Thebes' West Bank

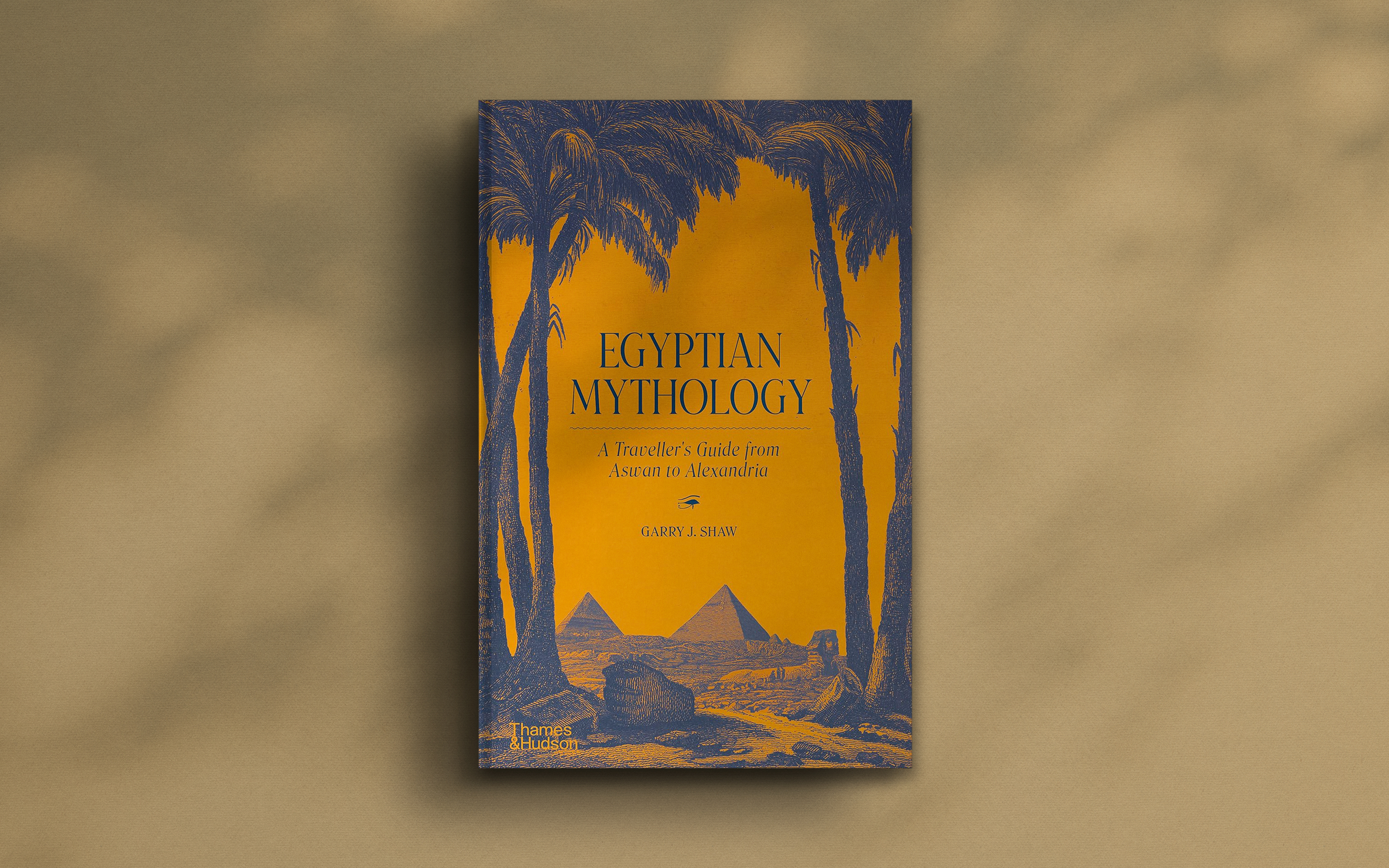

Garry J. Shaw introduces us to the elaborate temples of the Ancient Egyptians, and their close association with myth and legend

Join Egyptologist Garry J. Shaw on a tour up the Nile, through a beautiful and fascinating landscape populated with a rich mythology: the stories of Horus, Isis, Osiris, and their enemies and allies, tales of vengeance, tragedy and fantastic metamorphoses. Shaw not only retells these stories with his characteristic wit, but also reconnects them to the temples and monuments that still stand today, offering a fresh look at the most visited sites in Egypt.

