D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four – The Invasion (Part 2 of 3)

In this special commemorative feature, nineteen historians tell the story of Operation Overlord, or D-Day, in forty-four images

Operation Overlord commenced in the early hours of 6 June 1944, a date that has forever afterwards been remembered as 'D-Day'.

Within a year of D-Day western Europe would be liberated, Nazi Germany would be defeated and Adolf Hitler would be dead.

In this three-part Viewfinder series, we asked nineteen expert historians to tell the story of Operation Overlord through forty-four specially selected images.

With contributions from Jordan Acosta, Mark Barnes, Greg Baughen, Ian Baxter, Taylor Downing, Stephen Fisher, Helen Fry, Peter Gibbs, Garrett M. Graff, Nick Hewitt, Tony Holmes, Damien Lewis, Peter Moore, Clare Mulley, John Henry Phillips, Anthony Tucker-Jones, Julie Wheelwright, Christian Wolmar and Stephen Wright

With curated and remastered images from the public archives by the Unseen Histories Studio

After the twenty-four hour delay due to bad weather, acting on Group Captain Stagg's forecast, the invasion finally began at dawn on 6 June.

This date has frequently been described by historians as one of the most significant of the whole Second World War. For the political and military leaders the morning of 6 June was a time of intolerable tension.

A few months earlier the landings at Anzio in Italy had been difficult. Other amphibious assaults at Salerno and in Sicily had met with stern resistance. For Churchill himself, there was the haunting memory of Gallipoli in the First World War.

As the sun rose on a murky June morning, the Allied forces advanced towards the concrete architecture and barbed wire of the Nazi Atlantic Wall.

18/44

6 June 1944, D-Day – Invasion routes

Jordan Acosta: Initiating history’s largest amphibious assault was a mind-boggling logistical challenge, fraught with complications. In order to prepare for the ground assault, Allied paratroopers parachuted into Normandy from midnight to secure the exit points and key objectives. Throughout the night, deception ploys and aerial bombardments were initiated to compromise German defences.

By dawn, a colossal fleet with over a thousand warships drawn from eight different navies grouped together in the English Channel, heading towards their designated stretches of coastline. These were code-named: Utah, Omaha, Sword, Juno and Gold sectors. Their goal? To overwhelm German coastal defences and establish a vital beachhead for the Allied Expeditionary Force to liberate France and, from there, the rest of Western Europe.

Troops from the VII Corps and V Corps of the United States Army were tasked with securing Utah and Omaha Beaches respectively. Further east in the British and Canadian Zones, the Second Army contingent of 83,000 men were assigned to Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches.

The Allied Expeditionary Force would face fierce resistance from the Germans, with four and a half thousand deaths and 10,000 casualties on the first day alone.

19/44

6 June 1944, 0129 hrs – See You in Berlin

Jordan Acosta: Frank D. Griffin (left) and Robert ‘Smokey’ J. Noody (right) of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, prepare for take-off in a Douglas C-47 from RAF Upottery in East Devon, England. They would be some of the first American soldiers to land on French soil as part of Mission Albany: a night time parachute assault with the objective to secure causeway exits at Utah Beach, in addition to other key targets; and to disrupt German communications.

Noody’s 2nd Battalion was flown in one of 81 C-47 transports taking off from East Devon, heading for their designated Drop Zone C, near Sainte Marie-du-Mont at 0120 hrs as part of a second wave.

Poor weather and German antiaircraft fire caused much of 2nd Battalion to jump further west, landing around Sainte Mère Église four miles away at the edge of the 101st Division’s objective area. Noody himself landed behind the mayor’s house, and days after, would use the pictured bazooka to destroy a German tank at Carentan.

The intense shot of Noody clutching Eisenhower’s order of the day, weighed down by his M-1 rifle, bazooka, three rockets, land mines and fifty feet of rope would be first published in Army Air Forces Magazine.

Noody passed away in 2020, survived by his wife Elizabeth, who had no inkling of her husband's wartime exploits until she saw the photograph some time later.

20/44

6 June 1944, 0230 hrs – The Bassingbourn airmen

Tony Holmes: Crammed into the mission briefing hut at RAF Bassingbourn, aircrew from the 91st Bombardment Group (BG), dubbed 'The Ragged Irregulars', listen intently to the instructions being given to them in the pre-dawn hours of 6 June 1944.

Their missions that day would be governed by strict — and unique — rules, with aircrew told 'Guns will be manned but not test-fired at any time. Gunners will not fire at any airplane at any time unless being attacked. Bombing of primary targets will be carried out within time limits prescribed, otherwise secondary or last resort targets will be bombed. No second runs will be accomplished according to schedule — regardless.'

