Excerpt: Fabric by Victoria Finlay

Victoria Finlay spins us around the globe, weaving stories of our own relationship with cloth

In Fabric: The Hidden History of the Material World, bestselling author Victoria Finlay spins us around the globe, weaving stories of our own relationship with cloth and asking how and why people through the ages have made it, worn it, invented it and made symbols out of it. And sometimes why they have fought for it.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Victoria Finlay

When I was writing ⇲ Fabric, I found myself pushing back the planning of the silk chapter until almost the end. With barkcloth and sackcloth and linen and cotton and the others, there were clear and burning questions in my mind that I was excited to find the answers to. With silk, I was initially less interested in it because it was so obviously luxurious, and having lived in Asia for more than a decade, I had a vague (and as it turned out totally unfounded) feeling that I probably already knew much of what I needed to know.

But then I went to Lyon, historical centre of France’s silk industry, and I met a silk moth for the first time. It looked like a fluffy white rabbit and like the white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, it was the moth itself that would be my guide into the rabbit hole of research into, and discovery of, the extraordinary fabric that is silk. In the end it was a journey full of unexpected turns and discoveries. And it was a journey that began where it needed to begin, with a sharp sense of compassion for all the creatures that die to give us silk.

Fabric is the third in what’s turned out to be a trilogy of books about the histories of small, bright and (usually) lovely materials. And when I was researching each of the books I found doors opening into worlds of history and struggle and beauty and symbolism, and every time it was a surprise.

– Victoria Finlay

Silk

An excerpt from Fabric: The Hidden History of the Material World

I look at the moths on the table. They're balancing on wooden rods sticking up from what looks like a cribbage board. One has its wings spread and the other has them upright. And they're adorable. That's not a technical term, but the wings are huge and fluffy, like white rabbit ears or toy donkey ears, and their antennae are like oversized lashes fringed with dark threads. Their forelegs are strong and furry: teddy bear legs. Their eyes are black buttons, and their plump bodies are covered with soft hair. It’s as if a puppy has somehow got muddled in the evolutionary mix with a fat white hummingbird.

I hadn't expected to love the silk moth so much.

Below is a broken cocoon from which one of them has merged. It's the size of a robin’s egg and yellow as a lemon. All around is a delicate mesh of fibre catching the sunlight.

'Can I touch?' I ask.

It feels soft. When I close my eyes I'm not even sure my fingers are making contact with anything. I think of how the fineness of a silk filament was once the mark against which all textiles were measured. In France the measurement was named a denier, after the smallest possible coin, one twelfth of a sou. Seven-denier tights, the sheerest you can buy today, are about the thickness of seven strands of silk [1].

How Lyon became a Silk Town

Medieval and Renaissance court fashion in Europe demanded silk. Virtually all medieval courtly dress from the early twelfth century onwards was inspired by what crusaders had seen on their travels and by what they had brought back. And many of the loose, brilliantly coloured clothes being worn by rich people in the Middle East in the twelfth and thirteen centuries were made of silk.

After the First Crusade in around 1100, Queen Matilda, wife of Henry I of England, led a fashion for women plaiting their hair and wrapping it in silk casings. Some of these silk-wrapped plaits were so long that they (or the secret hair extensions hidden within them) reached right down to the floor, flicking as they passed, attracting the eyes of onlookers.

.jpg?auto=webp)

New too were surcotes: coats and long jackets worn over other clothes. These were copied from loose Middle Eastern clothing and were originally worn by European soldiers over their armour to protect the chain mail from rusting. It was also a way of looking bulkier and more powerful as you charged into battle with red crosses on white fabric flowing behind. When surcotes arrived in Europe, women adopted them too. The many variations included the cyclas, a sheer silk robe with a side slit, worn over your dress. It was often fashionably cut a few centimetres too short, so as you walked you could lift it and provide a tantalising glimpse of the finer fabric below.

By the early sixteenth century, the post-crusader fashion for wrapping and revealing had morphed into richly brocaded sleeves and tunics that were slashed to show the quality of the fabric below them. Like deliberately torn designer jeans today, they gave an air of being both nonchalant and sexy, and both men and women enjoyed the effect.