With an introduction by Garry J. Shaw

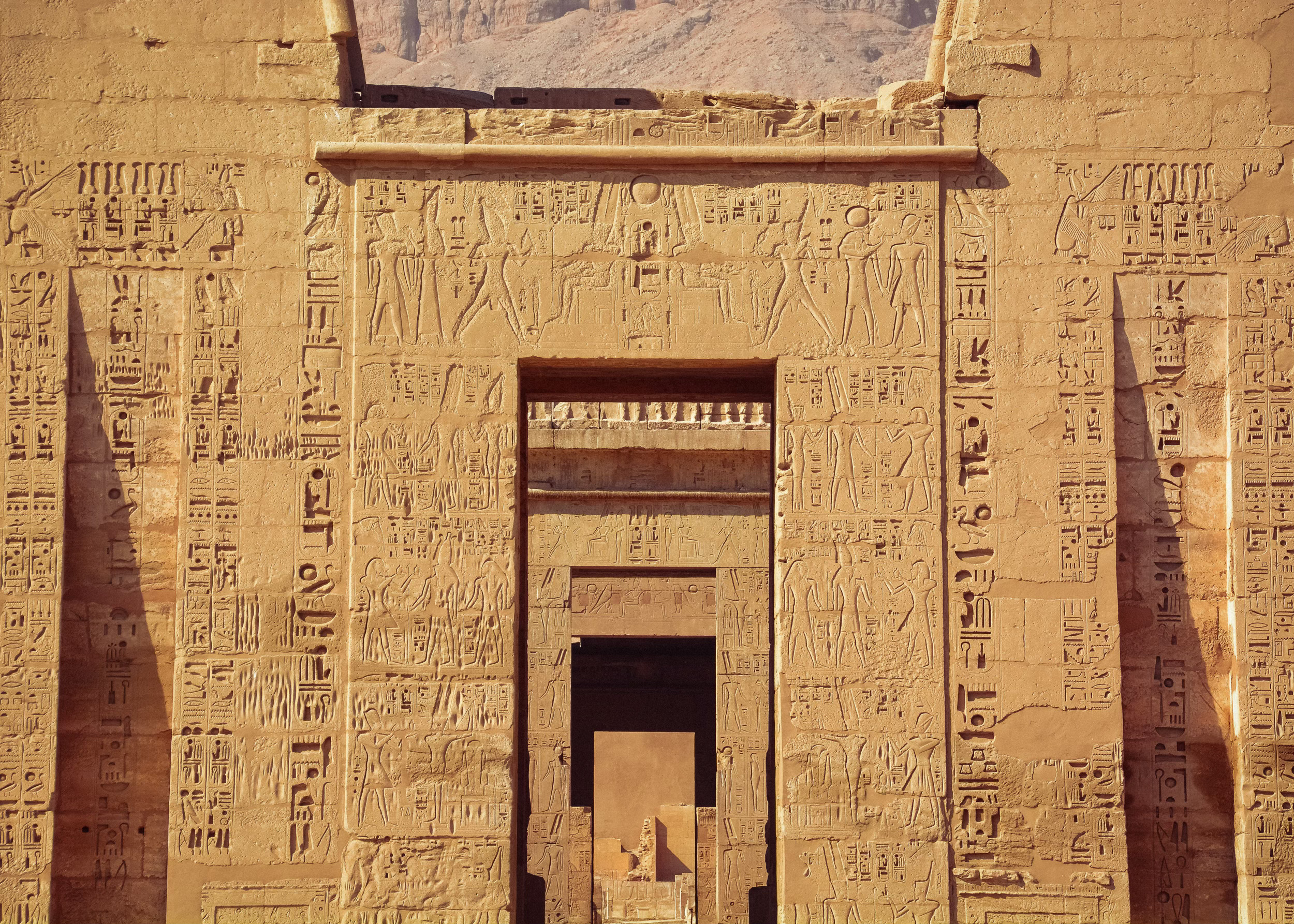

Egypt’s ancient temples and tombs, with their carefully-executed paintings of deities, pharaohs and mysterious hieroglyphs, never fail to amaze visitors. There’s nothing like exploring the vast ruins of the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak; or staring upwards towards the peak of the Great Pyramid at Giza; or watching the water of the Nile splash against the rocks near the Temple of Isis on Philae Island.

But what were the myths and legends of these sacred places? Why build these elaborate temples and tombs? What meaning did they have to the ancient Egyptians?

In my book, Egyptian Mythology: A Traveller’s Guide from Aswan to Alexandria, we go on a journey along the Nile. Travelling from south to north, following the river’s flow, we visit Egypt’s ancient sites – tombs, temples, the remains of settlements and cities – some well-known, others more obscure, to learn about the myths and legends of the country’s ancient deities, and the rituals and festivals dedicated to them.

Along the way, we meet gods and goddesses, such as Osiris, Isis, Horus and Hathor, and demons and ghosts – beings that could be helpful or dangerous, depending on their mood. The stories that survive to us, preserved on temple and tomb walls, on papyrus rolls and broken pots, describe the gods as beings of immense power, who had jobs to perform in the cosmos, families and emotions. We see how the Egyptians interacted with them, praised them, and in return, how the gods favoured Egypt.

