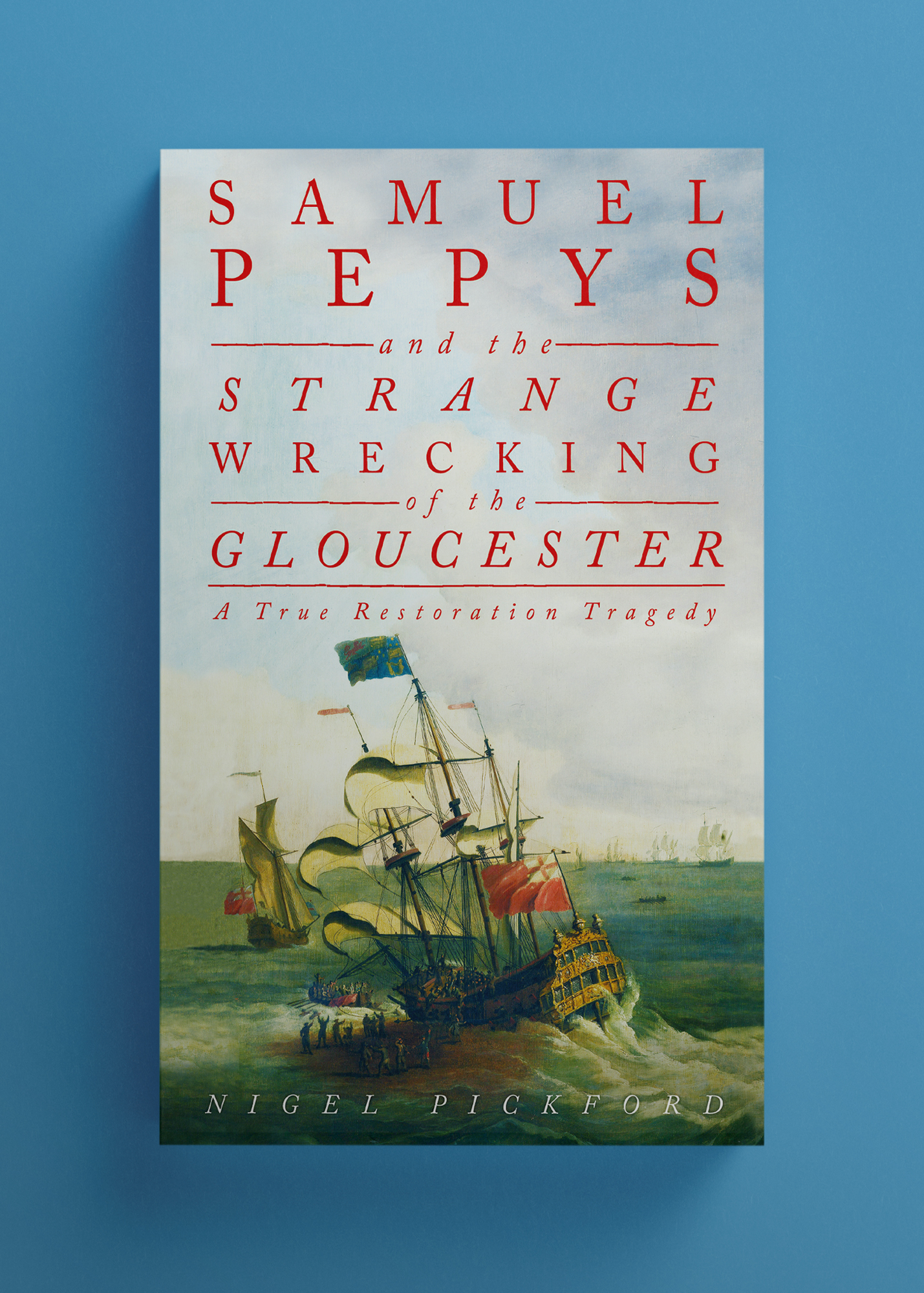

Excerpt: Samuel Pepys and the Strange Wrecking of the Gloucester

A True Restoration Tragedy

In 1682, Charles II invited his scandalous younger brother, James, to return from exile. To celebrate, the future king set sail in a fleet of warships destined for Edinburgh. Yet disaster struck en route, the royal frigate carrying James and his entourage sank. The diarist Samuel Pepys had been asked to sail with James but refused the invitation, preferring to travel in one of the other ships. Why? What did he know that others did not?

