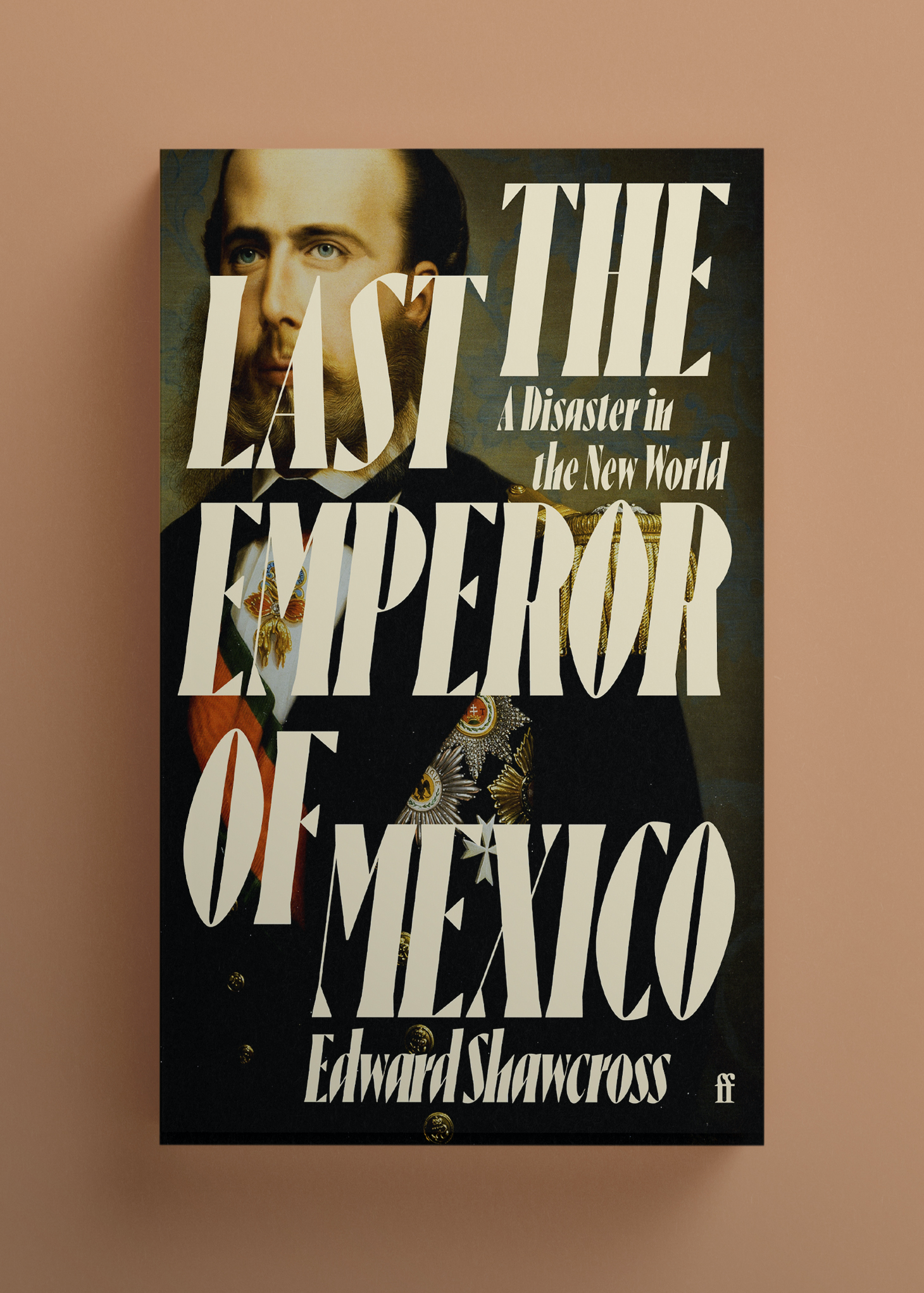

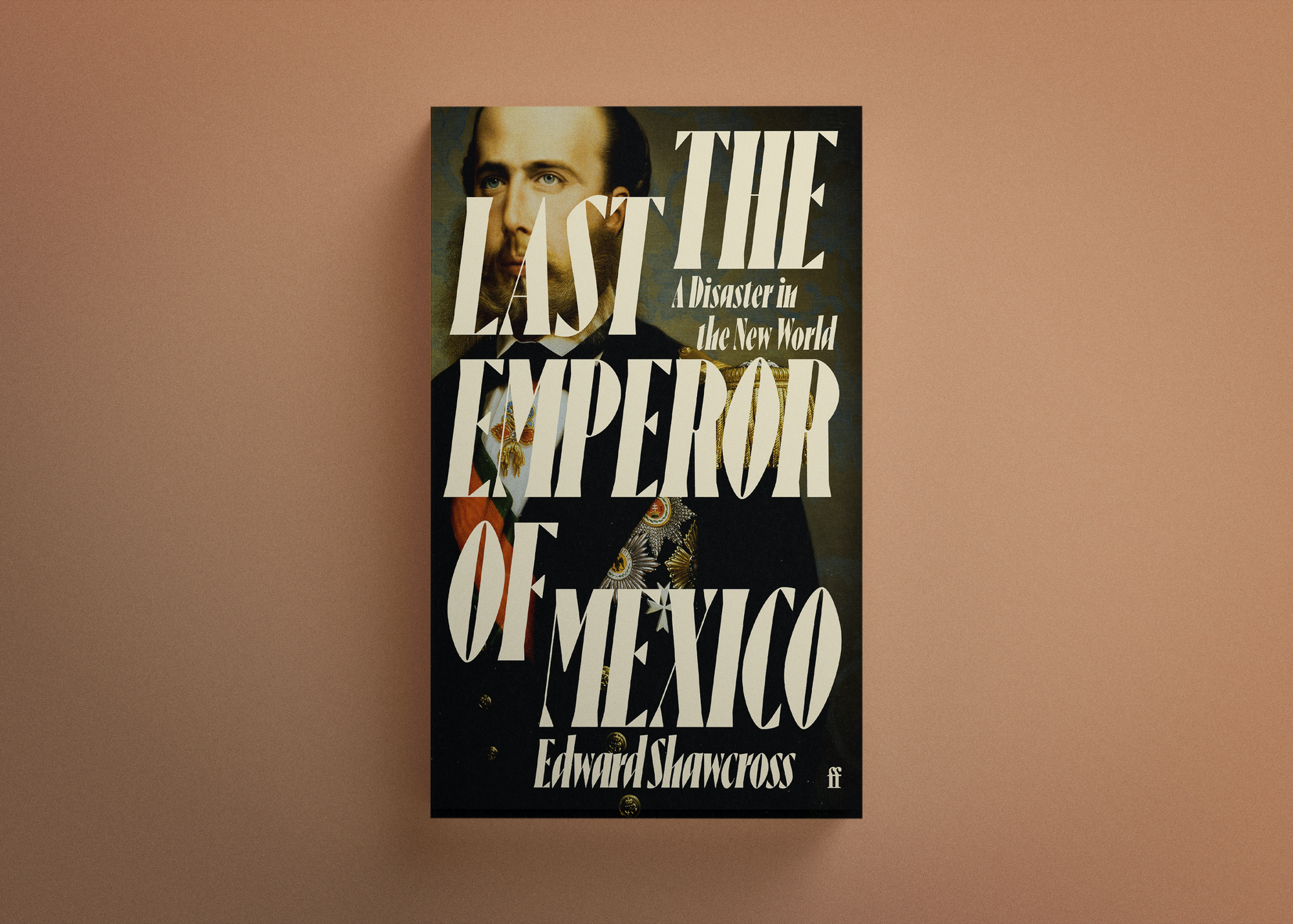

Excerpt: The Last Emperor of Mexico

A Disaster in the New World

The Last Emperor of Mexico recounts the ill-fated reign of Maximilian of Mexico, who in 1864 crossed the Atlantic to assume a faraway throne. The ensuing saga would feature intrigue, conspiracy and cut-throat statecraft, as Mexico became the pivotal battleground in the global balance of power, between Old Europe and the burgeoning force of the New World: American imperialism.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Edward Shawcross