Together, these myths, legends and stories provide an insight into the ancient Egyptian mind. Our journey across Egypt is a journey into their world.

— Garry J. Shaw

For references please consult the finished book.

Celebrating with the Dead

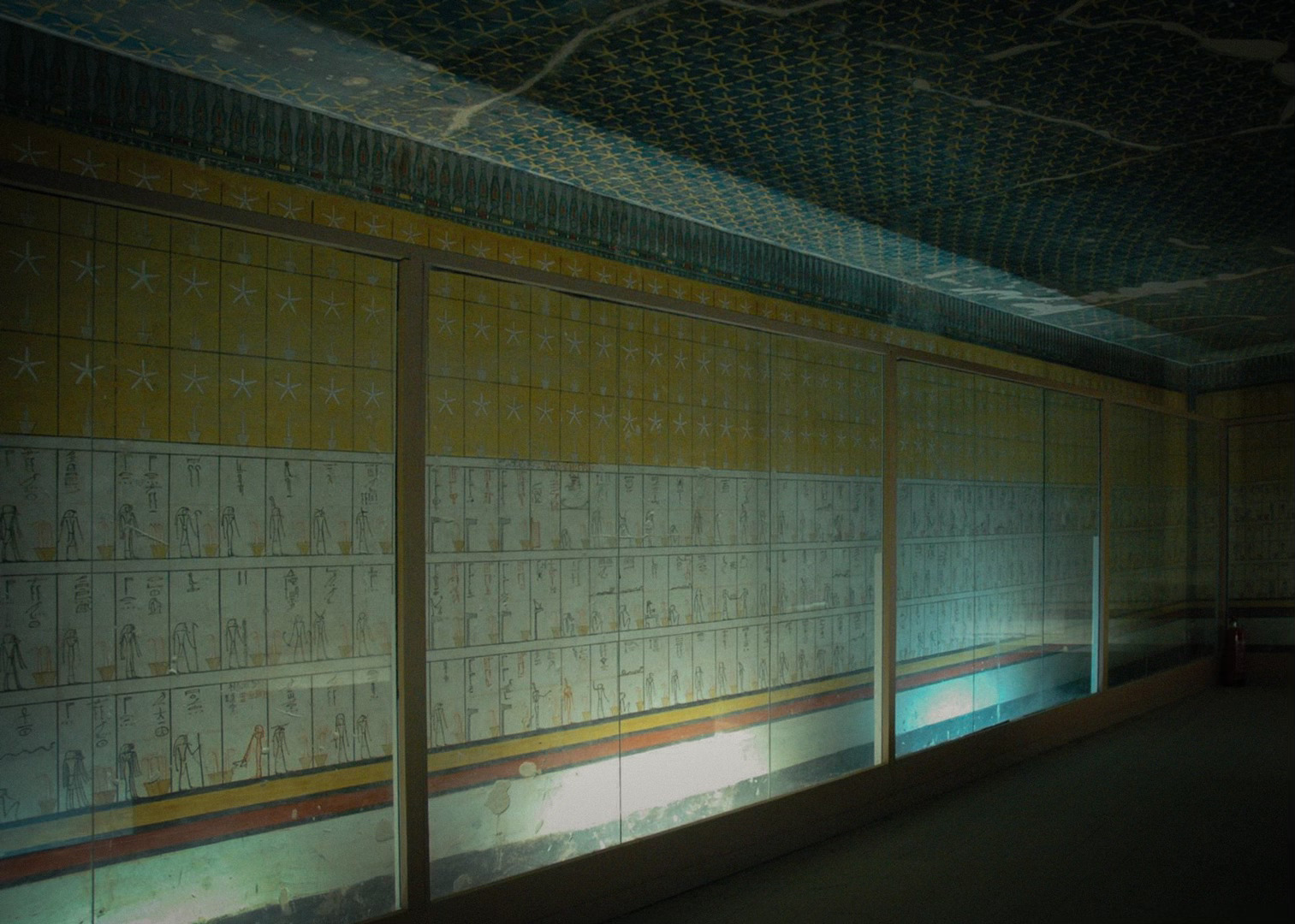

When you stand in a tomb, there's a sense of disconnection from the world. Perhaps it's simply knowing where you are and where you'll one day be, but something makes you feel like you're standing in a place removed from reality. This is certainly the case in the Valley of the Kings; and for me, particularly in the burial chamber of King Tuthmosis III (r. c. 1479-1424 BC). Take a set of modern, metal steps through a rocky crevice, then proceed down through ancient, carved corridors, and you'll reach the king's final resting place. It isn't the most lavish or the grandest tomb in the Valley, but it certainly feels the most adventurous. At first glance, the burial chamber's moodily up-lit decoration appears almost simplistic – inked hieroglyphs, stick figures, winged snakes, boats and mysterious mounds, within borders of pink and yellow, sit below a starry sky. But the paintings and writings that wrap around the room like an unfurled papyrus scroll are anything but simple.