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Nigel Pickford

On the 3rd of May 1682 a fleet of warships and royal yachts assembled off Margate at the mouth of the Thames. In full sail they made an impressive sight which is exactly what James, Duke of York, and Admiral of the fleet, required. He had at last, after nearly three years of semi exile, firstly in Brussels and then in Edinburgh, finally been given permission to bring his pregnant wife back to Whitehall and settle once again in London. King Charles II, increasingly aware of his own mortality and lack of legitimate children, was anxious to have James, his younger brother and appointed heir, once again at the centre of government, despite James’ openly Catholic faith, which had acted as a lightening rod for the more extreme puritan opposition.

The Scottish fleet was intended to symbolize James’ return to power and martial prowess. It didn’t quite turn out like that. On the morning of May 6th, in clear light and good weather, the Gloucester, on which James was travelling, together with a large retinue of his closest supporters, aristocrats, business men, lawyers, scientists, musicians and huntsmen, crashed into a sandbank and sank. Nearly two hundred people drowned, including many ordinary sailors.

The tragedy of the wrecking was quickly followed by the most intense controversy about who was to blame, a controversy which has continued to rage down the centuries.

— Nigel Pickford

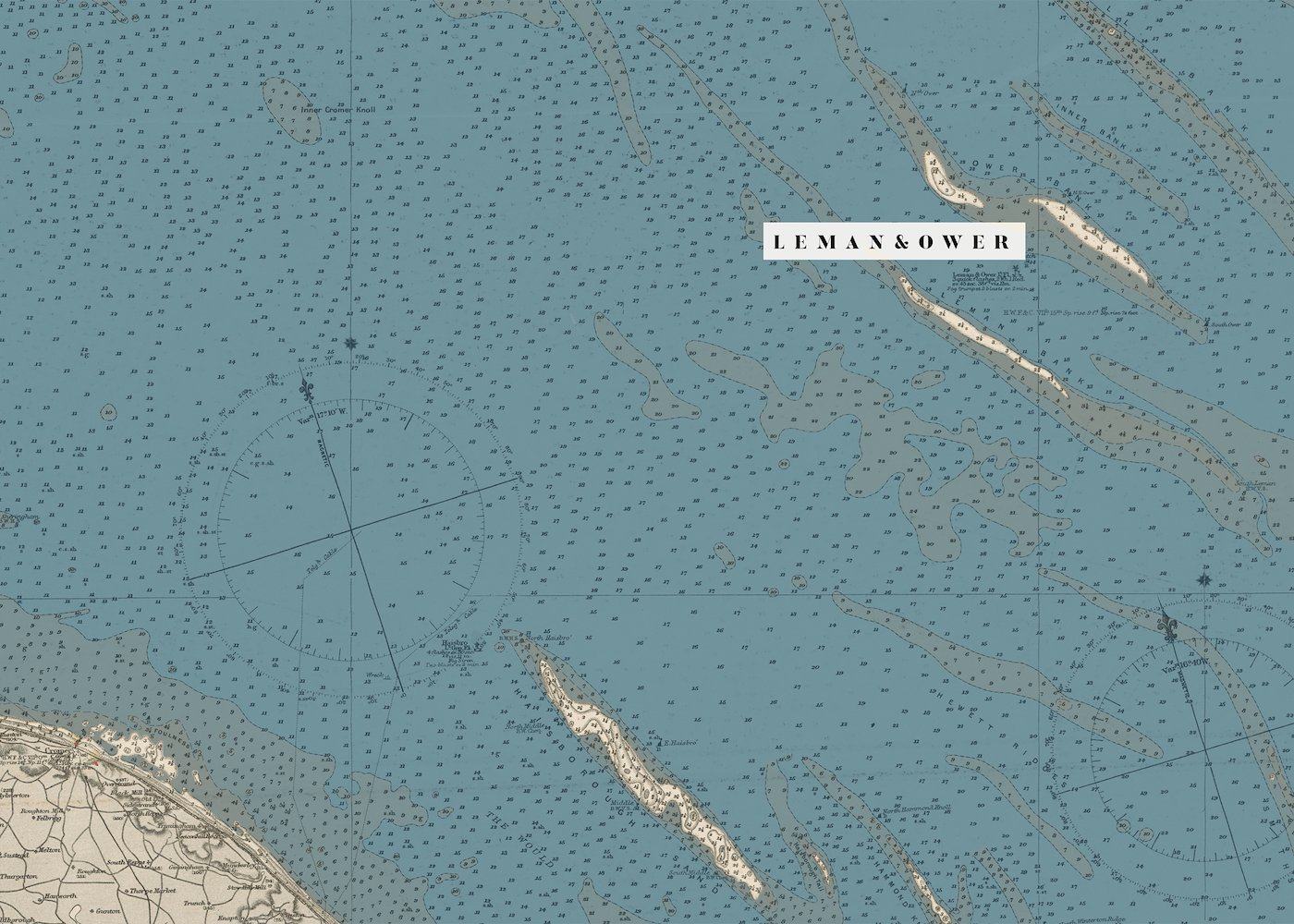

The Norfolk Coast

An excerpt from Samuel Pepys and the Strange Wrecking of the Gloucester

At first the bodies sank to the seabed. Then, after only a few days of submersion, once the internal organs had begun to putrefy and the flesh had swelled with noxious gases, they rose again to the surface like inflated balloons. Later that same week they came ashore one by one and at different locations, as if in death they disdained each other’s company. They fetched up all along the bleak and empty coastline that stretches from Yarmouth to Caister, Winterton and Happisburgh. There were even some that drifted as far north as Foulness and the estuary of the Humber.[1]

