Excerpt: Mummified by Angela Stienne

The stories behind Egyptian mummies in museums

Mummified explores the curious, unsettling and controversial cases of mummies held in French and British museums. From powdered mummies eaten as medicine to mummies unrolled in public, dissected for race studies and DNA-tested in modern laboratories, there is a lot more to these ancient remains than first meets the eye. From the apothecaries of the Middle Ages to the dissecting tables of the eighteenth century, and finally behind the screen of today's computers, Stienne revisits the stories of these bodies that have fascinated Europeans for so long.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Angela Stienne

The Egyptian mummy has been the subject of many books, and yet few have invited you – the visitor, the researcher, the curator or simply the inquisitive reader – to become an active museum visitor, and an agent of change. Very few have questioned why the Egyptian mummy is in museums around the world today. In this book, I share stories that attempt to counter the usual mummy narratives: they are stories of things that go wrong, stories of displacement, stories of practices that are a little odd, stories of studies that are outright racist, but also stories about individuals who were fascinated with mummies, stories about technology and its potential, and stories about where we go from here and what we can do next. In choosing which stories to tell, I have tried to cover a diversity of topics to help you think about this vast subject.

The stories take place in France and England, because that is where I have pursued my research but also where I have led workshops and engaged with the public. But it is not an entirely personal choice. France and England were also the two main countries to battle for the political, cultural and intellectual control of ancient and modern Egypt, and both countries have left these histories unchallenged for some time. I am going to invite you to question the bodies and artefacts that are inhabiting museums, and the narratives attached to them, wherever you are.

— Angela Stienne

The Mummy as Medicine, the Mummy in Medicine

An abridged excerpt from Mummified by Angela Stienne

On an ordinary road in West London, individuals from around the world are sharing a room. Their home is white, clinical. Africans, South Americans, Papua New Guineans, French, British in a single room. It is very quiet. This is a museum warehouse.

It is 2019, and the address is 23 Blythe Road, West Kensington. Originally built as the headquarters of the Post Office Savings Bank, this impressive building, known as Blythe House, is the store and archive of the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Museum and the Science Museum. In the portion of the building allocated to the Science Museum, in a small, characterless room, over a thousand bodies are living their afterlife together. A single room for the remains of people from all around the world. Two mummified bodies from ancient Egypt; heads from Africa; the artificially preserved tattooed skins of soldiers from France;' mummified bodies from South America; tsantsas from Ecuador; body parts in jars from Britain; and many, many more.

In one room, the extent of humanity represented. A snapshot of a collecting mania. I visited this storeroom in spring 2019, before the collections were moved out of London. I was a Medicine Galleries Research Fellow at the Science Museum, conducting research on the historical links of the museum with ancient Egyptian human remains and devising programmes for public engagement. Access to this room is restricted; I had the privilege to be allowed in. As I entered, with gloves on, I sat on the floor for a moment and looked around. The room was narrow, lined with industrial cabinets, a row of cupboards on each side, one in the middle, a small table in the centre, some more shelves on each side. All the cabinets and shelves were covered with white paper, so that one could stand in this room, unaware of the thousands of lives inhabiting this space. But I had read the 213-page list of the human remains in the care of the museum: and I knew: this was a museum graveyard, the result of the obsessive collecting of one man, and also of the collecting craze of a type of institution, the museum. I wondered, sitting on the floor to take a moment to breathe in this suddenly suffocating space, how is it possible that so many bodies have been removed from their countries and taken to this little room in the British capital? What was the rationale behind putting so many bodies in a single room - entire bodies and body parts, sometimes as small as a lock of hair, but often as violent and shocking as heads on a shelf? Why was I looking at an Egyptian mummy inside the storage space of a national science museum? And who was behind this impulse to collect the human remains of foreign people?

One man: Henry Solomon Wellcome.

To understand why two mummified ancient Egyptian bodies and numerous Sudanese skulls and skeletons made their way onto the shelves of this storeroom in London, we need to The mummy as medicine, the mummy in medicine look back in time and travel to London in the early 1900s. We must look to two areas of the city: first Westminster and then Bloomsbury.

American-born businessman and philanthropist Henry Solomon Wellcome has had an impact on medical history in many ways, first as a pharmacist, then as the owner of one of the world's largest pharmaceutical companies – Burroughs Wellcome & Co. – and also as one of the most extravagant collectors that medical history has seen. It is nearly impossible to envision the sheer number of artefacts and foreign bodies that Wellcome collected. To put it in context, Tony Gould, in Cures and Curiosities, noted that 'by the 1920s he was spending more yearly on acquisitions than the British Museum, and by the early 1930s he had five times as many artefacts as the Louvre'. At his death, Wellcome's collection is estimated to have comprised several million objects of all kinds, housed in various warehouses in London.