They are a complex guide to the king's afterlife in the netherworld realm of the Duat, including a detailed catalogue of gods and demons and an explanation for the sun god's disappearance at night. Most importantly, they represent the eternal struggle between order and chaos, in which the king, united in death with the sun god Re, fights to keep the cosmos active. The drama of these scenes is at odds with the quiet of the tomb. I hear the gentle hum of an air pump. The chatter of visitors, echoing from other corridors. The shuffle of the tomb guardian's sandals. For a moment, I am elsewhere.

The Valley of the Nobles: staying alive (in death)

'I oversaw the digging of his majesty's cliff tomb, alone, none seeing, none hearing.'

– In his tomb, the courtier Ineni refers to his work in the Valley of the Kings, c. 1465 BC

Now that we've set the scene, it's time to get spooky. The Egyptians used Luxor's West Bank as a cemetery for thousands of years, starting perhaps as early as c. 2520 BC. The hills of the desert escarpment are dotted with rock-cut tombs – the burials of local families of importance: viziers, high priests, military men, scribes and everyone in between. But the Egyptians' relationship with the dead didn't end with the sealing of a coffin. A typical Egyptian tomb had two main sections: the burial itself, hidden from view underground, where the tomb owner's mummy, along with the mummies of his family, lay in their coffins, sealed away with their grave goods; and a public 'chapel' that any passer-by could enter. This was a space filled with painted scenes and inscriptions highlighting the deceased's good service for the king and gods.

What was the point of all this? The Egyptians believed that an individual was composed of various aspects that separated at the moment of death to explore their own destinies: there was the ka, a form of life-force or double that remained in the tomb; the ba, representing movement and personality, which entered the Duat but could return to the mummy at night to sleep and recharge; the shadow, which was a double of the person, present throughout life, but free in death (just like Dracula's shadow); the body, which needed to be preserved as a vessel for the ba; and the name, which identified the person. The loss of any one of these aspects caused the second (true) death: obliteration from existence. Destroy all copies of a person's name, and they vanished for ever. Burn the mummy and it was the same fate, unless that person had invested in ritually awakened statues, inscribed with their name. Sometimes, the Egyptians sealed these backup statues in special chambers within the tomb chapel to protect them from damage. Visitors could only see these statues through small holes or slits in the walls, installed so that the scent of burnt offerings or incense could waft in and be experienced by the spirit inhabiting the statue.

The ka and the ba required sustenance in the afterlife. The painted scenes and texts inscribed on the walls of the tomb chapel magically provided this sustenance, with the ka able to enter the scenes, like a form of ancient virtual reality. But the nourishment provided wasn't as potent as true, physical offerings made by a visitor. This is why the Egyptians dedicated so much space in the tomb chapel to advertising a person's worthiness: it was all an effort to tempt you to make offerings and say prayers to this obviously deserving individual. You were meant to be impressed. The inscriptions included plenty of copies of the deceased person's name, too, so that there were backups, just in case some nefarious visitor decided to scratch the name away. As you can see, the Egyptians developed many practical plans to ensure their afterlife existence. Every problem had a solution.

The Beautiful Festival of the Valley

Every year at Thebes, during the ninth month, the Egyptians celebrated a major two-day event called the Beautiful Festival of the Valley. The gods of the Karnak temple precinct – Amun, Mut and Khonsu – left their shrines and crossed the Nile to the West Bank, accompanied by the pharaoh. Together, they travelled to each of the royal mortuary temples, one by one, to visit the kings of the past, who in death had fused with local manifestations of Amun. Meanwhile, the people of Thebes celebrated in the necropolis, visiting their own lost loved ones and ancestors. At the tombs, families made burnt offerings for the dead, while the temples provided free food and alcohol for the celebration. Even the dead got drunk. This temple-sponsored intoxication wasn't just to ensure that a good time was had by all: the drunken haze was thought to blur the lines between the realms of the living and the dead, and to create a calm mood, just as alcohol had calmed the bloodthirsty Hathor-Sekhmet in myth. Inebriated families spent the night among the tombs, wearing flower garlands called wah-collars, which served as symbols of regeneration. They offered these garlands to the dead too.

