is how the beaches of Normandy looked on D-Day from one of the Ninth Air Force Marauder medium bombers which went out in close support of Allied ground troops. Bombing from lower-than-usual altitudes, the Marauders struck behind the enemy lines at gun positions, troop and tank concentrations and vital road and rail junctions. Bomber crews came back with descriptions of ‘a Channel filled with every kind of ship ever built’ and beaches as crowded as ‘Fifth Avenue.’

This photograph was taken from one of 320 medium bombers that hit seven targets on Utah Beach from H-Hour minus 30 minutes on the morning of 6 June 1944. Beginning at 0517 hrs, single squadrons of A-20s and B-26s based at airfields in southern England commenced flying a relay system of strikes on specific targets. By the end of the ‘Longest Day’, the Havocs and Marauders had contributed more than 1000 sorties to the 4656 flown by all elements of the Ninth Air Force.

29/44

6 June 1944, 1030 hrs: Sword Beach from Above

Stephen Fisher: As landing craft surged ashore on D-Day, dozens of F-4 Lightning photo reconnaissance aircraft surveyed the scene from above, capturing the landings in amazing detail.

Here the pilot is flying west along Queen White Beach in Sword Sector, overlooking the westernmost end of the landing area. From other photographs in the same sequence it is possible to tell from the fall of shadows that the time is approximately 10:30, and by studying Force S’s fleet orders and reports we can identify the vessels on the beach.

The three Landing Craft Tank, vessels with a large open tank deck to carry armour and vehicles, are part of 43 LCT Flotilla, who first landed at approximately 09:25 with vehicles of 8 Infantry Brigade (the assault brigade). But their landing was hampered by the rapidly rising tide that had already narrowed the beach to less than 50 metres.

Enemy mortar fire further complicated the landing and more than an hour later, some of the LCT are still trying to unload onto a congested beach. Next to them are two Landing Craft Infantry (Large) of 263 LCI(L) Flotilla, who carried infantry of 185 Brigade and similarly found their landing area blocked by traffic. And worse is to follow — coming in behind them are the first landing craft of 40 LCT Flotilla, carrying some 70 tanks of the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

The congestion on Sword Beach made it difficult for the units to press inland. The Staffordshire Yeomanry’s advance was delayed, but fortuitously it meant they were in exactly the right place to repel a German armoured counterattack later in the afternoon.

30/44

6 June 1944, 1100 hrs: Fox Red

Jordan J. Lloyd: Taking shelter beneath the chalk cliffs, an American soldier is being treated by a 16th Infantry Regiment medic. This eastern stretch of Omaha Beach, code-named Fox Green and Fox Red, had some of the highest American attrition rates, owing to two German widerstandsnester ‘resistance nests’ flanking the American’s exit from the beach.

The fortified strongpoint WN62 contained a German MG 42 machine gun, which could hose down the invading force on the beach at a rate of 1,200 rounds per minute. Twenty-year old Private Heinrich Severloh, a farmer’s son from Baden-Württemburg would spend the following nine hours with a dozen men repelling the Allies from taking their objective. By the time Sgt. Richard Taylor of the US Signal Corps took this photograph, Severloh’s machine gun was the only operational weapon at the strongpoint.

In the end, American troops managed to scale the cliffs in order to capture the widerstandsnester’s adjacent to WN62 in the morning.

31/44

6 June 1944: The Fallen

Helen Fry: D-Day was a turning point in the Second World War and an essential invasion to end the Nazi occupation in Europe. It came at great cost in human life on both sides.

This image serves as a stark reminder of the ultimate sacrifice made by the Allied soldiers who fought and fell on that historic day; a day in which over four thousand four hundred soldiers lost their lives and over five thousand others were wounded. A lone helmet balanced upon a rifle stands as a makeshift memorial amid the destroyed landscape, symbolising the loss of young life.

Nearby, ammunition boxes lie open, a testament to the fierce battle that raged across the beaches immediately after the landings. Their courage and sacrifice forged a path towards victory but the cost of D-Day was steep. The legacy of the ultimate sacrifice they gave strongly endures over 80 years later. It is a legacy that must be remembered.

For all the immense challenges, D-Day had turned out to be an unquestionable success. But at sunset that evening, the Allies were left with the sobering reflection that all they had achieved so far was the merest toehold in a small part of one coastline of northern France. Another desperate phase of the war lay ahead.

