Excerpt: Exiles by William Atkins

A luminous exploration of exile, the people who have experienced it, and the places they inhabit

French anarchist Louise Michel; Zulu prince Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo; Ukrainian revolutionary Lev Shternberg. This is the story of three unheralded nineteenth-century dissidents, whose lives were profoundly shaped by the winds of empire, nationalism and autocracy that continue to blow today.

In Exiles, William Atkins travels to their islands of banishment in a bid to understand how exile shaped them and the people among whom they were exiled. Rendering these figures and the places they were forced to occupy in shimmering detail, Atkins reveals deeply human truths about displacement, colonialism and what it means to have and to lose a home.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories foreword by William Atkins

Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, known simply as ‘Dinuzulu’, is one of the subjects of Exiles: Three Island Journeys. The book tells the story of three late-nineteenth-century political exiles and their islands of banishment, exploring the links between the practice of exile and the practice of empire. As a fierce – and effective – opponent of British colonialism in Zululand, the young king Dinuzulu was banished by the British to St Helena, the tiny remote island in the South Atlantic best known as Napoleon’s place of exile. As I discovered when I visited the island, his legacy, and the legacy of colonialism, persist, beneath the shadow of St Helena’s more famous exile, just as they persist in South Africa.

— William Atkins

Ghost Mountain

An abridged excerpt from Exiles: Three Island Journeys by William Atkins

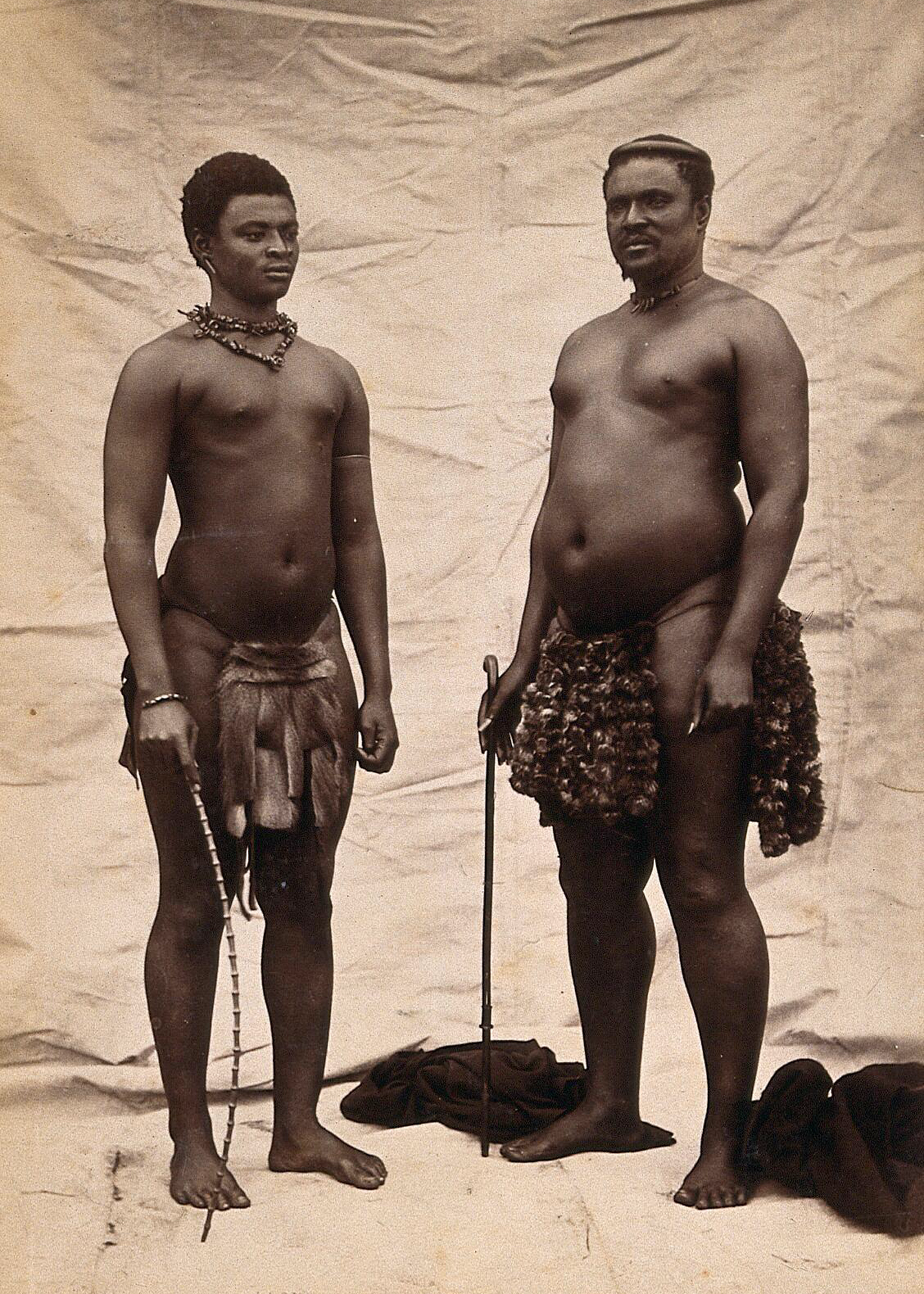

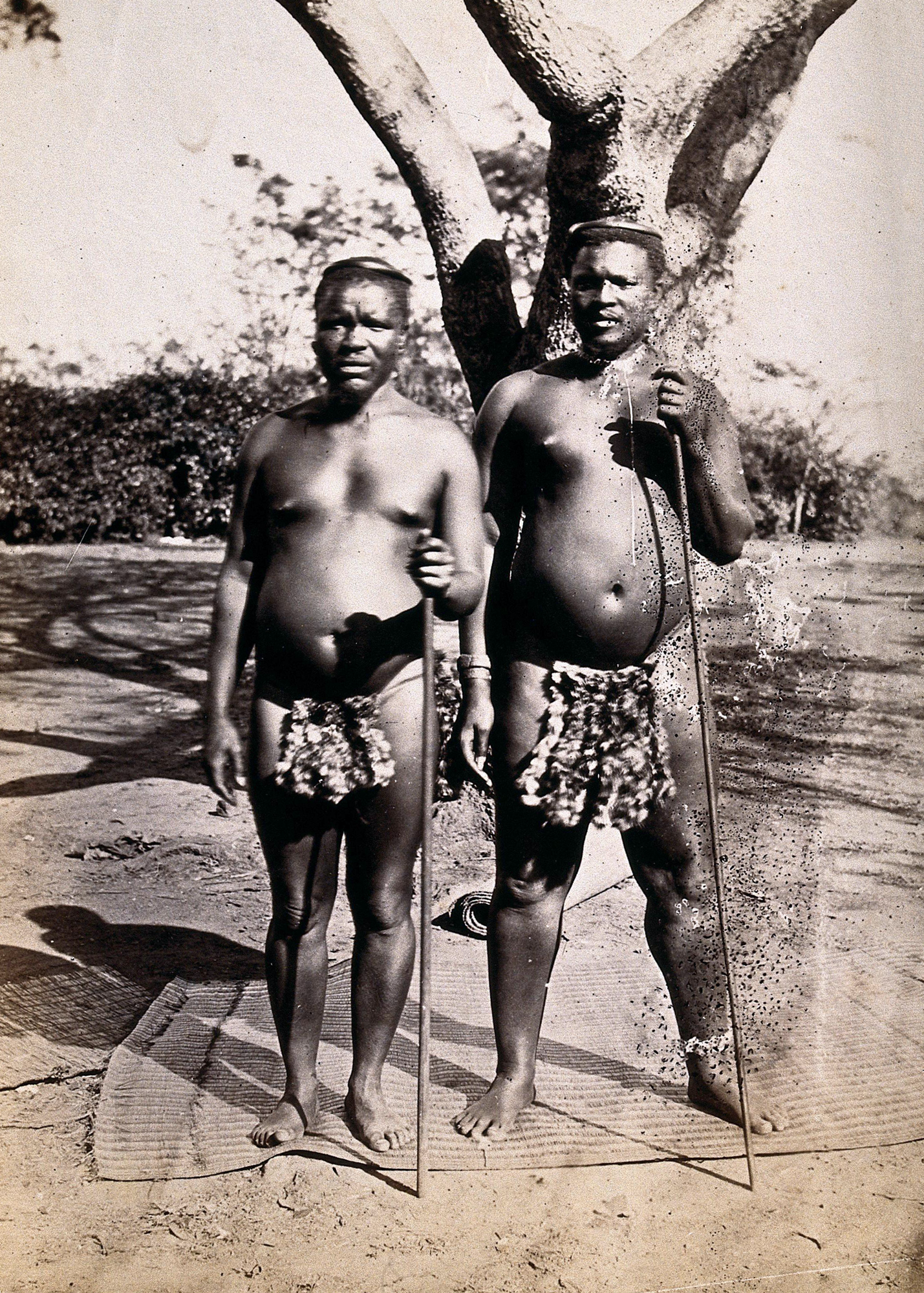

