Demosthenes

James Romm looks back at the story of democracy’s defender

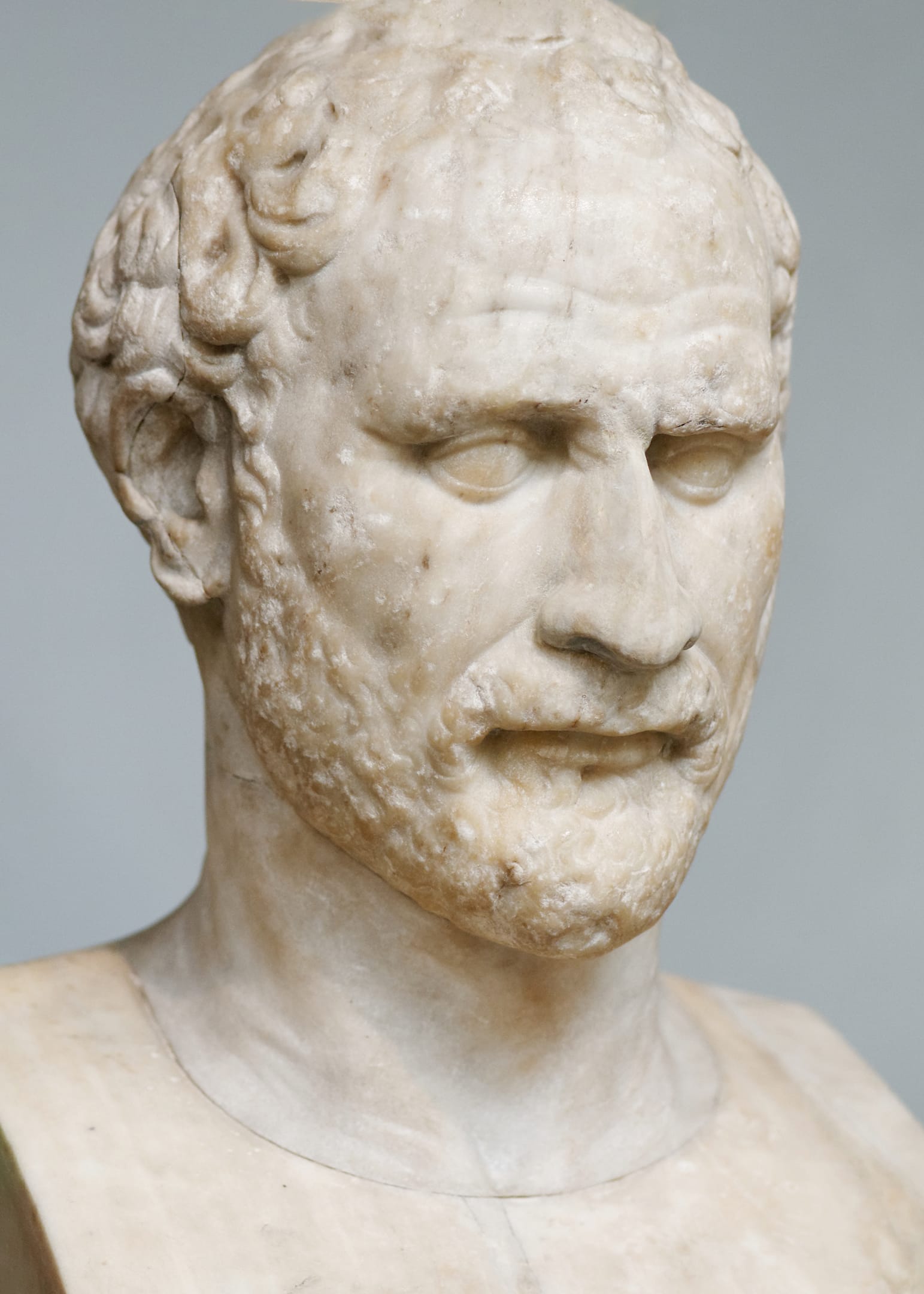

Overshadowed in our histories of Ancient Greece, Demosthenes was nonetheless one of Athens's most significant characters.

