Early Modern Regime Change

Susan Doran examines the fault line between two of England's great dynasties: the Tudors and the Stuarts

On the death of Queen Elizabeth I in March 1603 one of the longest and dramatic reigns in English history came to an end.

As Elizabeth had no heir of her own the crown passed to King James VI of Scotland, Elizabeth's closest royal relation. The Age of the Tudors had ended. The Age of the Stuarts had begun.

James soon started out for the Great North Road on his journey to London. This was a route that thousands of others had made before. But James's was to be a journey of unique historical significance.

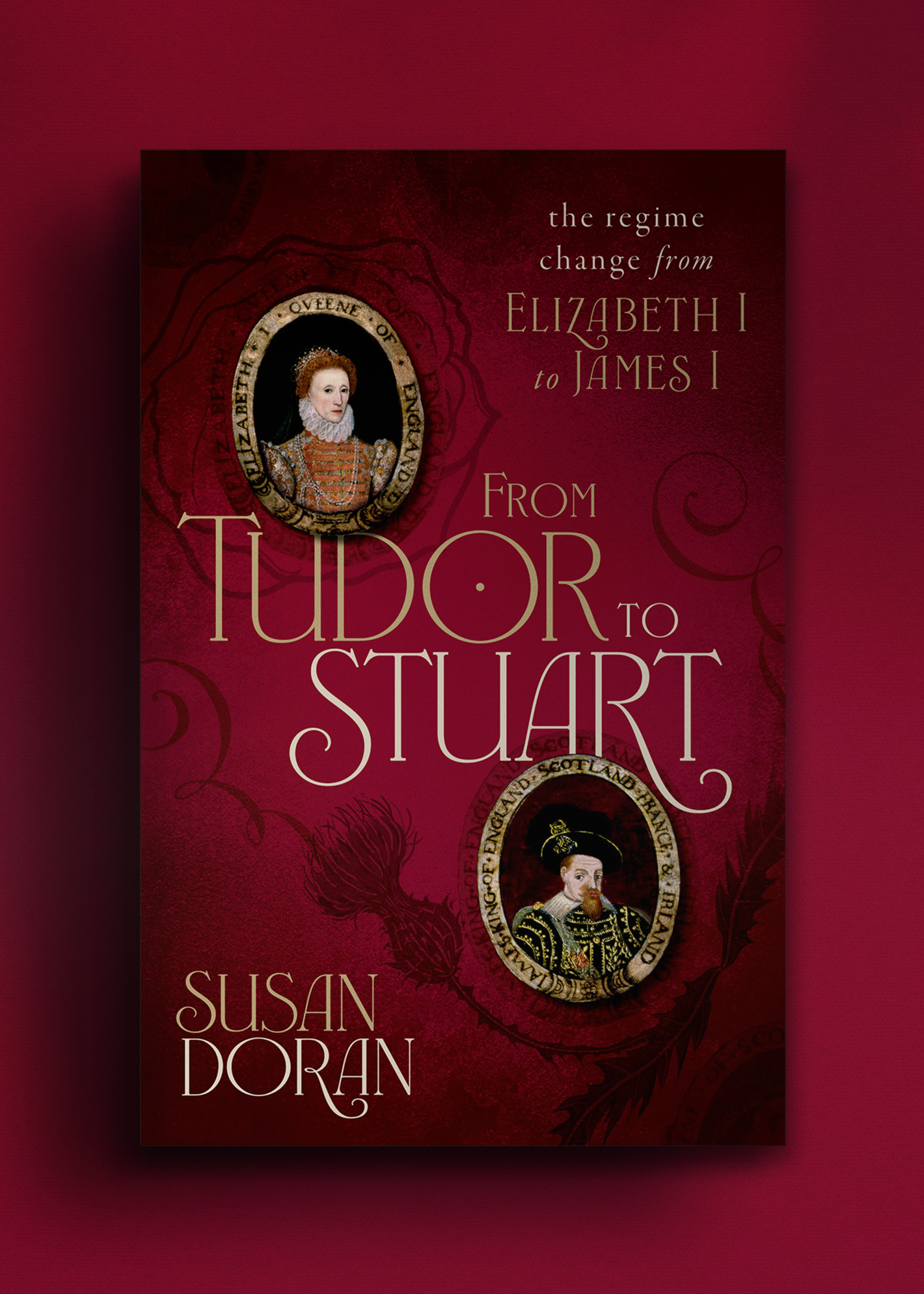

In her new book, From Tudor to Stuart, the historian Susan Doran has examined this anxious, exciting, transitional period of history.