Dinuzulu, Cetshwayo’s son, aged about twenty, at the Pietermaritzburg police barracks in the then British colony of Natal, southeastern Africa. It is November 1888 and he has just been induced to surrender. The photo is a mugshot, but also an ethnographic record, also a trophy. He was born in north-west Zululand, the region from which the nation emerged in the eighteenth century. As a baby he was ‘Mahalena-who-comes from-oNdini’, according to the Zulu historian Magema Fuze. When his father was crowned in 1873, he commissioned the building of a huge umuzi, or royal homestead: oNdini, the nation’s capital. He granted his young son his royal name, Dinuzulu, from either udin’uZulu, ‘he wearies the Zulus’ or, conversely, udinwa nguZulu, ‘he is wearied by the Zulus’. Either way, it seems Cetshwayo had a presentiment of how the boy’s life would turn out.

The new capital, in the dry thorn-bush country of the Mahlabathini Plain, was named to denote its impregnability, oNdini meaning rim or escarpment. It housed several thousand people, as many as 5,000 during feasts and festivals. Elliptical in shape, like most Zulu homesteads, it was ringed by a double palisade, the outer one of sharpened timbers, the inner of rushes.

In its centre was a parade ground where the king inspected his men and where the royal cattle were kept.

The king’s own hut and those of his wives stood in a fenced enclosure at the homestead’s northern edge, while Dinuzulu and his royal sisters slept in the adjoining enclosure. To the rear was a rise from which the king could survey oNdini. To the north was the Hlophekhulu Mountain, source of the spring reserved for his father’s drinking water; to the south, the Mbilane Stream, from which the royal bathwater was drawn, and which, further south, fed into the fuming White Umfolozi. Beyond that river’s far bank, some fifteen miles away, was eMakhosini, the Valley of the Kings, where Dinuzulu’s ancestors, the founders of the Zulu kingdom, are buried.

Death, and the world of the dead, were close. Before the young man, like a meal laid out, was his kingdom by ancestral right, the abode of the amadlozi, spirits of his ancestors, who not only reside in the earth but are synonymous with it. But any safety he felt was to be short-lived, for those five years were the last settled ones he would know. When the British invaded in 1879, under the casus