Excerpt: The Hated Cage by Nicholas Guyatt

An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison

The War of 1812 – the last time Britain and America went to war with each other. British redcoats torch the White House and six thousand American sailors languish in the world’s largest prisoner-of-war camp, Dartmoor.

Known as the ‘hated cage’, Dartmoor wasn’t a place you’d expect to be full of life and invention. Yet prisoners taught each other foreign languages and science, put on plays and staged boxing matches. Drawing on meticulous research, The Hated Cage documents the extraordinary communities these men built within the prison – and the terrible massacre that destroyed these worlds.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Nicholas Guyatt

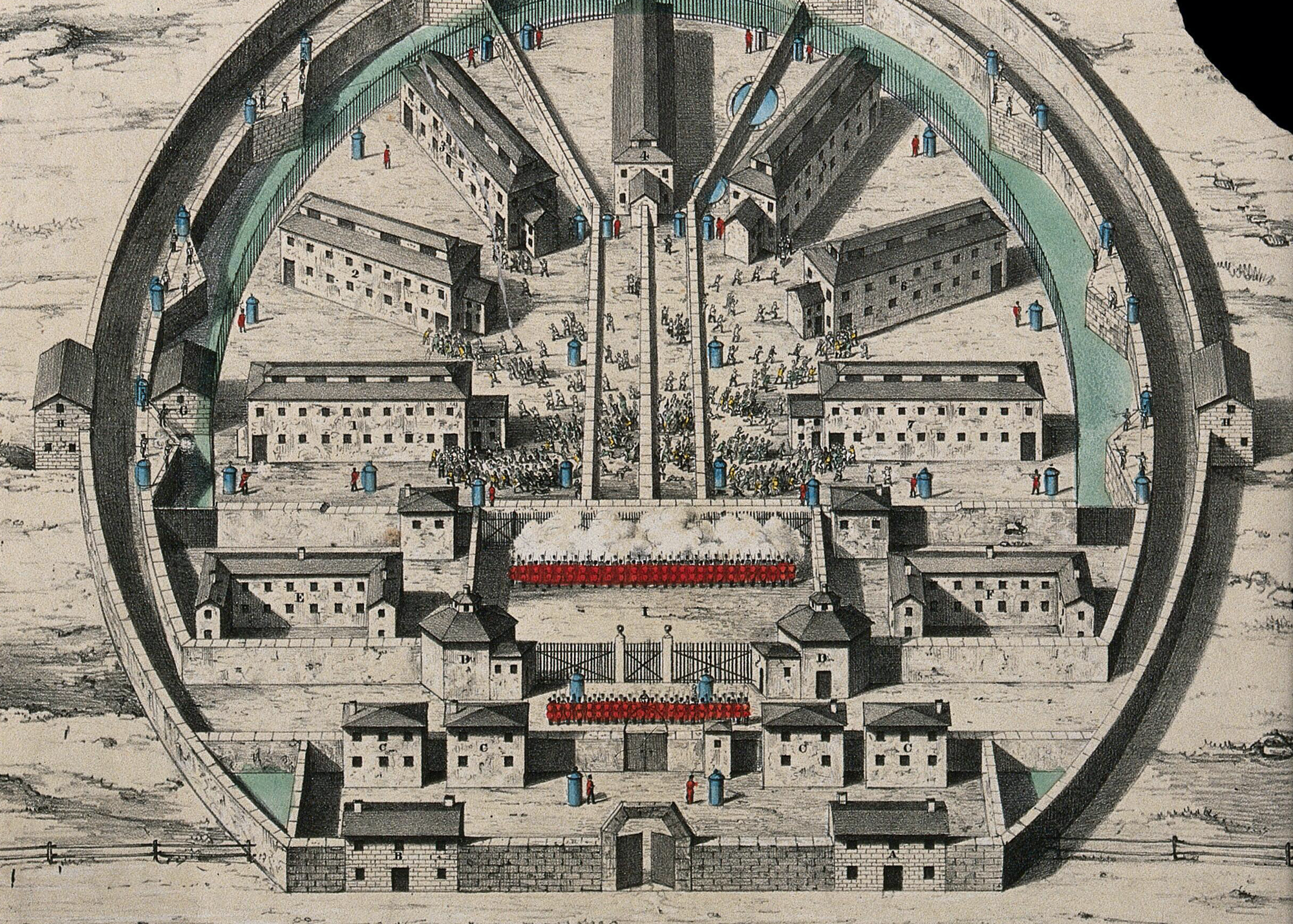

Most people in the UK have heard of Dartmoor Prison: we know it as a grim facility in the middle of nowhere, a place of hardened criminals and bleak prospects for escape. Some might even know that Dartmoor was a destination for political prisoners, from Irish Republicans to conscientious objectors. But very few people are aware that Dartmoor began life in 1809 as a prisoner-of-war facility, and that before the circular prison acquired cells and convicts it housed around twenty-thousand French and American captives from the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812.

