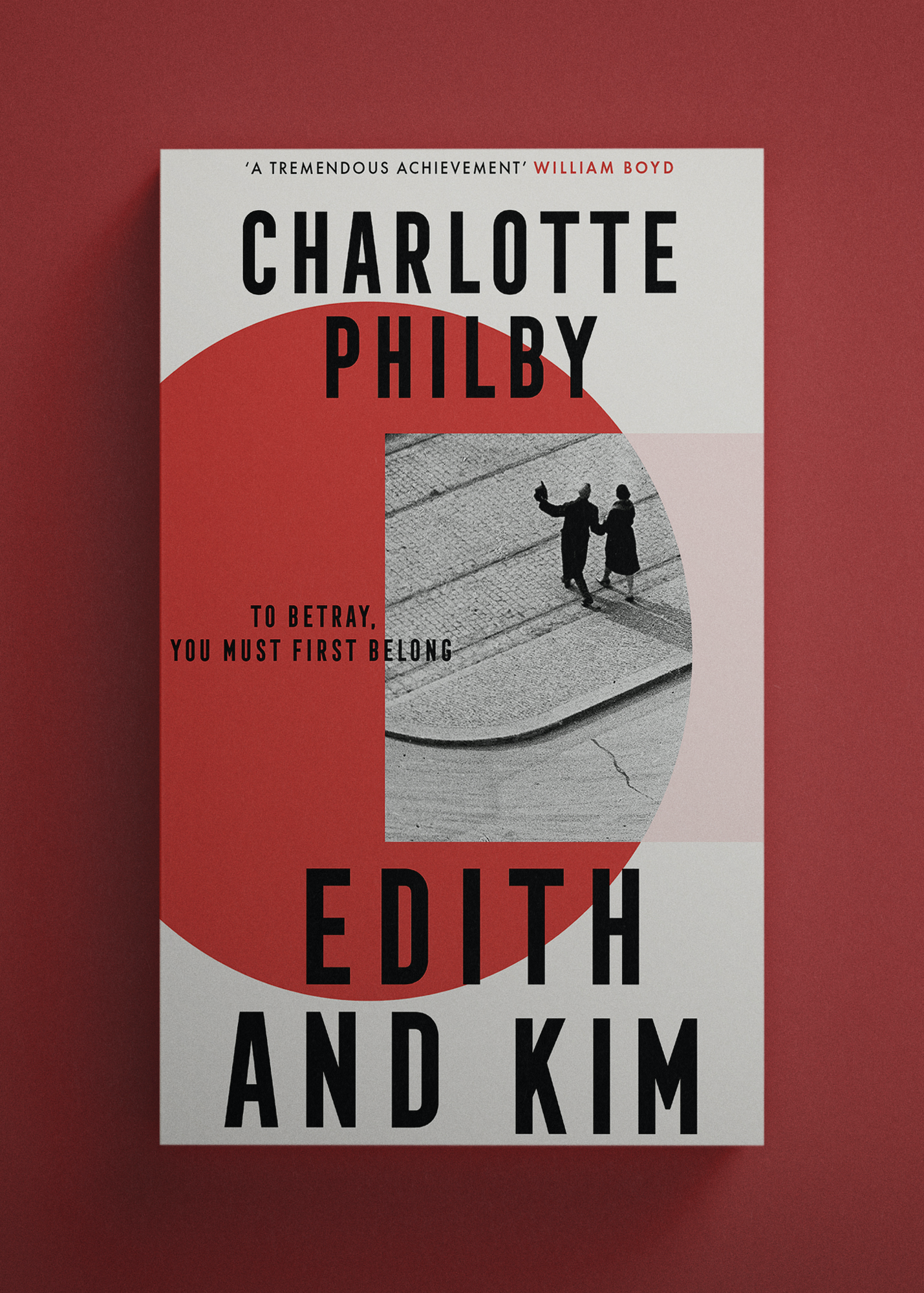

Excerpt: Edith and Kim by Charlotte Philby

To Betray, You Must First Belong

Edith and Kim is a poignant and captivating fictional reconstruction of one of the most important relationships of interwar espionage history. In June 1934, Kim Philby met his Soviet handler, the spy Arnold Deutsch. The woman who introduced them was called Edith Tudor-Hart. She changed the course of 20th century history. Then she was written out of it.