Interactions with ghosts were not unusual in ancient Egypt. The dead played an important role in daily life. They were part of existence, just the same as anything else in the cosmos, from cats and priests to celestial cows. Unlike modern movies and literature, ancient Egyptian stories don't present encountering a ghost as a terrifying experience: most of the time, it's just like meeting an old friend. And the dead had access to the gods, so if you wanted a powerful divinity to improve your life, a conversation with a ghost who might be persuaded to pass on a message was a good starting point. At the same time, the dead had expectations of the living: they wanted a steady supply of offerings and a well-maintained tomb. And they could cause serious problems if their expectations weren't met - such as ruining your life. If you didn't know a friendly ghost, it was possible to summon one, as long as you knew the right spells. To summon a dead man (a zombie?), you placed the dung of an ass and an amulet of the goddess Nephthys on a brazier, forcing him to enter your chamber. To summon a spirit, you placed two specific types of stone (sadly difficult to identify) onto the brazier, and once the spirit had entered, it was a good idea to burn a hyena's or hare's heart on the brazier, too. Another type of stone, unidentified but said to be connected with the sea, summoned a drowned person.

Given that the Egyptians believed the person to scatter into various independent spiritual aspects at death, it's interesting that only the shadow, ba and akh – a status given to spirits who had passed Osiris' judgment – appear as ghosts in stories and spells, with the akh being the most commonly attested. There are no ka-ghosts or stumbling mummies. Artistic representations of spirits are rare. On a wall in the tomb of the workman Irinefer, at Deir el-Medina, the shadow is a standing man, thin and entirely black, as if in silhouette. Paintings of the dead as an akh are virtually non-existent, though texts describe them as manifesting in human form. Images of ba-spirits are more common, and usually show them as human-headed birds.