In my new book ⇲ The Hated Cage, I try to explain how 6500 Americans fell into the grim prison blocks of Dartmoor between 1813 and 1815, and I recount the terrible massacre which claimed the lives of nine of them on 6th April 1815. But in the excerpt below I address a more basic question: why did Britain build a huge temporary prison out of granite? The answer lies in the strange vision of Dartmoor’s eccentric founder, Thomas Tyrwhitt, and in the undue influence of his sponsor, the Prince Regent. So much of the story of Dartmoor seems fantastical, and yet it’s all true.

— Nicholas Guyatt

The World’s Biggest Prison in the Middle of Nowhere

An excerpt from The Hated Cage by Nicholas Guyatt

At some point in the spring of 1805, Thomas Tyrwhitt decided to build the world’s biggest prison in the middle of nowhere. Tyrwhitt’s father was a clergyman, though a very rich one: Thomas was sent to Eton and then to Oxford. He struggled at school, where the other boys called him ‘Clod Tyrwhitt’, and wasn’t much happier at Oxford. His diminutive stature and romantic disappointments produced another cruel nickname—‘the Squab Cupid’—to accompany his modest degree. But at Christ Church, the largest of the Oxford colleges, Tyrwhitt made a connection that would change his life. The dean of the college introduced him to George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales, an almost exact contemporary. The two became friends, and Tyrwhitt was soon working for the future George IV. In 1795, he was appointed the prince’s private secretary, and for most of the next two decades he filled a variety of roles while the prince waited (and waited) to be king. He also helped George to administer one of his many distractions, the Duchy of Cornwall. A vast tract of land and property concentrated in Devon and Cornwall, the duchy was first given to the Prince of Wales in the fourteenth century and even today brings the heir to the throne an income of more than £20 million every year. George gifted Tyrwhitt two and a half thousand acres on Dartmoor, within the largest tract of duchy land, and encouraged him to think big. Surely, the barren region could be recovered for civilization and industry if only a visionary would champion its cause? Tyrwhitt gratefully built a house, Tor Royal, in the splendid isolation of the moor. If everything went to plan, he would soon have plenty of company.

Working for the Prince of Wales was a challenging job. Great wealth and power—or, at least, the expectation of power—did not instil great responsibility. George’s drinking and affairs alienated him from his father, and the king’s frustrating longevity alienated him from his son. George III’s apparent madness was first diagnosed in 1788, but it would be more than two decades before his son assumed the title and authority of Prince Regent. For much of the intervening time, the younger George drowned his disappointments in alcohol. (He drank so much on his wedding night in 1795 that he fell into a fireplace, to the relief of his already long-suffering wife.) Thomas Tyrwhitt was an unusually loyal servant during those years, perhaps because his upbringing had inured him to abuse. When George and other members of the royal family mocked him for his height—they called him ‘the twenty-third of June’, the shortest night of the year—he smiled and carried on. In turn, George was happy to support and even indulge Tyrwhitt in their pet project: the transformation of Dartmoor’s lifeless expanse into a thriving region of farmers, labourers, and artisans.

George even made Tyrwhitt a member of Parliament, shuffling him through a number of ‘rotten boroughs’ (where the powerful could win election without opponents or voters) until Tyrwhitt became MP for Plymouth, the Royal Navy’s centre of operations on Britain’s south coast. Dividing his time between Dartmoor and London, Tyrwhitt built a pub and a mill near his new house, along with a road to bring visitors from beyond the moor. He carefully laid out crops in his grounds, hoping to prove that flax and wheat could thrive on Dartmoor despite the fog and solitude. Then, in 1805, he learned that the government wanted to build a new facility for the vast number of French prisoners piling up in hulks at Plymouth and at Chatham near London. Tyrwhitt talked to his friends in the Admiralty, and almost certainly to his boss, who had visited him at Tor Royal on a number of occasions (so often, in fact, that the locals insisted that George had taken a mistress there). By the summer of 1805, an architect had been agreed and Tyrwhitt was elated. What better way to advance his dream for Dartmoor than to put a gigantic prison at its centre?

Tyrwhitt’s outlandish proposal was rooted in two developments: the codification of the laws of war, and the rise of the modern prison. In the final months of the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin reminded a British friend that it had been standard practice just a few centuries earlier for states to execute prisoners of war. Victorious armies had later progressed to enslaving rather than murdering their captives. Now, in the enlightened eighteenth century, a new body of international law mandated that prisoners be treated humanely and exchanged as quickly as possible. Franklin’s pride in this process of ‘humanizing by degrees’ was not entirely justified: POWs in the second half of the eighteenth century could still meet with medieval treatment, though in theory warring powers had three attractive options for disposing of prisoners. They could exchange them like-for-like, a system which relied on each side taking an equal number of prisoners. They could ransom them, agreeing on a fee to secure the return of a given number of prisoners. Or they could parole them, a system usually applied to civilians and to officers. Parole originally meant that a prisoner would be freed and sent home after swearing an oath not to take up arms again in the conflict; by the end of the eighteenth century, it meant instead that a prisoner would be placed in private accommodation in a town or village under the equivalent of house arrest rather than in the grim confines of a war prison.

