Excerpt: Great Hatred by Ronan McGreevy

The Assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP

On 22 June 1922, Sir Henry Wilson – the former head of the British army – was shot and killed by two veterans of the First World War turned IRA members in what was the most significant political murder to have taken place on British soil for more than a century. Wilson’s assassination triggered the Irish Civil War, which cast the darkest of shadows over the new Irish State.

Drawing upon newly released archival material and never-before-seen documentation, Great Hatred is a revelatory work that sheds light on a moment that changed the course of Irish and British history for ever.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories foreword by Ronan McGreevy

In a field near a lake in the middle of Ireland there stands three dog graves. The graves are three faded, rounded limestone headstones with a concrete base to ‘Barney, 1895–1901’, ‘A Faithful Companion; Pat, 1901, Always a Rifleman’ and ‘Scraps, 1897–1907, A Great Companion’. The graves are the only personal link that remains to the Wilson family who lived in this part of Ireland until the Irish War of Independence between 1919 and 1921 which set up what is now the Republic of Ireland. Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP grew up on this estate. He was shot dead on June 22nd 1922 on the steps of his home at Eaton Place in London.

His killers, Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan, were caught and hanged on August 10th for the crime. Six days later, Wilson’s family home at Currygrane, Co Longford, was burned to the ground in revenge for the execution of the two men. Wilson’s brother James, known as Jemmy, had already left Ireland because of the political troubles and never returned. The graves symbolise the mass exodus of many southern Unionists, who wished to remain part of the UK, and felt they could no longer live in new Irish state. Between 1911 and 1926 the Protestant population of the twenty-six counties declined by a third from just over 10 per cent of the population to 7 per cent and continued to decline for decades after that.

— Ronan McGreevy

'I am an Irishman'