Demosthenes lived at a time of deep political division when Athens was threatened by invasion. He was no warrior but as a 'politician' he was a formidable force who made good use of his oratorical gifts.

Here James Romm, author of a new study of Demosthenes' life, casts his eyes back over a period of high political drama. This was a time in which a new word was coined: 'the Philippic'.

Most of the cherished figures from ancient history are celebrated, like Philip of Macedon and Alexander the Great, for their achievements and conquests; few are renowned for failures and defeats.

Demosthenes, the leading politician of Athens in its last days as a free nation, is one of those few. His story plays out as a minor-key counterpoint to the great fanfare surrounding Philip and Alexander – the Macedonian monarchs who dominated his era and who outplayed him at every turn.

'Politician' may seem an anachronistic term in the ancient Greek context, but that’s exactly what Demosthenes was. Unlike his great forerunners, Themistocles and Pericles, he had no military expertise or talent; his claim to leadership rested purely on his control of words.

In the radical Athenian democracy of his day – a system in which the Assembly, a vast town-hall meeting made up of all male citizens, governed by majority vote – power came from the ability to persuade. As a teenager Demosthenes set out to hone that skill to razor sharpness, overcoming a childhood stutter, famously, by practicing speeches with pebbles inside his mouth.

Other aspiring leaders were also recognizing at this time – the mid-fourth century BC – that words, more than deeds, could be a path to success, not only in the Assembly but in the many law courts of Athens, where thousands of jurors thrilled every day to hours-long speeches.

A golden age of oratory had dawned, with speechmaking replacing tragic drama, a genre by now moribund, as the city’s central source of entertainment. Demosthenes had stiff competition, especially from a man named Aeschines, his close contemporary and political rival. These two great wordsmiths came to detest one another as they wrangled before the Assembly over the great foreign policy crisis of their day – the rise of Philip of Macedon.

No one would have imagined in 359 BC, the year Philip came to the throne, that Macedon, at the time a disorganized, poorly led state, could pose a threat to great Athens. But in only a few years’ time, the twenty-something monarch revolutionized the Macedonian army and began a campaign of conquest in northern Greece.

Philip's forces were as yet far removed from Athens, beyond the chokepoint formed by the fabled Thermopylae pass, but could nevertheless do damage to Athenian allies and interests in Thrace (the northern coast of the Aegean). Athens declared war on Philip in 356 and began sending fleets to oppose him. But on each mission the ships arrived too late, or in too few numbers, to have much effect.

It took a few years of this skirmishing before Demosthenes entered the fray, politically speaking, but once he did he jumped in with both feet. In 351 he launched a series of scorching verbal attacks on Philip, the Philippics as they are known.

'When, Athenians, will you do what needs doing?' he hectored the Assembly. 'What are you waiting for?' He imagined the crowd might answer his rhetorical question, 'When some necessity arises,' then replied to that reply: 'Then what should the events before us be called? For I consider shame over one's situation to be, for free men, the greatest necessity.'

With such verbal goads he tried to get the Assembly to allot more funds, send more ships, and act more swiftly to stop the progress of Philip.

But not all Athenians thought of Philip as a threat or a foe. The city was split, with a sizeable faction, the 'Philippizers' as Demosthenes termed them, convinced that collaboration was better than confrontation.

After all, Philip was a fellow Hellene – or was he? He claimed descent from the god Heracles, and his young son, Alexander, was said to descend from Achilles by way of his mother, but Greeks were uncertain whether to credit those claims.

Demosthenes, for one, refuted them brutally in his Third Philippic, deriding Philip as a 'barbarian' – essentially, in this age, a racial slur. But another Athenian rhetorician, Isocrates, hailed Philip as an authentic Greek who could save the Greeks by uniting them in a common national cause.