If these systems worked properly, every captive would be speedily released. But during Britain’s endless battles with France (and the Revolutionary War with the United States), a number of problems became apparent. Thanks to its naval superiority, Britain quickly amassed a huge surplus of prisoners. Exchanges broke down and, with wars dragging on for years, British officials scrambled to repurpose buildings to accommodate a large and embarrassingly permanent POW population. The perpetual fallback option was to hold prisoners in ships—originally working vessels, though eventually retired ‘hulks’—which was both expensive and harmful to the wellbeing of prisoners. During the American Revolution, British prison ships in New York served as perfect incubators for smallpox: their mortality rate of over 40 percent was roughly ten times that of land-based prisons. The same grim ratio applied to the hulks that dotted the British coastline during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. With Britain styling itself as enlightened and benevolent in its conduct of war, keeping prisoners out of the hulks became an urgent necessity.

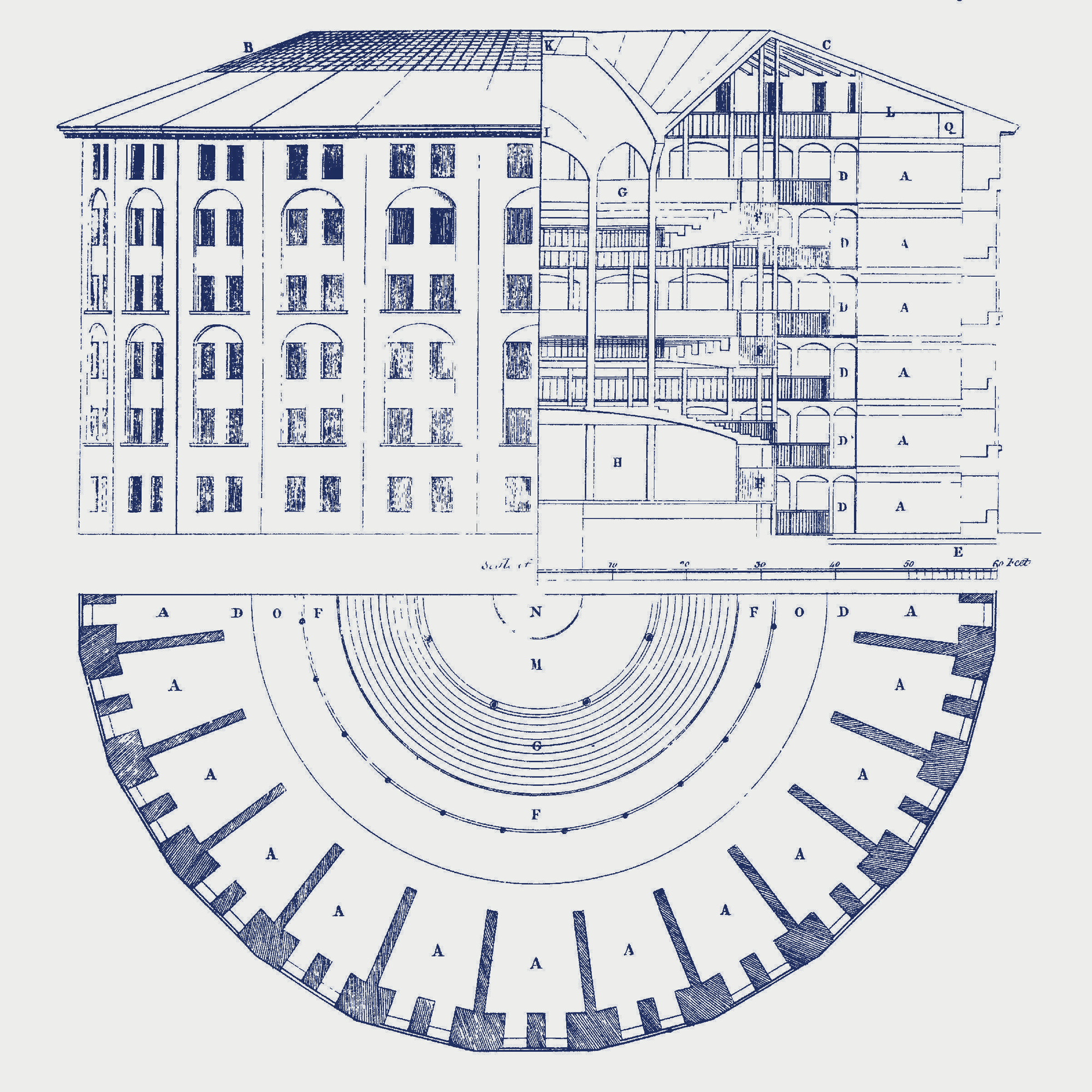

The other development that shaped Tyrwhitt’s thinking about Dartmoor was the rise of the modern prison. Given how indelible they seem in our own era, it’s surprising to learn that prisons are a relatively recent invention. Before the American Revolution, most convicted criminals in Britain were banished to the North American colonies. Although debtors could be imprisoned indefinitely, criminals were subject to execution, transportation, or some form of public humiliation. The Declaration of Independence cut off the flow of felons to North America, creating a backlog of prisoners in the British justice system. Australia would later provide a new outlet for criminals, but British reformers used the disruptions of the Revolutionary War to advance a radical new idea: instead of simply holding prisoners before their trials, prisons might themselves serve both to punish and rehabilitate wrongdoers.

The greatest prison theorist of the eighteenth century was John Howard, a British reformer who spent the 1770s and 1780s on an endless tour of jails in Britain and overseas. Howard was mostly appalled by what he found: crumbling and unsanitary facilities, hollow-eyed prisoners, avaricious jailers who supplemented their income by allowing taprooms, billiard tables, gambling, and sex work in their jails. ‘A prison mends no morals,’ Howard sadly observed at the end of his tour. But it didn’t have to be this way. With the proper resources and thinking, prisons might turn back the tide of criminality and redeem society as surely as individuals. Howard led a public crusade that insisted on custodial sentences for all but the most terrible crimes, to be served in purpose-built prisons. His vision inspired architects, politicians, philanthropists, urban planners, and a host of others in late-eighteenth-century Britain, and animated a parallel prison reform movement in the new United States.