A small part of the enormous collection was on display at the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in London, set up by Wellcome and open between 1913 and 1932. This museum was not just a collection of medical objects, but also included anthropology, archaeology, art and other domains that reflected both Wellcome's personal interest and travels, and the European obsession with collecting 'exotic' things. The Wellcome Historical Medical Museum archival photographs show that he collected numerous human remains, including many heads that he put on display, and that he was keen on categorising medicine and other practices, with galleries of 'primitive' medicine highlighting his European bias. The catalogue of the museum, printed in two editions, for the opening and then the later reopening of the museum, notes:

The importance of museums as an integral part of teaching is now fully recognised, and, by intelligent classification and systematic grouping of objects, it is our aim and purpose to make the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum of distinct educational value to research workers, students and others interested in the subject with which it deals.

This was not just a display of objects; it was an educational tool to illustrate the different uses of medicine through time, and to highlight the superiority of some people over others. Museums have never been neutral spaces, and when it comes to the display of other people – whether it is their material culture or their bodies – the French and the British have consistently sought to prove their superiority over other customs and practices, using education, science and the museum as vehicles to promote those ideas.

So what ancient Egyptian objects did the museum choose to display, to delight and educate the visitors of the early twentieth century? We have some clues in the original museum catalogue. Egypt and Sudan were present throughout the exhibition. The guide notes that a series of objects from the excavations made by Mr. Henry S. Wellcome in a prehistoric station at Gebel Moya, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, is shown in Cases 20 -23. Wellcome travelled to Egypt and Sudan on many occasions and supervised excavations between 1911 and 1914 at the prehistoric cemetery at Gebel Moya, from which he collected skulls and human remains. Egyptian artefacts were present in various rooms: amulets, sculptures of deities associated with healing, medical papyri, stone mortars supposedly used for medical purposes and so on. The guide makes constant references to Egyptian material culture, and we know that Wellcome took an early interest in the ancient Egyptians. Lacking the educational background on this topic, he sought connections with well-known archaeologists at the time, including Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, by addressing them directly in letters:

I am very deeply interested in the origin and development of the sciences in ancient Egypt, especially in connection with Astrology, Alchemy, Medicine and Surgery, and should esteem it a great favour if you would kindly inform me of any sculptures, carvings, paintings, or papyri having reference to these subjects which there may be in the Museums or in other collections within your knowledge. I shall also be grateful to you if you can let me have any information about the early physicians of Egypt, and if you can tell me of any portraits of them. I will, of course, bear any expenses incurred in procuring the above mentioned information.

To support his research interest, Wellcome, who was incredibly wealthy, used objects as currency; and at times, these objects were human skulls.' On the death of Wellcome in 1936, the Wellcome Trust was created – to this day, it is one of the world's largest private biomedical charities. The work then began to dismantle this enormous collection, with individuals working for decades to find the objects suitable homes. Archives attest to advertisements being placed in newspapers and bulletins to ask for takers for the many artefacts, and these were dispersed amongst museums across Britain, including Bolton Museum, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and the Petrie Museum in London. Not everything was given away, however, and in 2007, the Wellcome Collection opened in Bloomsbury, with several thousand objects in its care. While some items were donated to other museums when the collections were dispersed, the Science Museum in London is today home to many of Wellcome's objects, on long-term loan – including over a thousand human remains. In particular; Henry Wellcome's archaeological excavations in Egypt and Sudan, especially in Gebel Moya, are the reason for the collection of Sudanese skulls in the Science Museum.

In London, in 2019, there were therefore Egyptian mummified bodies and Sudanese skulls in a science museum, on long-term loan from a medical museum – the bodies of real humans from long ago, displaced, stored and then shared between two British institutions. Their location at the Science Museum, which has the largest medical collection on display in the world, is not, in fact, that incongruous. Egyptian mummies, today expected in archaeological and ethnographical museums in Europe, were first and foremost part of medical collections. But their medical history does not begin as objects on display in medical museums; Egyptian mummies started their European history as medicine.