The Book of the Dead: a guide to the afterlife

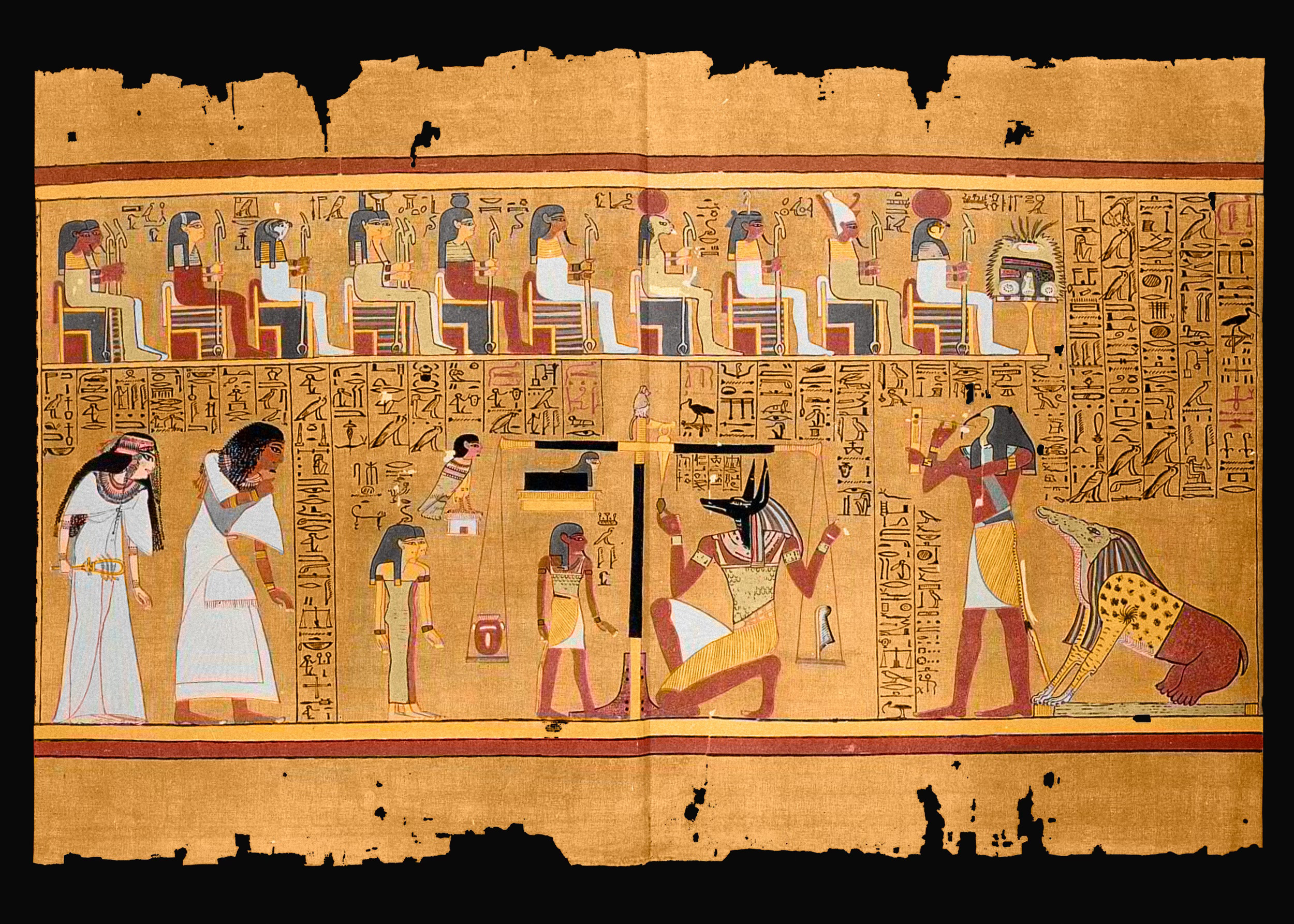

During the New Kingdom, a deceased Egyptian nobleman wouldn't be caught dead in his tomb without a Book of the Dead. This composition, known as '(The Book of) Going Forth by Day' to the ancient Egyptians, provided the deceased with a guide to the otherworld realm of the Duat – the place through which the sun god travelled at night, and which in death spirits traversed to reach Osiris' judgment hall. The Book first makes its appearance shortly before the New Kingdom, and many of the spells can be traced back to the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom, themselves developed from the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts. Spells from the Book of the Dead were written on papyrus, leather, linen, amulets, figurines and on the walls of tombs and coffins – items and locations that would be close to the deceased's mummy in the burial chamber. But there are indications that the Egyptians read the Book in life too, giving ample time for them to prepare themselves for the many oddities and trials that they would encounter in the Duat.

For the Duat was a terrifying place. It was filled with dangerous beings, whose sole purpose was to frustrate the deceased's progress, from men, gods and spirits of the dead to strange demons – creatures that walked upside down, drank blood and ate their own excrement and entrails. To make it through safely, the deceased had to call on the Book's magic - pronouncing its spells and performing rituals over specific objects – or rely on good old-fashioned weapons. But the afterlife wasn't all bad. In death, each person became an Osiris – they even used his name as a title – and so partook in the god's powers and regeneration. Some deities provided food and aid, while the deceased, through magic, could transform into certain gods - including Atum-Khepri, Shu and even Re – and use their powers and influence to aid their journey. The spirit could also change into various creatures: a crocodile, a snake, a falcon, a phoenix and a swallow among them. Because of the advantages such magic gave the dead, demons often tried to steal their magic and had to be repelled with spells.

The Book of the Dead provides details on specific otherworld destinations, including caverns, mounds, gateways, waterways, fields and mountains. The geographic links between these places aren't always clear – you can't use the Book of the Dead as a map of this mysterious world. Of the many locations described, the gateways were of particular importance, because the dead had to pass through them to reach the judgment hall of Osiris. Spell 144 says that there were seven gateways, each protected by a keeper, guard and announcer. The deceased had to announce the name of each demon in order to pass safely. Spell 146, however, says that there were twenty-one gateways, each with a guardian and doorkeeper. (Though these spells contradict each other, it was best to include both – one had to be correct!) Such demons might sound fearsome, but in the Duat, if a spirit pronounced a being's (or even a thing's) name correctly, it ceased to be dangerous, and became their supporter.

The deceased's goal was to pass Osiris' judgment, and so gain the rank of akh; this identified the person as a transfigured spirit in human form, an eternal being of light, with free movement within creation. In this form, many afterlife destinations were available, depending on the spirit's mood. The dead could join Re on his solar boat and help him in his endless battle against chaos; take part in the tribunal judging between Horus and Seth; freely enter and leave the realm of the dead; transform into any shape; play the board game senet; and eat Osiris' food offerings. One afterlife destination prominently featured in the Book of the Dead's artwork, and sometimes on tomb walls, is the Field of Reeds. This was a heightened version of Egypt, literally – spirits were taller than in life, and the crops grew higher too. There, the dead ploughed their bountiful fields, sailed on their waterways, and worshipped their ancestors and gods, safe in the knowledge that the Field's walls of iron barred entry to any dangerous forces.