In 1514, Lucas Cranach painted Renaissance Europe's first full-length portraits. They showed both Henry the Pious, Duke of Saxony, and his wife Catherine of Mecklenburg wearing slashed sleeves. (In fact Henry has so much gold lining showing through the profusion of holes in his tunic, coat and breeches that the subtlety is entirely lost.)

A generation later, in 1538, Holbein the Younger would paint a famous portrait of King Henry VIlI wearing a tunic with diamond-shaped cuts across his chest, with flecks of white silk pushing through each of them, as if they were handkerchiefs trying to escape.

Across the Channel, Francis I of France – three years younger than Henry VIII and one of his great rivals – wanted to be a thoroughly modern fashionable man in a thoroughly modern fashionable country. However, all those imported ruffs and slashed sleeves and good brocades were bankrupting the Treasury. France was also at war with Italy, which was still Europe's main source of silk.

He needed a plan. Lyon was his second capital. It lies on the confluence of two rivers, the Rhône and the Saône, giving excellent connections.

It was close enough to Piedmont to get there overland in just over a week, whenever war allowed it, and, as a city with royal permission to hold four fairs a year, it was already a centre of the textile trade. There were many weavers living there and the city seemed to present an opportunity for setting up a viable French silk industry.

Also, the climate was not unlike that of Piedmont, which made the king think that perhaps, once they'd figured out how to do it, they might be able to grow mulberries and let silkworms thrive. Francis's distant cousin and predecessor, Louis XI, had had tried to do something similar in 1466, by giving privileged status to Lyon weavers, but had failed. Francis was going to do it differently – through tax concessions.

In the early 1530s, two Piedmont master weavers agreed to move to Lyon and weave fabrics of 'gold, silver and silk' in exchange for the promise that they wouldn't have to pay ordinary taxes. In 1536 Francis signed a letter patent confirming this and soon Lyon became France's centre of luxury silk, attracting weavers from Genoa and Avignon as well as from Piedmont. Later, the region became the heart of French sericulture as well.

The English tried to get involved. They didn't actually have any of the things they needed to start their own silk business. They didn't have the eggs. They didn't have the mulberries. They didn't have the skilful people. But they did have the desire to get in on the act. At the time, English merchants would buy counterfeit silks in northern Europe, put the equivalent of 'Made in Venice' labels on them, and sell them around the Mediterranean at a mark-up, to people who either didn't know better or liked to feel they had had a bargain.

In the early seventeenth century, the Scottish-English king, James VI and I, wanted to start a domestic silk industry, so he had a four-acre mulberry garden planted in what is today the grounds of Buckingham Palace. The gardeners were called the King's Mulberry Men. In 1607 it was announced that owners of large estates were expected to buy and plant ten thousand mulberries each; more modest householders understood that it was their patriotic duty to plant at least one. Charlton House, one of the few surviving Jacobean mansions in London, has a mulberry in its garden that is supposedly from one of those first plantings. But the king was wrongly advised. Most of the trees sent from France were black mulberries, not white. They bear nice berries. But silkworms don't like the leaves.