Without any clear consensus on policy toward Philip, Athens signed a truce with him in 446 BC. Demosthenes and Aeschines both took part in the treaty negotiations, but in the aftermath fell out with each other over the terms of the pact.

With a keen political instinct for self-protection, Demosthenes, perceiving that his countrymen disliked the treaty, disavowed it and accused Aeschines of taking bribes from Philip to support it. The two orators conducted their first verbal duel in a trial that followed these bribery charges. The close outcome, in which Aeschines prevailed by a tiny margin of votes, showed how evenly the city was split.

To read the speeches from that trial, or from the greater showdown that followed nearly fifteen years later, gives insight into the bare-knuckle tactics of political brawling in this era. Athenian law courts had no judges or rules of evidence; swaying the jury’s emotions, using whatever lies or slanders aroused the most passion, usually won the case.

The untrammeled invective one finds in these speeches sometimes resembles the worst of today’s on-line media culture. Aeschines, for example, prevailed in part by smearing his opponent with charges of sleazy, degrading sexual behavior. Later, Demosthenes would go lower still, describing Aeschines’ mother as a cheap prostitute and his father as a lowly slave.

While leaders of Athens bickered, Philip expanded his empire. By 340 he posed such a threat that the Athenians broke apart the stone on which the truce was inscribed and went back to a state of war.

The following year Philip brought his army through the pass of Thermopylae and into central Greece, a few days’ march from the walls of Athens. A panicked Athenian citizenry convened an emergency Assembly meeting. What took place there was later described by Demosthenes.

Following custom, a crier called out the question, 'Who wishes to speak?' The call was repeated several more times, but no one came forward. Finally Demosthenes stepped to the bema, taking upon himself the burden of Athens' salvation.

'I alone, of the speakers and politicians, did not desert my place in the ranks of service, amid great perils,' he later boasted. His proposal was unanimously adopted: To forge an alliance with Thebes, Athens’ traditional rival, and meet Philip face to face in a battle to save free Greece.

That battle, on the plain of Chaeronea, was the biggest event in Greek warfare since the time of the Persian invasions, 150 years prior. Over 70,000 troops took the field, with Demosthenes fighting in armor for perhaps the first time in his life, and Alexander, now sixteen years old, leading troops on the opposite side for the first time in his life.

Numbers favored Athens and Thebes, but Philip’s superior weapons and tactics, and his newly professionalized military, carried the day. Athens and Thebes went down to defeat, and Philip’s hold over Hellas – soon to be inherited by his son – was established beyond any challenge.

Demosthenes had failed to preserve Athenian freedom, and Aeschines later blamed him, in speeches that survive, for wrecking the city’s fortunes. Perhaps though he’d only had the misfortune to come to power in an era of division and decline.

This feature was originally published December 23, 2025.

