Excerpt: The Dangerous Kingdom of Love by Neil Blackmore

Those who understand desire win. And I intend to win.

Francis Bacon, philosopher, politician, writer, is an outsider at the court of King James I. He is clever but not aristocratic, has ambition but no money. So when his political enemies form a deadly alliance against him, centred around the King’s poisonous lover Robert Carr, Bacon has no choice but to fight for his survival.

Together with the neglected Queen, Bacon resolves to find a beguiling young man who can supplant Carr in the King’s bed. But as he soon discovers, desire is not something that can be controlled.

Bold, irreverent and utterly original, The Dangerous Kingdom of Love is a darkly witty satire about power, and a moving queer love story that resonates through time.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Neil Blackmore

In my new novel, ⇲ The Dangerous Kingdom of Love, the 17th century philosopher and politician Francis Bacon, “the cleverest man in England,” is trying to get rid of his enemies, led by James I’s favourite Robert Carr. To do this, he comes up with a plan with James’s queen to replace Carr with a new, more malleable male favourite. But the handsome young man he meets proves less malleable – and more intriguing – than Bacon expects.

The book is narrated by Bacon in a witty, ironic, but politically merciless voice that weaves his plotting – and his world-changing ideas – through Jacobean London’s theatres and taverns, palaces and parklands, and one hell of a lot of intrigue. It is based in the true events of the Overbury affair, a murder scandal at rocked Stuart England, which implicated the very highest levels of society in deadly wars of poison, duplicity and lust.

People’s real motivations are often hidden in the story, but the true secret is that of gay life of the time. So, the King’s relationships with these handsome young men are literally the worst-kept secret in Europe, but Bacon’s own desires (and those of men like him) could be used to destroy him. The book is witty but brutal, historical but modern – and, hopefully, very funny. One reader brilliantly described it as “Hilary Mantel on acid” but it is also a story about love, connection and sex, and how we deceive ourselves in pursuing them.

— Neil Blackmore

England, Spring 1613

An abridged excerpt from The Dangerous Kingdom of Love by Neil Blackmore

On the Subject of Power and a a Porkchop

There is a myth that power destroys people, that it makes them unhappy. This is a lie. This lie is told by poets and philosophers, priests and preachers, who do not want you to have power but want to have it for themselves. But these poets, philosophers, priests and preachers know that they will never obtain power, and so they sit, curdled with bitterness and failure, making pronouncements such as this.

Wait a moment, Bacon, you might say, you are a philosopher, and maybe a kind of poet, perhaps not a priest but, in a funny kind of way, a preacher. You are trying to deceive me! But I am not, for I am going to tell you the truth. Power does not make people unhappy – not one tiny bit. Think about it. If power made people unhappy, they would flee from it in horror and pain. But do they? Do they?

Exactly. Power makes men happier than anything else: more than love, than God, than their children. They do not admit this, but what men - and women - admit about their ambitions is worth nothing. People lie all the time, especially to themselves. What power does is put them in control, of their own lives and of others'. That is what makes them happy. That, beyond money, and palaces, and fancy friends, is why they want power in the first place.

Leaving Theobalds, I looked up at the same moon that had illuminated the cruel, exquisite beauty of Robert Carr. Now black clouds were rolling across it, the darkness opening and closing, revealing the moon as a white rose in midnight blue. North of London, apart from the odd tiny village like Islington or Hampstead, the landscape is still all woodland or heath. At night, it is perilous to ride out there. There are thieves and bandits everywhere in the English countryside, so known for its violence. Keep your head down, ride fast, and look like you have nothing worth stealing. That night, I covered my head in my customary dun-brown hat and wrapped my body in a huge black felt shawl; my clothes are modest even if my ambitions are not. My horse flew past the dark, wooded outskirts of Enfield Palace, the empty pastures of Tottenham, their shepherds long since in their beds, up and down the Stamford Hill and on through the open marshes of Hackney, where the bodies of the robbed-and-murdered litter the swamps that drain before the city starts.

As I rode, I was consumed by thoughts of how I had started the day in such hopes – of my glorious advancement – and ended it in the bitter reality of the turning of the game. Now I saw not my advantages but those of the new Howard-Carr alliance: of the unlikely son-and father-in-law, Carr and Suffolk, and Carr's lover, the King, and Suffolk's friend, Southampton. Where did I get a look in there? The King trusted me and liked my work, but these things are easily changed. Words whispered in that drunkard's ear, week after week, month after month, will easily sway his mind. The King is a fool, a child, and he is in love – the worst possible combination.

So, the next year would play out like this: first the alliance forms, then it closes around the King, whispering in his ear of my plots, disloyalties and corruptions, and when he says, 'What? Good old Bacon?' they whisper yes, and yes, and yes again, until he starts to believe their lies. After that, it is only a matter of time until the King wants to believe the worst of me. Oh, the universe likes a joke – and the best ones are at my expense!

