Excerpt: Scarlet Town by Leonora Nattrass

1796. A rigged election. A town at war. A murderer at large.

Ethel Smyth. Rebecca Clarke. Dorothy Howell. Doreen Carwithen. In their time, these women were celebrities. They composed some of the century’s most popular music and pioneered creative careers; but today, they are ghostly presences, surviving only as muses and footnotes to male contemporaries like Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Britten – until now.

Leah Broad’s magnificent group biography resurrects these forgotten voices, recounting lives of rebellion, heartbreak and ambition, and celebrating their musical masterpieces. Lighting up a panoramic sweep of British history over two World Wars, Quartet revolutionises the canon forever.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Leonora Nattrass

Scarlet Town is the third novel in my Laurence Jago historical crime series. It is set in the Britain of the 1790s, with a wartime government paranoid that the recent French Revolution might be re-enacted here. There is so much that is familiar about this period of history, when our modern ideas of human rights and democracy first crystallised and political debate became recognisably about the issues which still divide us.

Each book in the series is designed as a standalone story. We first meet Laurence in Black Drop. He is a Cornish farmer’s son and Foreign Office clerk, who has been decoding messages in the Downing Street attic for ten dull years. His investigation into leaked military information and the death of another clerk takes him through an eighteenth-century London landscape of anatomists and menageries, political journalism and revolutionary societies.

The second book, Blue Water, sees Laurence liberated from Downing Street, aboard the Tankerville mail ship, en route to Philadelphia. He is carrying a vital treaty that is aimed at keeping the Americans out of the war on the French side. Laurence’s colleague dies in a strange ‘accident’, the treaty disappears, and he finds himself trapped aboard with a possible murderer and a dancing bear.

