Excerpt: The Clockwork Girl by Anna Mazzola

A story of obsession, illusion and the price of freedom

Paris 1750. In the midst of winter, as birds fall frozen from the sky, Madeleine, a new maid, arrives at the home of a celebrated clockmaker and his clever, unworldly daughter. But rumours are stirring that the clockmaker’s uncanny mechanical creations – bejewelled birds, silver spiders – are more than mere automata. Madeleine is hiding a dark past, and a dangerous purpose: to discover the truth of the clockmaker’s experiments.

Meanwhile, in the streets, children are quietly disappearing. Madeleine comes to fear that she has stumbled upon a greater conspiracy. One which might reach to the heart of Versailles itself.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Historie foreword by Anna Mazzola

The Clockwork Girl is a mystery story with a sprinkling of magic set amid the glitter and squalor of pre-revolutionary Paris. The novel was inspired partly by my fascination with automata and the uncanny, and partly by the real scandal of the vanishing children of Paris. When boys and girls began to go missing from the streets in 1750, various theories sprung up as to who or what might be taking them. Some believed the police were using them to extract ransom money. Others thought something far darker was at work. It is those myths or urban legends that I worked with in creating my own story, about the value of human life.

The novel tells the story of three extraordinary women who are fighting to escape their fates: Madeleine, a scarred prostitute turned police spy; Veronique, the clever, closeted daughter of the master clockmaker; and Madame de Pompadour, the beautiful, talented and much resented mistress of the unpredictable King of France. As the novel progresses, we move between the all-too human reek of a brothel, the polished strangeness of the clockmaker’s workshop, the shabby grandeur of the old Louvre palace, and the scandalous opulence of Louis XV’s Versailles.

— Anna Mazzola

Paris, 1750

An excerpt from The Clockwork Girl by Anna Mazzola

Madeleine

Today was the day Maman priced up the girls. Best on such days to slip away. That was why Madeleine now walked past the slaughterhouse, where the blood had congealed into a dark gash across the snow and where carcasses hung from hooks, pale arses to the morning sky. In the glassy air her ungloved hands smarted, the skin of her knuckles cracked and raw. Not much of a day to be out for a walk, but damned if she was staying home to listen. Besides, there was something she needed; something that couldn’t wait.