Just six B-17G Flying Fortresses participated in the first D-Day raid undertaken by the 91st BG, the aircraft taking off before dawn to hit coastal gun batteries. The poor weather conditions that had blighted Normandy for the previous four days persisted on the 6th, forcing crews to rely on Pathfinders when it came to bombing the target.

The following two missions flown by the group were also weather affected, resulting in most aircrew involved being left bitterly disappointed when cloud cover blocked their views of the invasion beaches. On a more positive note, no Flak or fighters were encountered.

21/44

6 June 1944, 0600 hrs – The Juggernaut

Anthony Tucker-Jones: One of the key factors to the success of Operation Overlord was the Allied Expeditionary Air Force comprising the RAF 2nd Tactical Air Force and the US 9th Air Force. This was commanded by Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory who had led RAF 12 Group during the Battle of Britain.

In the run up to D-Day the AEAF’s job was to attack German defences, lines of communication, radar and V-1 flying bomb launch sites. On D-Day it pounded Hitler’s so-called Atlantic Wall and provided close air support for the assault troops. The Luftwaffe proved a no show with just two fighters briefly strafing Juno and Sword Beaches.

A sign of the technological advances that were to come was the enormous Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bomber. This was the largest single-engine fighter of the Second World War. This extremely rugged aircraft could take a lot of punishment and was dubbed the ‘Juggernaut’ or ‘Jug’ by its pilots.

It flew alongside the North American P-51 Mustang fighter and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning long-range fighter on escort duties and was also employed as a fighter-bomber. Shortly after D-Day P-47s were involved in aerial combat fending off Luftwaffe fighter attacks on Allied shipping.

22/44

6 June 1944, c. 0700 hrs – French coast dead ahead

Garrett M. Graff: These lightweight Higgins Boats, named after their New Orleans manufacturer and known as LCVPs to the military, Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel, carried roughly a platoon of soldiers each and ferried tens of thousands of troops ashore on D-Day.

As this photo shows, the ride to shore for many soldiers — which was often two to four hours long — was so turbulent and storm-tossed that it caused violent seasickness. Pfc. John Robertson, of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division recalled, 'Most of my boat team was seasick. I remember heaving over the side, and someone said, 'Get your head down! You’ll get killed!' I said: 'I’m dying anyway!'

23/44

6 June 1944, c. 0730 hrs – First wave

Peter Moore: This dramatic photograph captures a decisive moment of encounter. Taken from one of the U.S Coast Guard landing barges that ferried troops to the beaches, it shows the atmosphere of a dark and threatening morning.

Clouds hang low. Smoke rises from the beaches. The sea is unsettled and it is further disturbed by the LCVP Higgins boats that hasten towards the shore. In the cold shallows dozens of American soldiers splash towards the land, holding their weapons across their chests.

Frank Joseph DeVita, Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class in the U.S. Coast Guard experienced D-Day in a similar manner to this photographer. His mission had begun at four in the morning. DeVita's Higgins Boat transported the soldiers the final eleven miles to the coast (the German guns had a range of ten miles) and they had to navigate through waters strewn with mines and obstacles called Belgian Gates. From the beach MG42 machine guns fired 1200 rounds per minute towards them, which bounced off the ramp ‘like firecrackers’.

DeVita’s job was to drop the ramp and when he reluctantly did so 15 or 16 GIs were killed instantly. ‘We were all scared’ he wrote. ‘It was terrible — the best word is pandemonium’.

24/44

6 June 1944, c. 0740 hrs – Into the Jaws of Death

Garrett M. Graff: This photo, known as Into the Jaws of Death takes its title from Tennyson’s famous poem Charge of the Light Brigade, and was captured by a Coast Guard photographer Robert F. Sargent as troops from Company E, 16th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division landed on Omaha Beach about an hour into the opening of D-Day.

The plywood and metal Higgins Boats, like the one at the foreground of the picture, landed Company E right amid some of the heaviest fighting on the beach that day, nearly directly in front of the so-called Colleville Draw and in the face of two German 'resistance nests.'

In the distance, you can see the looming cliffs behind Omaha Beach and the smoke already obscuring the beach from grass fires ignited by allied bombers and naval artillery.

This photograph has been restored and colorized from an original black and white digital scan by the Unseen Histories Studio.