Drawing on the Secret Intelligence Files on Edith Tudor-Hart, along with the private archive letters of Kim Philby, this finely worked, evocative and beautifully tense novel – by the granddaughter of Kim Philby – tells the story of the woman behind the Third Man.

Foreword by Charlotte Philby

There have been countless books written about the double agent Kim Philby, often with conflicting views on the hows and the whys and, indeed, the whos. Far fewer have been written about Edith Tudor-Hart, the woman who recruited him, referred to in British intelligence files as ‘the foreign woman’.

What follows is not meant as a comprehensive retelling of a highly contentious period, but a work of fiction based on the facts as I have variously found them, reimagining the lives of two people from starkly different backgrounds whose very existences transformed one another’s, and changed the course of history.

While much of this story is true, ⇲ Edith and Kim is a novel. In pulling together strands of the principal characters’ lives, I have chosen to exclude certain family members and friends on both sides, either because it didn’t feel fair or right to include them, or simply because they didn’t serve the version of events as I have reconstructed it. Some characters in the story are entirely invented.

— Charlotte Philby

London, June 1934

An abridged excerpt from Edith and Kim by Charlotte Philby

The journey from Marble Arch to Regent’s Park takes longer than it should.

Despite the morning sun, the woman wears a dark turtleneck and long skirt, a beret pulled down over bobbed hair. She moves quickly, sticking to the shadows. The man, a few years her junior, keeps pace, his hands pushed deep into the pockets of his overcoat, the bit of his pipe clenched between his teeth.

There is a portentous quality to the silence as they turn into Hyde Park, the scuffling of horse-hooves closing in from behind causing him to clench his fists until the sound passes, the morning riders kicking up dust as they skirt the perimeter.

A bead of sweat forms on his forehead as they turn left, away from the grass, and cross Park Lane. The streets that slice through Mayfair are blessedly shaded as they continue their walk for an hour or so, along New Bond Street and Shaftesbury Avenue, the woman’s eyes focused ahead but alert to every sound as the city comes to life: peals of laughter from a young couple bursting out from a doorway, the clatter of a rag-and-bone man fading into the echoes of a thousand muted voices, layered over one another across the city’s streets.

Somewhere near Aldwych she hails a taxi, the man ducking in beside her, a ripple of electricity passing between them, along with unspoken questions, as his hand accidentally brushes hers.

London skids past on the other side of the glass, the two passengers facing away from one another, their attention fixed on the scenes playing out on their respective sides of the street as they head back the way they came: children skipping behind impatient parents; lovers walking arm-in-arm, locked in their own private world, faces tipped upwards like buttercups in the morning rays. A doorman outside the Ritz adjusts his cufflinks as they roll back along Piccadilly, stifling a yawn, his eyes flicking up, suddenly aware that he is being watched.

The couple inside the motor-car sit in silence until, after a while, the woman leans forward and asks the driver to stop.

The response to her distinct Austrian lilt is an immediate slowing of wheels. She steps out and the man follows her, their footsteps weaving an invisible web. A while later still, she holds her arm out again, flagging down another passing cab; this time her companion pauses, raising his hand to his pipe, opening his mouth as if to speak.

But the words fall away as he steps in behind her, one of them the spider, the other the fly.

By the time they reach Maida Vale tube station more than two hours have passed.

The sound of their own footsteps follows as they take the stairs to the platform. It is cooler down here, below ground.

The man bristles with nervous energy as the train approaches; a rat scuttles across the tracks and disappears into the black. The woman boards first, her companion stepping in behind, his thoughts turning briefly to his mother and father far from home, somewhere on the other side of the world.