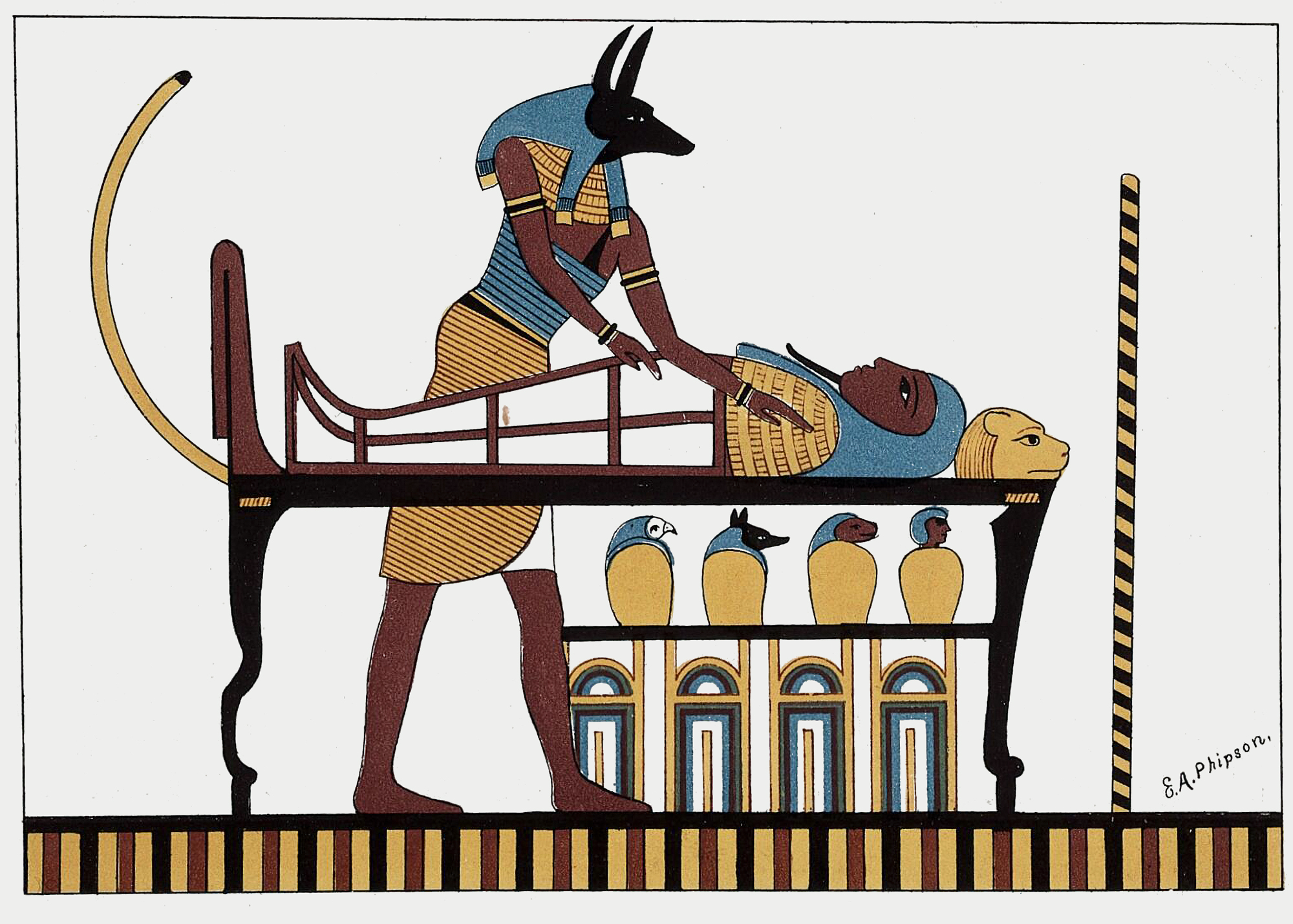

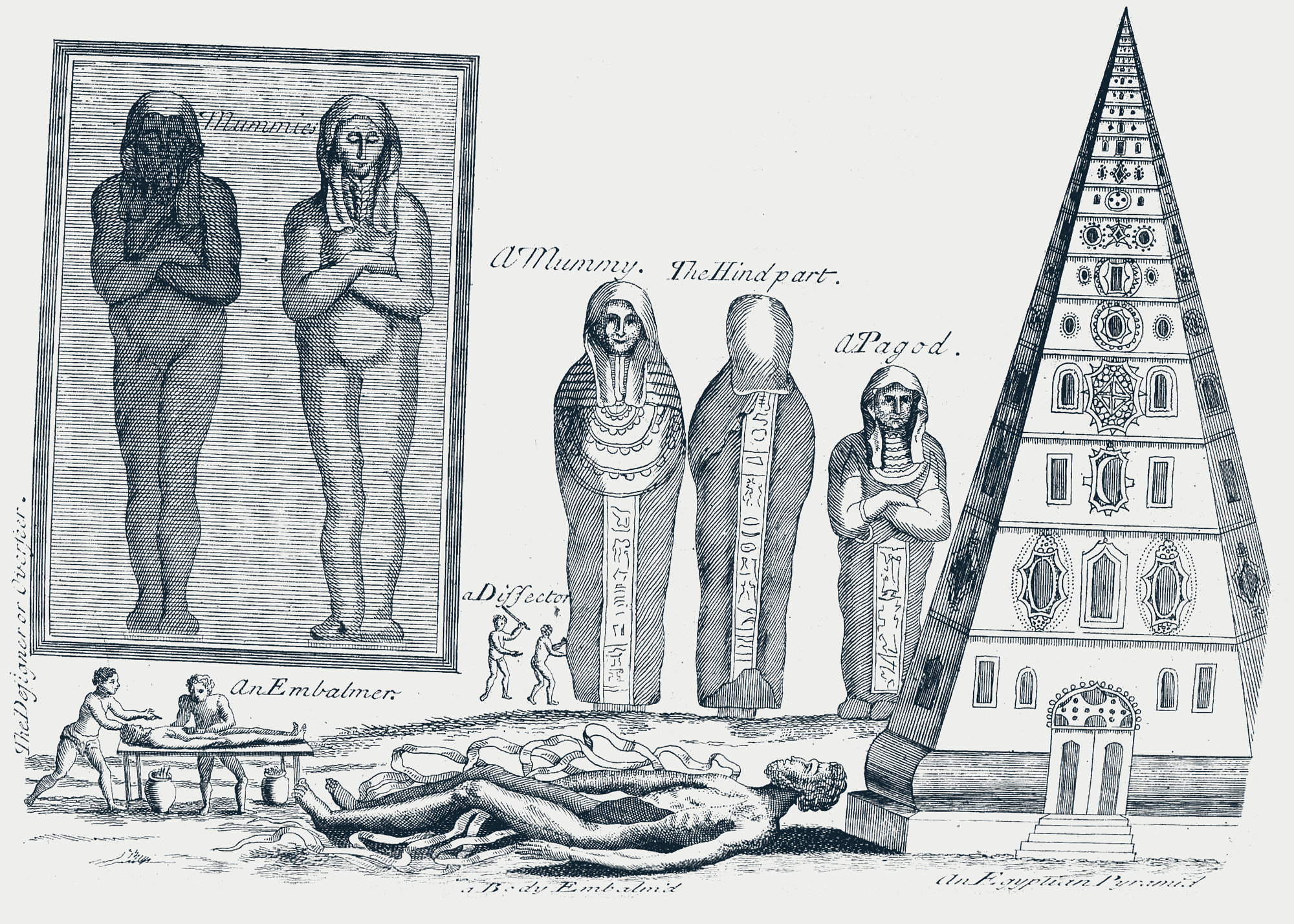

We are embarking on a journey to explore instances of Egyptian mummies being used in the natural and medical sciences. From the mumia of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, to a medical dissection in Britain, from a chemist interested in Egyptian mummies, to a mineralogist forced to unwrap a mummy by an insistent Egyptologist, to the laboratories of today where mummies are still poked around for more data, the Egyptian mummy has caught the attention of pharmacists, chemists, mineralogists, surgeons and other medical practitioners for most of its European life. This is where our journey The mummy as medicine, the mummy in medicine uncovering the European history of Egyptian mummies begins, and it sets the scene for many other interactions, up to today.

Consuming Egyptian Mummies

In Medieval Europe, Egyptian mummies were in demand. If you were sick and wealthy - the apothecary might suggest you ingest mumia, a powder made from ground ancient bodies. In Europe, mummies were medicine before they ever became museum curiosities.

In the twelfth century, a medical practitioner who lived in Cairo, Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, wrote an account about a substance extracted from the stomach and brain of cadavers that Europeans bought for half an Egyptian dirham. He recalled, 'One of the merchants selling this drug showed me a bag that was filled with it; I saw in it the chest and stomach of a corpse that was full of this mummy.' Before the Egyptian mummy was a mummy, it was first full of mummy, or mumia. The early history of Egyptian mummies in Europe is thus a surprising one: it is a story about Europeans eating the ground-up corpses of foreign bodies; of dead bodies being commercialised and used as currency; and it is also a story about how we use the word 'mummy' to denote the embalmed bodies of the ancient Egyptians, unaware of this word's unsettling origin.

But what brought people to think that Egyptian mummies could cure them?

