Excerpt: A Thousand Golden Cities

‘Description of Kabul’ from Bāburnāma by Bābur

For centuries writers have been enchanted by the place we call Afghanistan. In a newly published book A Thousand Golden Cities: 2,500 Years of Writing from Afghanistan and its People, the author Justin Marozzi has assembled a glittering collection of pieces – written by figures ranging from Pliny to William Dalrymple – that seek to describe and capture the essence of the mountain kingdom.

Here Marozzi introduces us to one captivating piece. It is taken from that ‘dazzling literary jewel’, the Bāburnāma, the sixteenth century memoirs of Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn Muhammad Bābur, the founder of the mighty Mughal Empire.

With a foreword by Justin Marozzi, editor of A Thousand Golden Cities

From his diminutive capital of Kabul, Bābur ‘The Tiger’ (1483–1530), great-great-great-grandson of Timur, looked south for his conquests and founded the long-lived Mughal Empire that would transform the Indian subcontinent and endure until 1857. As ambitious with the pen as he was with his sword, Bābur is widely loved as the author of the Bāburnāma, one of the greatest treasure troves of Muslim literature.

Here is the bristling, infectious humanity of a pioneering, genre-bending warrior-poet-king, an opium-eating, hashish-smoking, wine-drinking, chess-playing diarist, gardener and calligrapher. Bābur’s effervescent prose reveals a fully three-dimensional man – ‘the most completely revealed individual of the sixteenth century’, according to one historian. Think Pepys, Tamerlane, Machiavelli and Montaigne rolled into one.

The honest, confessional tone is enormously endearing. Bābur grieves for lost loved ones, is depressed and feels a failure. He writes of the tortured, should-I-or-shouldn’t-I temptations of drinking alcohol for the first time.

You can hear the snow crunch during his tortuous journey back to Kabul from Herat, city of poets, in the freezing winter of 1506. And both in his long, digressive description of Kabul, and in his much later letter from India to Khwaja Kalan, his governor in the city, you find a man completely entranced by his adopted capital.

With its exuberant tales of wild parties and daring military missions among the mountains, this high-spirited autobiography represents a thrilling counterpoint to the view, widespread in the West, that Islam is monolithic, austere and intolerant. The Bāburnāma is the most dazzling literary jewel, a timely and elegant reminder of the early pluralism of the Islamic world.

– Justin Marozzi

'Boundless and infinite is my desire to go to those parts. Matters are coming to some sort of settlement in Hindustan; there is hope, through the Most High, that the work here will soon be arranged. This work brought to order, God willing! my start will be made at once.' — Bābur in a letter to Khwaja Kalan

For full references and notes please consult the published book

Products and climate of Kabul

In the country of Kabul, there are hot and cold districts close to one another. In one day, a man may go out of the town of Kabul to where snow never falls, or he may go, in two sidereal hours, to where it never thaws, unless when the heats are such that it cannot possibly lie.