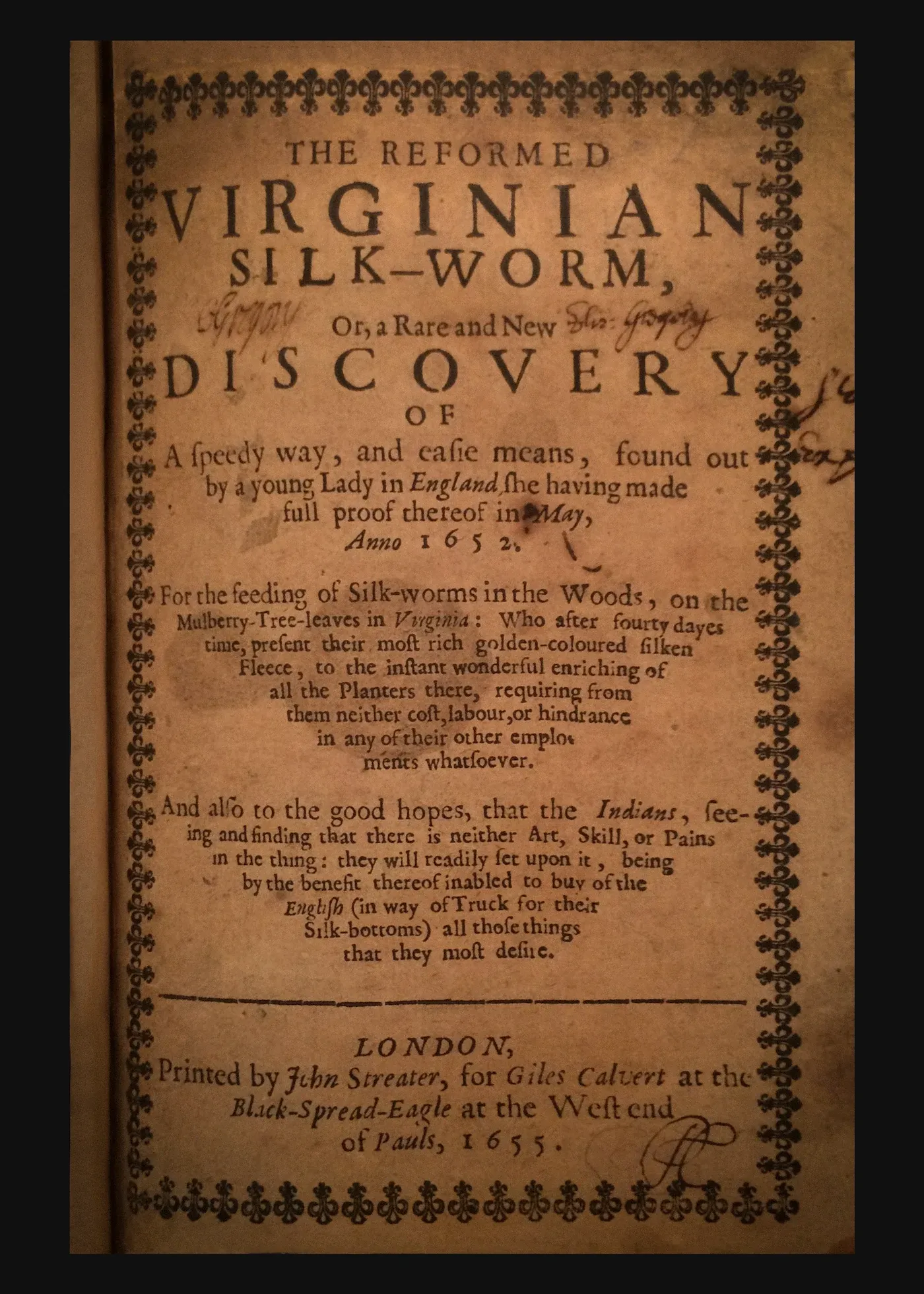

A few of the right mulberry trees did make it to England in the first part of that century, however, and in 1655, a printer near the Black Spread Eagle public house near St Paul's Cathedral published a tract about cultivating silk from them. It was titled The reformed Virginian silk-worm, being intended to encourage the industry in America. It became a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic, with its claims to include a 'rare and new discovery of a speedy way and easie means' for raising silkworms, particularly in the colony of Virginia. It stated that the method had been discovered by 'a young Lady in England, she having made full proof thereof in May, anno 1652'.

The anonymous scientist turned out to be Virginia Ferrar, born twenty-four years earlier. Ferrar grew up with her parents and younger sister as well as her aunt, uncle and ten younger cousins in a small religious community in the countryside outside Cambridge.

It was called Little Gidding, and the twentieth-century American poet T. S. Eliot would later make it famous by writing one of his Four Quartets based on a visit there. Ferrar had been named after the newly established colony in America of which her father had once been deputy governor, and as the English Civil War raged throughout the country from 1642 onwards, she raised silkworms in the community's quiet garden and kept assiduous notes.

She learned that worms enjoyed lettuce, but that they didn't convert it into good silk, and that the best time to sow white mulberry seeds in windy Cambridgeshire is April, in 'ground that is well dunged, and placed so that the heat of the Sun may cherish it, and the nipping blasts of either the North wind or the East may not annoy it'. And the best way to care for the silkworms, she found, was to 'lay them in a piece of Say [a woollen fabric] and carry them around with you close to your body, in a little safe box, and at night lay them in your bed or between warm pillows'.