Most pressingly of all the concerns was the prospect of a German counter offensive. The weeks that followed D-Day would see the start of the Battle of Normandy with great emphasis placed on the strategic city of Caen.

Of almost equal importance was the need to supply the colossal number of service personnel who were now on the ground in France. As a complex logistical plan whirred into action, teams of nurses were dispatched to care for the injured.

All this would have been challenging enough on its own, but the weather that had aggravated the Allies for weeks was about to become even worse.

32/44

9 June 1944: Panzer Division

Ian Baxter: Panzergrenadiers belonging to the Panzer-Lehr Division dismount in haste from an Sd.Kfz.251 armoured personnel carrier and go into action in the Caen sector on 9 June 1944.

The division was committed against British and Canadian forces and was placed on the front line adjacent to the 12th SS Panzer-Division `Hitlerjugend`. The following day the 21st Panzers also moved up and helped the other two divisions form the principal shield around Caen, with a thrown together number of other ad hoc units that had retreated from the coastal sector.

For the next days and weeks that followed the `Hitlerjugend`, `Lehr` division and the 21st Panzer carried on fighting stubbornly in and around the city of Caen, which was slowly being reduced to rubble. All day and night the fighting raged. Many soldiers were killed at point blank range, whilst others fighting in the hedgerows and ditches, fought to the death.

Through the lanes and farm tracks that criss-crossed the Normandy countryside, rows of dead from both sides lay sprawled out amid a mass of hand grenades and smashed and burnt out vehicles.

33/44

c. 12 June 1944: Battle of the Build-up

Nick Hewitt: Extraordinary activity on Omaha Beach in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, as the ‘Battle of the Build Up’ begins.

Reinforcing the Allied armies from the sea faster than the Germans could reinforce by land with the entire European road and rail network at their disposal was an extraordinary challenge. Ferry craft shuttle back and forth from freighters offshore, while Landing Ships (Tank) ‘dry out’ and unload on the beach.

The LSTs were intended to discharge their cargoes out at sea on to motorised rafts known as Rhino Ferries, as it was feared their backs would break if they were beached, but the process was too slow, the fears proved groundless and by D+1 they were routinely drying out. The barrage balloons flying above the fleet as a defence against low level air attack are a reminder that nobody took the absence of the Luftwaffe for granted in June 1944.

34/44

14 June 1944: The First Nurse on French Soil

Clare Mulley: Allied nurses served close to frontlines throughout the Second World War, sometimes weathering enemy fire, in field and evacuation hospitals, on hospital trains and as flight nurses on medical transport aircraft.

The first nurses arrived at Normandy on 10 June. Landing craft ferried them to the beachhead, from where they progressed to their forward nursing stations. 24-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Margaret Stanfill of the US Army Nurse Corps, who had already served in North Africa and Italy, was the first American nurse to set foot on French soil. This photograph shows her preparing dressings at a tented workstation on 14 June, at Carentan about three miles inland. She had set to work within three hours of reaching the French shore. In units besieged with patients, the highly trained nurses immediately started prioritising the most urgent cases, administering intravenous drips, oxygen and stomach pumps, changing bandages and giving shots.

One Scottish nurse, Phyllis Heninger, who landed around 18 June, recalled that although well supplied, conditions were inevitably basic with patients already being treated on the ground between the beds. Another abiding memory was how hungry she was, until the Americans, like Stanfill, shared their tins of spam and sausages. The Allied (and some enemy) wounded were shipped back to British coastal towns like Portsmouth, where lorries brought them to the civilian hospitals that had been cleared, scrubbed and supplied in advance.

After the war, Margaret Stanfill returned to her Texas home where she married an American veteran, Wilson ‘Wick’ Moore, and raised a family. She died, aged 86, in 2006.

35/44

14 June 1944: Screeching Rockets

Greg Baughen: Rocket-armed Typhoons proved to be the scourge of the German Army during the latter stages of the Normandy Campaign. The rockets were not particularly accurate, but they had an enormous effect on German morale. In the 1940 Battle of France it had been the wailing siren of the Stukas that was the defining sound of the campaign. In the 1944 Battle of France, it was the screeching rockets that left an indelible impression on the enemy.