belli of Cetshwayo’s refusal to disband his military regiments, oNdini was destroyed, the royal cattle were seized and more than a thousand Zulus killed. It was partly plain revenge for the shock defeat Cetshwayo’s forces had dealt the British at the Battle of Isandlwana six months earlier, when an army of 20,000 Zulus had killed more than 1,300 British and colonial troops in Britain’s greatest military disaster in nearly a century. ONdini burnt for four days, leaving nothing but potsherds and bones, and the discs of clay, fired hard by the flames, which had once been the floors of the royal huts.

Captured by the British and confined to Cape Town, almost 900 miles from oNdini, his father Cetshwayo was obliged to watch from afar while the Zulu kingdom was partitioned once more, into thirteen chieftaincies.

Cetshwayo’s greatest ally in exile was his friend John Colenso, known to Zulus as Sobantu (‘father of the people’), Bishop of Natal, lifelong irritant to the British, and an outspoken critic of the invasion. His role as thorn in the British side was inherited by his daughter, Harriette. It was through the father and daughter’s insistent petitioning of the government in London that Cetshwayo was finally given leave to make his case to the queen in person.

The first Zulu king to visit Britain, in 1882, he adopted European dress for the occasion – the swagger stick replacing the knobkerry, the three-piece suit replacing the beshu, the top hat covering the isicoco. The press and public in London beheld him with dazzled perplexity. ‘The crowd was so great I was afraid to venture into the street,’ wrote one Londoner. ‘I saw him capitally.’ Cetshwayo’s presence brought home to the London public the reality of Britain’s colonial engagements. If France’s consolidation of its Pacific possessions, such as New Caledonia, had been partly a bid to demonstrate its clout after the ‘humiliation’ of Sedan, then Britain’s tightening grip on south-eastern Africa was in part a competitive reaction to the deutsche Weltpolitik of a Germany newly unified following the Franco-Prussian War.