She (or possibly her father) made notes and drawings in the family atlas. The writing is in the margins; the drawings (including one of a pupa wrapped in its cocoon like a corpse) are in spaces between sections of printed text, all of which suggest that they needed to be secretive. Much of the research was done when England was at the height of its brief Commonwealth: King Charles I (the son of James I) had visited Little Gidding several times, had been executed a year after his last visit; Christmas and theatre were banned; and luxuries were frowned on. And although silk was not forbidden – the wealthier Puritans sometimes wore it in modest colours beneath their dark clothes – it wasn't much favoured either.

So why did she risk it? The answer probably comes from her faith, as well as her sense of having a connection with America through her name. Ferrar had always been keen that the silk industry should be taken up in the state she was named after, which was thought to have a similar climate to China's.

She believed that tobacco (then as now one of the top export crops in Virginia) was bad, just 'smoak and vapour', while silk is a 'reall-royall solid rich-staple Commodity'.

She wanted, by working with the thread that comes from transformation, to help change the industry of a new colony, and enable people to make something to embody the beauty of the world rather than something to encourage addiction, or, as she described it in 1652, 'the pernicious blinding smoak of Tobacco, that thus hath dimmed and obscured your better intellectuals'.

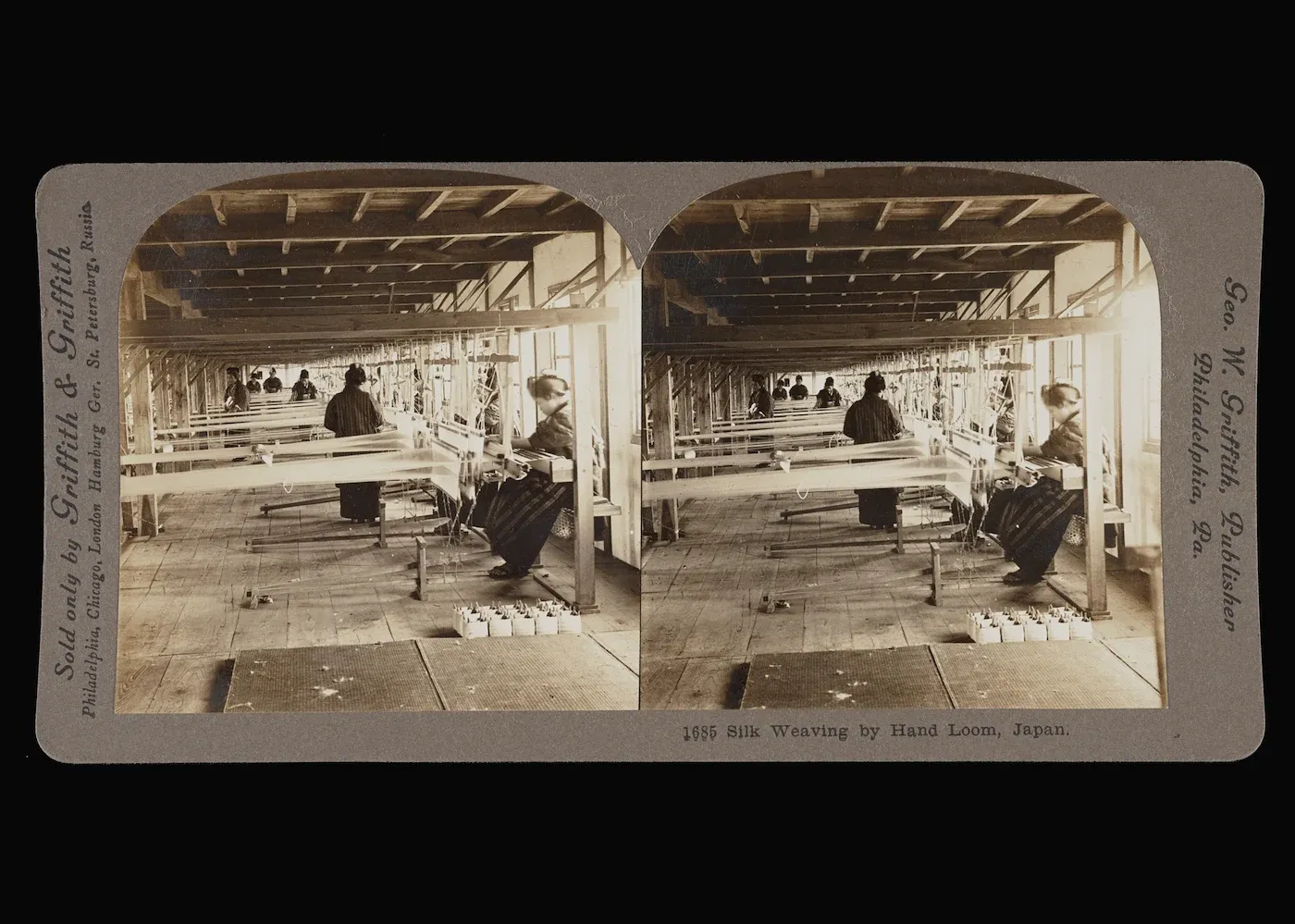

Japanese Silk Man in New York

In 1876, twenty-year-old Arai Rioichiro arrived in New York. He came from a wealthy landowning family in the mountains of Kozuke, a hundred kilometres north of Tokyo. The region was then the heart of Japanese sericulture: almost every peasant family was involved in raising silkworms. It was hard work for the women. To get two kilograms of silk in a year, they had to spend the spring and summer constantly feeding about seven thousand worms with some two hundred kilograms of mulberry leaves, which they were also responsible for picking. 'No one who has heard the sound will ever forget the low, all night roar created by the munching of thousands of voracious silkworms in a Japanese mountain farmhouse', wrote Arai's granddaughter Haru Matsukata Reischauer, from whose family memoir I've taken this account.