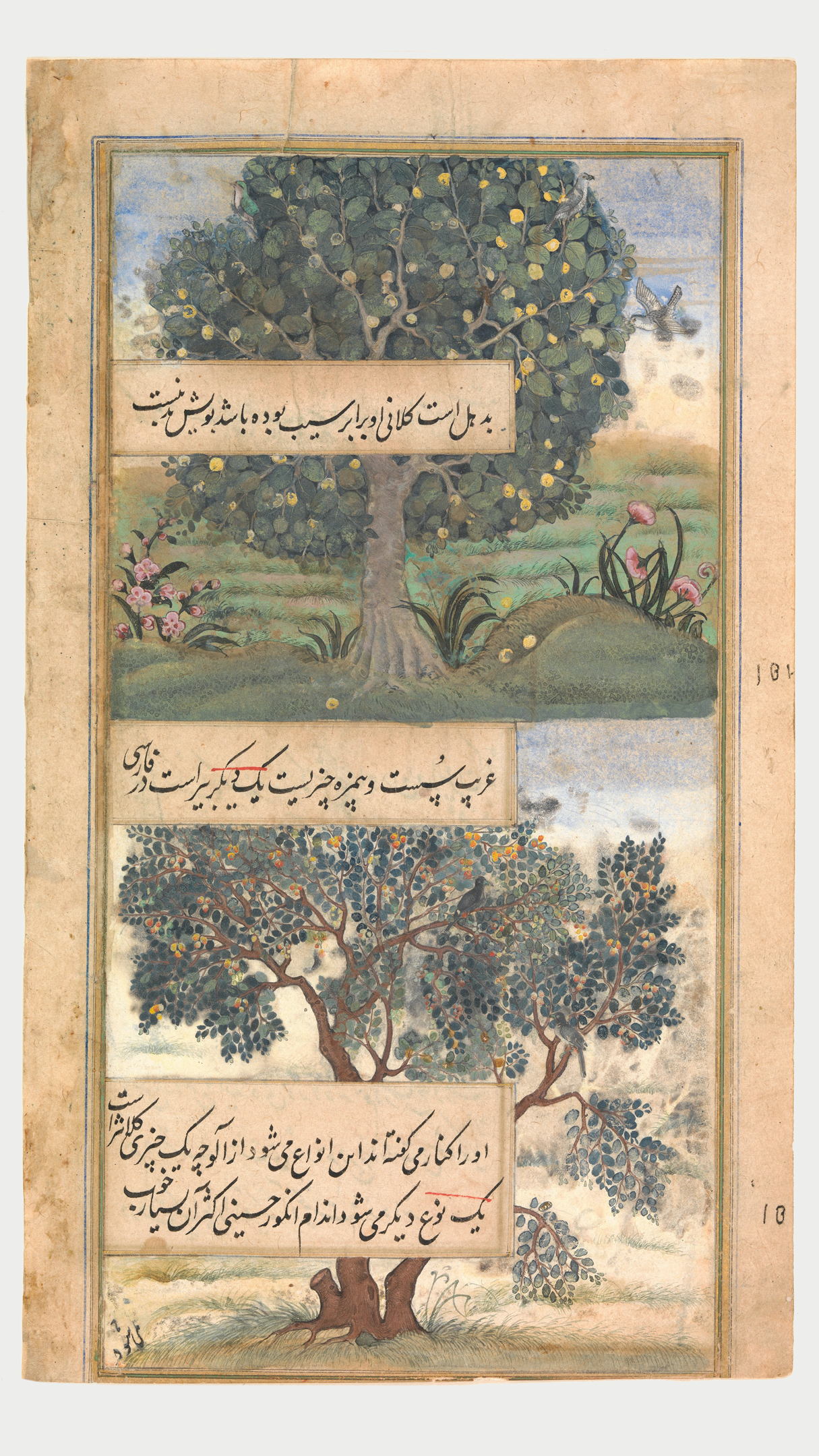

Fruits of hot and cold climates are to be had in the districts near the town. Amongst those of the cold climate, there are had in the town the grape, pomegranate, apricot, apple, quince, pear, peach, plum, sinjid, almond and walnut. I had cuttings of the alu-balu brought there and planted; they grew and have done well. Of fruits of the hot climate people bring into the town;—from the Lamghanat, the orange, citron, amluk (diospyrus lotus), and sugar-cane; this last I had had brought and planted there;—from Nijr-au (Nijr-water), they bring the jil-ghuza, and, from the hill-tracts, much honey. Bee-hives are in use; it is only from towards Ghazni, that no honey comes.

The rhubarb of the Kabul district is good, its quinces and plums very good, so too its badrang; it grows an excellent grape, known as the water-grape. Kabul wines are heady, those of the Khwaja Khawand Sa’id hill-skirt being famous for their strength; at this time however I can only repeat the praise of others about them:—

The flavour of the wine a drinker knows;

What chance have sober men to know it?

Kabul is not fertile in grain, a four or five-fold return is reckoned good there; nor are its melons first-rate, but they are not altogether bad when grown from Khurasan seed.

It has a very pleasant climate; if the world has another so pleasant, it is not known. Even in the heats, one cannot sleep at night without a fur-coat. Although the snow in most places lies deep in winter, the cold is not excessive; whereas in Samarkand and Tabriz, both, like Kabul, noted for their pleasant climate, the cold is extreme.

Fire-wood of Kabul

The snow-fall being so heavy in Kabul, it is fortunate that excellent fire-wood is had near by. Given one day to fetch it, wood can be had of the khanjak (mastic), bilut (holm-oak), badamcha (small-almond) and qarqand. Of these khanjak wood is the best; it burns with flame and nice smell, makes plenty of hot ashes and does well even if sappy.

Holm-oak is also first-rate fire-wood, blazing less than mastic but, like it, making a hot fire with plenty of hot ashes, and nice smell. It has the peculiarity in burning that when its leafy branches are set alight, they fire up with amazing sound, blazing and crackling from bottom to top. It is good fun to burn it. The wood of the small-almond is the most plentiful and commonly-used, but it does not make a lasting fire. The qarqand is quite a low shrub, thorny, and burning sappy or dry; it is the fuel of the Ghazni people.