25/44

6 June 1944, c. 0800 hrs – Horsa

Stephen Wright: These guys are standing in front of a British Airspeed AS 51 assault glider, known as the ‘Horsa’. The black and white stripes on the fuselage and the lower surface of the wing are a new addition. Following the disaster during the Sicily Invasion in 1943, when Allied shipping fired on their own aircraft, the decision was made to paint identification stripes, as shown and also on the upper surface of the wings, on all aircraft participating in the Normandy Invasion.

The star replaced the RAF ‘roundel’ on American Horsas. The passenger entrance/exit has a sliding door which can just be seen. In front of the other wing, as part of the main cargo door, is another sliding door. The main spar, the part that connects the wings, comes down into the passenger/cargo compartment; the men will be saved from having to duck by boarding in two sections, rear and forward.

Their expressions say it all about what is to come. This will be their Longest Day, so far.

26/44

6 June 1944 – LCH 185

John Henry Phillips: LCH 185, which is pictured above, began life as a Landing Craft Infantry (Large). By 1944, it had seen action at the invasions of Sicily and Italy, where this photo was taken. In the build-up to D-Day, 185 was converted into a Landing Craft Headquarters, filled with radio equipment and experts trained to operate it. It was assigned to lead Force S at Sword Beach.

As a headquarters craft, 185 had both high-ranking men on board who were in charge of various aspects of the landing. There were also others like Patrick Thomas and Jack Barringer, two telegraphists who had become best friends in the months leading up to the invasion.

As the French coast came closer on 6 June, they were both amazed by the peaceful sight of two houses glistening in the morning sun. Jack noticed the stillness in the air until the naval guns opened up. He was shocked by the sight. Shells were everywhere. The bombardment shook everything in its wake.

‘Just about did a little piece,’ Jack wrote to his brother afterwards. As German machine-gun bullets rattled against the hull of 185, Patrick and Jack tried to ignore the noise to relay crucial messages across Force S, just as they had done countless times before during rehearsals in the rough seas off the Scottish Coast.

LCH 185 survived the first wave and guided in those that followed. It stayed in the water off Sword Beach for two weeks as part of the Trout Line, before an acoustic mine sent it to the bottom of the English Channel. At least 35 men on board died, and less than ten survived. Only four bodies were ever recovered.

As 185 sank, Patrick, floating in the water, could see Jack nearby. He was badly wounded and desperately searching for a lifebelt amongst the chaos. Patrick went to throw one to his best friend, but another wounded man nearby began to grab at it.

Knowing the weight of two men would pull them both down, Patrick let the second man have the lifebelt, and Jack disappeared beneath the waves. He is buried at Ranville Cemetery. Patrick visited his friend's grave for the first time 70 years later.

27/44

6 June 1944, 0840 hrs – Lord Lovat

Stephen Fisher: The 1st Special Service Brigade landed with 3rd British Infantry Division in Sword area on D-Day. The first commandos to come ashore on Queen Red were 4 Commando, with two troops of French commandos under Commandant Kieffer.

Their mission was to strike left and neutralise a gun battery in Ouistreham, a task they had completed by noon. Landing behind them came brigade commander Brigadier the Lord Lovat.

On board Landing Craft Infantry (Small) 519, Lieutenant Commander Rupert Curtis led 11 more LCI(S) towards the beach, and nosed his vessel onto the shore at approximately 08:40, just to the east of the main German strongpoint on Queen Red Beach. Stood at the bow, Lord Lovat impatiently waited for naval ratings to push the ramps down into the sea and then led his men into the surf.

Captain Evans of the Army Film and Photographic Unit captured the moment that Lovat’s personal piper, Bill Millin, got to the top of the ramp. Lovat has been identified as the man stood in the water just to the right of a line of his men (although how this identification has been made is lost to the sands of time).

Once ashore, led by 6 Commando, 1st Special Service Brigade pushed inland towards Pegasus Bridge. Crossing the Caen Canal and River Orne sometime after noon, they pressed on to reinforce the bridgehead on Breville Ridge, where they would hold the line for several months.