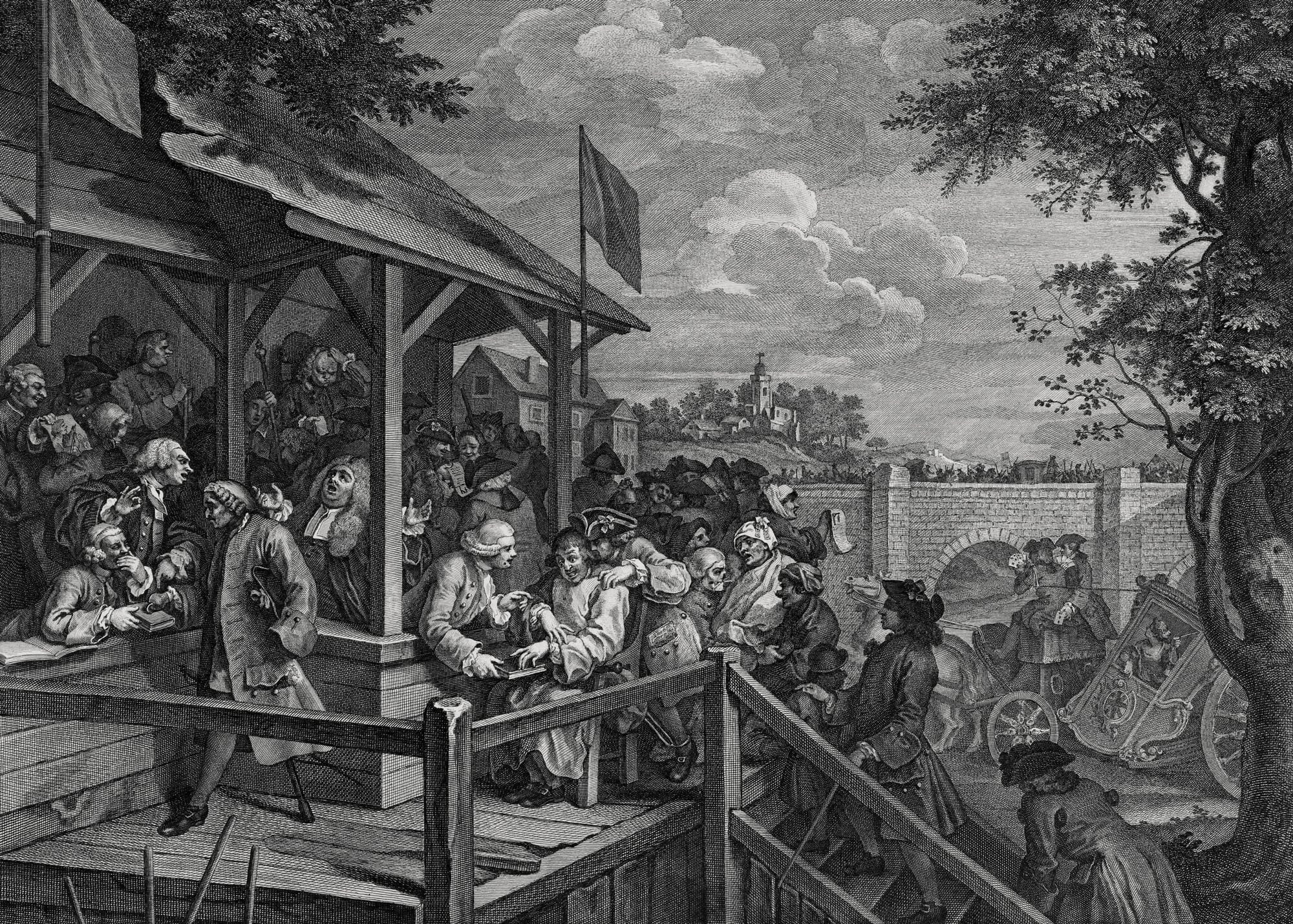

In the latest book, Scarlet Town, Laurence arrives home in Cornwall, to find a general election in progress. His home town of Helston has only two octogenarian voters who are responsible for returning the town's two MPs to Parliament. But a rival group, led by the mayor, has set up an alternative electorate and the town has divided into fierce warring parties. In the opening chapter, Laurence arrives in Helston in the middle of a bad-tempered hustings…

— Leonora Nattrass

It was gone eight o’clock, and the last rays of sunlight slanted between the buildings on Meneage Street, illuminating a rash of vivid silk ribbons in the hats of the crowd. We were swaying down the narrow road through such a throng it frightened the horses. They jibbed in the shafts and made the whole coach judder in a thoroughly disagreeable manner.

My mind skipped to the coach roof, piled high with our belongings, and I imagined in some morbid detail the top-heavy vehicle toppling over. But I comforted myself with the reflection that though this would be unpleasant for those of us within, it would be far worse for the multitude without, who were pressing against the sides of the vehicle, their faces coming and going as they peered in at us.

But of course, I was alone in such fears. ‘Party colours,’ was all Philpott was saying, in a marvelling tone. ‘Laurence, what the devil is afoot? I can see blue ribbons and red ones, too, whatever they may signify.’

Parliament had been dissolved, we had heard on landing at Falmouth, and a general election had been called. My home town of Helston being an egregious example of a rotten borough, Philpott had declared an immediate intention to put off his return to London by a week and linger in Cornwall to report on the town’s shocking corruption for his newspaper, the Weekly Cannon. There were only two old voters left, the rest having died off over a long number of years, and the remaining two were firmly in the pocket of the town’s patron, the Duke of Leeds, who told them who to vote for and no doubt paid them some little sum for their trouble. This having been the case for many years – only the number of old electors inevitably dwindling – we had expected to find the town in its usual state of drowsy repose.

Instead, we were arrived in the middle of a noisy political meeting. The blue silks Philpott had noticed were certainly the Duke of Leeds’ colours, but the scarlet red of their opponents was new to both of us. And there was something else generally strange about the whole scene that I could not, as yet, quite put my finger on.

Philpott looked entranced by the roar of laughter, screams and angry shouts magnified by the walls of the narrow street, while his wife was busy rebuking William Philpott junior for gurning back at the gawking faces beyond the window. Margaret, Philpott’s eldest daughter, was now seven years old and growing dignified. The other small Philpotts formed an undifferentiated mass of shrill voices and writhing limbs, which I generally endeavoured to ignore as best I could.

The crowd was thickening and, thwarted of all further progress, the coach ground to a halt. A moment later the coachman’s face appeared at the window. ‘I can’t get no further,’ he said. ‘You’ll have to get out here. The Angel’s only an ’undred yards further on, round the corner.’

Philpott took this news stoically and, if he showed any hesitation at disembarking in the midst of such a riotous crowd encumbered by his luggage, his wife and his six children, it was only that of a man set on braving a tiger and calculating the safest way to do it.

‘Pass the brats out to me, will you, Laurence?’ he decided after a moment, leaning out of the window to get at the door handle. ‘Hand in hand, I think will be best. Nancy my dear, you come last and for God’s sake don’t let go or we shall scatter like shot and the children will all be trampled to death.’

This was not a very encouraging idea to infant minds and they squawked with alarm as I funnelled them through the door and down the carriage steps to their father, who braced himself against the tide of bodies with his stout frame and gathered his brood about him like a mother hen. Mrs Philpott went last, with one infant on her hip and clutching another by the collar. I thrust my eyeglasses more firmly up my nose before stepping down from the coach behind her. A man pushed past me roughly and I staggered back, banging my head painfully on the door handle. Meanwhile, the coachman had scrambled up to the roof and was handing down our luggage, a vast pile of boxes and bags we had brought with us hurriedly from America and which now formed a whole new obstruction in the crowded street.

Though we were out of the coach, we were so hemmed in by bodies there was no possibility of further progress either forwards or back, especially with our luggage and clutch of small Philpotts in tow. And a strange new wave of movement was now approaching up the street, accompanied by shouts and screams that verged on panic.