Here she explains what drew her to this time and what she learned while studying it.

In writing this new book, I went on my own journey from the Tudors to the Stuarts.

Although I had scraped the surface of King James I’s reign when teaching an outline paper on early modern British history at Oxford, I had never delved into the primary sources of the Jacobean period until I embarked on this project in 2016.

All my research and interest had previously been concentrated on the Tudors, and especially Queen Elizabeth I. So, why did I decide to move into this unfamiliar territory?

In part it was because I felt the need for a fresh challenge; was there anything new for me to say about the Virgin Queen?. Also, I had long been studying the Elizabethan succession question and was now keen to find out what happened next. Did James settle quickly into Elizabeth’s shoes? Did the arrival of a foreign king with a family following the death of an unmarried home-grown queen bring about major changes to England’s government and politics?

These were the questions I set myself when determining to study the first decade of James I’s reign.

I soon discovered that the transition to James’s reign was less smooth than usually stated. Although he had the best title by primogeniture, his claim to the throne was problematic because English common law prohibited aliens from owning property, while Henry VIII’s will of 1546 had effectively excluded the Stuart line.

Moreover, Elizabeth had not nominated James as her heir in parliament, and not everyone believed the tales of her recognition of him on her deathbed. For some, therefore, James was not a hereditary monarch but one who had been elected by the political elite in a dubious constitutional procedure.

Even worse, voices were soon heard in England against a Scot taking the throne. Not only was Scotland a long-term enemy of the realm, but also negative stereotypes about the ‘beggarly Scots’ raised fears that they would follow their king to London and benefit from royal patronage at the expense of native-born Englishmen.

James’s early appointments fuelled these anxieties and played a role in two of the early plots against him.

Historians previously had not fully assessed the impact of the new dynasty on English history. To do so, I had to cross the invisible boundary of 1603 that ended or started so many existing history books.

It was immediately apparent that the two monarchs were very different characters. Elizabeth, for example, was frugal, James profligate; Elizabeth’s speeches were terse, James’s orations longwinded; Elizabeth avoided talking about difficult subjects – whether religious or constitutional – whereas James enjoyed tackling them head-on; and James tended to be more confrontational than Elizabeth, less inclined to mount a charm offensive when encountering political opposition. All these personal differences had political repercussions.

Other differences in the two monarchs’ style of government quickly became obvious. I found, for example, that whereas Elizabeth had tended to interact regularly and informally with her principal secretary and councillors, James usually corresponded with them by pen, since he spent weeks away from London on hunting expeditions with a small coterie of huntsmen who were mainly Scots.

Similarly, while I had already known that the presence of a royal family put a severe strain on royal finances, I now came to appreciate Queen Anna’s important contribution to court culture and role in filling the ceremonial void when James was absent.

Just as important, 1603 appeared to be a cut-off point in English history, not just because of regime change itself, but because of the new issues and problems which then came to the fore.

No longer was the succession question, which had dogged all the Tudors, important since the new king had an heir and spare, or at least he did until 1612 when his first-born, Prince Henry, unexpectedly died.

The main political concerns of James’s early years were England’s constitutional relationship with Scotland and the unpopularity of high-profile Scots within James’s inner circle at court. Admittedly, the issue of union with Scotland died away after 1610 when it was effectively rejected in the House of Commons, but the acrimonious parliamentary debates had served to poison James’s relations with his parliaments.

Several decades later, Charles I’s attempt to bring Scotland’s Church more in line with that of England had disastrous consequences for both countries and was one of the catalysts for the mid-century Civil War.

Yet, I soon learned that much else remained remarkably unchanged after James’s accession. The new king took as much care with his royal image as had his predecessor. The court calendar under him differed little from that in the recent past: both Elizabeth and James enjoyed Christmas revels, celebrated St George’s Day, went on summer progresses, and marked royal anniversaries with prayers and tournaments.

For the most part, central government institutions (the privy council, parliament, the judiciary) and local (JPs, recorders, and sheriffs) remained untouched.

Nor were there dramatic changes in personnel until the death of Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, in 1612, even though a few political figures – such as Sir Walter Ralegh and Henry Lord Cobham - left the political scene and some outsiders, like Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton took power. James’s sexuality remained under wraps until later in the reign.

When it came to religion, I discovered to my surprise that there was little change after 1603, despite James’s Calvinist education, ostensible readiness to listen to calls for reform, Catholic wife, and reputation for ecumenism. Both monarchs were committed Protestants who demanded that their subjects attended church services which followed the authorised prayer book and had no truck with those who would not conform to its rituals.

