Excerpt: His Majesty’s Airship by S.C Gwynne

The Life and Tragic Death of the World's Largest Flying Machine

From the moment the military officer, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, flew his airship over the waters of Lake Constance near Friedrichshafen in Germany in the summer of 1900, people saw these machines as new emblems of the modern world.

They offered an alternative to the aeroplanes that were being developed by inventors like the Wright Brothers in the United States. ‘Zeppelins’ or ‘the big rigids’ may not be as fast or as dexterous, people reasoned, but they were more graceful and better suited to the demands of long distance travel.

Or so the theory went. The early history of airships was, however, chequered with accidents. During the First World War, when they were deployed as offensive weapons by the Germans, many zeppelins fell to earth in terrifying hydrogen fireballs. Nor did the crashes end when the bullets stopped. In one horrifying incident in 1921 the airship R38, which belonged to the United States Navy, came down over the Humber Estuary in East Yorkshire. 44 out of the 49 crew were killed in the crash.

Despite the hazards, the major Western nations continued to develop airships throughout the 1920s. Just why they chose to do so is one of the questions the author S.C. Gwynne seeks to answer in his new book, His Majesty’s Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World’s Largest Flying Machine. Gwynne’s book is centred on the R101 airship disaster of 1930, but it also reaches back in time, as he seeks to evaluate the whole ‘Airship Era’.

In this excerpt for Unseen Histories, which is taken from His Majesty’s Airship, Gwynne considers why these ‘big rigids’ proved to be such a durable idea. One answer, he suggests, lies in the fragile condition of the British Empire in the 1920s.

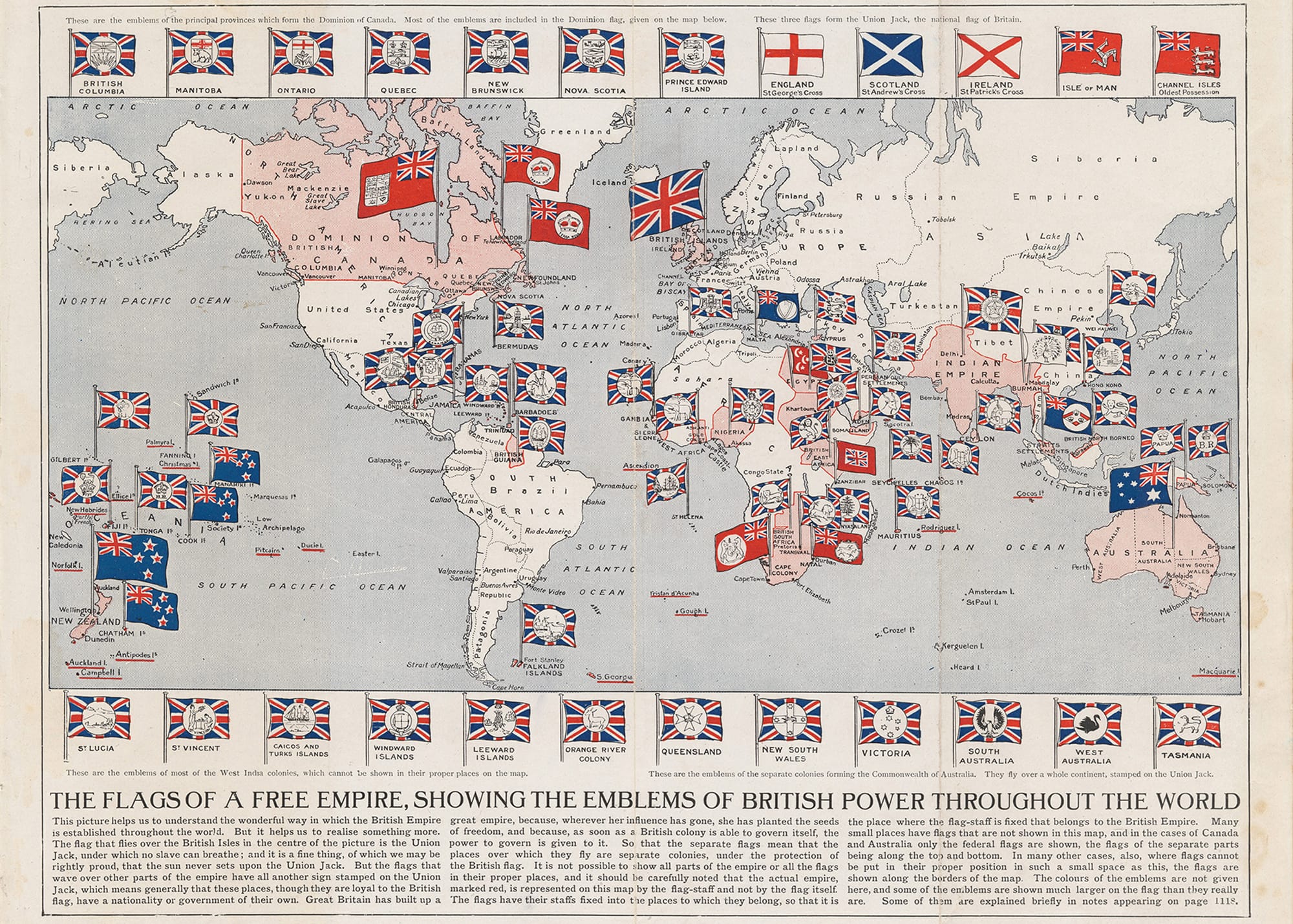

In spite of what appears in retrospect to be excruciatingly obvious—the lethal impracticality of the big rigids—the idea did not die, and airships did not disappear. By 1923 an idea for a new set of British airships—which would eventually include R101—would rapidly gain acceptance in the corridors of Whitehall. By 1924 a fully fledged plan was in place. Why, with so much evidence against it? For Great Britain the question could be answered with a single word: empire. After World War I the small island country held the largest imperial domain in human history, containing some 25 percent of the world’s landmass and 23 percent of its population—412 million people. Germany’s old colonies in the Pacific were now under the imperial hand. Britain had swallowed whole chunks of the vanquished Ottoman Empire, including Iraq, Transjordan, and Palestine. Persia was under its control. India, the colonial crown jewel, was now connected to Egypt and the Mediterranean by an unbroken chain of British-dominated sovereign lands, which in turn were part of a British-controlled strip of contiguous terrain that stretched all the way to the tip of South Africa. All this was added to the old self-governing British dominions: Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and South Africa. The sun, indeed, did not set on the British Empire.