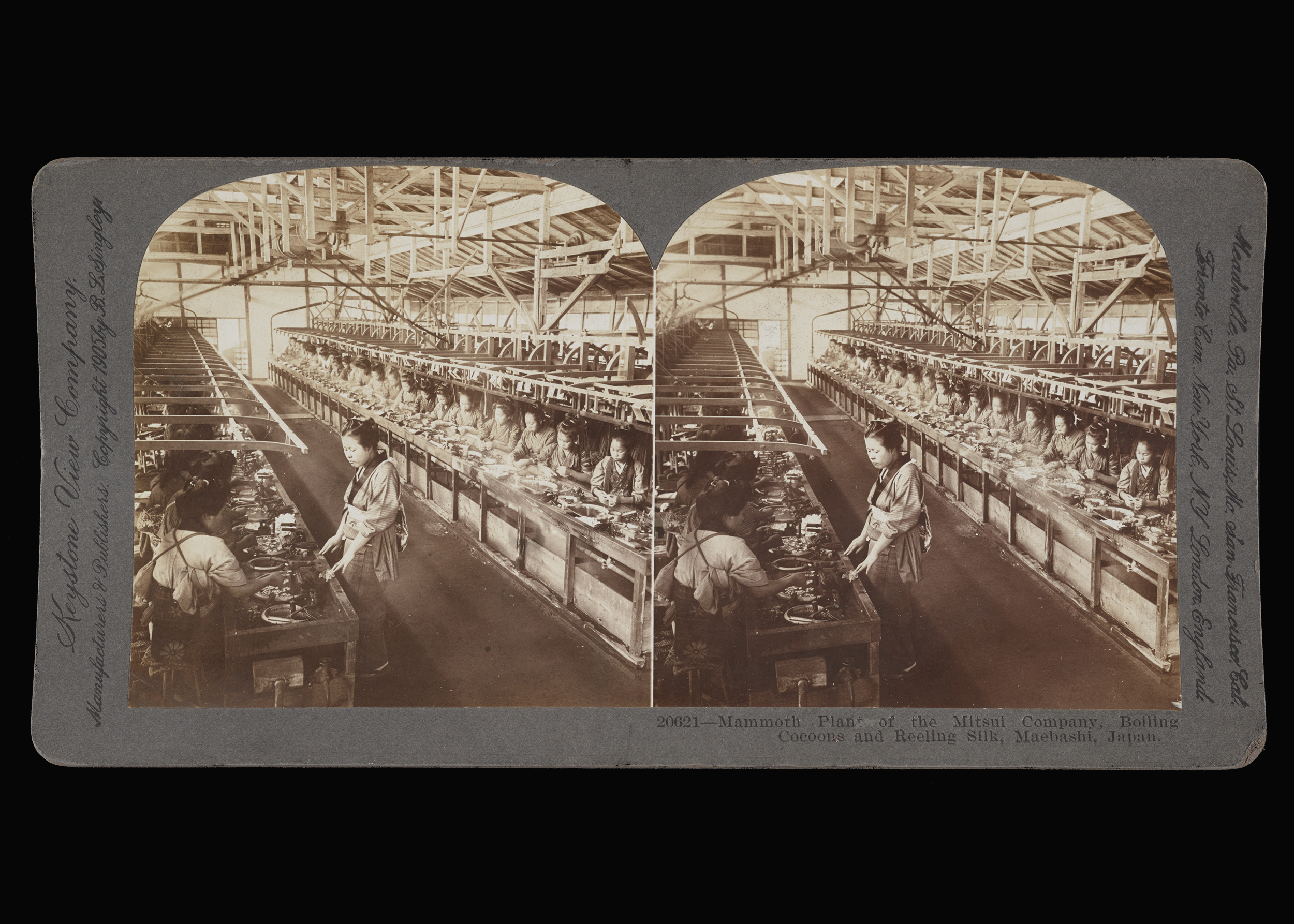

While Arai had been busy learning English after the Meiji Restoration (which happened when he was fourteen years old) his older brother Chotaro had been apprenticed in the silk trade. Silk had been reeled by hand for centuries, but that was about to change. By spring 1875, Chotaro had built his own Western-style mill, using a no-interest government subsidy of three thousand yen. He installed some machines for reeling the silk from the cocoons (rather than doing it by hand), and other machines for throwing it – combining filament strands and twisting them together, ready for the loom.

Working with the local farmers and making their raw silk into yarn was all fairly straightforward. The hard thing, he was about to discover, was selling it at a profit.