An abridged excerpt from Great Hatred by Ronan McGreevy

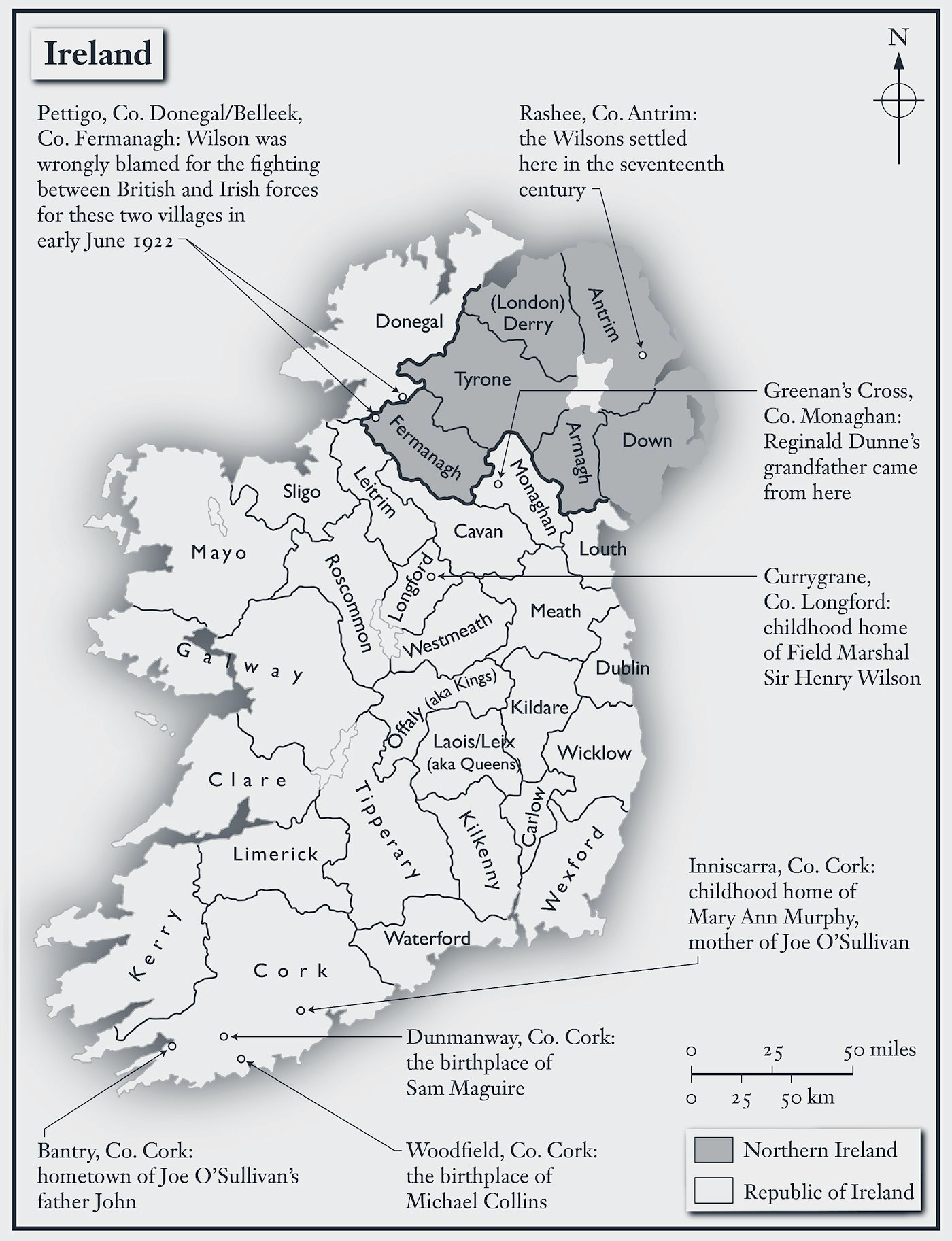

Two kilometres outside Ballinalee in north County Longford, about 115 kilometres north-west of Dublin, down a single-lane track lined by rhododendron bushes that bloom lilac and pink in the summertime lies the townland of Currygrane.

Its primary feature is Currygrane Lake, a lough of eighty acres in size, fringed by reeds and lined with stones, and lying beside woodlands of larch and birch trees. A slipway and a boathouse lead to a restored small stone cottage, once the herdsman’s, which is rented to anglers who come here for the coarse fishing, in particular for pike, bream, roach, perch and tench.

A kilometre away is a large, L-shaped, two-storey outbuilding next to a private house. It stands beside a large horse chestnut tree, of a kind which are plentiful on the estate. Its slate roof had fallen in and weeds grew from the crevices in the 200-year-old whitewashed rubble stone walls, but it has now been restored. This is all that remains of the Currygrane estate, where Henry Hughes Wilson was born and raised. Currygrane House, owned by the Wilsons, was built in the 1830s for a local landowner, William Lloyd Galbraith, a member of the Orange Order in the county. It was then bought by the Bond family, followed by the Wilsons in 1860.

Currygrane House sat on the crest of a hill, with a large lawn in front. No trace of the original house remains. In its place now are two houses owned by the Brady family, who have lived in the townland for seventy years. ‘The house of the planter is known by the trees,’ the poet Austin Clarke once observed, and Currygrane House was surrounded by mature horse chestnut trees, copper beeches and laurel bushes that remain from the Wilsons’ time. A solitary trace of Ireland’s British past remains on the perimeter wall of Noel Brady’s home. The post box retains the symbol of the Crown. When the Irish Free State came into being, the post boxes were simply painted over from red to green. Halfway between Currygrane House and the lake is a high ridge planted with trees and bushes called Bridget’s Hill or Miss Bridget’s Plantation, named after Henry Wilson’s niece Bridget, who was born in 1903.

The Wilsons did not consider themselves a rich family in comparison with many of their Anglo-Irish peers. In response to a proposal by the Land Commission in Ireland to reduce the rents of tenants in 1897, James Wilson Sr wrote to The Times:

1897

I had to deal with the excessive hardship which the present reductions of rent by the Land Commission is to bring down upon the smaller landlords. The general opinion I’m afraid is that Irish landlords are a comparatively rich class and that a man who has £10,000 a year can get on very comfortably even if his rent be reduced to £6,000 or £7,000 a year, though it may be he is treated unjustly. Alas! This is not true for although there are a few well-known rich Irish landlords, there are very many of small means on whom these reductions are falling not only unjustly but with cruel hardships.

Nevertheless, James Wilson added an annexe with a smoking room and billiard room to the original house. A pump system brought water from Currygrane Lake, and the house was one of the first places in Longford to get electric light, which was provided by a generator on site in the 1890s. The estate was inherited by James Wilson’s eldest son, James Mackey Wilson, known as Jemmy.