But where were the Typhoons on D-Day? Nearly 15,000 sorties were flown by the Allied air forces but hardly any provided direct support for the troops on the ground. A massive naval and aerial bombardment preceded the landings but as the troops went ashore only a handful of Typhoons struck the formidable German defences that confronted them. For the rest of the day frustrated Typhoon pilots waited for orders that never came.

The Canadian and British troops attempting to reach Caen ran into stiff resistance but there was no air support to sweep the opposition aside in the way that the Desert Air Force had become so adept at doing in North Africa and Italy. In terms of close air support, it was not the British Armed Forces’ 'finest hour'!

36/44

June-August 1944: The Allied Nurses

Clare Mulley: On 7 August 1944, the hospital ship on which two British Queen Alexandra nurses, Dorothy Field, aged 32, and 27-year-old Molly Evershed, were serving, struck a mine off Juno beach. Reports were that the ship was almost cut in half and was quickly listing.

Described as practical, energetic women, as well as lively and always eager to help others, both women were strong swimmers, but Field and Evershed refused to leave their posts. Repeatedly returning below, they carried 75 stretcher-cases back up to deck and, with great difficulty, over the rails and into lifeboats. Field reached a lifeboat herself, but returned to help more men. The last reported sighting of Evershed was of her struggling to escape from a hatch as the ship went down.

Dorothy Field and Molly Evershed are the only female names on the Normandy Memorial to the 22,442 service personnel killed during the campaign. Both were also mentioned in Despatches, and were posthumously awarded the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct. After their deaths, their parents received 75 letters of thanks, one from each of the men whose lives they had saved.