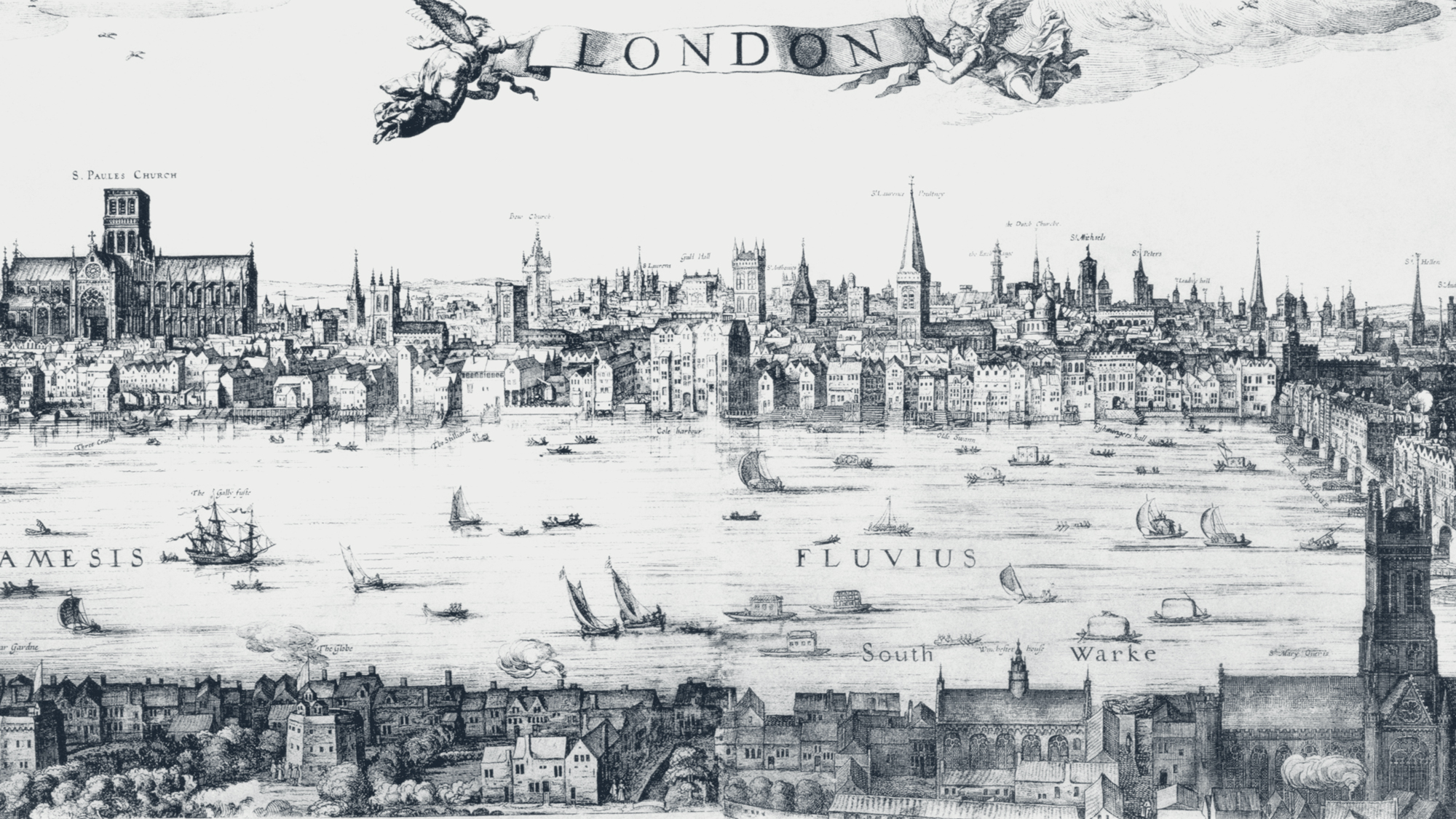

Out in the countryside, I hardly saw a soul. Where the pastures and enclosed farms of Clerkenwell start to break up into hamlets, the city truly begins. I heard my horse's hooves echoing on the cobbled lanes so narrow that neighbours on either side could open their windows and catch hands. I only stopped at my longtime lodgings at Grays Inn just to stable my horse, wash my face and change my sweat-damp shirt. I had arranged to meet my friend, the playwright Ben Jonson, and his friend, Shakespeare, another playwright, to drink and talk. Grays Inn is at the very edge of London, at its north-eastern fringe, but Jonson and Shakespeare always want to meet in Southwark. They never want to drink in London, because the true fun lies south of the river.

