Drugs and the Makings of the Modern Mind

Mike Jay on Sherlock Holmes and the detective's changing relationship with cocaine

In Psychonauts: Drugs and the Making of the Modern Mind, Mike Jay tells the forgotten story of self-experimentation with drugs, which was a common practice in medical science throughout the nineteenth century.

This was also the era in which psychology emerged as a scientific discipline, and the mysteries of the mind and the unconscious became a subject of popular fascination.

In this extract from the book, Jay considers Sherlock Holmes’ use of cocaine against this background. Cocaine was the great pharmaceutical success story of the 1880s, enthusiastically promoted by Sigmund Freud among others. Within a few years, however, its virtues as a stimulant, antidepressant and local anaesthetic were called into question by cases of excessive and compulsive use, often leading to nervous collapse.

The term ‘cocainomania’ was coined to describe the condition, and by 1900 the drug was disappearing from pharmacy shelves.

For full references and notes please consult the published book.

The most extended engagement with cocaine in the fiction of the late nineteenth-century came in the stories of Sherlock Holmes. Arthur Conan Doyle’s handling of the theme is an eloquent illustration of the shift in public opinion through the 1890s.

The great detective’s early adventures are the ones most liberally spiked with drug references. Initially, Holmes’s detective work seems almost to play second fiddle to his self-experiments: in the first published short story, A Scandal in Bohemia, we hear of him ‘alternating from week to week between cocaine and ambition’, until he ‘had risen out of his drug-created dreams, and was hot on the scent of some new problem’.

In The Five Orange Pips, which appeared in The Strand Magazine of November 1891, Dr Watson describes him as ‘a self-poisoner by cocaine and tobacco’. But it was the appearance of The Sign of Four in 1890, the year The Strand established itself as the leading purveyor of illustrated fiction and Sherlock Holmes as its undisputed star, that his drug habit was most memorably established.

In its celebrated opening lines:

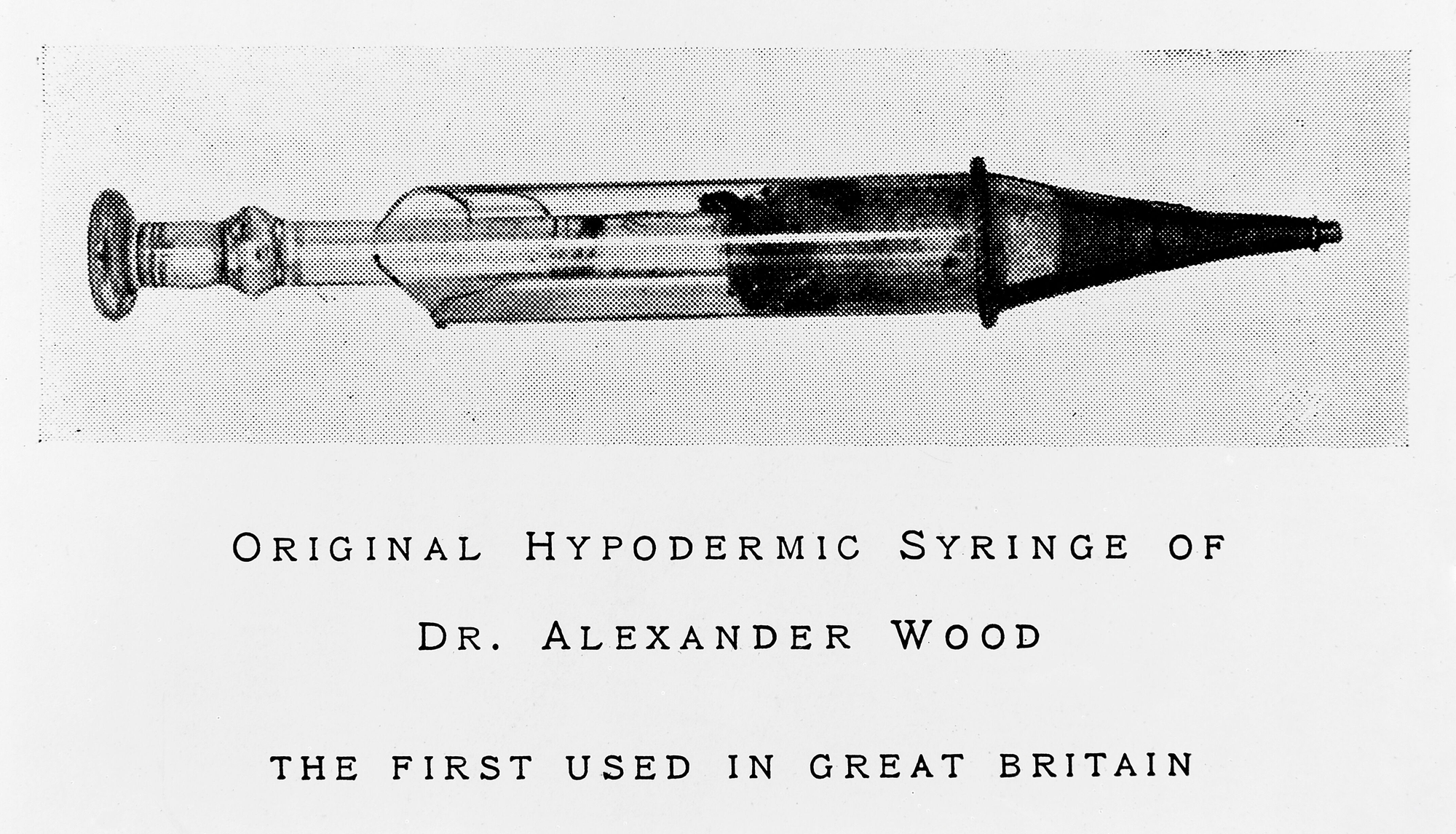

1890

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantelpiece, and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long, white, nervous fingers he adjusted the delicate needle, and rolled back his left shirt-cuff. For some little time his eyes rested thoughtfully upon the sinewy arm and wrist, all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks. Finally, he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined armchair with a long sigh of satisfaction.

‘Which is it today,’ Dr Watson asks in The Sign of Four, ‘morphine or cocaine?’ This is the only occasion on which Holmes is described as a morphine user: in subsequent stories, his habit is confined to cocaine. It may be that Doyle decided that injecting morphine seemed too much like a medical condition, whereas cocaine could be interpreted as a vice or eccentricity of character.

Still a practising doctor at this point, Doyle was familiar with both drugs: indeed, in 1891 he spent a few months studying ophthalmology in Vienna, where Karl Köller’s discovery of cocaine anaesthesia in 1884 had transformed eye surgery.

The tenor of conservative medical opinion was captured authentically in Dr Watson’s disapproving comments on Holmes’s habit – ‘it is a pathological and morbid process, which involves increased tissue-change, and may at last leave a permanent weakness’ – a serious-sounding diagnosis that is nonetheless so vague that it could refer to anything from masturbation to keeping late hours or living in the tropics. It succeeds, however, in prompting Holmes to the plainest and most enduring statement of his motivations.

‘My mind,’ he replies, rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram, or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants. But I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation. That is why I have chosen my own particular profession, or rather created it, for I am the only one in the world.'

Here Doyle places stimulant drugs at the centre of both Holmes’s professional world and his inner life. He is a brain-worker, craving stimulation but also indulging a neurasthenic and self-destructive streak. He is described elsewhere as a victim of ‘black moods’, constantly swinging from obsessive work to periods of depression – ‘in the dumps’ – where he speaks to no-one for days on end.