They were deposited on the sands as the tide ebbed. In some, the softer parts, the cheeks and the lips, had been eaten away by lampreys and hag fish. But there were no obvious signs of human violence, no gaping wounds. The waves nudged and licked at their ankles, alternately fawning and spurning.

It was the middle of May 1682. The weather was thick and often raining with blustering easterly winds that kept the temperatures unseasonably low. The wind moaned through the grey hair grass that grew luxuriantly over the sand dunes. The booming call of the bitterns was like the sound of distant cannon fire, both a warning and a requiem.

Shipwreck was common in these waters, and Newarp and Scroby Sands were both notorious graveyards for sailors. But usually there was some evidence of the ship itself, a standing mast or a floating spar, and the number of victims was not so numerous. On this occasion the absence of wreckage and the wide dispersal of corpses suggested that a great ship had gone down far out to sea. But there was no war raging and there had been no storm, so there was no obvious reason for a ship to have perished.

It was the scavengers of the coastline, the cockle pickers and the samphire gatherers, peering into the grey light of dawn, who first spotted this strange invasion of the dead. Most of the bodies still had strips of coarse blue cloth attached to them. There was even the odd telltale red hat washing back and forth in the slack water. It all spoke of a Royal Navy ship. The bodies were hurriedly searched for valuables. Shipwreck was looked on as part of God’s beneficence by those who lived along this forlorn coast, far from the eye of the magistrates. Daniel Defoe in his Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain remarked on how:

As I went by land from Yarmouth northward, along the shoar towards Cromer … I was surprised to see, in all the way from Winterton, that the farmers, and country people had scarce a barn, or a shed, or a stable; nay, not the pales of their yards, and gardens, not a hogstye, not a necessaryhouse, but what was built of old planks, beams, wales and timbers, &c. the wrecks of ships, and ruins of mariners and merchants’ fortunes.