Southwark is a temptation that Londoners can never resist. People talk of London as one city but in fact, it is three. Yes, three cities splay out from the river, quite separate in history and identity, and never touching. London, the old Roman city, is where trade – the most important thing in England, the foundation of its power – is conducted. A country road leads the mile or two down to Westminster, the medieval village of palaces, where the only business done is government. Open water cuts off both from Southwark, the only part on the south side of the Thames. There, other kinds of business are conducted: drinking, gambling, whoring, fighting. And the theatre. Southwark, then, is the city of pleasure, or more specifically, sin. So I had to go on to the George Inn, where the two playwrights would be greeted as great heroes, and people would applaud their appearance. The people there would not notice mine.

But before getting there, you have to cross the thicket of bodies on the Bridge. The carriage I took got stuck in the throng of other carriages and stalls and people pushing this way and that, in and out the shops and houses along the Bridge. Waiting for the traffic to move, I looked out downriver, the water burnished with lamps on barges, illuminating the Tower beyond. I always shiver a little when I see it, this place of torture and death where the King joked he was not sending me – yet. Every courtier fears that one day he will end up there, and that fear is justified. Spies, Catholics, suspected Catholics, royal cousins, royal wives, Irish princes, Guy Fawkes and all his friends, even the Earl of Southampton (more on that presently) have all languished there. On that very night, Sir Walter Raleigh himself had already been there ten years. Huge, black and impregnable, entering the Tower means there is always the chance you will never leave it again. And so it is a fourth city: the city of destruction. The carriage started to move, and my dark thoughts shifted. There was Southwark – and its fun – ahead.

Arriving at the George, inside the fires were roaring. Too many bodies had been sitting for too long, afraid of the cold night, so you could cut the hot, stale air as you entered. Even worse, everyone likes to smoke tobacco these days. A thick cloudy fug filled the space, and the sound of coughing. A grey tinge on the tongue. Everyone says how good tobacco is for them, that it 'openeth up all the pores and passageways', and that the American peoples all live to a great age as a result. But if I was to apply my rudimentary science, I would ask you: Then why the hell are you coughing? Above the din, I heard Jonson's voice calling, to me: Well, if it isn't Old Porkchop, back from all his fancy friends!' He beckoned me over.

I cannot tell you how much I love Ben Jonson. He is the funniest person I know and the most honest. We met when he was poor, so much poorer than me that I gave him money: Imagine! Me, giving someone else money, that's how poor he was! He started calling me 'Porkchop' on the second day of our acquaintance, and never called me Bacon ever again. I would miss it, if he stopped calling me it now: Sometimes, I think Jonson is the only person in the world who truly likes me. I mean, there are those who find my company – or my ideas – interesting or entertaining. And there are even those who might think of me as very ‘useful' to know, but I think Jonson alone is truly my friend. I do not mind, I tell myself, but know that if I do not, why; then, do I cherish this one friendship so?

Jonson was over in his favourite spot, a cubby-hole next to the back door, where he could hide from, or regale, his admirers as he preferred. Next to him, I saw the shiny top of Shakespeare's bald head. Even though I knew he was going to be there, still I groaned inside. I shall tell you this plainly: I do not like Shakespeare. He has that revolting aspect of the successful writer who asks you – with a genuine, wide-eyed curiosity – why not try to be successful? Why not try earning some money, Bacon? You know, for a nice change? He says things he wants you to believe are pleasant, when in fact they are noxious. (I suspect that he knows you know that, too.)

As I arrived at my seat, I could see they had been drinking a while. Their eyes were woozily, happily pink. 'Ale!' Jonson yelled to the bar. ‘Ale for our mighty friend from court.’

I shushed him. ‘People will think I am rich if you keep saying that, and they'll rob me when I leave.'

‘Ha!’ Jonson croaked. No one will think you rich, Porkchop. Not with that fucking hat.’ He laughed and I bowed ironically, removing said hat from my head.

How was court?' Shakespeare asked.

‘I saw your patron, Southampton, there,' I said.

‘Did he enquire after me?’ he asked greedily. So I smiled at him, with the edge of curdled cream. Seeing that, his tone changed, into its natural meanness. I am sure he did not ask after you.'

At last, I shall explain why Southampton hates me. Our enmity – or rather, his for me – is old now, having begun almost fifteen years ago, before the King came down from Scotland. The Earl of Essex – the last Earl, the father of Frances Howard's unpenetrating husband – was the old Queen's final favourite. At that time, I went into great disfavour with the old girl, over a minor matter of law. (She was one of those bosses never more furious than over minor matters.) To try to find my way back in – for a person in politics cannot prosper without royal favour – I befriended Essex. The Queen, who was in love with him, was persuaded to admit my presence again. Then disaster struck. Essex had been sent by Queen Elizabeth to quell a revolt in Ireland but made a godawful mess of the whole thing and came back in disgrace. Among his best friends was none other than the Earl of Southampton, then very young and even more of a hothead than today. There was talk that Essex, outraged by his entirely deserved disgrace, was going to launch a revolt against the Queen. Essex gave me assurances of his loyalty, and I told her the same. A week later, he launched a coup, which failed. Essex and Southampton were both arrested.