28/44

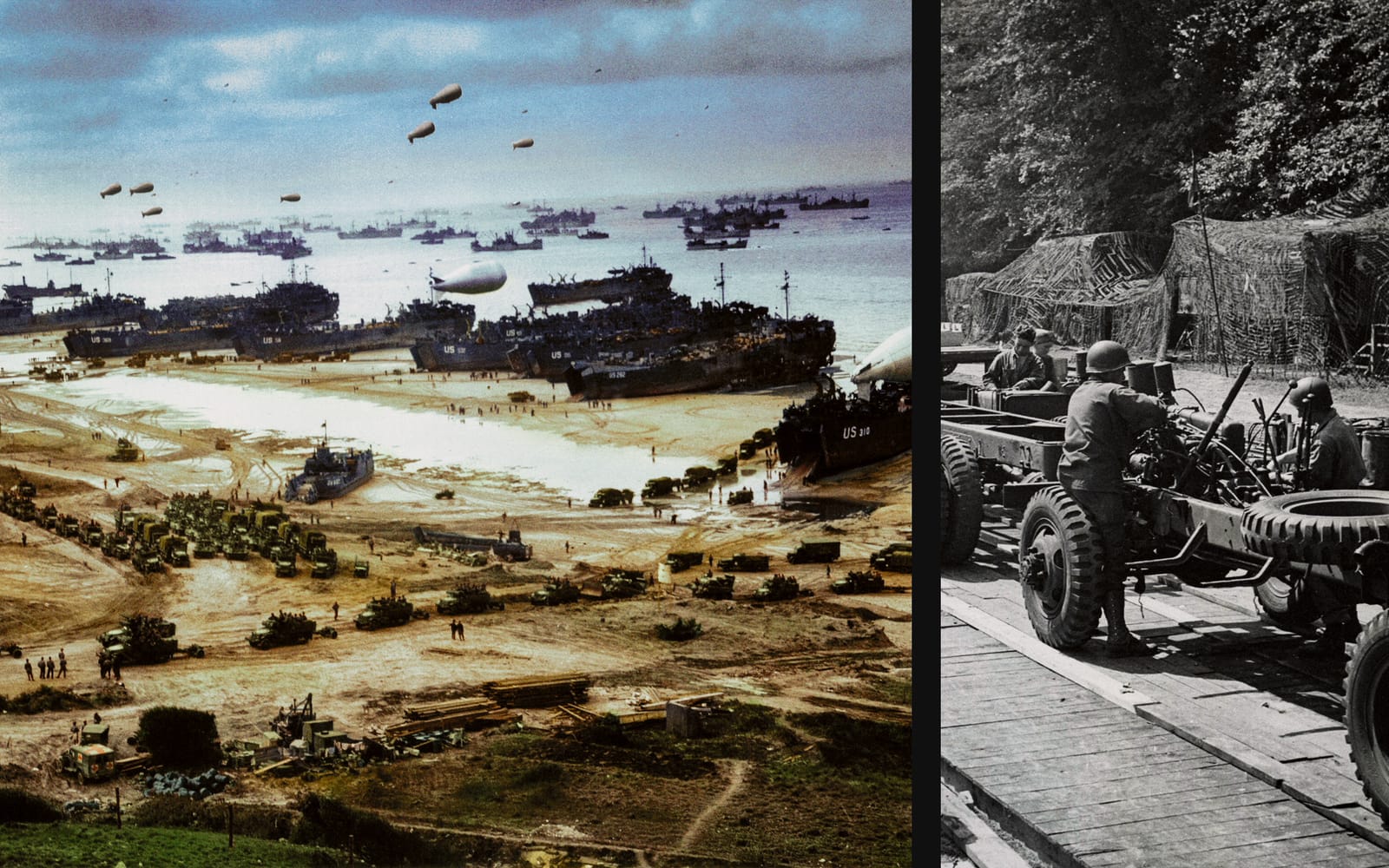

6 June 1944, 0900 hrs – Utah Beach from above

Tony Holmes: Although the medium bomber crews of the Ninth Air Force were not specifically tasked with taking photographs of the invasion beaches on 6 June, 1944, a number of stunning images like this one were taken from A-20 Havocs and B-26 Marauders.

According to the official caption that was printed on the back of this 8 x 10 photograph issued to the Press just hours after the first American troops had come ashore at Utah Beach, 'This is how the beaches of Normandy looked on D-Day from one of the Ninth Air Force Marauder medium bombers which went out in close support of Allied ground troops. Bombing from lower-than-usual altitudes, the Marauders struck behind the enemy lines at gun positions, troop and tank concentrations and vital road and rail junctions. Bomber crews came back with descriptions of ‘a Channel filled with every kind of ship ever built’ and beaches as crowded as ‘Fifth Avenue.’

This photograph was taken from one of 320 medium bombers that hit seven targets on Utah Beach from H-Hour minus 30 minutes on the morning of 6 June 1944. Beginning at 0517 hrs, single squadrons of A-20s and B-26s based at airfields in southern England commenced flying a relay system of strikes on specific targets. By the end of the ‘Longest Day’, the Havocs and Marauders had contributed more than 1000 sorties to the 4656 flown by all elements of the Ninth Air Force.