The 1911 census indicated a prosperous and thriving estate. There were thirteen stables, two coach houses, four cow houses, three calf houses, two dairies and a barn. It was good pastureland. Jemmy was both an antiquarian and a naturalist, and would often write to nature periodicals with the first sightings of swallows, cuckoos, corncrakes, chiffchaffs, spotted flycatchers and willow wrens. ‘After thirty years of careful observation of bird life here, never until today have I seen a Jay. I had him under observation with my opera glasses for at least a quarter of an hour and could not mistake his brilliant plumage,’ he observed in December 1918.

When the sun glimmers off the lily pads that fringe the lake and reflect the mature copper beech trees on the opposite side, it is hard to imagine a more tranquil place.

‘I am an Irishman, born in County Longford, and can say for about fifty years before Mr Birrell came into power in 1906, the front door of my home was never shut by day or night,’ Henry Wilson declared in a speech at Caxton Hall in London in May 1922. He was accused of anti-Irish bias, when to him it was about the difference between ‘right and wrong’ and England having to rule for the sake of the ‘99 out of 100 decent, quiet, peaceable folk in Ireland’.

Augustine Birrell was the Chief Secretary for Ireland from 1906 until the Easter Rising of 1916, after which he resigned. Birrell was a reforming and generally popular Chief Secretary whose brief it was to prepare Ireland for the modest measure of self-government, as envisaged in the home rule settlement. The Wilsons regarded home rule as an affront to the established order, where everybody knew their place. Wilson detested politicians, especially Liberal ones.

Outside Ballinalee is a memorial which remembers the Clonfin ambush during the War of Independence, when men from the North Longford flying column ambushed two lorry loads of Auxiliaries, killing four and injuring eight, on 2 February 1921. The IRA commander that day was Seán Mac Eoin, known as the Blacksmith of Ballinalee. Mac Eoin was Wilson’s neighbour.

Although their politics were at odds with those of most of their neighbours, the Wilsons were not unpopular landlords. Mac Eoin had himself threatened to burn Currygrane House to the ground during the War of Independence in 1921 if reprisals by Crown forces against local people did not stop. He told Jemmy to tell his brother to call it off. Jemmy protested that he had no such influence:

‘Well,’ I replied, ‘in that case it will be too bad for Currygrane and for you.’ I added that, should he attempt to leave, I would have him executed before he had reached Edgeworthstown or Longford.

The reprisals did stop. Jemmy reciprocated the gesture when Mac Eoin was sentenced to death by the British after being captured in March 1921, urging his brother to intervene and reprieve him. As it happened, Mac Eoin was saved by the Truce that ended the War of Independence in July 1921. Currygrane House was also saved, albeit temporarily. It was burned to the ground by the anti-Treaty IRA in an act of tribal spite in August 1922, less than two months after Henry Wilson was assassinated, the same faction that had been blamed, erroneously as it turned out, by the British government for the killing.

Mac Eoin had a grudging respect for Jemmy, who had ‘great courage’ and cleaved to his unionist convictions with sincerity. Writing in the 1960s in the Evening Herald, Mac Eoin recalled that Henry Wilson’s youngest brother Arthur set up a home industry with his wife Alice for girls in the district to earn money doing crochet and lace work. The Wilsons made no monetary gain from the enterprise, but their activities enabled ‘many girls, Catholic, Presbyterian and Protestant, to marry and save good dowries to settle them in life. They, the Wilsons, were a fine family and were popular in the country and in Ballinalee in particular.’ He regretted not being in a position to save Currygrane House from being destroyed by fire.

.jpeg)

Following on from Mac Eoin’s praise, an anonymous letter writer to the Evening Herald, who signed himself as ‘Longfordman’, was also complimentary of them. ‘The Wilson family were popular in County Longford. They were very good employers and contributed generously to all charities, irrespective of class or creed. Ireland is the poorer today through the loss of such families over great hatred the last forty years.’ That ‘Longfordman’ declined to reveal his real name indicates that such a viewpoint would not have been universally well received in Ireland.

There is no evidence, however, that the family was unpopular locally. They do not appear on the Land League’s list of rogue landlords who had exploited their tenants. In 1880 a ‘nefarious document’ was sent to James Wilson and universally condemned by his tenants, who praised him for having provided them with ‘handsome slated cottages and comforts they were heretofore unaccustomed to in the manner of living’. A certain sycophancy might be expected from his tenants, given his authority over them, but the parish priest Father Martin Monahan was moved to state that he ‘never heard an unkind word spoken of Mr Wilson’.