Fauna of Kabul

The cultivated lands of Kabul lie between mountains which are like great dams to the flat valley-bottoms in which most villages and peopled places are. On these mountains kiyik and ahu are scarce. Across them, between its summer and winter quarters, the dun sheep, the arqarghalcha, have their regular track, to which braves go out with dogs and birds to take them. Towards Khurd-kabul and the Surkh-rud there is wild-ass, but there are no white kiyik at all; Ghazni has both and in few other places are white kiyik found in such good condition.

In the heats the fowling-grounds of Kabul are crowded. The birds take their way along the Baran-water. For why? It is because the river has mountains along it, east and west, and a great Hindu-kush pass in a line with it, by which the birds must cross since there is no other near. They cannot cross when the north wind blows, or if there is even a little cloud on Hindu-kush; at such times they alight on the level lands of the Baran-water and are taken in great numbers by the local people. Towards the end of winter, dense flocks of mallards (aurduq) reach the banks of the Baran in very good condition. Follow these the cranes and herons, great birds, in large flocks and countless numbers.

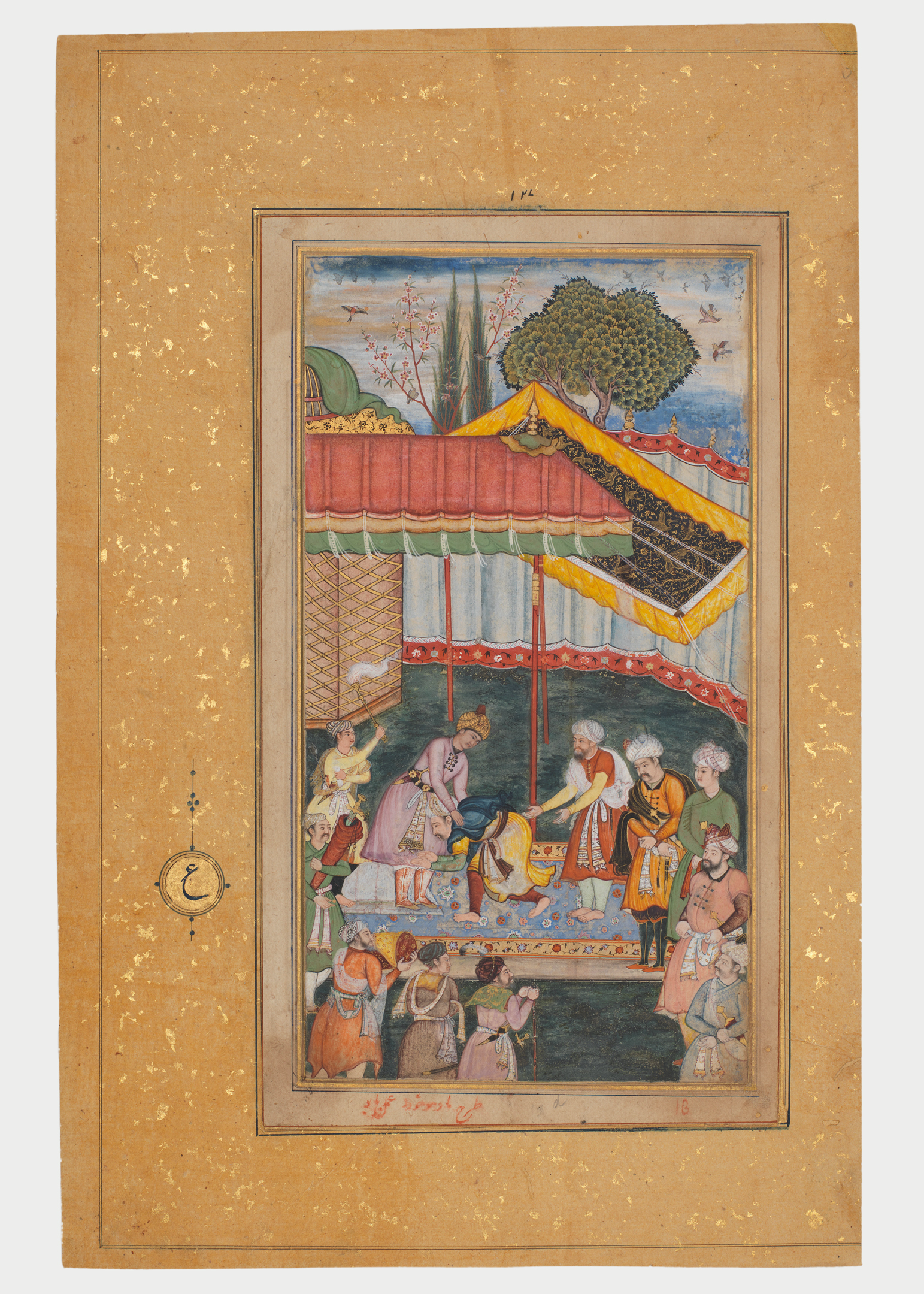

March 5th, 1519

Next morning when the Court rose, we rode out for an excursion, entered a boat and there drank ’araq. The people of the party were Khwaja Dost-khawand, Khusrau, Mirim, Mirza Quli, Muhammadi, Ahmadi, Gadai, Na’man, Langar Khan, Rauh-dam, Qasim-i-’ali the opium-eater,Yusuf-i-’ali and Tingri-quli.

Towards the head of the boat there was a talar [platform] on the flat top of which I sat with a few people, a few others fitting below. There was a sitting-place also at the tail of the boat; there Muhammadi, Gadai and Na’man sat. ’Araq was drunk till the Other Prayer when, disgusted by its bad flavour, by consent of those at the head of the boat, ma’jun [hashish-based mixture] was preferred.

Those at the other end, knowing nothing about our ma’jun drank ’araq right through. At the Bed-time Prayer we rode from the boat and got into camp late. Thinking I had been drinking ’araq Muhammadi and Gadai had said to one another, "Let’s do befitting service," lifted a pitcher of ’araq up to one another in turn on their horses, and came in saying with wonderful joviality and heartiness and speaking together, "Through this dark night have we come carrying this pitcher in turns!"

Later on when they knew that the party was (now) meant to be otherwise and the hilarity to differ, that is to say, that [there would be that] of the ma’jun band and that of the drinkers, they were much disturbed because never does a ma’jun party go well with a drinking-party. Said I, "Don’t upset the party! Let those who wish to drink ’araq, drink ’araq; let those who wish to eat ma’jun, eat ma’jun. Let no-one on either side make talk or allusion to the other."