37/44

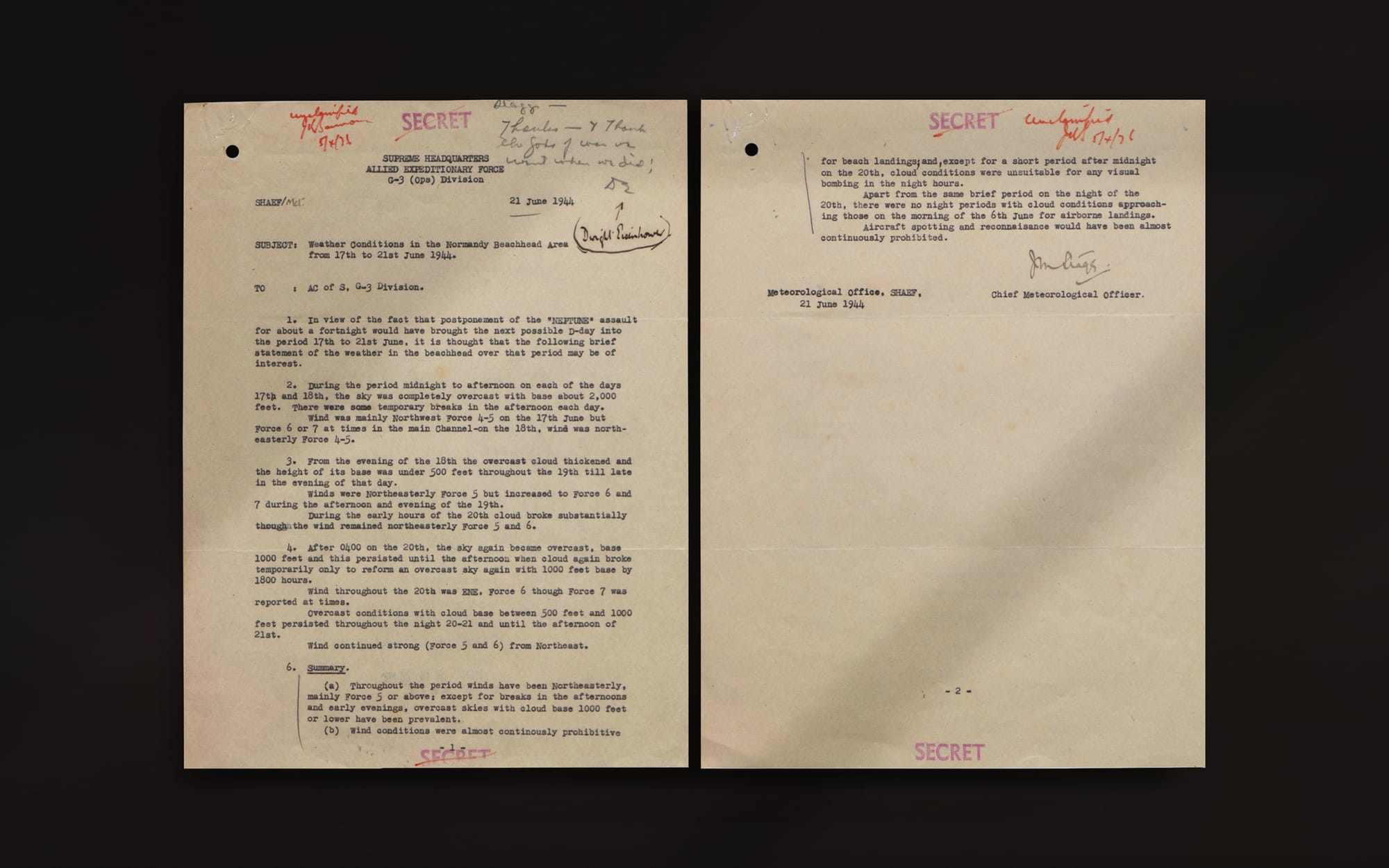

21 June 1944: Gods of War

Peter Moore: On 21 June James Stagg had the satisfaction of writing the above letter to his superiors. There had been thoughts, he reflected, when the storms of early June had disturbed the Channel, to postpone D-Day for a fortnight. This would have shifted the date of the invasion to somewhere between 17 — 21 June.

The conditions within this window, Stagg affirmed, began poorly and grew steadily worse. The cloud base had been thick, winds had gusted from the north east. On 19 June a vicious storm had swept the coast and the next day it was still gusting at as much as Force Seven on the Beaufort Scale, which meant winds of between 28 and 33 knots.

Stagg summarised his note. 'Wind conditions were almost continuously prohibitive for beach landings, and, except for a short period after midnight on the 20th, cloud conditions were unsuitable for any visual bombing in the night hours'.

38/44

21 June 1944: Riding the Storm

Nick Hewitt: On 19 June the worst summer storm in living memory swept through the assault area. For thirty-six hours, wave heights averaged eight feet, and unloading ceased. 800 landing craft were stranded, many badly damaged. The American artificial harbour, Mulberry A at St Laurent, was completely wrecked, and the British Mulberry B at Arromanches was damaged.

The image shows a dismal jumble of broken landing craft on Omaha Beach, including the Royal Navy’s LCT-2337 (right) which was a total loss, and the US Navy’s LCT-199 and LST-543 (centre, background). In the foreground is a Rhino Ferry and to the left, behind a smashed Higgins Boat, is the wreck of the US Coastguard’s LCI-92, which had been hit and set on fire on D-Day.

Thanks to the salvage teams, by 23 June the fleet was exceeding pre-storm rates of discharge, and by 8 July 600 of the wrecks had been refloated.

39/44

21 June 1944: Riding the Storm

Anthony Tucker-Jones: D-Day involved the appliance of science and an unprecedented level of problem solving. This included how best to land supplies in the invasion area. The answer was the construction of two Mulberry harbours, one to be assembled at Arromanches off Gold Beach and the other at St Laurent off Omaha Beach. The comprehensive design was agreed upon in the summer of 1943 and used two million tons of concrete and steel.

The first elements of the Mulberry harbours were shipped over to the Normandy coast on D-Day. Although not complete they were up and running six days later. All went well until 19 June when a massive storm blew up in the English Channel halting shipping and preventing further work.

After two days the American Mulberry at Omaha was smashed by the 30-knot gales and 8 foot waves. Its breakwater was overwhelmed and the piers and blockships destroyed. As a result it had to be written off. Despite this, by the end of June the Allies had landed 850,000 men, 570,000 tons of supplies and 149,000 vehicles.

Ironically the Americans ended up landing more per day over the open beaches than the British at Arromanches.

40/44

22 June 1944: Another View of the Mulberrys

Christian Wolmar: Operation Overlord was all about logistics and the carriage of supplies was on a far greater scale than the transport of men. Nearly everything needed by the invading forces, from arms and ammunition to food and clothing was taken over by ship but the delay in capturing and repairing the main port, Cherbourg, meant that shipping in the Channel was often forced to wait, as shown in this picture on 22 June.

The situation was partly relieved by the use of the Mulberry Harbour pre-built on Hayling Island near Portsmouth and towed across the Channel in a remarkable operation, but a second one intended for use by US forces was destroyed by a storm three days before this photograph was taken, delaying the landing of many vital supplies.