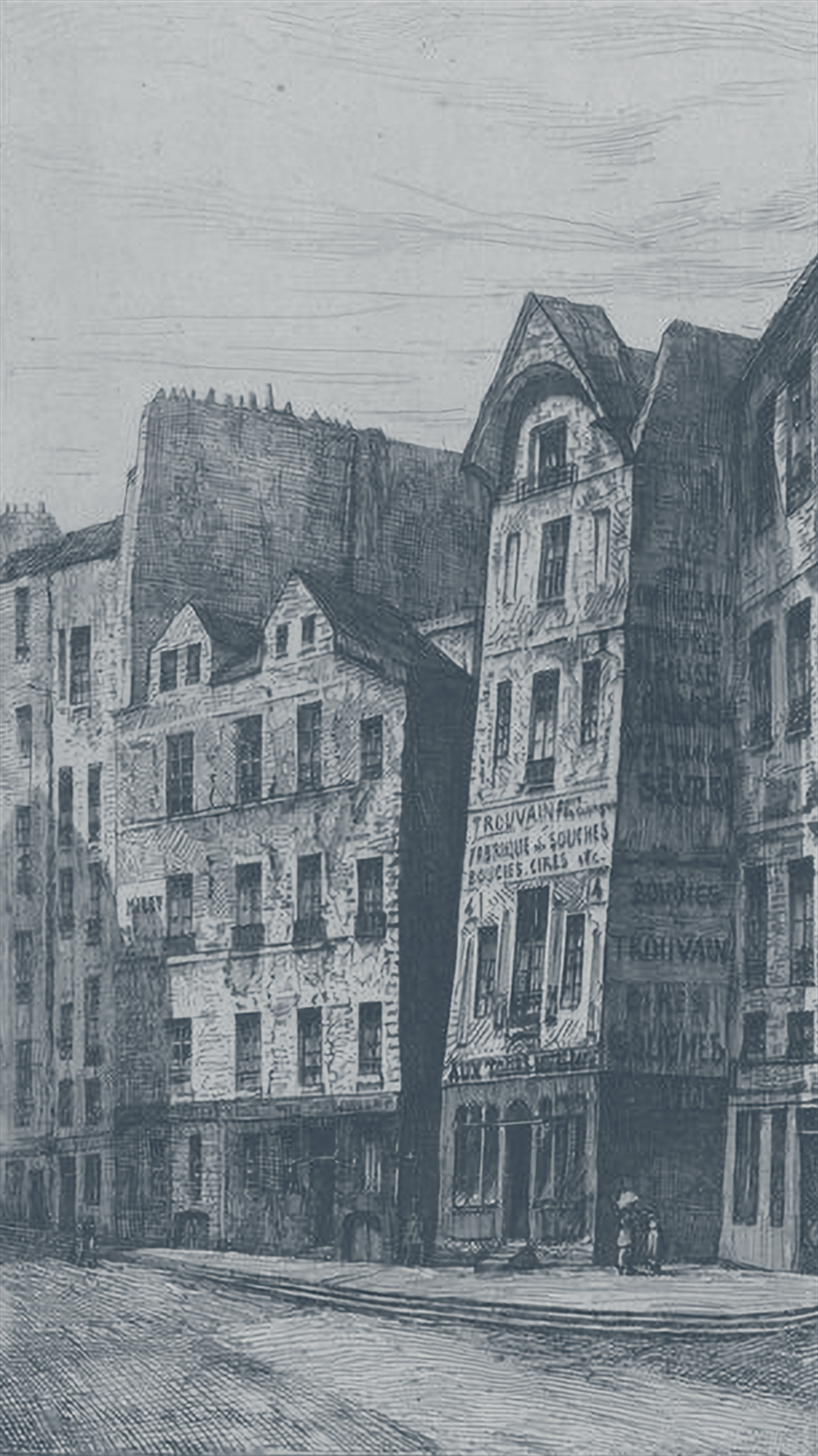

Madeleine turned off the Rue Pavée to enter the labyrinth of the Quartier Montorgueil, the alleys too narrow, the houses too high, so that the sun was kept out and the stench kept in, the streets dark and rank as the devil’s connard. Ancient buildings leaned into one another like crowded teeth, their crumbling brickwork patched together, their windows stuffed with rags. Now and again a face emerged from the shadows: a child, like as not, with the tell-tale features of hunger, generations deep. Better here, though, among the lowest of the low – le bas peuple, as they called them; the slum-dwellers and doorway-lurkers, the homeless and the shoeless – than at Maman’s so-called ‘Academie’, where the monthly inventory would be in full swing.

It was a crying shame, her mother always said, and truly she took no pleasure in it, but she was running a business and human flesh was a damned changeable thing: breasts ripened or withered, diseases took root, skin stretched or pitted, sores filled and burst. Babes – despite a barrage of precautions – were wont to begin and wretched difficult to get out. And once in a while something would happen, just as it had happened to Madeleine, to halve a girl’s value in the space of one day. There’d always be at least one girl – knocked up or knocked down – who would, in Maman’s phrasing, be put out to pasture. Only there was no pasture in the backstreets of Paris. There was a black river of refuse, broken bottles, fish heads. Right now in January there was sleet and snow, blunt figures huddled together in doorways, and the occasional stiffened corpse.

Reaching the Pointe Saint Eustache, Madeleine emerged into the powdery winter sunshine, the air dulled by smoke and ash. She’d left the environs of the poorest of the poor and reached the purlieus of the merely wretched. She skirted the rowdy market of Les Halles and walked south towards the Pont Neuf, sedan chairs keeping the bejewelled and furred bobbing above the thinly-clad poor. As she crossed the Rue Saint-Honoré, a gilded carriage flashed past her, striking sparks from the paving stones, a glimpse of a satin-swathed woman behind the glass. Might be an aristo, might be a femme entretenue in the carriage of her keeper – the only way for a girl to grow rich in Paris was lying on her back.