Both monarchs abhorred Presbyterianism and hated Jesuits not least because of their perceived challenge to royal authority. In their foreign policy, there were also striking similarities even though James immediately ended the war against Spain and cracked down on privateering, which he deemed piracy. The two monarchs shared a common approach to the two main Catholic powers, preferring peace to war, not least because England could not match the financial and military resources of France or Spain.

The mood in England on Elizabeth’s death was a desire for both continuity and reform, continuity to avoid the shock of regime change and reform because the wars against Spain and in Ireland had exposed many weaknesses in the Elizabethan state.

In the formal eulogies on her death and as the subject of several plays shortly afterwards, the queen was praised for her unusual learning, facility with languages, personal piety, love of peace, and promotion of Protestantism at home and abroad, while her reign was depicted as a time of peace and prosperity.

However, petitions, sermons and poems in 1603 presented an alternative narrative, since they listed ills that had been allowed to fester during her reign such as a sycophantic court, corrupt practices, legal oppressions, and a heavy tax burden. Consequently, many people hoped for better times under the new king.

However, continuity ultimately ruled the day as James’s government failed to deliver the much-needed reforms to remove abuses and inefficiencies in the running of the state.

I thoroughly enjoyed working on this book. Interesting characters emerged from the documents, and there were exciting stories to tell: plots galore, treason trials, births and deaths of royal children, the making of peace with Spain, and much else.

The Gunpowder Plot is a case in point; we all know that there was a plot to blow up the houses of parliament on 5 November, but I for one was unaware that the conspirators attempted to raise a revolt in the Midlands nor that they had made a heroic last stand at Holbeach House.

Too long neglected, the early Jacobean period is as important as it is fascinating. It saw the establishment of England’s first colony in America and the plantations of Ulster, both of which are crucial events in British history.

Culturally, it was significant too. More plays were performed at court under James than under Elizabeth, while London playhouses produced major works by Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and other leading dramatists.

Queen Anna is best known as the sponsor of court masques, but she and Prince Henry took the lead in promoting Italianate music, architecture, and painting styles at court which afterwards became fashionable in England. All these stories and developments have their place in my book •

This feature was originally published July 22, 2024.

From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I

Oxford University Press, 6 June, 2024

RRP: £30 | 656 pages | ISBN: 978-0198754640

“Immaculately researched” – Daily Telegraph

From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I tells the story of the troubled accession of England's first Scottish king and the transition from the age of the Tudors to the age of the Stuarts at the dawn of the seventeenth century.

From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I tells the story of the dramatic accession and first decade of the reign of James I and the transition from the Elizabethan to the Jacobean era, using a huge range of sources, from state papers and letters to drama, masques, poetry, and a host of material objects.

The Virgin Queen was a hard act to follow for a Scottish newcomer who faced a host of problems in his first years as king: not only the ghost of his predecessor and her legacy but also unrest in Ireland, serious questions about his legitimacy on the English throne, and even plots to remove him (most famously the Gunpowder Plot of 1605). Contrary to traditional assumptions, James's accession was by no means a smooth one.

The really important question about James's reign, of course, is the extent of change that occurred in national political life and royal policies. Sue Doran also examines how far the establishment of a new Stuart dynasty resulted in fresh personnel at the centre of power, and the alterations in monarchical institutions and shifts in political culture and governmental policies that occurred. Here the book offers a fresh look at James and his wife Anna, suggesting a new interpretation of their characters and qualities.

But the Jacobean era was not just about James and his wife, and Regime Change includes a host of historical figures, many of whom will be familiar to readers: whether Walter Raleigh, Robert Cecil, or the Scots who filled James's inner court. The inside story of the Jacobean court also brings to life the wider politics and national events of the early seventeenth century, including the Gunpowder Plot, the establishment of Jamestown in Virginia, the Plantations in Ulster, the growing royal struggle with parliament, and the doomed attempt to bring about union with Scotland.

“An encyclopaedic synthesis of recent research, From Tudor to Stuart will be indispensable for students of the period”

― John Guy, Literary Review

“One of the delightful aspects of this book is the author's flair for cultural history and literary readings alongside her mastery of the politics and economics of the period... From Tudor to Stuart will surely land on every student reading list, not only because of Doran's pedigree, but because it manages to give us a new perspective on an overstudied period”

― Kate Maltby, Financial Times

With thanks to Anna Gell.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store