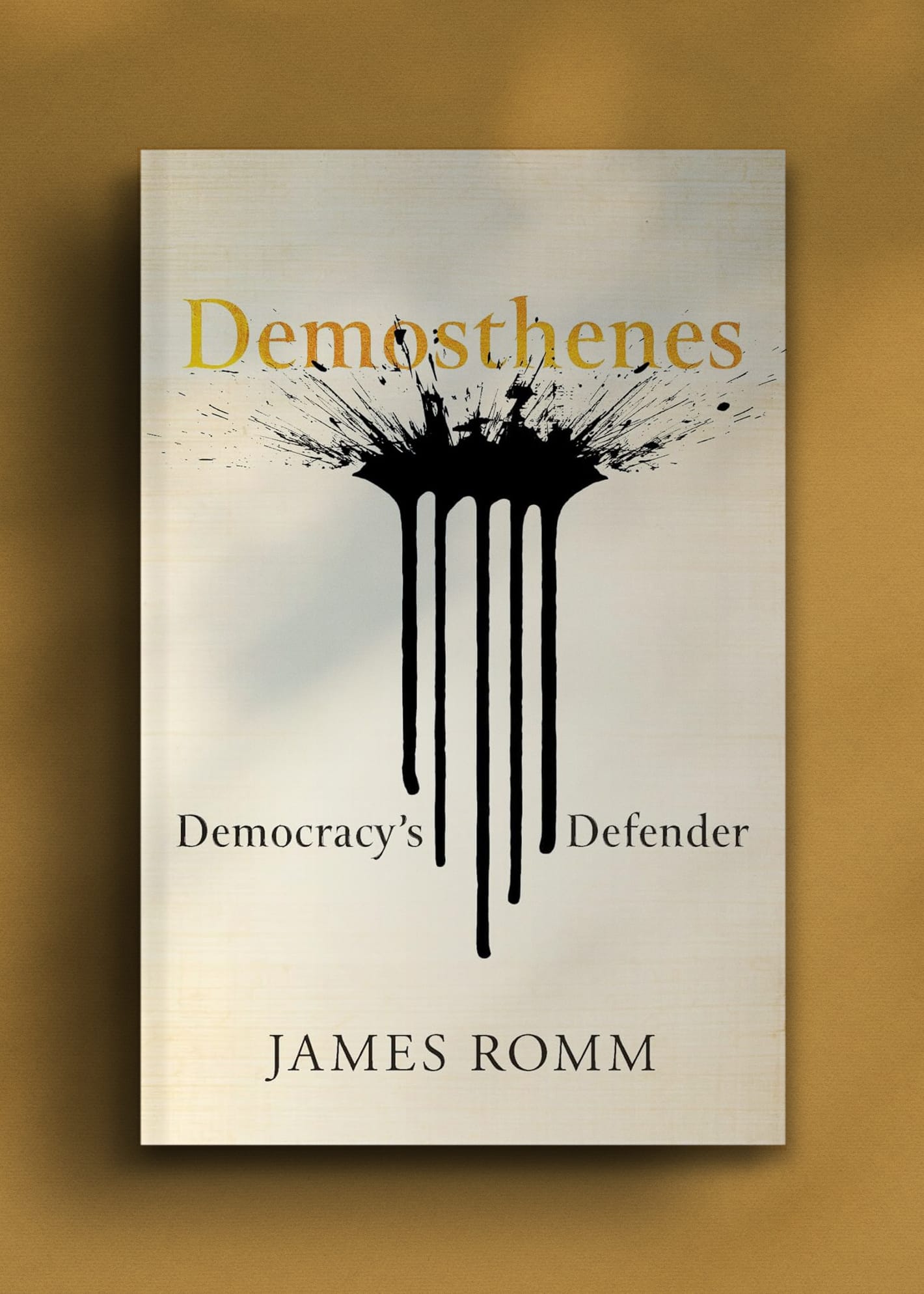

Demosthenes: Democracy's Defender

Yale University Press, 25 November 2025

RRP: £18.99 | 208 pages | ISBN: 978-0300269383

The tragic story of ancient Greece’s last democratic leader and his doomed fight to save Athens from Macedonian domination.

In the spring of 340 BCE, news arrived that Philip of Macedon had seized a town in central Greece, a base from which he could march on Athens. In the fierce debates about how to respond to the rising threat in the north, Demosthenes, the greatest orator of his day, convinced the Athenian Assembly to confront Philip on the field of battle. Though that effort failed and Athens fell into the grip of Alexander the Great, Philip’s son and successor, Demosthenes had established himself as one of history’s most eloquent defenders of democracy.

In this thrilling biography of the man who led the charge for Greek freedom, James Romm follows Demosthenes from his early career as a legal speech writer through his rise in politics, his fall from grace in a corruption scandal, and his desperate flight to the island of Calauria—where he took his own life rather than submit to Macedonian forces. As he brings to life the bare-knuckle, insult-filled verbal brawls of Athenian orators, Romm not only explores the mind of the man who took on the challenge of saving Greek freedom but also shows how democracies can be destroyed by infighting and internal division.

With thanks to Sally Oliphant.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store