His outfit was understood to be in the nature of a genuflection; so too was his journey itself. After the briefest of audiences with Queen Victoria at her residence on the Isle of Wight, it was agreed that Cetshwayo would return to Zululand under the terms of a new partition, which saw the consolidation of the nation’s thirteen chiefdoms into three parts: Cetshwayo’s kingdom, much reduced, was sandwiched between a new British Reserve Territory to the south-west and, to the north-east, the enlarged domain of his former subordinate – and now British loyalist – Zibhebhu kaMaphitha, chief of the Mandlakazi branch of the royal family, and a famously formidable military leader. You may return to your kingdom, then, provided you accept it is yours no longer. Cetshwayo’s son, many years later, would be obliged to make a similar concession.

In July 1883, just five months after his return, Cetshwayo’s rebuilt oNdini was destroyed by Zibhebhu’s troops during a surprise nighttime attack. The assault followed the Battle of Msebe, in which Cetshwayo’s brother Ndabuko had led an attack on Zibhebhu’s homestead only to be ambushed by Zibhebhu. Ndabuko lost more than 1,000 men; Zibhebhu, ten. The failure would haunt Ndabuko. At oNdini, fifteen weeks later, along with several of his senior chiefs and advisers, three of Cetshwayo’s wives were killed, and his baby son, Nyoniyentaba (‘mountain bird’), stabbed to death in his mother’s arms. One of Zibhebhu’s British mercenaries remembered the slaughter with the wet-lipped relish of every career killer, particularly the murder of Cetshwayo’s chiefs: ‘Being all fat and big bellied, they had no chance of escape; and one of them was actually run to earth and stabbed to death by one of my little mat bearers.’ Dinuzulu, who was about sixteen, escaped on horseback with his uncle Ndabuko. Cetshwayo, meanwhile, having been injured, fled to the dense mist forest of Nkandla, ancient asylum of Zulu royalty. On 8 February 1884, not long after news reached him of the death of his ‘father’, John Colenso, he too died.

As tradition dictated, the king’s body was wrapped in a bull’s hide and strapped sitting to the central post of a closed hut, to desiccate in the smoke of a fire of aromatic woods. The British resident commissioner, Melmoth Osborn, forbade his burial in the eMakhosini Valley, where the Inkatha yezwe yakwaZulu was kept, the sacred coil of grasses that symbolise Zulu nationhood and unity, whose previous incarnation had been destroyed by the British in 1879. To hold the ceremony there would only encourage unrest, Osborn maintained; and so after two months the king was still above ground.

This was the depth of the white man’s power: to dictate the body’s whereabouts even in death, even as it ceased to be identifiable. While Dinuzulu remained in hiding in Nkandla, Ndabuko was finally allowed to take his brother’s body by ox wagon to the Bhophe Ridge, deep in the forest, where it was buried on 10 April along with the broken-up wagon and the sacrificed oxen.

Cetshwayo had become umuntu oshonileyo, finally, ‘one who has gone down’.

Because his mother, Novimbi Msweli, was a commoner, Dinuzulu carried the taint of illegitimacy. And so when Cetshwayo died there were other contenders to the Zulu chieftaincy, including a half-brother of Dinuzulu’s. His uncle, Ndabuko, and his half uncle, Shingana, eager to validate Dinuzulu’s succession, had been at Cetshwayo’s deathbed. As reported by them, the old king’s dying words were, ‘Mpande, my father, left the country to me; I, Cetshwayo, leave the country to my son Dinuzulu.’ And so Dinuzulu was proclaimed king. But Magema Fuze recorded Cetshwayo’s last words differently: they were spoken not to his brother and half-brother, he maintained, but directly to his son: ‘As soon as you have buried my body, mobilise the Zulu nation and attack Zibhebhu and fight against him. You will defeat him, for I will be in the midst of my army.’

On 5 June 1884, the sun low in the sky, Dinuzulu led his men into battle against Zibhebhu. With his 10,000 warriors were a hundred armed Boers, white descendants of German and Dutch settlers, who were eager to extend the Transvaal, their territory bordering northwest Zululand. Two weeks earlier they had crowned Dinuzulu King of the Zulus. The young man had sat enthroned on an empty beer crate and in lieu of holy chrism was anointed with castor oil. (Anyone acquainted with Christian ritual would have recognised the ceremony for what it was, a mockery.) It was agreed they would give him military support, in exchange – here his youth showed, disastrously – for as much land as their leaders ‘may consider necessary’.