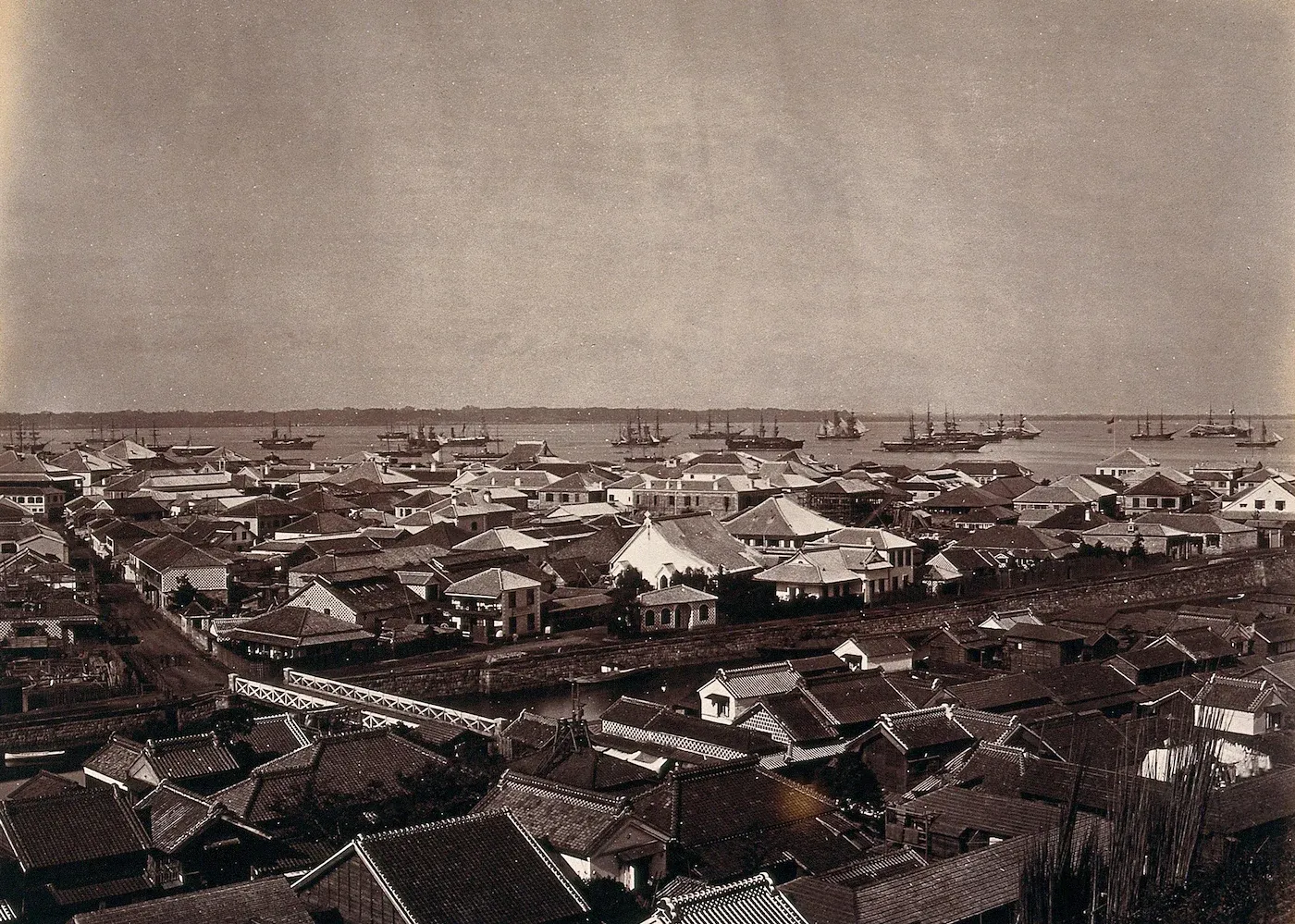

First, he tried consigning the threads to a ninushi, the local merchant who dealt directly with foreign traders in Yokohama, Tokyo's closest port. He was horrified to realise that he'd sold at a loss. He transported the next year's shipment the hundred or so kilometres to Yokohama himself, avoiding the ninushi's high commission, but once he'd paid the tax and the shipping to London he made almost nothing. Most foreigners wouldn't deal with him or other producers directly; they preferred to use Chinese middlemen, along the lines of the old comprador system that had worked in Macau, Hong Kong and China for years [2].

It was impossible at first to find out what silk prices were overseas and so know what price they could demand. It was only when one silk merchant found a copy of The Times that they realised how high the price of silk was in London and understood that the only way to succeed in this new international world was to go to the end buyers themselves.

Now in March 1876, Chotaro's brother Arai was one of six young Japanese men walking up the gangplank of the SS Oceanic heading from Yokohama to San Francisco. He carried a carpetbag of samples as well as a purse full of Mexican silver dollars – the international currency of East Asia – and three spare Western style suits, a new thing for Arai who until then had only worn kimono. His two hundred and seventy yen had paid for a hammock in a berth with no windows, where he had to sprinkle red pepper at least once a day to get rid of the stench.

In New York he learned that Japanese silk had a bad reputation. The few bales that had arrived via Europe over the previous few years had been poor quality, with bits of metal stuffed into them to increase the weight. Nevertheless, after a few weeks he secured his first order, from a silk merchant on Mercer Street called Richardson: just four bales, weighing a hundred pounds each, at $650 a bale, with delivery by September and 10 per cent off for early payment.