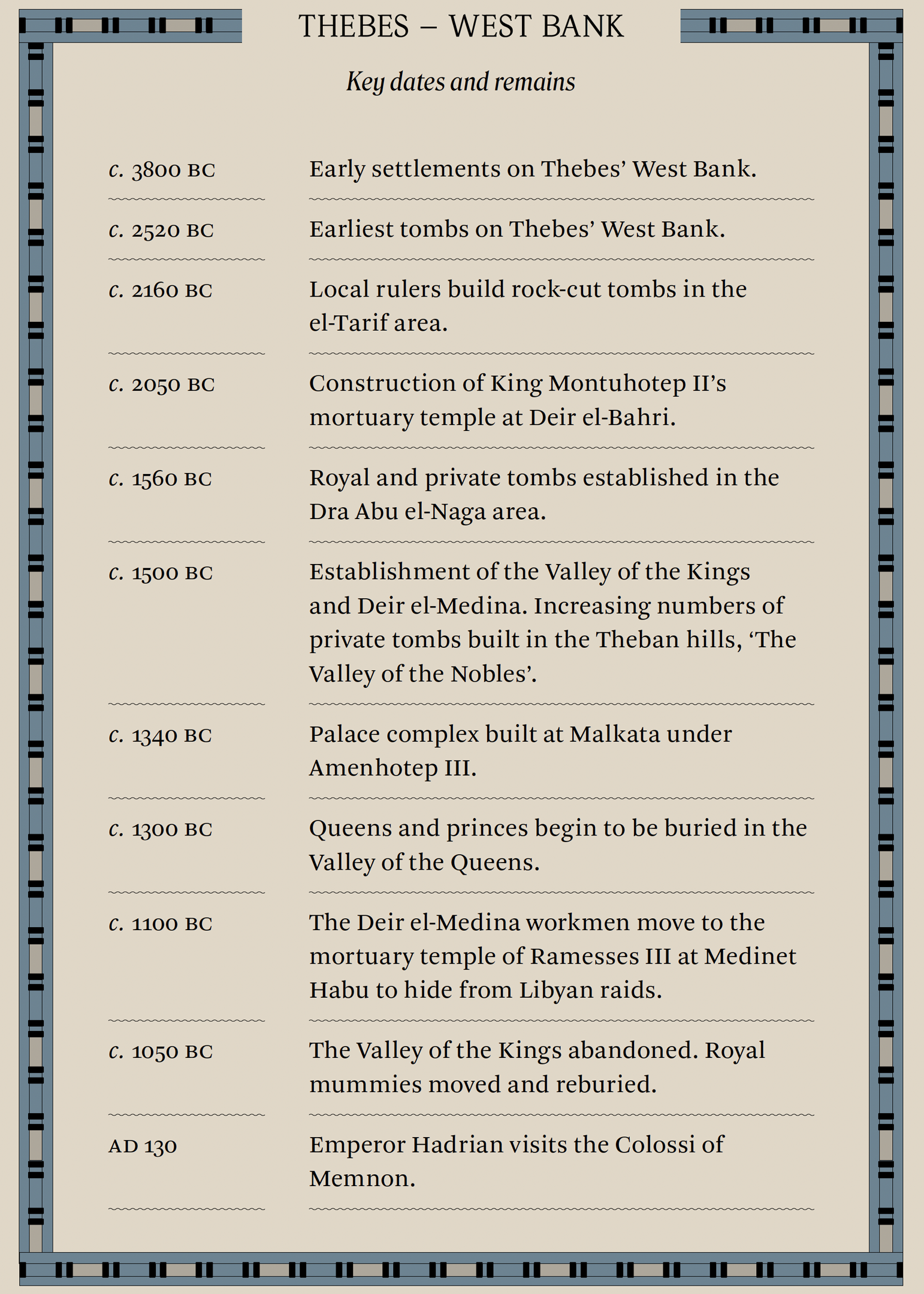

Thebes’ West Bank in history and today

Relatively little is known about the early history of Thebes' West Bank. Settlements were established from the Predynastic Period and tombs of Old Kingdom date have been found in the el-Tarif and el-Khokha areas. The mortuary temple of King Montuhotep II (r. c. 2066-2014 BC), founder of the Middle Kingdom, at Deir el-Bahri – one of the major monuments on the West Bank – was built under the 11th Dynasty, but only a few tombs have been uncovered from the subsequent 12th Dynasty, when royal attention returned to the north of the country. During the New Kingdom, the West Bank saw the construction of the Valley of the Kings, the royal mortuary temples and the many tombs of the nobles, carved into the Theban hills.

Though the West Bank continued to be less developed than the East, scattered villages existed around the monuments. The most famous is Deir el-Medina, a state-sponsored settlement that housed the artisans who cut and decorated the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and their families. A papyrus from the time of King Ramesses XI (r. c. 1094-1064 BC) describes further villages standing between the mortuary temples of King Seti I at Qurna and King Ramesses III (r. c. 1185-1153 BC) at Medinet Habu. The settlement around Medinet Habu was called Maiunehes, where around 1,000 people - mainly administrators and priests - lived in 155 houses. Other houses were spread between the temples, and tenant farmers lived along the cultivation.

