1926: Driving a Flock of Sheep through London

In the 1920s the last traces of old Dickensian London faded as the modern city grew at pace

In the old days it was common to see farm animals tramping through central London. Drovers and shepherds would mingle on the streets with horses and carts, traps and barrows.

Scenes like there were a familiar feature of Dickens's novels and even in the Sherlock Holmes short stories Baker Street was animated by animals of various kinds.

But by 1926, when the photograph above was taken, this old world was in fast retreat. Motor cars and bikes, bicycles and busses, began to appear in ever increasing numbers.

It is the contrasts between these different worlds that makes this photograph so compelling.

There is the old and the new, the country and the city. At the centre of the scene the shepherd and his flock march determinedly onwards, in the cold light of a bitter winter's day.

Words by Peter Moore

Photographs Remastered and Colourised by Jordan Acosta

Kingsway, where the above photograph was taken, was still a London novelty in 1926. Broad, arrow-straight and lined with young trees, it had been built to bring a sense of order to the maze of old streets and alleyways around Holborn. To Londoners it looked a little like a Parisian boulevard, and many considered it a paragon of intelligent city-planning.

22 September 1926

For half a century or more the streets of central London have been groaning under a burden of traffic greater than they could bear.

Measures were taken from time to time to push back frontages of houses, and in one bold undertaking a channel was cut right through a jungle of slums, and the present Kingsway and Aldwych emerged.

But still, with the arrival of motors, the congestion became thicker, and in the years following the war an exasperated public clamorous that something should be done.

Just how many motor and horse-drawn vehicles were passing along Kingsway by 1926 is demonstrated by the photograph, with the wet road surface criss-crossed in all directions with the prints of wet tyres.

London's roads had never been quiet, but as car ownership became more affordable the situation became acute. A taste of what was to come was provided by the General Strike of 1926 when the trains were cancelled and people decided, like never before, to drive to work.

Friday 7 May 1926

London has never seen such traffic sights as it saw on the first morning of the strike. All approaches to the centre of the Metropolis, North, South, East and West, were congested with seemingly endless lines, as many as three and four abreast, of motor vehicles.

The ingenious motorist who knew his London could sometimes find means of circumventing the main stream, but even he would find himself caught in the same stream, perhaps a quarter of a mile further along.

The energetic push cyclists threaded their way in and out defiantly. They had the best of the bargain with their supply mobility. Motor-cars suffered from wear and tear, but considering the congestion, there were astonishingly few mishaps of any description.

London on its own wheels took its misfortune of this first day of self-help as a joking adventure. Perhaps a generation hence, when one man in every seven, as in America, has his car, the streets of London will look as they looked on Tuesday morning. But by that time the joke will have become a traffic scandal.

Efforts were underway to tackle this emerging problem. Kingsway, indeed, was an innovative space in several different ways. At its southernmost-end, where it joined the Strand a 'traffic experiment' was underway with the introduction of a new circular route called, intriguingly, 'a roundabout'.

Another initiative was to clear a great patch of wasteland belonging to London County Council at Aldwych into an exciting new civic space, a 'car park'. Here, wrote the motoring correspondent for the London Daily Chronicle, vehicles could be parked all day in long neat lines, not bundled into single slots on the side of the roads.

At a century's distance it is entertaining to look back on these early appearances of things that would become a common feature of our modern, motorised world. But in 1926, while this culture was very much in a state of emergence, drivers were left to contend with old perils.

Animals were one of these. Driving sheep into the city might have been an age-old custom, but it was becoming a troublesome one too. As far back as 1909 sheep driving was banned on Sunday in the borough of Islington. It persevered elsewhere, however, and the public records of the time recount collisions between animals and the cars.

‘You are a disgrace to the motoring public to drive at such a reckless speed through a flock of sheep’, one driver was told by a judge that year.