One or two of the corpses were sumptuously dressed, suggesting members of the gentry were among the drowned. They offered rich pickings for those who found them. The quickest and surest way to obtain a gold ring was to sever the finger on which it had become embedded.[2]

For the most part the dead could not be identified. They were wrapped in a simple shroud, placed on the backs of carts and buried in a common grave in the nearest churchyard. There was no bell, no book, no prayer, no distribution of ale and cheese to mourn their passing. It was important to keep the cost to the parish to a minimum. But in certain cases the names of the missing can be traced through the letters of survivors, the evidence of wills or the ex gratia payments made to widows.

Rowland Rowleson was one of the ordinary sailors who lost their lives when the Gloucester frigate sank, for that was the name of the Royal Navy ship that had foundered some 30 miles from the nearest land. He had made his will just two weeks before he sailed:

Know all men by these words that I, Rowland Rowleson belonging to his Majestie’s Ship called the Glocester Sir John Berrie Commander have made ... Hercules Browne of Wapping Whitechappell … slop seller my true and lawful attorney … and further considering the dangers and perils of the Seas and the uncertainty of my returne for the avoidance of variance and strife which may happen about that small estate which I shall leave at the time of my decease ... do give unto Hercules Browne my said attorney all my wages debts moneys ... goods chattels and estate whatsoever and do make the said Hercules Browne sole executor ... whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seale the 19th day of April in the 34th year of Charles the second King of England Scotland France and Ireland in the year of our Lord God one thousand six hundred and eighty two, Rowland Rowleson, his mark...

His use of the phrase, ‘considering the dangers and perils of the Seas and the uncertainty of my returne’, has, in the circumstances, a grim poignancy. Did he make this will because he had a premonition of his own death? Was there talk among the sailors of Whitechapel and Wapping, Stepney and Shadwell that the Gloucester was a cursed ship? It is not out of the question. There were already rumours that James, Duke of York, would be sailing on the Gloucester to fetch back his pregnant wife, Mary of Modena, from Scotland with the intention of then settling in Westminster, where he was expected to take over much of the running of the state.

Certainly, no sooner was it known that the ship had sunk than there were those who were saying that the wrecking was all part of a plot carried out by the Fanatick Party, with the explicit aim of drowning James. It was claimed that at the centre of this supposed plot was Captain Ayres, the Gloucester’s pilot. A Mr Ridley wrote excitedly to Sir Francis Radcliffe of Dilston, ‘I must inform you that the pilot is a known Republican ... it’s not only suspicious but evident he designed his [James, Duke of York’s] ruin with the whole ship, having made a provision for his own escape, but he is taken and will be tried for his life.’

But there is another equally compelling explanation as to why Rowleson felt it necessary to make his will. It is an intriguing document, as much for what it doesn’t say as for what it does. Rowleson was obviously a man very much alone in the world. He makes no mention of a mother or a wife, a child or a lover, or even a friend. Instead he makes Hercules Browne, simply referred to as a slop seller in Whitechapel, both his attorney and his sole beneficiary. He may have been an orphan or simply old, indigent and solitary. What is very strange is that a man in Rowleson’s situation, a man with only a ‘small estate’ to dispose of, as he himself frankly described it, should bother to make a will in the first place. The most probable explanation for this meticulous ordering of his affairs before he set sail is that he owed Hercules Browne money and that it was Browne who had insisted on the will being made before he agreed to advance him any further credit. Slop sellers sold sailors their clothing, their canvas jackets and trousers, along with other small necessaries, quids of tobacco for a clay pipe, or dice carved from bone for playing backgammon