Home. The word comes to her as they stand side by side in the carriage, and she lets it roll a moment in her mind, her thoughts tilting this way and that, unable to find a flat surface on which to land.

‘I do beg your pardon.’ The passenger seems to appear from nowhere, catching her eye momentarily as he squeezes past, touching the brim of his hat. Without warning, as the doors start to close, the woman takes her companion’s hand and pulls him out of the carriage, leading him across the empty concourse to the opposite platform where another train hurtles towards them, the sound of the brakes escalating into a scream.

It is only once they are on the path cutting through Regent’s Park, some four hours after they set off, that the man finally speaks.

‘He is expecting us?’

The woman says nothing in reply, only slowing slightly, allowing her charge to move ahead as they catch sight of a figure on the bench: short, stocky frame, boxer’s ears partly obscured beneath a hat.

Alert to their footsteps, the man looks up.

Instinctively the younger man, out of breath from all the walking, takes the pipe from his lips, turning briefly towards his chaperone. But she has already gone.

The Fact of Who I Was

One of Edith Suschitzky’s most formative memories is her father’s first arrest, though she wasn’t there. It isn’t possible, some would say, to recall an event one hasn’t witnessed. But Edith Suschitzky lived with that day, on a loop, either regaled to her as a medal of defiance over family lunches, or whispered into her ear at night as she fell asleep, as a warning: Never let them break you. They will never let you be free. When you grow up with a story, the way she has grown up with this one, it becomes partly your own.

The story of that day in 1920, not long after her twelfth birthday, at the bookshop at Favoritenstrasse 57, refracts in Edith’s memory, parts of it growing more or less vivid with every retelling. On some days, she focuses on the smell of diesel and yeast carried on the air from the bakers along the street as the shop door creaks open, her father looking up from the counter, his eyes instantly hardening. On others, she pictures the officer’s shadow obliterating the doorway, homes in on the shine of his boot as he makes his way unhurriedly through the store, his fingers running over the spines.

Both Edith and her brother Wolf – now eight years old – have already headed to school. The fog had risen thick that morning, blanketing the city’s streets, obscuring Wilhelm Suschitzky’s view as he made his way past the brickworks and the row of shops that led to Brüder Suschitzky: the first Socialist bookshop in Vienna’s tenth district of over 120,000 people. These were the exact words he had used to his wife, Adele, the day he and his brother Philipp had first pulled back the doors in the autumn of 1901.

Already, those days felt like another lifetime. Post-war, the world had changed. Life had changed – though not as much as it would, not least for a business which extolled the virtues of enlightenment in one of city’s largest working-class districts, first simply as a bookshop and then, for the past eight years, also as a publisher.

Wilhelm paused that morning, as he did every morning before opening up, to take in the shop and its evidence of a life’s work: the original sign, BUCHHANDLUNG ANTIQUARIAT, now hanging alongside a second sign advertising Anzengruber-Verlag publishers.

From the moment the men had first opened the doors to Brüder Suschitzky almost two decades earlier – long before either of them could have envisaged what fate had in store – it was more than just a business. This was a manifesto for the world the Suschitzky brothers had wanted for the children they were yet to have. A middle-class family choosing to live amidst the poverty and the oppression of the working classes, dirt steeped in a growing sense of despair, the Suschitzky brothers – and their books – were consciously paraded as a bastion of hope.

It was this hope, Wilhelm would tell his daughter, soberly, as he stroked her hair at night, that the officials were trying to shut down when they came and seized the tomes and leaflets, novels and texts, from workers’ poetry to tracts on the women’s movement, pedagogical reform and sexual emancipation. That first time – the officers storming through their shop, trampling not just the carpet but the very fabric of their lives – was the ultimate act of aggression. And yet, Wilhelm would recall, repeating the events of that day as one might a lullaby, seeing those men there in their perfectly pressed clothes, their well-fed bellies moving self-righteously through the world he and his brother had created, he hadn’t cowered. Rather, Edith’s father had felt himself stand taller. A self-proclaimed pacifist, he hadn’t lashed out. He had refused to fight in a way against which they could have immediately retaliated.