The crowd parted to reveal a posse of running men, mouths horribly agape in blood-red painted faces. They were in some strange ecstasy beyond noticing pain or fear as they bore down on us, wildly drunk. The Philpott children shrieked again as the running men slammed into the coach, and the coachman shouted an angry reproach from his spot on the roof. One of the front horses reared in its traces and the crowd flowed, perhaps afraid the huge vehicle really would topple. The drunk men bounced off again – one of them now bleeding briskly – and swept into a doorway to our left. It was the Rodney Inn, where I had spent some discreditable evenings in my youth, and I well recognised the solemn naval captain on the inn sign gazing down with disapproval at the turmoil unfolding below him.

It now became clear that the whole crowd was converging on the Rodney and had blocked the street, being far too many to enter. There were shouts coming from inside the inn, and even over the general racket I could hear the dull thuds and thumps of drunken affray. The scarlet-painted men would hardly be welcome but would be equally hard to be rid of.

Other men without party colours were hastening out of an alley beside the inn, buttoning their breeches, come from the privy. I recognised one or two of them as my mother’s farming neighbours, probably come into town to witness the excitement but only adding to the general disorder.

There were more shouts from inside the Rodney, followed by a sudden and rather bruising exodus. The innkeeper, possibly fearing a fatal crush, was driving everyone out. The crowd around us flowed again and one of the infant Philpotts came adrift from its mooring and was swept away by the current.

If I had been as careless as Philpott had proved in the heat of our flight from Philadelphia I might have let it go by. But being a man of more sense than my employer, I scooped it up as it passed me and set it on my shoulders. In front of us, a woman’s bonnet was knocked off her head and she gave a yelp of anguish to see it trodden underfoot. Then, finally driven out of the inn, the group of painted drunks landed at my elbow. Their knuckles were as red as their faces now, and they were clearly itching for another fight. Whether I was to be their next victim was entirely out of my hands for I could not move a step in any direction nor let go of the child on my shoulders.

Just then, as the clock tolled from the crossroads beyond the knots of argumentative bodies, we heard louder screams and shouts coming from the same direction.

‘Fire!’ a voice was shouting. ‘Fire at the Guildhall!’

And as if God had taken his broom to the gathering, the whole crowd was swept summarily along the street, parting around our heaped-up luggage as Philpott, his wife and I crouched about the children to keep them safe. Ahead, another voice was shouting.

‘Will the doctor come to the Guildhall? The elector Thomas Wedlock is dead.’ ■

Excerpted from Leonora Nattrass's Scarlet Town

Her first novel, Black Drop, was a Times Book of the Year and her second, Blue Water, was a Waterstones Thriller of the Month and longlisted for the Theakston Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year Award and the CWA Historical Dagger.

Scarlet Town

Viper, 5 October, 2023

RRP: £16.99 | 320 pages | ISBN: 978-1800816961

1796. A rigged election. A town at war. A murderer at large...

Disgraced former Foreign Office clerk Laurence Jago and his larger-than-life employer the journalist William Philpott have escaped America - and Philpott's near imprisonment for libel - by the skin of their teeth. They return to Laurence's home town of Helston, Cornwall, in the hope of rest and recuperation, but instead find themselves in the middle of a tumultuous election that has the inhabitants of the town at one another's throats.

Only two men may vote in this rotten borough, and when one of them dies in suspicious circumstances, Laurence is ordered to investigate on behalf of the town's patron, his old master the Duke of Leeds. But it is no easy matter, thanks to the machinations of the rival political factions, not to mention the riotous performances of Toby the Sapient Hog.

Then the second elector is poisoned and suspicion turns on the town doctor, the gentle Pythagoras Jago, Laurence's own cousin. Suddenly Laurence finds himself ensnared in generations of bad blood and petty rivalries, with his cousin's fate in his hands...

"A wonderful and compelling murder mystery" – Louise Fein

"A brilliantly entertaining historical crime caper" – Philippa East

"An elegant, richly detailed, historical joy" – Kate Griffin

Leonora recommends:

For the historical context for the period in general and ⇲ Black Drop (Viper, 2022) in particular, read John Barrell, ⇲ Imagining the King’s Death: Figurative Treason, Fantasies of Regicide, 1793-1796 (Oxford University Press, 2000)

Patrick O’Brian’s ⇲ Aubrey/Maturin (HarperCollins) series of twenty novels written between 1969 and 1999 were a profound influence on ⇲ Blue Water (Viper, 2023) and I can’t recommend them highly enough as the most enjoyable of literary immersions!

Finally, for ⇲ Scarlet Town (Viper, 2023), some great novels about elections are:

Anthony Trollope, ⇲ Can You Forgive Her? (2018 edition, E-Artnow)

C. P. Snow, The Masters (Macmillan, 1951)

Robert Harris, ⇲ Conclave (Cornerstone, 2017)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Sophie Portas.