At first glance Howard’s crusade had little to do with Dartmoor. A war prison, after all, was intended to secure combatants rather than rehabilitate criminals. But Thomas Tyrwhitt knew that eventually Britain and France would stop fighting, and that Dartmoor would need an engine of development when peace broke out. Given the sunny thinking of reformers about the societal benefits of a modern prison, he assumed that Dartmoor would welcome criminals in place of sailors at the war’s end. The slippage between a war prison and a criminal facility brought dangers as well as risks, however. John Howard had originally become interested in prison reform after being captured by the French on a visit to Portugal during the Seven Years’ War. ‘What I suffered on this occasion,’ he wrote in his most famous tract, ‘increased my sympathy with the unhappy people whose case is the subject of this book.’ Howard’s acknowledgement that ‘a prison mends no morals’ spurred his attempts to create new and more humane forms of incarceration, but it also offered a warning to Thomas Tyrwhitt and the British officials who approved his plans in 1805. If Dartmoor wasn’t designed and operated as a modern prison, with humanity and dignity at its core, it might easily turn captives into criminals ■

The Hated Cage: An American Tragedy in Britain's Most Terrifying Prison

Oneworld Publications, 7 April 2022

RRP: £23.75 | 509 pages | ISBN: 978-1786079893

Buried in the history of our most famous jail, a unique story of captivity, violence and race.

It's 1812 – Britain and America are at war. British redcoats torch the White House and six thousand American sailors languish in the world’s largest prisoner-of-war camp, Dartmoor. A myriad of races and backgrounds, some are as young as thirteen.

Known as the ‘hated cage’, Dartmoor was designed to break its inmates, body and spirit. Yet, somehow, life continued to flourish behind its tall granite walls. Prisoners taught each other foreign languages and science, put on plays and staged boxing matches. In daring efforts to escape they lived every prison-break cliché – how to hide the tunnel entrances, what to do with the earth, which disguises might pass…

Drawing on meticulous research, The Hated Cage documents the extraordinary communities these men built within the prison – and the terrible massacre that destroyed these worlds.

"Beguiling." — The Times

"A vivid portrait." — Daily Mail

"This is history as it ought to be – gripping, dynamic, vividly written." — Marcus Rediker

Nicholas recommends:

⇲ The Society of Prisoners: Anglo-French Wars and Incarceration in the Eighteenth Century by Renaud Morieux (Oxford University Press, 2019)

⇲ Privateering: Patriots and Profits in the War of 1812 by Faye Kert (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015)

⇲ Quartz and Feldspar: Dartmoor - A British Landscape in Modern Times by Matthew Kelly (Jonathan Cape, 2015)

⇲ French and American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor Prison, 1805-1816: The Strangest Experiment by Neil Davie, (Palgrave, 2021)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Also Featured On

Travels Through Time Podcast: The Dartmoor Massacre with Nicholas Guyatt (1815)

Additional Credit

With thanks to Kate Bland at Oneworld Publications and Peter Moore.