.jpeg)

Henry Wilson was born at Currygrane House on 5 May 1864. Daniel O’Connell once said of the Meath-born Duke of Wellington that ‘just because you are born in a stable does not make you a horse.’ O’Connell’s jibe was intended to suggest that the Duke was not Irish despite having been born in Ireland. Wilson, though, saw himself as Irish. Others did too, attributing his general garrulousness and vivaciousness to his nationality. Wilson was happy to play along with it when it suited him, but he never identified as an Irish nationalist. In the nineteenth century, being an Irish unionist was not regarded as a contradiction in terms.

He never identified with his birthplace nor with his neighbours. Unlike Jemmy, whose worldview was tempered by his engagement with local people, Henry Wilson had little to do with Longford in his adult life and formed the perception of an outsider about the people he grew up around. ‘I think we can safely say that the Persians are an absolutely rotten people, far more rotten than even the Poles or the South-country Irish and that puts them pretty low,’ he wrote in a letter to his good friend Sir Henry Rawlinson in June 1921.

When he stopped being a soldier in February 1922 and could speak freely, Wilson made clear his views that the Wilsons were an Ulster family, their roots in Longford were shallow and he had spent little time there. Instead, the Wilsons had spent ‘something like 250 years in County Antrim’, he declared in April of that year, after being elected as MP for the staunchly unionist North Down constituency. Wilson identified himself as a unionist, and just as importantly, was identified by Ulster unionists as one of their own. His identification with the cause of unionism and specifically with the creation of Northern Ireland in May 1921 made him a hate figure for republicans; although some were shocked by his death, few were outraged.

.jpeg)

As for the unionists, Northern Ireland’s first premier, Sir James Craig, declared on hearing the news: ‘Sir Henry Wilson has laid down his life for Ulster.’

Henry Wilson inherited a unionist sensibility that was impervious to rising nationalist expectations. Unionism, landlordism and the Protestant faith were the Holy Trinity of the Wilson family. His father, who died at the age of seventy-four in 1907, was a graduate of Trinity College Dublin, then a bastion of Anglicanism and imperialism in Ireland.

James Wilson was a member of the Irish Landowners Convention and served on its executive committee. The convention was a conglomerate of landlords who frequently opposed or sought to water down British government legislation redistributing the land of Ireland back to the nationalist majority. He was also a member of the General Synod of the Church of Ireland and held every position in the Church that a layman could hold.

He was also a member of the Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), an all-Ireland unionist party founded in 1891 to oppose plans for home rule, and the forerunner of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP).

Jemmy went further than his father and stood in the North Longford Westminster constituency as a unionist. In 1885, as an Irish Conservative, he achieved just 6 per cent of the vote in a two-horse race against the Irish Party candidate. Undeterred by this electoral chastening, he stood again in the general election of 1892, this time for the IUA, and won the same share of the vote. Such devotion to a cause that those around them had so emphatically rejected was a characteristic of the Wilson family that Henry shared. A lack of popular support for their ideals never deterred the Wilsons from pursuing their opposition to home rule for Ireland. Jemmy eventually took up the position of land agent in County Longford, his duties requiring a great deal of office work, drawing up agreements with tenants and receiving rents.

He wrote regularly to newspapers in Britain and Ireland about the issues of the day, usually to express his incredulity at the prospect of home rule and concessions by British politicians to that end. In 1901 he wrote a letter to The Times about the Irish land question and the attempt by the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Gerald Balfour, to bring forward legislation to resolve the issue once and for all. Jemmy wrote, a time-honoured refrain even from those Irish people well disposed towards the Union.

In 1908 he entered into an extraordinary public correspondence with Balfour’s successor but one, Walter Long, about the nature of home rule. Having heard of the formation of an ‘Imperial Home Rule Association’, Jemmy protested that the concepts of imperialism and home rule were ‘utterly incompatible – how imperialism and home rule could ever go hand in hand is beyond my comprehension’. By 1914 he had reached the conclusion that no compromise was possible in relation to home rule. It was either unionism or home rule, two mutually incompatible points of view that no amount of ‘conferences, congresses, conciliation, committees and all the rest’ could reconcile.