Some drank ’araq, some ate ma’jun, and for a time the party went on quite politely. Baba Jan the qabuz-player had not been of our party (in the boat); we invited him when we reached the tents. He asked to drink ’araq. We invited Tardi Muhammad Qibchaq also and made him a comrade of the drinkers. A ma’jun party never goes well with an ’araq or a wine-party; the drinkers began to make wild talk and chatter from all sides, mostly in allusion to ma’jun and ma’junis.

Baba Jan even, when drunk, said many wild things. The drinkers soon made Tardi Khan mad-drunk, by giving him one full bowl after another. Try as we did to keep things straight, nothing went well; there was much disgusting uproar; the party became intolerable and was broken up.

Letter to Khwaja Kalan, Babur’s governor in Kabul – date unknown

“After saying ‘Salutation to Khwaja Kalan’, the first matter is that Shamsu’d-din Muhammad has reached Etawa, and that the particulars about Kabul are known.”

“Boundless and infinite is my desire to go to those parts. Matters are coming to some sort of settlement in Hindustan; there is hope, through the Most High, that the work here will soon be arranged. This work brought to order, God willing! my start will be made at once.”

“How should a person forget the pleasant things of those countries, especially one who has repented and vowed to sin no more? How should he banish from his mind the permitted flavours of melons and grapes? Taking this opportunity, a melon was brought to me; to cut and eat it affected me strangely; I was all tears!”

“The unsettled state of Kabul had already been written of to me. After thinking matters over, my choice fell on this:—How should a country hold together and be strong, if it have seven or eight Governors? Under this aspect of the affair, I have summoned my elder sister (Khan-zada) and my wives to Hindustan, have made Kabul and its neighbouring countries a crown-domain, and have written in this sense to both Humayun and Kamran.

Let a capable person take those letters to the Mirzas. As you may know already, I had written earlier to them with the same purport. About the safe-guarding and prosperity of the country, there will now be no excuse, and not a word to say. Henceforth, if the town-wall be not solid or subjects not thriving, if provisions be not in store or the Treasury not full, it will all be laid on the back of the inefficiency of the Pillar-of-the State.”

“The things that must be done are specified below; for some of them orders have gone already, one of these being, ‘Let treasure accumulate.’

The things which must be done are these:—First, the repair of the fort; again:—the provision of stores; again:—the daily allowance and lodging of envoys going backwards and forwards; again:—let money, taken legally from revenue, be spent for building the Congregational Mosque; again:—the repairs of the Karwan-sara (Caravan-sarai) and the Hot-baths; again:—the completion of the unfinished building made of burnt-brick which Ustad Hasan ’Ali was constructing in the citadel.