But he never stopped fighting in the years that followed, as the harassment escalated along with the confiscation of books, the court trials worsening as Austria’s democratic government fell. Wilhelm Suschitzky fought quietly – he fought with his mind, he would tell Edith, proudly. And he never stopped fighting. Right up until the moment he held a gun to his own head.

When she was ten years old, Edith Suschitzky had pursued an argument with her father over supper as he condemned the attempted coup d’état by the newly formed KPÖ, the Communist Party of Austria, claiming that violence was not the answer, that it undermined the efforts that men like him had been making for years. (Men, she noted.) It wasn’t simply that she disagreed, she replied – more horrifying was the fact that someone she loved so dearly could think so strangely. A man who had seen with his own eyes the bodies floating in the Danube.

‘Books and ideas alone aren’t enough,’ she had chastised Wilhelm in no uncertain terms. ‘You can’t feed a dying man with thoughts.’

‘Your voice,’ he had snorted, marvelling at her passion. ‘It teeters at the edge of some terrible catastrophe. You are just a child, you cannot understand.’

But she did understand, innately, and with a received wisdom gathered over the weekends spent in Grundlsee; she felt it, vibrating through the words of the scholars at the camp organised by Eugenie Schwarzwald, sorrow hovering over the brushstrokes of the artists she met there, resonating through the semi-quavers and crotchets of composer Arnold Schoenberg as he taught. She understood in a way that, once acknowledged, was impossible for her to ignore.

Change requires action.

‘Father, for an atheist,’ she replied, ‘you do love to preach.’

‘Preach on, St John.’

This is as much as the boy hears before the men’s voices lower again so that Kim cannot decipher the rest of the conversation, beyond the odd snatched words: Hashemites and Gertrude Bell.

Not that it is of much interest anyway. The child’s eavesdropping is little more than a way to pass the time until his father’s attention is – if only briefly – his again.

Looking about him, Kim strains his eyes to adjust to the brightness of the sun, which burns as hot as tar, its harsh glare stretching across the sky and the endless dust beneath their feet, bouncing off the stone of the building’s archway, where they now stand.

He has not long since stepped off the plane from London, and the Trans Jordan heat prickles at his skin – though he won’t show his discomfort.

Despite his weariness, and his thirst, and the increasing need for shade, he works hard to hold himself straight as his father talks to the other man, to whom the child has not been introduced. ‘You know you shouldn’t be listening.’

The voice startles him. When he turns, he is greeted by a plump young woman with blonde curls and an amused, precocious smile.

‘I wasn’t,’ the boy replies, his cheeks colouring, the words And you should not creep up on people sticking to the back of his throat.

‘That’s my father, talking to yours. Your name’s Kim, isn’t it?’

Kim turns away from her, slightly, regarding the heavy black beard and white robes, his father’s appearance growing more swarthy and unkempt with every moment that has passed since he was sent to the Emir Abdullah as chief British representative, two years earlier, following a short spell in Baghdad where – so the boy has gleaned – he made no secret of being in favour of a republic rather than a monarchy.

‘Yes, St John is my father,’ Kim says, pulling himself upright.

Something about this woman – the haughty voice and knowing eyes – makes him uncomfortable; and yet he finds himself keen to impress her, working hard to disguise the stutter that occasionally peppers his speech.

‘Kim is a nickname, actually. After the character in my father’s favourite novel—’

‘Kim, the boy with two separate sides to his head... You look surprised – did you imagine I wouldn’t have read Kipling?’

When the boy doesn’t reply, she continues. ‘My father says your father is a very difficult man. He says he is firmly against the policy of the British government.’

‘Well, perhaps that’s because your father lacks the imagination, or the vocabulary, to truly understand a man such as mine.’

She laughs. ‘I like your spirit. My father also says St John is pugnacious. Do you know what that means?’

‘Do you?’