Fortunately, the allied control of the air was almost total which meant the barrage balloons shown in this picture were largely redundant. Eventually the capture of Cherbourg on 26 June relieved the pressure, though only three weeks later by which time the damage caused by the Germans had been restored.

41/44

3 July 1944: The WACO Glider

Stephen Wright: This photograph shows the two Allied assault glider stalwarts: on the left, and in the back, is the American CG-4A (‘CG’ for Cargo Glider) built by the Weaver Aircraft Company. Frequently referred to as the WACO, it could carry thirteen troops, or a field gun, or a jeep, or a trailer.

It was also used by the British Glider Pilot Regiment (GPR) (who nicknamed it ‘Hadrian’) in Sicily in 1943 and in several post-D-Day operations. On the right is the British Airspeed AS 51, or ‘Horsa’ to the GPR, and so to the Americans. Its usual troop only load was twenty-five. In cargo mode, amongst other configurations, it could carry a jeep and trailer and field gun and crew.

On a personal note, my British Glider Pilot uncle, who was killed on D-Day, ferried Horsas to RAF Fulbeck, home of the 434th Troop Carrier Group US 9th Air Force. The 434th flew Horsas from RAF Aldermaston on D-Day.

42/44

June-July 1944: The Liberation Line

Christian Wolmar: The railways were the key to ensuring a rapid advance after D-Day but they had been all but destroyed by a combination of Allied bombing and sabotage by the French Resistance.

Right from the early days of the invasion troops experienced in all aspects of repairing and operation railways were being shipped across the Channel, along with vast quantities of equipment including hundreds of locomotives and thousands of wagons. As shown in this picture, trucks and tanks were routinely carried by rail to save fuel and manpower, and in total more two thirds of the supplies landed at Cherbourg were taken forward towards the front on the newly reinstated railways.

Ultimately around 50,000 engineers worked on rebuilding and operating the lines, and without their efforts, the war would undoubtedly have been prolonged. Trucks were simply incapable of carrying out the task, as they needed far more manpower and fuel, and the roads were congested. Yet, the exploits of these railwaymen have been largely forgotten but are highlighted in The Liberation Line, the last untold story of the Normandy Landings published in 2024.