At the same time, Holmes is a committed aesthete: his hand-tooled injection kit marks him as a connoisseur as much as his meerschaum pipe and his Stradivarius violin. Doyle was at this time immersed in the ‘yellow’, decadent writings of Oscar Wilde, whom he met in 1889 at a dinner at the Langham Hotel in Bloomsbury hosted by J.M. Stoddart, editor of Lippincott’s Magazine, which led to the publication of both The Sign of Four and The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Holmes is a lover of art and pleasure, tantalisingly immune to public opinion; it seems likely that Doyle had Wilde, among others, in mind as he elaborated the bohemian character and lifestyle of his languid, cosmopolitan sophisticate. Holmes remains unusual among detectives in acting not out of a thirst for justice or compassion for the victims of crime, but simply a desire to keep himself amused. His detection is an art practised for art’s sake.

As the Sherlock Holmes stories grew in popularity through the 1890s, the character’s cocaine use came to suggest a seedy and disreputable edge that Doyle had not intended. In the early 1900s the Holmes stories were acquired by Collier’s, a major player in the lucrative US magazine market selling over 250,000 copies a week.

But Collier’s was concurrently running a series of investigative pieces entitled The Great American Fraud that exposed the prevalence of narcotics in patent medicines, a campaign that contributed to the regulation of the pharmacy trade by the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

A cocaine-injecting detective was out of step with the new times, and Doyle, who had in any case been mentioning his hero’s drug use less and less, took steps to terminate it.

In the short story The Adventures of the Missing Three- Quarter, published in Collier’s in November 1904, Dr Watson announced that he had successfully ‘weaned’ Holmes from the ‘drug mania’ that had threatened to check his remarkable career.