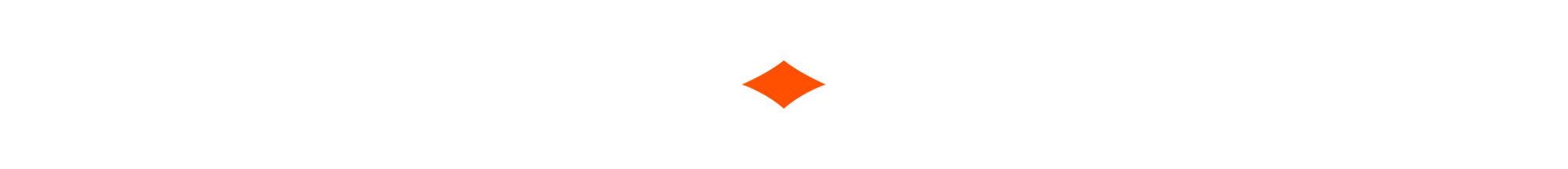

The Leman and Ower

From 10 p.m. on Friday, 5 May, until 4 a.m. the next day, the small fleet of yachts and the two warships, the Happy Return and the Gloucester, sailed north-north-east and north by east. It was a rough night with a strong wind blowing from the east. Lieutenant Wetwang, on the Happy Return, refers to it as a ‘stiff gale’. The ships made good progress in the darkness. According to Wetwang, they covered 12 leagues in the six hours, which is the equivalent of 36 miles or a speed of over 6 knots. This was a fast rate for a seventeenth-century sailing ship, particularly at night. According to Sir John Berry in the Gloucester and Christopher Gunman in the Mary, there was a slight shift off course at 2 a.m. from north by east to north. Wetwang does not mention it, which may explain why by 4 a.m. the Happy Return was ‘to the windward’ of the Gloucester – that is, further out to sea. Both Wetwang and Berry mention a further shifting of the course at 4 a.m. towards the north north-west (Berry) or north by west (Wetwang). This final change – the last before the fatal collision with the sandbank – was ordered by Ayres who, according to Captain John Berry’s account, ‘affirmed that this course would carry the ships out of all danger, and that we were past the Lemon and Oare [Leman and Ower]’. The unfortunate Ayres could not have been more mistaken.

By 4 a.m., dawn had already broken. Gunman went below on the Mary yacht to get some rest. He had been on continuous duty for nearly twenty hours. He instructed his first mate, William Sturgeon, to come and call him should they come into shoal water. The Mary was out in front of the other ships. Ayres, on the Gloucester, also went off duty.

At 5 a.m., the linesman on the Mary cast his rope with a lead weight attached, marked with knots at regular intervals, and was shocked to discover a depth of only 7 fathoms. Gunman was sent for. He immediately realised the terrible danger they were in and ordered the helmsman to bear away to the west. The water depth quickly increased. Gunman then signalled to the Gloucester by waving the Union Jack seven times at the stern of the poop deck. Seven times indicated the depth of water of 7 fathoms. It had been daylight by then for nearly two hours and so the signal should have been clearly visible, but it was a little strange that Gunman did not also fire a warning cannon.

At first, the Gloucester appeared to follow the Mary towards the west, but in a very short space of time Gunman observed that the flagship was aground and beginning to fire guns, both as a signal of distress and as a warning to the rest of the fleet. All sources agree that at the moment the Gloucester struck, the Mary was sailing ahead on the larboard, that is the left hand or west side, of the Gloucester. The distance between the two ships was variously estimated as being somewhere between half a mile and one and a half miles.

In his ‘Narrative’, Sir John Berry makes no mention of observing the Mary either bearing off to the west or waving a flag of warning. But then he makes no mention of the Gloucester firing warning guns for the rest of the fleet, which it clearly did for they were heard both on board the Mary and on the Happy Return. Lieutenant Wetwang states that they heard ‘a gun and then another’, and observed that the Gloucester also ‘put out a waft’, a flag of distress. If it had not been for these timely warnings the Happy Return would very probably have suffered a similar fate to the Gloucester, for it was following about half a mile astern. As it was, they were sailing at such a speed that it was no easy business to turn or ‘wear’ the ship. Wetwang provides a graphic description of the difficulties, ‘Claped astays’, that is tacked bringing the head of the ship into the wind, ‘but would not stay, and had 7 fathom, so flatted in the head sails’, to take some of the wind out of them, ‘and hauled up the main sail and lowered the main top sail and in wearing had 9 fathoms and then 17 fathoms. So brought round to and came to anchor.’ It was a close thing.