29/44

6 June 1944, 1030 hrs – Sword Beach from above

Stephen Fisher: As landing craft surged ashore on D-Day, dozens of F-4 Lightning photo reconnaissance aircraft surveyed the scene from above, capturing the landings in amazing detail.

Here the pilot is flying west along Queen White Beach in Sword Sector, overlooking the westernmost end of the landing area. From other photographs in the same sequence it is possible to tell from the fall of shadows that the time is approximately 10:30, and by studying Force S’s fleet orders and reports we can identify the vessels on the beach.

The three Landing Craft Tank, vessels with a large open tank deck to carry armour and vehicles, are part of 43 LCT Flotilla, who first landed at approximately 09:25 with vehicles of 8 Infantry Brigade (the assault brigade). But their landing was hampered by the rapidly rising tide that had already narrowed the beach to less than 50 metres.

Enemy mortar fire further complicated the landing and more than an hour later, some of the LCT are still trying to unload onto a congested beach. Next to them are two Landing Craft Infantry (Large) of 263 LCI(L) Flotilla, who carried infantry of 185 Brigade and similarly found their landing area blocked by traffic. And worse is to follow — coming in behind them are the first landing craft of 40 LCT Flotilla, carrying some 70 tanks of the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

The congestion on Sword Beach made it difficult for the units to press inland. The Staffordshire Yeomanry’s advance was delayed, but fortuitously it meant they were in exactly the right place to repel a German armoured counterattack later in the afternoon.

30/44

6 June 1944, 1100 hrs – Fox Red

Jordan Acosta: Taking shelter beneath the chalk cliffs, an American soldier is being treated by a 16th Infantry Regiment medic. This eastern stretch of Omaha Beach, code-named Fox Green and Fox Red, had some of the highest American attrition rates, owing to two German widerstandsnester ‘resistance nests’ flanking the American’s exit from the beach.

The fortified strongpoint WN62 contained a German MG 42 machine gun, which could hose down the invading force on the beach at a rate of 1,200 rounds per minute. Twenty-year old Private Heinrich Severloh, a farmer’s son from Baden-Württemburg would spend the following nine hours with a dozen men repelling the Allies from taking their objective. By the time Sgt. Richard Taylor of the US Signal Corps took this photograph, Severloh’s machine gun was the only operational weapon at the strongpoint.

In the end, American troops managed to scale the cliffs in order to capture the widerstandsnester’s adjacent to WN62 in the morning.

31/44

6 June 1944 – The Fallen

Helen Fry: D-Day was a turning point in the Second World War and an essential invasion to end the Nazi occupation in Europe. It came at great cost in human life on both sides.

This image serves as a stark reminder of the ultimate sacrifice made by the Allied soldiers who fought and fell on that historic day; a day in which over four thousand four hundred soldiers lost their lives and over five thousand others were wounded. A lone helmet balanced upon a rifle stands as a makeshift memorial amid the destroyed landscape, symbolising the loss of young life.

Nearby, ammunition boxes lie open, a testament to the fierce battle that raged across the beaches immediately after the landings. Their courage and sacrifice forged a path towards victory but the cost of D-Day was steep. The legacy of the ultimate sacrifice they gave strongly endures over 80 years later. It is a legacy that must be remembered.

This Viewfinder feature was originally published June 6, 2024 on the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings.

More

D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four – The Planning (Part 1 of 3)

In the dark days of 1940, when it seemed as likely as not that Britain would succumb to the frightful power of the Nazi war machine, the prospect of a counter invasion of continental Europe was remote. In the months and years that followed, the chances of an Allied invasion increased. A day of reckoning, it was clear to everyone, was approaching.

D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four – The Aftermath (Part 3 of 3)

For all the immense challenges, D-Day had turned out to be an unquestionable success. But at sunset that evening, the Allies were left with the sobering reflection that all they had achieved so far was the merest toehold in a small part of one coastline of northern France. Another desperate phase of the war lay ahead.

About this Feature

D-Day: Nineteen Forty-Four was an ambitious endeavour to collate and publish in time for the 80th anniversary of D-Day for June 6, 2024, and would simply not have been possible without the aid and expertise of our contributors.

We have created a list of their books on Bookshop.org, so please do give them your support. You can also support Unseen Histories by their purchasing books via the links, from which we will receive a small commission; or buy a collectible WW2 fine art print from the Unseen Histories Store, hand-printed in England and individually finished with a monogram emboss.

Thank you very much for reading •

Special thanks to the many publicists and publishers who helped us contact our contributors.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store