In that kind of mental game of which she was so fond, the old Queen forced me to write the official report of events, in which I was to damn Essex. But she found my analysis too fair and angrily rewrote the report herself. It condemned her former favourite, although he had already gone to the block; it was more of a massaging of history than anything else. Southampton was sentenced to life in the Tower. It was widely whispered that I had betrayed my friends to curry favour with the old Queen. This absolutely was not true. I am guilty of many toadying things, but I was not guilty of destroying Essex. But people bet over things at court – you have to – or, at least, I thought they had ■

His third novel, ⇲ The Intoxicating Mr Lavelle, was shortlisted for the Polari Prize for LGBTQ+ Fiction. ⇲ The Dangerous Kingdom of Love, his most recent title, was memorably described as 'Hilary Mantel on acid' and chosen as one of The Times' Best Historical Fiction Novels. He lives in London.

The Dangerous Kingdom of Love

Cornerstone, 15 July 2021

RRP: £16.99 | 352 pages | ISBN: 978-1786332677

The kingdom of love is a frightening place. A dangerous place. What kind of fool wants to live there?

How have I, Francis Bacon, well-known as the cleverest man in England, been caught in this trap? For years I survived the brutal games of the English court, driven by the whims of the idiot King James I - and finally, I was winning. Forget what my friends Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare say about love. I had that which men truly crave above all else: power.

But now, at the moment of my greatest success, a deadly alliance of my enemies has begun closing in on me. Led by the King's beautiful and poisonous lover Carr, this new alliance threatens to turn our foolish King against me, so that I may rot in the Tower.

I refuse to go down without a fight. I have concocted a brilliant new plan: I will find my own beguiling young man and supplant Carr in the King's bed, and take power for myself. All I need to do is find him, my beautiful and mysterious creature, my perfect chess move.

In the dangerous kingdom of love, those who understand desire win. And I intend to win, at all costs.

"Expect much enjoyment from this clever and unusual novel" – The Times, Historical Fiction Book of the Month

"An entertaining and often very funny read with something to say about both the love of power and the power of love" – Sunday Times

"Neil Blackmore writes with a fizzy wit that bounds his characters off the page" – Ben Aldridge

Neil recommends:

⇲ The Intoxicating Mr Lavelle by Neil Blackmore (Cornerstone, 2021)

My last novel was an 18th century romp around Europe’s Grand Tour, showing queer voices discussing art, philosophy and how to destroy your social enemies.

⇲ New Atlantis by Francis Bacon originally published 1627 (Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Bacon changed how we think about politics, science, travel and philosophy. His only novel, which tells of a journey to an Atlantis-like kingdom, captures much of his revolutionary thinking.

⇲ A Dead Man In Deptford by Anthony Burgess (Vintage Publishing, 2010)

A direct influence on my novel, a brilliantly rendered, cleverly murderous trawl around Elizabethan London, as Christopher Marlowe faces death.

⇲ I, Tituba Black Witch of Salem by Maryse Condé (University of Virginia Press, 2009)

Condé astonishing retelling of the Salem Witch Trials casts Tituba not simply as victim but as resourceful, complicated and sometimes determined on revenge.

⇲ Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell (Headline Publishing Group, 2021)

In my novel, Shakespeare is a dislikable sneak, but in O’Farrell’s bestseller, he is an absent, self-involved husband whose wife is the fulcrum of a then-everyday tragedy: a child’s death.

⇲ The Revolutions Trilogy (Kepler/Copernicus/The Newton Letter) by John Banville (Pan Macmillan, 2010)

More scientific revolutionaries turned into novelistic heroes in these three slim Banville novels.

⇲ Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel (HarperCollins, 2019)

The daddy-novel of gnawing, deadly court intrigue, Tudor-style.

⇲ Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (Penguin Books, 2006)

Achebe is the master of telling historical stories from the other side, and this is, his most famous novel, is a beguiling, complex glimpse of the moment before colonialism hit historical Nigeria.

⇲ Havoc, In Its Third Year by Ronan Bennett (Simon & Schuster, 2007)

Bennett’s disturbing novel about a nation’s descent into the chaos of the English Civil War tells of the era’s “bitter times and the world…divided in two.”

⇲ Civilizations by Laurent Binet (Vintage Publishing, 2022)

Binet’s most recent novel shows you how to write modern, counterfactual “historical fiction” where the Incas invade Renaissance Europe, not the other way round.

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Marie-Louise Patton at PenguinRandomHouse.