‘Yes. Although English isn’t my first language.’

‘What is?’

‘Russian.’

Kim regards her, his eyes narrowing. ‘Say something to me in Russian, then.’

‘What would you like me to say?’

‘I don’t know. Introduce yourself.’

‘Добрый день, меня зовут Флора Соломон – приятно познакомиться, наглое дитя.’

‘What did you say?’

‘Learn Russian and then you’ll find out.’

‘My father speaks ten languages,’ Kim replies.

‘And what about you?’

He shrugs. ‘I spoke Hindi before I even spoke English. I was born in India – I nearly died when I was a boy. My ayah found a cobra in the bath; if my father hadn’t come along and shot at it, I would be dead.’

‘How very shocking.’

Kim struggles to hold himself upright, feeling the woman consider him, an amused look on her face.

‘I have a son,’ she says. ‘He’s only two years old. How old are you, Kim?’

‘Eleven.’

‘Small for your age, aren’t you?’

‘Not really.’

‘My son is Peter; we live in London. You do, too, don’t you?’

‘18 Acol Road, Hampstead. My father lives here, and I stay in England with my mother and three sisters.’

‘Well, in that case, young Kim, perhaps our paths will cross again.’ The woman smiles, turning away from him.

‘Hey, what’s your name? You never said.’

The woman looks back at him briefly, her expression becoming serious. ‘I did tell you – it’s Flora Solomon – you just weren’t listening.■

Edith and Kim: To Betray, You Must First Belong

The Borough Press, 31 Mar, 2022

RRP: £16.99 | 384 pages | ISBN: 978-0857527622

In June 1934, Kim Philby met his Soviet handler, the spy Arnold Deutsch. The woman who introduced them was called Edith Tudor-Hart. She changed the course of 20th century history.

Then she was written out of it.

Drawing on the Secret Intelligence Files on Edith Tudor-Hart, along with the private archive letters of Kim Philby, this finely worked, evocative and beautifully tense novel – by the granddaughter of Kim Philby – tells the story of the woman behind the Third Man.

"One of ‘the heirs to John le Carré" – The Times

"Completely fascinating. A sophisticated and brilliantly constructed fictional retelling of a crucial relationship in 20th century espionage history. A tremendous achievement" – William Boyd

"Complex and powerfully written… a persuasive repurposing of the lives of real-life figures" – i Newspaper

Charlotte recommends:

⇲ My Silent War by Kim Philby (Cornerstone, 2018)

"The autobiography held back for years before being published. To be taken with a large pinch of salt, it might be a piece of writing that had to make it through the KGB's editorial system but it is certainly entertaining and well-written."

⇲ Our Bauhaus: Memories of Bauhaus People by Magdalena Droste (Prestel, 2019)

"A brilliantly evocative compendium of stories immortalising the hopes, dreams and anecdotes of original Bauhaus students and teachers, in their own words."

Philby: KGB Masterspy by Phillip Knightley (Carlton Books, 2003)

"Knightley was a journalist for the Sunday Times' Insight team, helping to expose such stories as the Thalidomide scandal. This book is the result of time spent interrogating my grandfather in Moscow. His style is remarkable, and this book is particularly special to me as he became a family friend and gave me some fondly remembered pep talks as an aspiring journalist."

View from a Long Chair by Jack Pritchard (Routledge, 1984)

"Jack Pritchard’s View from a Long Chair is a gorgeous memoir by the Isokon co-founder who created the infamous Lawn Road Flats, a Modernist hot-bed for spies and bed-swapping (and one-time home to Agatha Christie), which is one of the key locations in Edith and Kim. "

Tudor Hart: In the Shadow of Tyranny by Duncan Forbes (Hatje Cantz, 2013)

"A beautiful and informative large-format compendium showcashing Edith's finest photographic work, and drawing a line between various parts of her life, as a photographer, committed Communist and a single mother to a mentally ill child."

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Amy Winchester and HarperCollins UK and The Borough Press. Author photograph © Roo Lewis.