It would be the first time Japanese merchants had exported silk directly to North America, and the first time any Japanese silk had arrived in North America via the Pacific, and not via Europe. It was a coup.

Shortly after he and the buyer shook hands, the price of silk shot up. After another outbreak of pébrine [3], Italy and France had ordered an emergency ten thousand bales from Japan, with the price almost doubling overnight. In a series of letters – each taking several weeks to arrive as the trans-Pacific cable was still two years away – Chotaro begged his brother to raise his price: it was going to take everything the family owned to fulfil the deal. Arai refused; he'd made an agreement.

And he was right: although the brothers lost two thousand dollars on that first transaction it paid off. From then on, they, and Japanese silk, were trusted [4]: by 1929, from the original four bales in 1876, more than five hundred and thirty thousand bales of silk would be imported from Japan – many arriving on special 'silk trains' speeding across Canada or the United States in under eighty hours coast to coast to beat down the extremely high transport insurance rates.

In 1880, however, four years after that first order, and on his first visit home, Arai had his first understanding of how quickly things were changing in his native land. Dressed in the latest New York fashions – complete with gold chain and fob watch – he was astonished to realise that nobody looked at him at all. All his male friends were also wearing Western clothes, and in fact it was Arai who was the one to keep remarking at how things had changed. No samurai swords on the streets, the shops full of Western goods. And how expensive everything was.

That year was also the first time the sound of a power loom could be heard in Nishijin, the traditional silk-weaving district in Kyoto. Jacquard attachments had arrived seven years earlier, brought back by two Japanese weavers who had made the journey to Lyon to learn how to use them, and by 1880 many more weavers were using them than ever before.