Finally she was at the river, from where she could see the spires of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame reaching into the winter skies, the single iron spike of the Sainte-Chapelle. Looking only at the skyline, you could imagine that Paris was a rich place, a beautiful place, a city of learning and piety. No doubt it was in part, but not the parts Madeleine knew, for they were the bits Paris kept buttoned. She walked on, along the banks of the dirt-grey Seine, until she reached the apothicaire’s shop, where bottles gleamed in the window like jewels. She hesitated a moment, steeling herself, then pushed at the oaken door.

Inside, the air was spice-scented and warm, though the reception she received was cool. Two women were at the counter, talking intently, glancing at Madeleine and dismissing her as tat without even drawing breath. The apothecary himself was weighing a blue-coloured powder on his great brass scales and took no notice of her at all. As she waited, toes thawing painfully in her boots, Madeleine stared up at the rows and rows of glass jars and porcelain chevrettes lining the shelves. Some of the names were familiar to her: cloves, borage, comfrey, angelica. Some meant little: jalap root, cinchona, sarsaparilla; a box labelled Campeche amber.

‘And she never arrived, would you believe it?’ one of the women was saying to the other. She was, Madeleine thought, one of those sharp-edged women who’ll find the worst in everyone.

‘What happened to her?’

‘Well, no one knows for sure. But there was that travelling fair that upped and moved on the very next day. Makes you wonder, doesn’t it? I wouldn’t be letting my daughter out on her own at that age, of course.’

The apothecary looked up, his eyes resting on Madeleine for a moment like black flies, then darting away. He wrapped the women’s purchases, took payment and stretched his thin lips into a smile. As soon as Madeleine walked forward to the counter, the smile vanished.

‘No improvement?’

‘Very little.’

‘You did as I advised?’

‘I did.’ She paused. ‘Is there something else that might help?’

The man considered her. ‘Possibly, but it’ll cost you.’

Didn’t it always? For an instant she considered pleading with him, telling him of their circumstances, but she knew there was little point. No one gave anything in Paris for free, certainly not to a girl like her.

‘More than last time?’ she asked.

‘I’d say so, yes. The stuff is expensive, brought over from the Americas.’

Madeleine raised her eyebrows. ‘Exotic. I see.’

She watched in silence as he pounded the ingredients in a pestle and mortar, crushing the seeds to dust. A powerful aroma filled the air, nutmeg mixed with something burning and bitter. The apothecary transferred the medicine to a green glass vial and set it down on the counter before her. ‘Two louis, it’s worth.’

Madeleine’s eyes were on his veined white hands. ‘Very well.’ She looked back at the door. No other customer had entered.

The apothecary walked over and turned the sign, indicating the shop was shut.

Madeleine walked back home slowly, her cloak wrapped tightly about her, passing women in great fur mufflers walking tiny dogs on leashes, and servants out on errands, raw-faced in the cold. She made her way up the Rue de la Monnoye, looking into the windows of milliners’ shops filled with feathered hats, like a flock of exotic birds. Is this how her father’s parrots had ended up, she wondered – made into bonnets for the gens de qualité? He’d been a oiseleur, her papa, selling birds and other small animals, from a shop on the Quai de la Mégisserie. After his death, Maman had sold his stock to another trader – cockatoos, finches, white mice and squirrels, all boxed up and passed on quicker than you could say jackanapes. The rent on the shop being long overdue, they’d cleared out quick from the house she’d grown up in and set up in the Rue Thévenot, selling a different kind of bird.