In 1530, a coloured illustration in the Live des simples médecines, a very important medical publication by Matthaeus Platearius, showed a skeletal-looking person in a box inside a cabinet of curiosities, which included some large red coral and some shells, including one the size of a human being. The skeleton was in fact an ancient Egyptian mummy. A curious place for a mummy indeed. The publication, which was widely circulated and reprinted, noted that a mummy is found in pits of dead bodies, and that the best variety is the black and smelly one. Platearius added that the 'white' mummy, on the contrary, has no value. What exactly was Platearius talking about when he mentioned a black and a white mummy? Platearius was not thinking about ethnic origin at all, but about the embalming products used in the mummification and whether they had turned the mummy black.

When mummified bodies were first exhumed by local Egyptians and European travellers in the Middle Ages, the black colour of some mummies was assumed to be bitumen from the Red Sea. Mumiya, or mummia, is a term of Persian origin, which is also found in Arabic and refers to bitumen, and therefore these bodies were called mumia. This is where the word 'mummy' comes from. Bitumen was considered to have various healing properties, and therefore mummies were turned into a powder for medicinal use. The word 'mummy' was not attributed to the full body at first, but to this blackened substance that attracted the greed of European kings. The French King Francis I is thought to have used it to cure diseases. It was not the most popular cure in Europe, but the use of mumia was common enough to develop into a market, and fake mummies made from the corpses of recently deceased people were created to supply the demand.

Not everyone agreed on the actual benefits of the mumia.

The famed French surgeon Ambroise Paré, horrified by such a practice, dedicated an entire chapter of his Discours to Egyptian mummies, titled 'Le discours de la mumie' ('The Discourse of the Mummy'). He warned against the risks of ingesting powders derived from bodies that have been decaying for centuries: From this work one can see that the ancients were curious to embalm their bodies, but not with the intention that they served as food or drink to the living, the way they have been used until now; never did they think of such a vanity and abomination. Pierre Pomet, in his Histoire générale des rogues of 1694, dedicated a section to Egyptian mummies, highlighting his reservations as to the actual medicinal properties of mummies, and yet he noted that one must choose a mummy that is ‘beautiful, shiny, very dark, without bone nor dust, with a good smell, the smell of burning, not of pitch'! Similarly, French chemist Nicolas Lémery listed all the virtues attributed to mummies in his Traité universel des rogues simples. For centuries, therefore, Europeans were curing their headaches by drinking a powdered substance taken from the decomposing bodies of ancient Egyptians, thinking the bitumen in the embalming resins would cure their ailments. But was there really any bitumen on Egyptian mummies? Recent studies have found that for the first 2,000 years of mummification in Egypt, bitumen was in fact not used in the mummification process and only became prevalent from around 750 BC up to the Roman period. This means that quite a lot of Egyptian mummies used for their medicinal properties probably contained no bitumen at all, and individuals were simply ingesting powdered corpses ■

Mummified: The Stories Behind Egyptian Mummies in Museums

Manchester University Press, 7 June 2022

RRP: £20.00 | 288 pages | ISBN: 978-1526161895

The unsettling stories of how Egyptian mummies came to be held in British and French museums.

We all know what a mummy is – or do we? In Mummified, Angela Stienne explores the little-known stories behind the Ancient Egyptian remains displayed in British and French museums.

Taking the reader on a journey between Egypt, Paris and London, Stienne exposes a murky world of grave-robbing, theft and black-market deals over human remains. Mummies have been unrolled in public, dissected for race studies and even eaten for their supposed health-giving properties. But does the fact they are thousands of years old mean they can be treated as objects, or do we owe them the same respect we would any other human body?

Investigating matters of life and death and the ethics of collection and display, Mummified offers a fresh perspective on these ancient bodies, which have fascinated Europeans for centuries.

"This brilliantly written book proves that the mummy has reawakened within our own social spaces as a material link between past and present. A must read." – Kara Cooney

"A compelling, captivating and complete book: it takes us on a journey through which we discover, enchanted, what it is about Egyptian mummies that has captured our imaginations and the imaginations of those who preceded us." – Dario Piombino-Mascali, Research Professor in Anthropology, Vilnius University

"Fascinating and genuinely insightful reflections on the reception of the ancient Egyptian dead in museums." – Dr Campbell Price, Curator of Egypt and Sudan, Manchester Museum

Angela recommends:

⇲ The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton by Debbie Challis and Flinders Petrie (Bloomsbury Academic, 2014)

⇲ Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum by Stephanie Moser (University of Chicago Press, 2006)

Golden Mummies of Egypt: Interpreting Identities from the Graeco-Roman Period by Campbell Price (Manchester Museum and Nomad Exhibitions, 2020)

⇲ Superior: The Return of Race Science by Angela Saini (Fourth Estate, 2019)

⇲ Scattered Finds: Archaeology, Egyptology and Museums by Alice Stevenson (UCL Press, 2019)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Chris Hart at Manchester University Press.