It was raw silk that helped Japan control its runaway inflation in 1881, and it was raw silk that helped it build up a trade surplus of twenty-eight million yen four years later. It was raw silk that paid for all the rapid military upgrades, which meant that when Japan went to war with the stuttering Qing Dynasty in China over influence in Korea in I894, Japan won; and when, in 1904, Japan and Russia went to war over Manchuria and Korea, Japan won again.

Silk kept delivering. Even during a depression in America in 1907, the demand for Japanese silk scarcely faltered. People turned away from the expensive Italian silks, but they still wanted the cheaper Japanese ones.

It was in large part due to the sudden increase in wealth caused by the silk trade that Japan had the financial wherewithal and links to the West that enabled it to rapidly industrialise and militarise. This contributed to the Japanese expansionist movement extending beyond Korea into China and then throughout South East Asia and the Pacific. It helped Japan become the military powerhouse it was in the 1930s when it invaded China, and later in the 1940s when it invaded much of South and East Asia. If it hadn't been for the massive flow of capital and technical knowledge that had flowed into the country because of Europe's silk famine, industrialisation would have been slower to arrive. And the pattern of the world would have shifted in different ways ■

1. The metric equivalent is the tex, short for 'textile', the weight in grams of a kilometre of any yarn: 'ten-denier' stockings are approximately 1.1 tex.

2. Comprador: from the Portuguese for buyer; used in Macau from the sixteenth century.

3. A parasitic disease affecting silkworms, named pébrine 'pepper' after the characteristic black spots that appear on their bodies. Affected worms ate little and grew slowly, and if they survived long enough to make a cocoon the silk was sickly, brittle and unreliable.

4. Arai would be the first Asian elected to the board of the Silk Association of America and his company would handle nearly a third of all silk exports.

Fabric: The Hidden History of the Material World

Profile Books Ltd, 11 November 2021

RRP: £25.00 | ISBN: 978-1781257067

How is a handmade fabric helping save an ancient forest? Why is a famous fabric pattern from India best known by the name of a Scottish town? How is a Chinese dragon robe a diagram of the whole universe? What is the difference between how the Greek Fates and the Viking Norns used threads to tell our destiny?

In Fabric, bestselling author Victoria Finlay spins us round the globe, weaving stories of our relationship with cloth and asking how and why people through the ages have made it, worn it, invented it and made symbols out of it. And sometimes why they have fought for it.

She beats the inner bark of trees into cloth in Papua New Guinea, fails to handspin cotton in Guatemala, visits tweed weavers at their homes in Harris, and has lessons in patchwork-making in Gee's Bend, Alabama - where in the 1930s, deprived of almost everything they owned, a community of women turned quilting into an art form.

She began her research just after the deaths of both her parents - and entwined in the threads she found her personal story too. The book became her journey through grief and recovery. It is her own patchwork.

"Subtle, compendious and rich ... an emotive and serious work of what you might call history on the distaff side." – James McConnachie, The Sunday Times

"Dazzling ... Finlay's adventures, vividly recounted, make enthralling reading ... This book is equally an inspiration and an education." – Bel Mooney, Daily Mail

"I am wildly impressed by the depth of her research and the stories she finds." – Alexandra Shulman, author of Clothes... And Other Things That Matter

Victoria: Some of the many illustrated books on fabrics that have had me entranced include:

⇲ Patchwork: A Life amongst Clothes by Claire Wilcox (Bloomsbury Publishing; 1st edition, 2020)

⇲ The Quilts of Gee’s Bend by William Arnett and Paul Arnett (Tinwood Books, 2002)

⇲ Anni Albers by Ann Coxon, Briony Fer and Maria Müller-Schareck (Tate Publishing; 1st edition, 2018)

⇲ Sheila Hicks, Weaving as Metaphor by Nina Stritzler-Levine, Arthur C. Danto and Joan Simon (Yale University Press, 2018)

Russian Textiles: Printed Cloth for the Bazaars of Central Asia by Susan Meller (Abrams; 2nd edition, 2007)

and also any copy of ⇲ Selvedge Magazine.

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Simon Trewin and Anna-Marie Fitzgerald. Cover jacket image from the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Author photograph © Katia Marsh.