Let this work be ordered after taking counsel with Ustad Sl. Muhammad; if a design exist, drawn earlier by Ustad Hasan ’Ali, let Ustad Sl. Muhammad finish the building precisely according to it; if not, let him do so, after making a gracious and harmonious design, and in such a way that its floor shall be level with that of the Audience-hall; again:—the Khwurd-Kabul dam which is to hold up the But-khak-water at its exit from the Khwurd-Kabul narrows; again:—the repair of the Ghazni dam;1 again:—the Avenue-garden in which water is short and for which a one-mill stream must be diverted; again:—I had water brought from Tutum-dara to rising ground south-west of Khwaja Basta, there made a reservoir and planted young trees.

The place got the name of Belvedere, because it faces the ford and gives a first-rate view. The best of young trees must be planted there, lawns arranged, and borders set with sweet-herbs and with flowers of beautiful colour and scent; again:—Sayyid Qasim has been named to reinforce thee; again:—do not neglect the condition of matchlockmen and of Ustad Muhammad Amin the armourer; again:—directly this letter arrives, thou must get my elder sister (Khan-zada Begim) and my wives right out of Kabul, and escort them to Nil-ab.

However averse they may still be, they most certainly must start within a week of the arrival of this letter. For why? Both because the armies which have gone from Hindustan to escort them are suffering hardship in a cramped place, and also because they are ruining the country.”

“Again:—I made it clear in a letter written to ’Abdu’l-lah that there had been very great confusion in my mind, to counterbalance being in the oasis of penitence. This quatrain was somewhat dissuading:—

Through renouncement of wine bewildered am I;

How to work know I not, so distracted am I;

While others repent and make vow to abstain,

I have vowed to abstain, and repentant am I.

A witticism of Banai’s came back to my mind:—One day when he had been joking in ’Ali-sher Beg’s presence, who must have been wearing a jacket with buttons, ’Ali-sher Beg said, ‘Thou makest charming jokes; but for the buttons, I would give thee the jacket; they are the hindrance.’ Said Banai, ‘What hindrance are buttons? It is button-holes that hinder.’ Let responsibility for this story lie on the teller! Hold me excused for it; for God’s sake do not be offended by it.

Again: that quatrain was made before last year, and in truth the longing and craving for a wine-party has been infinite and endless for two years past, so much so that sometimes the craving for wine brought me to the verge of tears. Thank God! this year that trouble has passed from my mind, perhaps by virtue of the blessing and sustainment of versifying the translation. Do thou also renounce wine! If had with equal associates and boon-companions, wine and company are pleasant things; but with whom canst thou now associate? with whom drink wine? If thy boon-companions are Sher-i-ahmad and Haidar-quli, it should not be hard for thee to forswear wine. So much said, I salute thee and long to see thee.” ■

A Thousand Golden Cities: 2,500 Years of Writing from Afghanistan and its People

Apollo, 16 November, 2023

RRP: £30.00 | 720 pages | ISBN: 978-1803285351

In the Western mind, Afghanistan has come to mean many things in recent decades, most of them bad. Partly thanks to the relentless media coverage of the "War on Terror", it has become synonymous above all with war and terrorism - from the Taliban to Al Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State - crushing levels of poverty and immiseration. In ways which would have been familiarto both Herodotus in the fourth century BC and Ibn Khaldun in the fourteenth AD, it has also come to represent the latest testing ground for imperial hubris and over-expansion, another tomb in the "graveyard of empires".

This is an extraordinarily reductive and one-dimensional portrait of a nation. Afghanistan is, and always has been, vastly more interesting than that. Its long and tumultuous history at the centre of the world, at the heart of cultural exchanges between East and West, encompasses high culture, low politics, domestic dynasties, international adventures, Great Power rivalry and a completely compelling vein of skulduggery.

This anthology will celebrate this rich, engrossing heritage with a captivating blend of history and geography, religion and culture, politics and poetry, drama and memoir, home-grown fiction and the self-serving literature of invaders. It will celebrate Afghan voices as much as those of foreigners who, for better or worse, have been bewitched by this staggeringly beautiful mountain kingdom.

"Thoroughly good fun ... the narration moves swiftly but gracefully from episode to episode." — Sunday Times

"This book delivers drama through sublime writing, but mainly through marvellous images... as sharp as the Arabian desert in the midday sun." — Gerard DeGroot, The Times

"An excellent prelude to Marozzi's previous books." — Spectator

Additional Credit

With thanks to Kate Wands