Dinuzulu’s army and the Boers pursued Zibhebhu for four days, in drought, along the sluggish brown Mkuze river. Two hills came into view, half a kilometre apart and 200 metres high: one was domed, the other craggy, their flanks thick with thorn bush. To the east, these twin peaks: Gaza and Tshaneni (‘Ghost Mountain’ to the British); to the north the rivers Mkuze and Phongolo. A gunshot broke the silence. The Mandlakazi were forced to pre-empt their attack. The uSuthu were driven back, only for the Mandlakazi to be driven back in turn by the Boer rifles. In an hour it was over, just the smell of cordite and of opened bodies on the wind. Hundreds of Mandlakazi were killed, including six of Zibhebhu’s brothers. The survivors fled, abandoning 60,000 cattle, which were shared between Dinuzulu’s warriors and the Boers to whom they owed their victory.

In exchange for their support, the Boers would eventually claim some 5,000 square miles of Zululand’s most fertile farmland, including the sacred eMakhosini Valley. The kingdom’s death knell had sounded, even if Dinuzulu could not allow himself to hear it.

Such a flagrant attack on Britain’s ‘faithful ally’ would not go unanswered. Six hundred Royal Dragoons were sent to support Zibhebhu. His uncles at his side, Dinuzulu withdrew with 2,000 men to the limestone caves of another mountain, Ceza, twenty miles north of oNdini. With Ndabuko and Shingana he watched as the British advanced, day by day, across the plains, leaving burning homesteads in their wake. He was twenty, his father four years dead, and well aware he faced imprisonment or exile, if not death.

On 7 August the British heard singing coming from Mount Ceza: the men were chanting an uSuthu war song as they torched their huts before retreating across the nearby Sikhwebezi river. Dinuzulu and Ndabuko with their bodyguard went north. Evading the British, they crossed a country in flames. For the first time, Dinuzulu was wearing across his chest the iziqu, the strings of willow-wood beads worn by one who has honoured himself in battle.

By night, in disguise, Dinuzulu made his way by train to Pietermaritzburg, where there lived a woman he trusted. ‘I was born among Zulus,’ wrote Harriette Colenso, ‘and I call myself Zulu.’ She was her father’s daughter as Dinuzulu was his father’s son. She would come to care for him like a younger brother. Born in 1847 in Norfolk, England, she had moved to Africa at the age of seven. Her father, Cetshwayo’s friend John Colenso, Bishop of Natal, had died in 1883; if the Natal colonists expected Harriette to be any more accommodating than the old man, that expectation did not survive a meeting with her. Among Zulus her name was Udhlewdhlwe, ‘walking stick’ – she who had supported her father’s every step. It would be her lifelong objective to preserve the union of Zululand under the uSuthu royal family. Following Dinuzulu’s flight from Mount Ceza, she sent a message urging him and his uncles to surrender: ‘Just as your dying in a heap will cover up and make things smooth for those who have slandered you, the other road, that of putting yourself in bondage that the case may be tried, will enable us to expose the treachery by which you are hemmed in.’

Three and a half months later, on 15 November, an unknown man with twenty followers appeared at Bishopstowe, the Colensos’ mission station and home near Pietermaritzburg. Harriette was away in Eshowe. Her sister Agnes wondered if the man before her was indeed Dinuzulu. But who else could he be? ‘The knowledge of the will and power of his enemies made my heart ache,’ she remembered, ‘because he still had faith in that far off, and for the Zulus apparently unobtainable, justice of England.’ Leaving Dinuzulu with her mother, she rode into Pietermaritzburg to cable Harriette.

The Court of Special Commissioners in Eshowe sat between November 1888 and the following April. Under consideration were the cases of seventeen men, foremost among them Dinuzulu and his uncles Ndabuko and Shingana, who had surrendered separately from the young king. Colenso had retained the services of the most respected lawyer in British Africa, Harry Escombe, whose fees nearly ruined her. (It was not the last time she exhausted her finances on Dinuzulu’s legal defence.) Ndabuko’s case opened on 15 November. The charges: disobedience, defiance, contumely, violence against Her Majesty’s subjects and forces; stealing ‘certain Horned Cattle’; involvement in the murder and mutilation of a tradesman named Klaas Louw. Ndabuko, who was rarely moved to anger: ‘I have nothing to say to all these lies.’ He insisted, furthermore, that his nephew ‘should not be brought into this matter; he is still a child’. Dinuzulu himself, meanwhile, was charged with rebellion, public violence and murder, and Shingana with murder and ‘disobedience’.