.jpg)

‘There are only two schools of thought in Ireland deserving any attention,’ he added in his letter to the Irish Times in June 1914, ‘those who desire to uphold the union intact and believe wholeheartedly in the beneficence of that splendid Act [the Act of Union] and those who really in their hearts, no matter what they say, are devoted to the idea of “Ireland as a nation”.’

Henry Wilson shared his brother’s disregard for the wishes of nationalist Ireland that never accepted and never would accept that the Act of Union was an act of beneficence. Jemmy was right, though, that there could be no compromise and partition would maroon Southern unionists in a nationalist state, as he wrote to The Times in 1914:

1914

I believe I can speak for the great majority of unionists in the three southern provinces when I say that they are entirely hostile to any move which the government may make to exclude the northern province. Unionists in the south and west have from the beginning of this great controversy great hatred of home rule in 1886, been definitely engaged in the one supreme object of maintaining the Union between Great Britain and Ireland intact and they cannot conceive at this crisis that any such policy as the exclusion of Ulster is feasible. It has not been easy for unionists in the south and west (in many places groaning under the intimidation exercised by their opponents) to give frequent and loud expression to their views, but, writing as an individual who knows something of the feeling in these districts, I can say that the last thing desired by at any rate the thinking section of the community is that this country should be dismembered in the way that rumour has it the government may propose to do.

The roots of the Wilson family’s uncompromising unionism stem from their origins among the English and Scottish settlers in Ireland in the seventeenth century. Henry Wilson was part of the seventh and last Wilson generation in Ireland. The original Irish Wilson was an Englishman, John Wilson, who is said to have arrived in the vanguard of King William III (‘King Billy’) in 1690, the most glorious year for the unionist tradition in Irelan. The date is as much symbolic as actual. The Wilson family’s desire to be associated with King Billy’s victory at the Battle of the Boyne is as important as the historic veracity of those claims ■

He is the presenter of the full-length First World War documentary United Ireland: How Nationalists and Unionists Fought Together in Flanders, which was shortlisted for best film at the Imperial War Museum’s short film competition in 2018.

Great Hatred: The Assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP

Faber & Faber, 26 May 2022

RRP: £20.00 | 464pages | ISBN: 978-0571372805

A gripping investigation into one of Irish history's greatest mysteries, Great Hatred reveals the true story behind one of the most significant political assassinations to ever have been committed on British soil.

On 22 June 1922, Sir Henry Wilson - the former head of the British army and one of those credited with winning the First World War - was shot and killed by two veterans of that war turned IRA members in what was the most significant political murder to have taken place on British soil for more than a century. His assassins were well-educated and pious men. One had lost a leg during the Battle of Passchendaele. Shocking British society to the core, the shooting caused consternation in the government and almost restarted the conflict between Britain and Ireland that had ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty just five months earlier. Wilson's assassination triggered the Irish Civil War, which cast the darkest of shadows over the new Irish State.

Who ordered the killing? Why did two English-born Irish nationalists kill an Irish-born British imperialist? What was Wilson's role in the Northern Ireland government and the violence which matched the intensity of the Troubles fifty years later? Why would Michael Collins, who risked his life to sign a peace treaty with Great Britain, want one of its most famous soldiers dead, and how did the Wilson assassination lead to Collins' tragic death in an ambush two months later?

Drawing upon newly released archival material and never-before-seen documentation, Great Hatred is a revelatory work that sheds light on a moment that changed the course of Irish and British history for ever.

"Intellgient and insightful." – Irish Independent

"Heart-stopping . . . The book is both forensic and a page-turner, and ultimately deeply tragic, for Ireland as much as for the murder victim." – Michael Portillo

"McGreevy provides more than the anatomy of a political murder; in reconstructing this era of blood, poverty and wartime trauma, he also gives full expression to the terrible forces that WB Yeats once called the "fanatic heart" and the "great hatred" – The Times

Ronan recommends:

The Lost Dictator: Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson by Bernard Ash (London, Cassell, 1968)

Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson: His Life and Diaries 2 vols by Sir Charles Callwell (London, Cassell, 1927)

⇲ The World Crisis by Winston Churchill (Penguin Books, 2007)

⇲ Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson: A Political Soldier by Keith Jeffrey (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Sophie Portas at Faber and Peter Moore.