She walked on, past jewellers’ shops glimmering with sapphires and rubies, or paste that looked very much like them. That was the thing with Paris, you had to learn the trick of telling what was real and what was false. Gems, hair, cleavages, characters – all could be easily faked. Smallpox taken your eyebrows, Madame? Buy this pair of finest mouse fur. Lost your teeth in a brawl, Monsieur? Have a set drawn from another’s grave. Madeleine could see her breath, a puff of white in the icy air, and her hands were now almost numb. Still she didn’t hurry, for she doubted her mother would be done. Genevieve Chastel – ‘Maman’ to the girls – was nothing if not rigorous.

Some of the ones her mother put out would survive, at least for a time, on the backstreets as filles publiques, the lowest in the pecking order of the many who sold sex in the demi monde, running from the femmes de terrain in the public gardens to the bejewelled mistresses of Versailles. Some of Maman’s girls would die nearby in the filth of the Hôtel Dieu, the hospital God had abandoned long ago. Some would be swept by the police into the countryside. There was little point in thinking of it. If she did, she’d only be reminded of how chancy her own state was, how close she was to the brink. She’d no money of her own, no property, no references. If Maman put her out, she’d be on the streets like the rest of them, more mutton for the Paris pot. That was why it was best never to get too close to the other girls. She tended to them as required – brushing and plaiting their hair, pinning them into their dresses, changing their spunk-stained sheets. But there was no value in trying to help them. She had to focus on saving herself and, more importantly, Émile.

‘Aren’t you a cold one?’ her elder sister, Coraline, had said earlier as she headed for the door. Rich, of course, coming from her.

Well, better to be hardened to a chip of jade than crushed, like the others, to dust.

It was past ten o’clock by the time Madeleine turned into the Rue Thévenot, her home since the tender age of twelve. (Tender, in fact, as a prime cut of beef, and sold for not much more.) The narrow street had been swallowed in shadow, all the better to hide the flaking house-fronts and rubbish-strewn ground. As she passed the vinegar-maker’s, the tang of fermenting wine in the air, her eyes sought out the hunched figure of the girl who’d been living in a doorway these past few weeks. Sure enough, there she was, a man’s coat tied about her with string, a coat that’d been perhaps her father’s or brother’s. Madeleine hadn’t asked, had barely spoken to her. The girl’s story would be much the same as all the other orphans and outcasts living in the city’s stinking streets – disease, debts, liquor, death – and Madeleine had no wish to hear it.

‘Demoiselle?’ the girl stretched out her grubby hand.

Giving a tight nod, Madeleine reached into her pocket and took out the last few sous she had. Not enough for much, but maybe enough for some soup.

‘Thank you. You’re very kind.’

Very stupid, more like. Madeleine thought to herself as she continued up the road. The girl wouldn’t survive a winter like this, so why prolong her suffering? She stopped. An icy breath seemed to touch the back of her neck. But when Madeleine turned she saw only a thin black cat, its eyes glinting in the shadows.

The Acadamie

The Academie, as Maman called it, comprised the middle two floors of a tall, soot-stained building at the end of the street, bowed and blackened like a filthy finger, beckoning customers to the door. There was a staircase at the back by which the punters could enter and, though there was no sign marking the brothel, the place could be recognised at ten paces by its customers’ distinctive stink. The men marked their territory like tomcats and the steps reeked with accumulated piss. Breathing only through her mouth, Madeleine entered the house, shut the door quietly, took off her muddy boots, and crept up the carpeted stairs. Behind a closed door she could hear a girl weeping and she walked quickly and noiselessly past.

‘Where’ve you been?’ A small figure jumped up as she reached the landing: her nephew Émile, face unwashed, hair unbrushed. ‘You’ve been hours and I’m hungry.’

Madeleine stared at his grimy face with a mixture of love and annoyance. ‘Did no one think to give you breakfast? No, of course they didn’t. Why feed an eight-year-old boy? Go clean your face and hands, you little horror, and I’ll get us both something to eat.’

The house was quiet, she noticed, as she warmed milk in a pan and sliced a loaf of bread; a strained sort of silence, of held-in anger and whispers behind bolted doors.