43/44

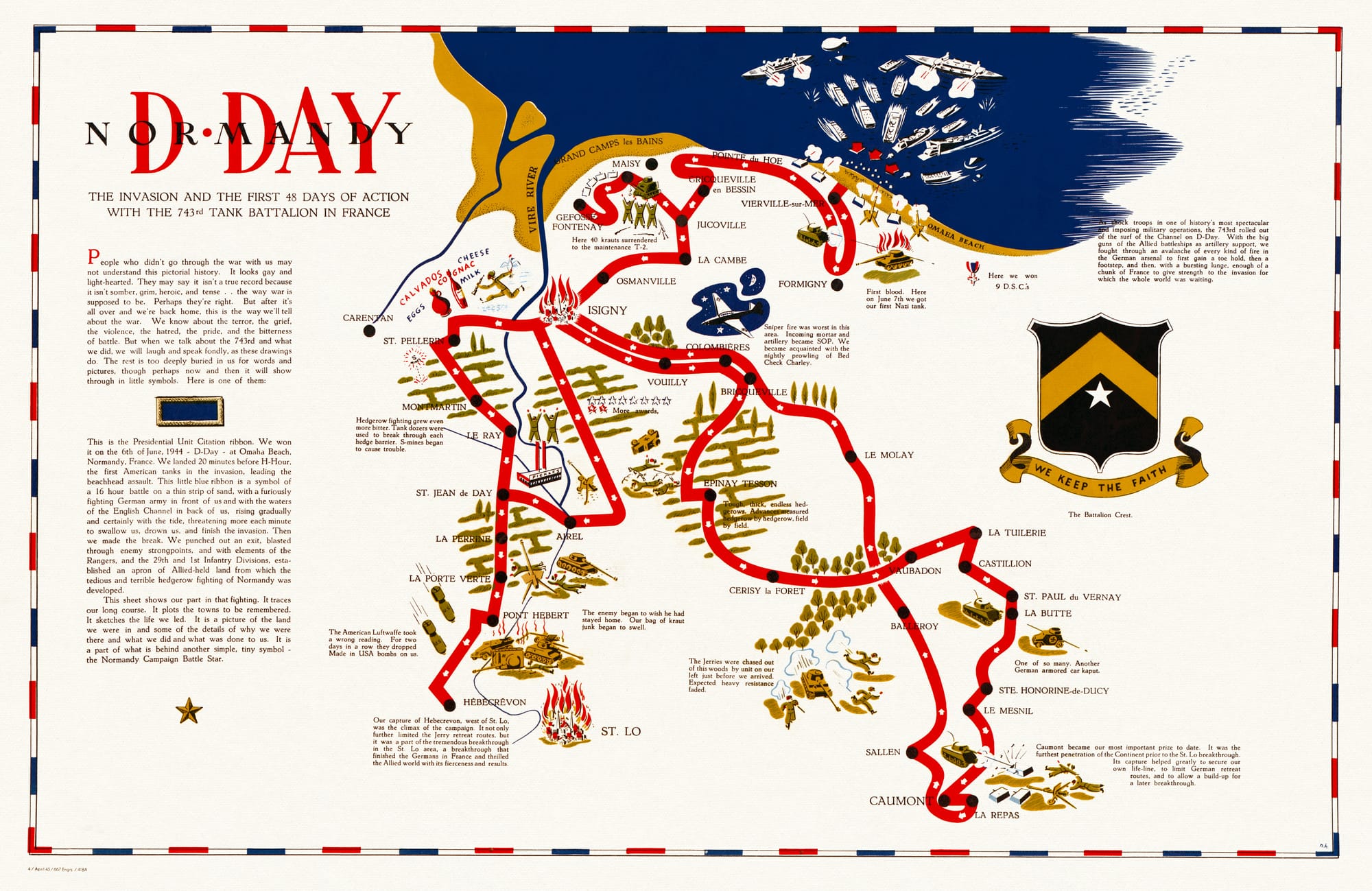

24 July 1944: The First 48 Days of Action

Peter Moore: As the Allies probed further away from the beaches and into the winding lanes and rolling hills of Normandy, the tank became an increasingly vital weapon. This brightly illustrated map shows the progress of a tank regiment, the 743 Battalion, as it fought its way forward through the countryside.

Engaged in a similar fashion were the Sherwood Rangers with their allocation of Sherman Tanks. In the latter part of June the Rangers were involved in several sharp engagements for the control of strategically important ridges. Of this desperate time one of its officers, Major John Semken, would later reflect:

‘[D-Day] was the easiest day of a ghastly battle when Normandy became a battle field and was converted into a charnel house for man and beast and when we left Normandy it was a horror. And of course that was only the beginning of the journey anyway, through Belgium, Holland and into Germany, a journey of a thousand miles, as the crow files, and of course marked all the way by the graves of young men.’

44/44

Commemorating D-Day

Julie Wheelwright: The image of Allied Service members, soberly remembering the fallen US Army veterans of the Picauville 90th Infantry Division, in 2015, reminds us of history’s vital function, not only as a memorial to heroic and terrible human behaviour, but as a warning for future generations.

For these servicemen and women it was their grandparents who, even if not directly involved in the conflict, still found their lives shaped by its outcomes. That generation often wished to forget its horrors, whether they had survived the D-Day landings, or had been stationed in another theatre of war where their mental and physical health was shattered or their families ripped apart. Many of them wanted to banish it from their thoughts and forge on with new lives.

Succeeding generations would take a different perspective. In Britain, the publication of post-war memoirs, the oral histories collected by bodies such as the National Sound Archives and the Imperial War Museum, the diaries of Mass Observation and the eventual release of key documents to the National Archives, have left a rich legacy of the Second World War’s complexity.

In these acts of commemoration, we reflect on epic moments of human tragedy. These moments, such as D-Day, resist easy mythologising and leave us seeking for a clearer understanding of the human devastation that war demands.

D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four was an ambitious endeavour to collate and publish in time for the 80th anniversary of D-Day and would simply not have been possible without the aid and expertise of our contributors.

We have created a list of their books on Bookshop.org, so please do give them your support. You can also support Unseen Histories by their purchasing books via the links, from which we will receive a small commission; or buy a collectible WW2 fine art print from the Unseen Histories web-store, hand-printed in England and individually finished with a monogram emboss.

Thank you very much for reading •

Special thanks to the many publicists and publishers who helped us contact our contributors.