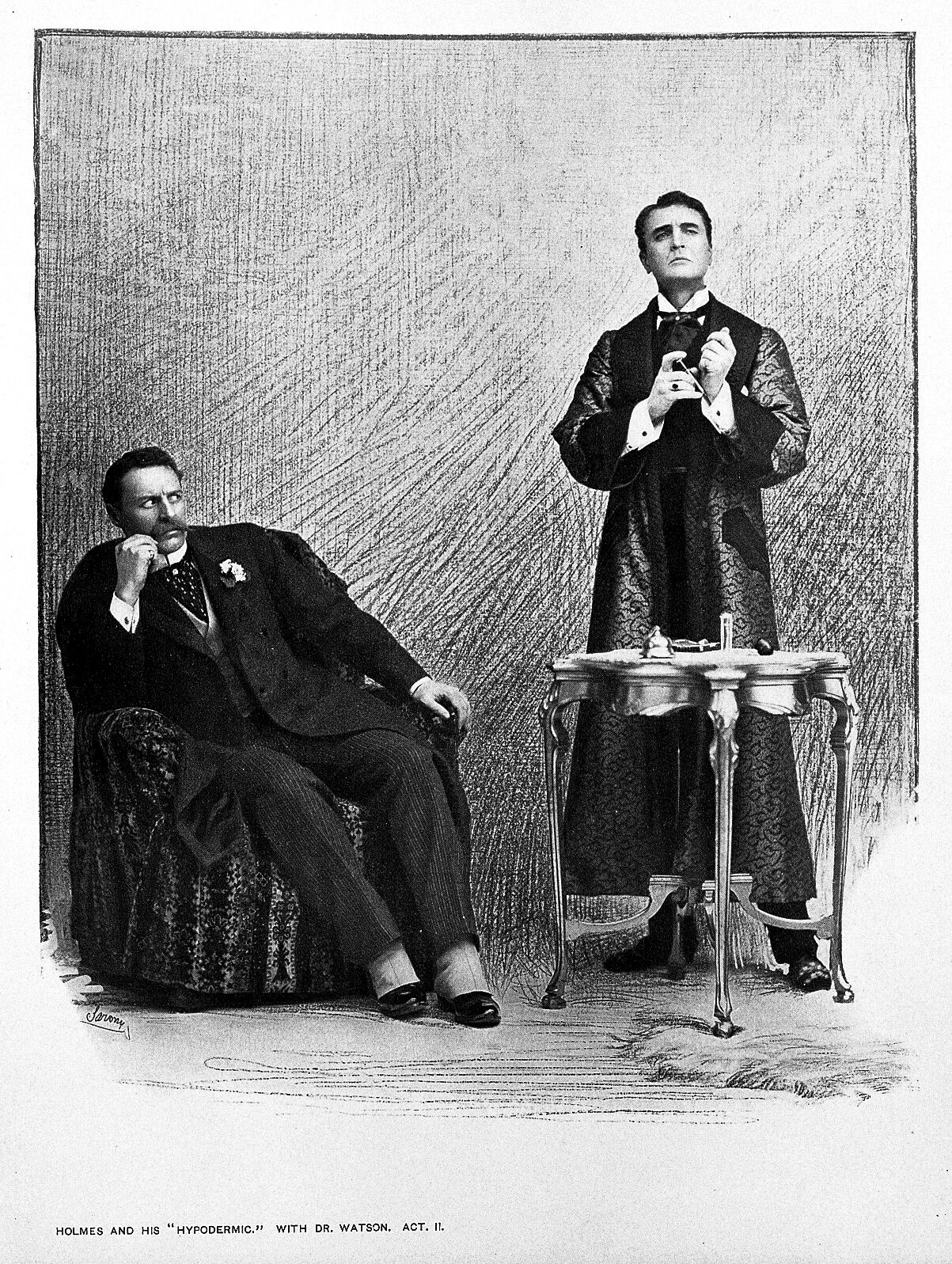

Further adjustments were made when the American actor-writer William Gillette brought Sherlock Holmes to the stage, first in the United States in 1899 and then a triumphant residency in London’s Lyceum Theatre in 1901. The injection scene from the opening of The Sign of Four was included, but the exchange between Holmes and Watson was rewritten:

1901

WATSON: These drugs are poisons – slow but certain. They involve tissue changes of a most serious character.

HOLMES: Just what I want! I’m bored to death with my present tissues and am out after a brand new lot!

WATSON: Ah, Holmes – I’m trying to save you! (Puts hand on HOLMES’ shoulder)

HOLMES: (Earnest an instant; places right hand on WATSON’s arm) You can’t do it, old fellow – so don’t waste your time.

The languorous satisfaction of Holmes’s habit is gone, replaced with the fatalistic self-pity of the doomed drug addict ■

His previous books on the history of drugs include Mescaline, High Society, and The Atmosphere of Heaven.

Psychonauts: Drugs and the Making of the Modern Mind

Yale University Press, 27 February, 2024

RRP: £10.70 | 384 pages | ISBN: 978-0300276091

A provocative and original history of the scientists and writers, artists and philosophers who took drugs to explore the hidden regions of the mind

Until the twentieth century, scientists investigating the effects of drugs on the mind did so by experimenting on themselves. Vivid descriptions of drug experiences sparked insights across the mind sciences, pharmacology, medicine, and philosophy. Accounts in journals and literary fiction inspired a fascinated public to make their own experiments―in scientific demonstrations, on exotic travels, at literary salons, and in occult rituals.

But after 1900 drugs were increasingly viewed as a social problem, and the long tradition of self-experimentation began to disappear.

From Sigmund Freud’s experiments with cocaine to William James’s epiphany on nitrous oxide, Mike Jay brilliantly recovers a lost intellectual tradition of drug-taking that fed the birth of psychology, the discovery of the unconscious, and the emergence of modernism. Today, as we embrace novel cognitive enhancers and psychedelics, the experiments of the original psychonauts reveal the deep influence of mind-altering drugs on Western science, philosophy, and culture.

"Fascinating book . . . not something you get taught at school" – The Guardian

"Jay is a leading expert on the history of Western drug use, and Psychonauts is the latest in a series of excellent studies in which he has investigated the roots of a kind of psychoactive exploration that we tend to associate with the nineteen-fifties and sixties" – New Yorker

Additional Credit

Wih thanks to Yale University Press