Those on the Gloucester did not have the benefit of any advance warning. According to Sir John Berry, the linesman had ‘just before sounded and had twenty fathom water’ when the ship ‘run ashore upon the west part of the Lemon [Leman]’. He made the time 5.30 a.m., which is exactly what Wetwang made it. Gunman recorded the time as being 5 a.m. in his journal. He then changed it to 5.30 a.m. in his later report on the sinking, which was called ‘An Abstract of Gunman’s Cause’.

Sir John Berry provides the greatest detail as to what happened next. The Gloucester did not just strike the sandbank and come to a shuddering halt. Instead, it ‘beat along the sand, not sitting fast. Whilst our rudder held, we bore away West, and upon every lift of the sea went off.’ In other words, it was bouncing along the top of the sandbank, coming clear at every lift of the wave and crashing back down in the troughs. At this point there must still have been a strong hope that the Gloucester would pass over the ridge of sand and into deep water on the other side without serious mishap.

Hitting sandbanks was not unusual for a sailing ship; in most instances they survived without incurring fatal damage, as, for example, with the Ruby on the Galloper just two days previously. One of the problems for the Gloucester was that immediately before impact it had been running before a strong wind. It had probably been sailing at a speed of 6–8 knots. In addition, the Leman and Ower banks are very solid ridges of sand. The impact would have been considerable, for there had been no opportunity to slow the ship beforehand.

Sir James Dick, Lord Provost of Edinburgh, was a passenger aboard the Gloucester. His letter of 9 May to Mr Patrick Ellis, a merchant in London, graphically underlines the violence and shock of that initial collision, ‘the helm of the said ship having broke, and the man being killed by the force thereof, at the said first stroke’. In other words, the impact caused such a wrenching of the tiller that the man in charge of it had been crushed to death by the whiplash effect.

For some minutes the Gloucester continued to move in a westerly direction, still bumping along the surface of the ridge. The fact it was scraping along the top suggests that it must have hit the bank where there was approximately 3 fathoms of water over it at low tide. The Gloucester had a draught of 17ft 6in. ‘At last,’ continues Sir John, ‘a terrible blow struck off the rudder, and, as I apprehended struck out a plank nigh the post, which made eight feet water in a moment’. The word ‘post’ refers to the central structural timber at the stern of the ship, and 8ft is the depth of water that immediately flooded into the holds. The pumps were employed and materials for baling but it was already too late, ‘the government of the ship being lost’ now that the rudder had gone. The water rapidly increased ‘as high as the gun deck’ and the ship continued to beat along the sand, ‘her head being cast about to the S.W. by W’.

By this stage it would probably have been best to try and anchor on the bank in an attempt to stabilise the movements of the ship. ‘However, the lifting of the sea forced her off the sand, and she went into fifteen fathom water, before we could let go one anchor, which proved the loss of many poor men’s lives.’ Once in deep water they did succeed in letting go the anchors:

We anchored and brought her up almost head to windward, we still working with our pumps and baling, but to no purpose: the water increased so fast, that before the boats could take off the men, (though there was great diligence used) the ship sunk, and several of our men perished with her, myself hardly escaping by a rope over the poop, into Captain Wyborne’s boat.

It would doubtless have been better for all those concerned if the Gloucester had remained stuck on the sandbank. It would very probably still have wrecked, but it would have been a much slower process, allowing for a more orderly disembarkation. Sir James Dick remarked on this with his usual common sense:

Now if she had continued on the three fathom, and broke in pieces there, all would have had time to save themselves: but such was the misfortune, that she wholly overwhelmed and washed all into the sea that were upon her decks expecting relief by boats which certainly would have been if she had but staid half an hour more.

Sir John Berry does not state how long it had taken from the moment that the Gloucester first struck until it sank, but Lieutenant Wetwang as usual supplies the missing detail: ‘At a quarter past 6 oclocke sunke downe in 16 fathom the mizen top mast head just above water, being just upon high water.’