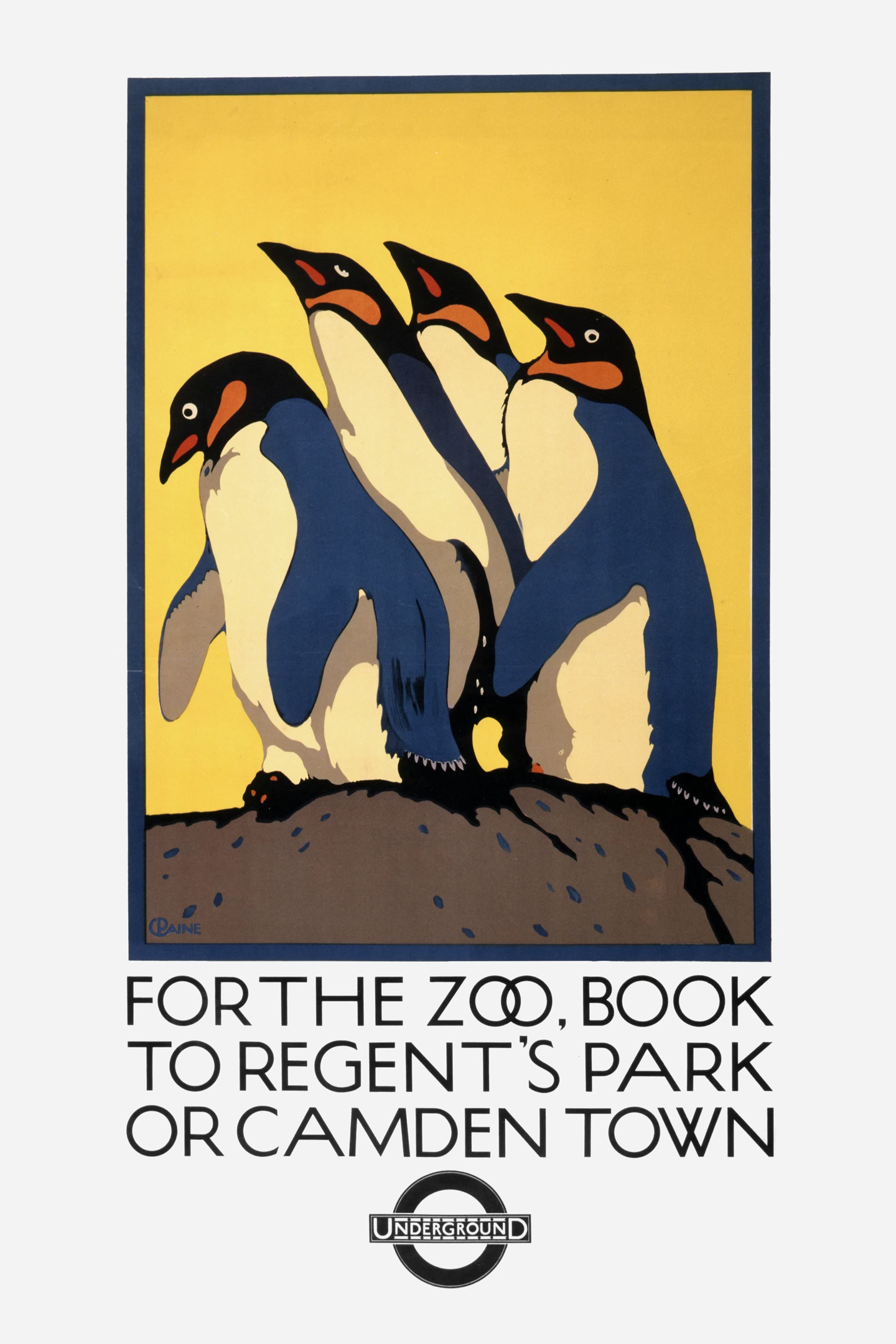

While the shepherd standing to the left of his flock in this colourised photograph has his animals very much under control, the same could not be said for a mountain sheep from Sardinia—a 'moufflon'—that generated a lively story when it escaped from London Zoo.

23 February 1926

It was being boxed for removal when it got loose. Seven keepers took part in the hunt. They began with a brisk run around the grounds and drove the fugitive into a paddock bordering the park. But the animal cleared the six-foot railings and set off at a great pace down the Broad Walk.

As the keepers were unable to scale the railings and had to make a detour, the sheep was lost sight of, but so much excitement had been caused by the strange runaway that there was no difficulty in picking up information as to its whereabouts and it was found to have reached the Outer Circle.

But for the fact that the road was up, the Moufflon would have dashed into the Euston Road; but finding its way barred, it doubled on its tracks and took refuge in the grounds of Bedford College.

Just as it was on the point of being capture the animal, without taking a run, leapt the high fence, and once more careered across country, bounding across every obstacle in its path.

Several dogs joyously joined the chase but were called off by their owners and the Mouffion sped on uninterrupted.

It made a false move, however, on taking to the Inner Circle, for it ran into a crowd of navvies, who, in response to the hue and cry, surrounded the spent animal and eventually secured it.

After the keepers had regained their breath and composure, the fugitive was carried back, bodily, to its quarters.

By the time London Zoo's mountain sheep escaped, animals were becoming a much rarer sight on the capital's streets. Motor cars were bringing a new kind of excitement, although nostalgists may lament the old days when one might glance up and see a zebra trotting along the road at Elephant and Castle.

Many today, however, still remember that one quirk of being awarded the Freedom of the City is the privilege of driving one's flock across London Bridge. When she was presented with this honour in 1987 Princess Diana was delighted. ‘I promise I will give good warning’, she told a packed audience at the Guildhall, ‘before I avail myself of this privilege’ •

This Snapshot was originally published January 31, 2025.

Ad: Unseen Histories relies on your patronage to operate. Our webstore offers a wide range of collectible museum-grade fine art prints, hand-printed in England for your wall space.

ColorGraph™ presents the most incredible colorized photography bringing the past to life. From start to finish, a ColorGraph print is made with exceptional care and attention. To mark its provenance, we emboss each one in the final stage of the hand-finishing process.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store