They made faces at each other as they sat at their breakfast, Émile snorting milk back into his bowl at Madeleine’s impression of Grandmaman. After a minute, however, he grew serious. ‘There’s two girls gone this time. Odile and Lisette.’

‘That so?’ No surprises there. Odile hadn’t had her courses these past two months and Lisette had for days been wearing lace gloves to hide the familiar rash of the pox. Madeleine stared at her own hands, the nails broken, the knuckles red, and tried not to think of their faces.

Émile’s body was for several seconds wracked with coughing. She rubbed his back; thought of the medicine bottle, the man’s cold, insistent fingers.

‘Will she get rid of me, Madou?’ he said, wiping his mouth.

‘Will she make me go one day too?’ It was a question he asked Madeleine often, and her answers were always the same.

‘No, of course not, mon petit. You’re her grandson.’ Not that that meant much to her mother who, above all things, was a cold and clear-eyed businesswoman. ‘And you’re a useful little machine, aren’t you? Always running errands and helping out.’

Mostly Émile was tasked with trailing punters back to their homes. There were plenty of slippery coves who gave a false name and false address, and it was in Maman’s interests to follow them to their lairs. If a cull didn’t pay, or if a cull caused problems, she needed to know where to find him. It was dangerous work for a boy like Émile, though. Dangerous, in truth, for anyone.

‘And she won’t turn you out, will she, Madou? She won’t ever make you leave?’

Madeleine tensed and smiled to conceal it. ‘Like I always say, Émile: I don’t think so. I have my uses too.’ Skivvy, teacher, voyeur, whore. But with Maman, there were no guarantees.

Footsteps in the hallway and then the door opened a crack, Coraline’s painted face appearing from behind it. ‘There you are, Madou. Maman wants you in the parlour. Now.’ Madeleine’s heart plunged. ‘Why?’

‘Just come, will you? Quick.’

Madeleine felt Émile’s eyes on her face, felt his fear in her own chest, and winked at him. ‘Don’t worry, mon petit. You know what she’s like – probably wants me to massage her gnarly old feet. You finish eating your breakfast.’

But as she walked down the corridor, smoothing down her skirts, fear corkscrewed up through her chest; perhaps the inventory wasn’t finished at all and she was the next to be priced ■

The Clockwork Girl

Orion Publishing Co, 3 March 2022

RRP: £14.99 | 368 pages | ISBN: 978-1398703780

Paris, 1750.

In the midst of an icy winter, as birds fall frozen from the sky, chambermaid Madeleine Chastel arrives at the home of the city's celebrated clockmaker and his clever, unworldly daughter.

Madeleine is hiding a dark past, and a dangerous purpose: to discover the truth of the clockmaker's experiments and record his every move, in exchange for her own chance of freedom.

For as children quietly vanish from the Parisian streets, rumours are swirling that the clockmaker's intricate mechanical creations, bejewelled birds and silver spiders, are more than they seem.

And soon Madeleine fears that she has stumbled upon an even greater conspiracy. One which might reach to the very heart of Versailles...

A intoxicating story of obsession, illusion and the price of freedom.

"Historical fiction with a fantastical twist, done with verve and skill" – Ian Rankin

"An atmospheric and constantly surprising thriller" – Sunday Times

"A deliciously dark historical novel of thrilling originality" – Essie Fox

Anna recommends:

The Vanishing Children of Paris: Rumour and Politics before the French Revolution by Arlette Farge, Jacques Revel and Claudia Mieville (Harvard University Press, 1993)

"The authors use the scandal of the vanishing children to explore the power of rumour, crowd psychology and the corruption of the police in Paris."

⇲ Living Dolls: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life by Gaby Woods (Faber, 2003)

"A fascinating history of humanity's obsession with moving dolls, automata and intelligent machines."

⇲ Little by Edward Carey (Gallic Books, 2019)

"Strange and marvellous. Set in 18th Century Paris, Little is the brilliantly-illustrated reimagining of the life of the woman who would become Madame Tussaud."

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.