On 27 February 1889 the sentences were announced: all three were found guilty, as British subjects, of high treason. Shingana was sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment; Ndabuko to fifteen. ‘Dinuzulu,’ announced the judge: ‘after a patient hearing of your case we are justified in saying to you that we are convinced . . . that your intention was to overthrow the existing form of government in Zululand. You are sentenced by this court to imprisonment for ten years.’

But Osborn, the resident commissioner, maintaining that their continued presence in Zululand ‘would be sufficient to keep alive a smouldering current of active disloyalty’, recommended they be ‘removed to some safe place across the sea’ – somewhere far from the influence of Miss Colenso. The British Secretary of State agreed. ‘In a more isolated British possession, they may, subject to good behaviour, be allowed a large degree of freedom.’ On 19 January 1890 the three were led from their cells and presented to the Governor of Zululand, Sir Charles Mitchell.

Grave but polite, he addressed them as if they were headstrong children:

The Queen with Her Indunas [that is, advisers] have read over all the evidence and her wise men of the Law and Chief men have advised Her that the sentences passed are the right ones. But the Queen said, ‘These men have been chiefs of their land and it would not please me, that they should work as common prisoners. Therefore I wilt send them to a country in my dominions, where they can enjoy indulgences which it is impossible to grant them in Zululand, where they would be shut up in a cell and not be able to see the grass.’

‘What will become of the people remaining here?’ Dinuzulu demanded. ‘I mean the women, my family?’

‘Do you think anybody will molest them?’

‘It is a trouble to my people at home, not seeing me.’

‘It is a trouble to my people at home, not seeing me.’

But as Dinuzulu observed, the governor was free to go back to England whenever he wished.

For the British in Zululand, as for the French and the Russians in their respective territories, exile was in part a practical measure, as we have seen – to decontaminate the metropole, to suppress any ‘current of active disloyalty’; but it’s also the case that to dictate your enemy’s whereabouts on the planet, as if they were a chess piece, as if they were dust, is to flaunt a frightening and demoralising imperial supremacy.

Mitchell had been instructed to impress on the three men that their sentence constituted a ‘most material mitigation’ of their punishment. Seventy-five years earlier his compatriots had said something similar to another defeated enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte – ‘its local position will allow of his being treated with more indulgence than could be admitted in any other spot’ – before shipping him to the same remote island in the South Atlantic ■

Exiles: Three Island Journeys

Faber & Faber, 5 May 2022

RRP: £19.00 | 320 pages | ISBN: 978-0571352982

A luminous exploration of exile - the people who have experienced it, and the places they inhabit - from the award-winning travel writer and author of The Immeasurable World and The Moor.

This is the story of three unheralded nineteenth-century dissidents, whose lives were profoundly shaped by the winds of empire, nationalism and autocracy that continue to blow strongly today: Louise Michel, a leader of the radical socialist government known as the Paris Commune; Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, an enemy of British colonialism in Zululand; and Lev Shternberg, a militant campaigner against Russian tsarism.

In Exiles, William Atkins travels to their islands of banishment - Michel's New Caledonia in the South Pacific, Dinuzulu's St Helena in the South Atlantic, and Shternberg's Sakhalin off the Siberian coast - in a bid to understand how exile shaped them and the people among whom they were exiled. In doing so he illuminates the solidarities that emerged between the exiled subject, on the one hand, and the colonised subject, on the other. Rendering these figures and the places they were forced to occupy in shimmering detail, Atkins reveals deeply human truths about displacement, colonialism and what it means to have and to lose a home.

Occupying the fertile zone where history, biography and travel writing meet, Exiles is a masterpiece of imaginative empathy.

"Atkins spins a marvellous tapestry of colourful tales, beautifully weaving history and travel accounts." – Andrea Wulf

"Gracefully written . . . Brilliant." – The Economist

"Rarely has a book been more timely." – History Today

William recommends:

⇲ Magema Fuze: The Making of a Kholwa Intellectual by Hlonipha Mokoena (University Of KwaZulu-Natal Press, January 3, 2011)

⇲ The View Across the River: Harriette Colenso and the Zulu Struggle Against Imperialism by Jeff Guy (University of Virginia Press; Illustrated edition, January 29, 2002)

⇲ Paulina Dlamini: Servant of Two Kings by Henrich Filter and S. Bourquin (University Of KwaZulu-Natal Press, June 19, 1986)

⇲ Zulu Thought-Patterns and Symbolism by Axel-Ivar Berglund (Indiana University Press, October 1, 1989)

The Black People and Whence They Came by Magema Fuze, translated by Harry Lugg (University Of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 1979)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Kate Burton at Faber. The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Hlonipha Mokoena of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.