But by the early 1920s it was showing persistent and uncharacteristic weakness. The main reason: its subjects were pursuing self-determination as never before. In South Africa the British had been forced to deploy half a million soldiers to suppress a ragtag guerrilla army of Afrikaans-speaking Boer farmers, which, at the end, numbered no more than twenty thousand. In British-ruled Ireland, the 1916 Easter uprising led to a war of independence and the founding of the Irish Free State in 1922. The world war had taken a gigantic toll. Many of Great Britain’s roughly 3 million casualties had been recruited from her colonies and dominions. Those countries, which had supplied 2.5 million soldiers to the war, wanted something in return for their blood. In India, a major supplier of troops, the 1919 Amritsar massacre of civilians by British troops was a signal event in that country’s swelling movement for self-rule. A 1920 rebellion in Iraq had to be brutally put down. The chinks in the imperial armour multiplied. Even on the high seas, where Britain had ruled for centuries, she was no longer the definitive naval power in the world. Her postwar strength was now determined by a “ratio” of sea power that governed the wartime Allies and locked Britain into parity with the United States.

Into this strange imperial half-world strode a new breed of imperialist, every bit as gung ho as their Victorian counterparts but without the old military punch. Like their predecessors, they believed that their empire was just, virtuous, benevolently paternalistic, and devoted to the advancement of civilization—though it was rarely any of these things and often their reverse. They saw an inevitability to the empire, a rightness that every football-playing Harrovian could immediately grasp. They believed, despite what was happening all around them, that history would remain resolutely Anglocentric. The notion that it would all come crashing down in blood and bitterness in a few decades would have been considered preposterous.

These forward-thinking men had been looking for ways to use the medium of the air to link the far-flung pieces of their domain—to reduce the time to cross it from oceangoing weeks to airborne days. They could thus change the nature of empire itself. They could improve it, bind it more tightly together, make it stronger.

Airplanes were considered, but there was no evidence yet that they would ever be practical for long distances: they were still slow, uncomfortable, and dangerous and required constant refueling. Even in the latter 1920s many aeronautical experts still believed that 110 miles per hour would be the commercial airplane’s maximum speed, its range no more than two thousand miles. (They were also very wrong about how much lift a fixed wing could provide.)

This allowed the airship crowd to assert that, by maintaining, say, 60 mph through twenty-four hours a day—thus, 1,440 miles— airships could cover far greater distances with more cargo and fewer stops than airplanes.

So British eyes came to rest on what appeared to be the perfect solution: rigid airships and their proven ability to cross great global distances. The empire had been built on violence and subjugation, but also, critically, on science, invention, and expertise, on being able to build what others could not.

Airships—technologically advanced versions such as R34 and L-59 that had flown thousands of miles without crashing—offered the chance to revive that old industrial dominance. Airships could reduce the time that the prime minister of Australia spent traveling to the Imperial Conference in England from a month to eleven days. India could be reached in five days, Canada in two and a half. These were tantalizing, world-shifting ideas. Communication was making quantum leaps in speed and distance. Travel would do the same.

The messy details of airship history were, as usual, conveniently overlooked ■

Excerpted from S.C. Gwynne's His Majesty's Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World's Largest Flying Machine

His Majesty's Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World's Largest Flying Machine

Oneworld Publications, 12 October, 2023

RRP: £25 | 320 pages | ISBN: 978-0861547081

In 1929, the R101 was the largest object ever to take to the air. It was meant to dazzle the world with cutting-edge technology and awesome size. Better than a plane, more luxurious than an ocean liner, the R101 would connect the furthest reaches of the British Empire, tying together far-flung dominions at a time when imperial bonds were fraying. It was, however, not to be.

The spectacular crash of the British airship R101 in 1930 changed the world of aviation forever. Most have heard of the fiery crash of the Hindenburg, a German ship that went down in New Jersey seven years later. But the story of R101 and its forty-eight victims has largely been forgotten.

His Majesty’s Airship recounts the epic narrative of the ill-fated airship and her eccentric champion, Christopher Thomson. S. C. Gwynne brings to life a lost world of aviators driven by ambition, and killed by hubris.

"I loved every page of this book. Even though we’re aware of R101’s tragic fate from the beginning, Gwynne still delivers an intensely dramatic story" – The Times

"Captivating... Gwynne spins a rich tale of technology, daring and folly that transcends its putative subject. Like any good popular history, it’s also a portrait of an age" – New York Times

"A Promethean tale of unlimited ambitions and technical limitations, airy dreams and explosive endings" – Wall Street Journal

Read more about the history of Airships:

Alexander Rose's ⇲ Empires of the Sky: Zeppelins, Airplanes, and Two Men's Epic Duel to Rule the World

Sir Peter G. Masefield's To Ride the Storm: Story of the Airship R101

Harold G Dick's The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships: Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg

Guillaume de de Syon's ⇲ Zeppelin!: Germany and the Airship, 1900–1939

Ernest A. Johnston's Airship Navigator: One Man's Part in the British Airship Tragedy 1916-1930

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Kate Appleton