It had been forty-five minutes from beginning to end. It was not much time for organising the sailors into doing what they could to try to save the ship, overseeing the evacuation of the duke and his entourage and finally saving their own lives, especially when one takes into account that when the Gloucester first struck most of those on board would have been asleep. Gunman, in his journal, agrees with Wetwang’s estimate of forty-five minutes, ‘And of all sorts there were above 150 men drowned, and all in less than three quarters of an hour.’ Samuel Pepys, in his letter to W. Hewer, also remarks on the brevity of the time between ‘when she struck’ and ‘her final sinking’, stating that ‘there passed not, I believe, a full hour’ ■

1. Foulness was a village to the east of Cromer in Norfolk that has now been lost to coastal erosion; London, 17 May: ‘We hear the boats sent to careene off the mouth of the Humber, have taken up the dead bodies of several persons in the late wreck of the Glocester Frigate, amongst whom are some persons of quality’. Yarmouth, 16 May: ‘This morning two sailors were cast upon this shoare supposed to perish at the late dismal Wracke upon the Lemon-Ore, about 20 leagues from this place, and we hear that the bodies of several others have been taken up at other places, being by the tides left upon the sands’, The Domestick Intelligence.

2. When the Association was lost off the Isles of Scilly on 22 October 1707, the body of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, who was among those drowned, was discovered with the ring finger cleanly severed.

• Daniel Defoe, A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (London: Penguin, 1978);

• Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, Prob/11/370 TNA;

• Impartial Protestant Mercury, 12 May 1682;

• Calendars of State Papers Domestic (CSPD), E. Ridley to Sir Francis Radcliffe, Dilston;

• ADM 51/4214 Logbook of the Happy Return;

• Berry, ‘Narrative’, in Singer (ed.), The Correspondence of Henry Hyde;

• Henry Ellis, Original Letters, Vol. IV (London: Harding, Triphook and Lepard, 1827);

• JARVIS IX/1/A/5;

• Pepys to W. Hewer, 8 May 1682, in Howarth (ed.), Letters and the Second Diary of Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys and the Strange Wrecking of the Gloucester

The History Press Ltd, 30 September 2021

RRP: £20.00 | 304pages | ISBN: 978-0750997539

In 1682, Charles II invited his scandalous younger brother, James, Duke of York, to return from exile and take his rightful place as heir to the throne. To celebrate, the future king set sail in a fleet of eight ships destined for Edinburgh, where he would reunite with his young pregnant wife. Yet disaster struck en route, somewhere off the Norfolk coast. The royal frigate in which he sailed, the Gloucester, sank, causing some two hundred sailors and courtiers to perish.

The diarist Samuel Pepys had been asked to sail with James but refused the invitation, preferring to travel in one of the other ships. Why? What did he know that others did not? Nigel Pickford’s compelling account of the catastrophe draws on a richness of historical material including letters, diaries and ships’ logs, revealing for the first time the full drama and tragic consequences of a shipwreck that shook Restoration Britain.

"Fascinating ... Pickford, a historian who also has experience as a consultant for salvage companies, offers an expert study of the actual circumstances of this shipwreck." – Margarette Lincoln, author of London and the Seventeenth Century

"A thoroughly-researched and detailed history book yet has the structure and pace of a novel ... It makes for an informative, engaging, entertaining and enjoyable read." – The History of London

Nigel recommends:

⇲ The Making of King James II by John Callow (Stroud, Sutton Publishing 2000)

⇲ Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1773 by Peter Earle (London, Methuen 1998)

⇲ London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration until the Exclusion Crisis by Tim Harris (Cambridge, CUP 1987)

⇲ The First Whigs. The Politics of the Exclusion Crisis, 1678-1683 by James Rees Jones (Oxford, OUP 1961)

The Wooden World by N. A. M. Rodger (London, Collins 1986)

Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self by Claire Tomalin (London, Penguin 2003)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Also Featured On

Travels Through Time Podcast: The Strange Wrecking of the Gloucester with Nigel Pickford (1682)

Additional Credit

With thanks to Graham Robson and Flint Books (The History Press)