Towards the end of the New Kingdom, royal power waned and Thebes fell victim to repeated attacks by Libyan groups. As the situation worsened, desperate – or opportunistic – people started plundering tombs and trading their treasures, leading to official investigations, trials and executions. General Piankh installed himself as high priest of Amun at Thebes and vizier, uniting military, bureaucratic and religious authority in himself. Faced only with a weak pharaoh in the north, he effectively separated the Theban region from the rest of the kingdom, creating an independent province. Tomb robbery, this time officially sanctioned, now began again in earnest. Priests reburied the New Kingdom royals in hidden caches, and 'recycled' the treasures they found, boosting the wealth of Thebes and funding Piankh's military campaigns.

Over the following centuries, Thebes reunited with the rest of Egypt and tombs continued to be built on the West Bank. Under the Ptolemies and Romans, the area became a tourism hot spot, with visitors particularly enamoured by the Colossi of Memnon – two huge statues that stood in front of the mortuary temple of King Amenhotep III (r. c. 1388-1348 BC) – and the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Many tourists left Greek and Latin graffiti on the monuments. The rise of Christianity led to the construction of monasteries, for example at Deir el Bahri, though these closed after the arrival of Islam. Some early Christian communities lived in the ancient tombs. European investigations of the West Bank's ancient monuments began in the late 18th century, and magnified over subsequent decades as collectors and museums competed to make the most impressive discoveries for shipment back to their home countries. Today, the economy of Luxor's West Bank relies on tourism and agriculture •

This excerpt was originally published November 19, 2021.

Egyptian Mythology: A Traveller's Guide from Aswan to Alexandria

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 14 October 2021

RRP: £16.99 | 272 pages | ISBN: 978-0500252284

“This ambitious work clearly demonstrates the amazing complexity of Egyptian myth, legend, literature and belief” – Ancient Egypt Magazine

Join Egyptologist Garry J. Shaw on a tour up the Nile, through a beautiful and fascinating landscape populated with a rich mythology: the stories of Horus, Isis, Osiris, and their enemies and allies, tales of vengeance, tragedy, and fantastic metamorphoses.

The myths of ancient Egypt have survived in fragments of ancient hymns and paintings on the walls of tombs and temples, spells inked across coffins and stories scrawled upon scrolls. Shaw not only retells these stories with his characteristic wit, but also reconnects them to the temples and monuments that still stand today, offering a fresh look at the most visited sites in Egypt.

Shaw’s evocative descriptions of the ancient ruins will transport you to another landscape – including the magnificent sites of Dendera, Tell el-Amarna, Edfu, and Thebes. At each site, discover which gods or goddesses were worshipped there, as well as the myths and stories that formed the backdrop to the rituals and customs of everyday life. Each chapter ends with a potted history of the site, as well as tips for visiting the ruins today. Illustrations throughout bring to life the creation of the world and the nebulous netherworld, the complicated relationships between fickle gods, powerful magicians and pharaohs, and eternal battles on a cosmic scale. This is the perfect companion to the myths of Egypt and the gods and goddesses that shaped its ancient landscape.

“Shaw has made this the perfect companion to exploring the sites of Egypt by putting them in context with the myths of Egypt and the gods and goddesses that shaped its ancient landscape. His witty style also makes it easy to read and enjoy. A highly recommended read.”

– Timeless Travels

“An informative and practical guide to in-person travel … the beautiful presentation and well-researched but succinct approach also makes this a perfect companion for the armchair tourist.”

– British Museum Magazine

Further Reading

Garry: Here are some book suggestions to help you deepen your knowledge of ancient Egyptian religion and mythology:

⇲ Egyptian Magic, The Quest for Thoth’s Book of Secrets by Maarten J. Raven (The American University in Cairo Press; 1st edition, June 2012)

⇲ The Egyptian Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends by Garry J. Shaw (Thames and Hudson; Illustrated edition, March 2014)

⇲ The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry by William Kelly Simpson (Yale University Press; 3rd edition, November 2003)

Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE by Françoise Dunand, Christiane Zivie-Coche and David Lorton (Cornell University Press; Illustrated edition, May 2004)

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many by Eric Hornung and John Baines (Cornell University Press; 1st edition, October 1996)

The Priests of Ancient Egypt by Serge Sauneron, David Lorton and Pierre Corteggiani (Cornell University Press; Illustrated edition, May 2000).

More

Ancient Egypt & Tutankhamun with Garry J. Shaw (c.1335 BC)

Tutankhamun. That one name is enough to conjure up enticing images of Ancient Egypt: dashing chariots, mighty temples, skiffs sailing on the Nile and, most of all, Tutankhamun’s own transfixing Golden Mask. But who really was this figure who has come to represent so much? In this episode of the hit history podcast Travels Through Time, Egyptologist Garry J. Shaw takes us back to the age of Tutankhamun to find out.

With thanks to Caitlin Kirkman and Thames & Hudson. Graphics reproduced with kind permission of Thames & Hudson.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store