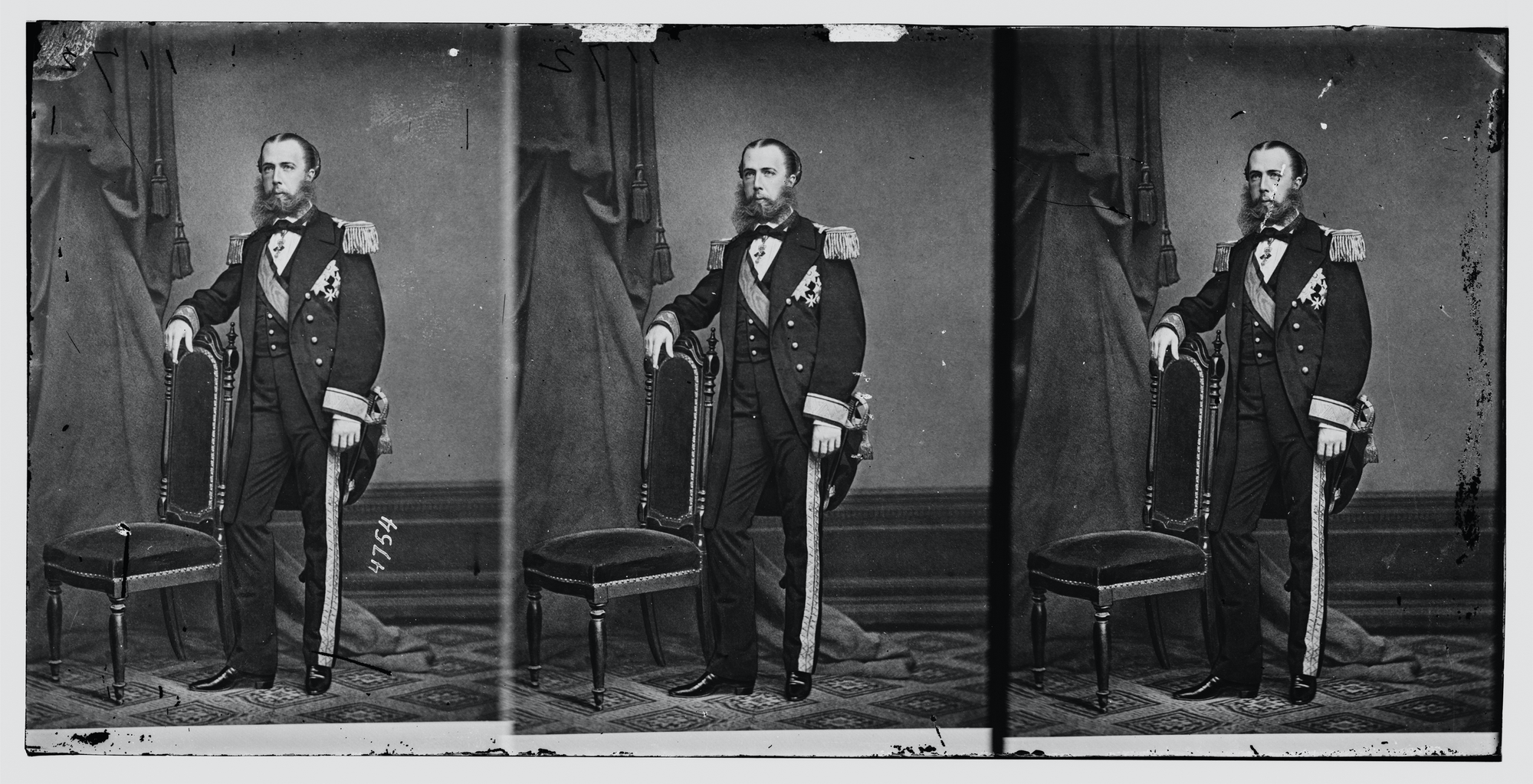

On 28 May 1864, Ferdinand Maximilian stared anxiously from his ship at the almost deserted docks of Veracruz, Mexico’s main Atlantic port. This dilapidated town, and the stifling tropical heat, were his first impressions of his new kingdom, for this Habsburg archduke had sailed from Europe to take up the throne as Maximilian I, emperor of Mexico.

Mexican exiles had offered him the crown almost three years earlier, in an effort to overthrow the republican government. The emperor of the French, Napoleon III, provided the troops for regime change. He sent some 30,000 soldiers to invade Mexico, forcing the legitimate president, Benito Juárez, to flee the capital. The French occupied Mexico City and set up a puppet regime that called on Maximilian to rule Mexico as its emperor. But – far from the cheering crowds he had been promised – when Maximilian arrived in his new kingdom he was met with cold indifference. Maximilian’s wife, Carlota, nearly cried as she and her husband were driven through the empty streets of Veracruz.

This inauspicious start proved prophetic. Although Maximilian won over some Mexicans, Juarista forces – those loyal to President Juárez – were determined to resist. At first, the imperialistas – as supporters of the empire were known – were in the ascendancy. But the tide turned in 1866 when Napoleon III announced that French troops were pulling out; foreign intervention had proved too costly in men and money to sustain. Carlota travelled to Europe to persuade the French emperor to change his mind. She failed, and never returned.

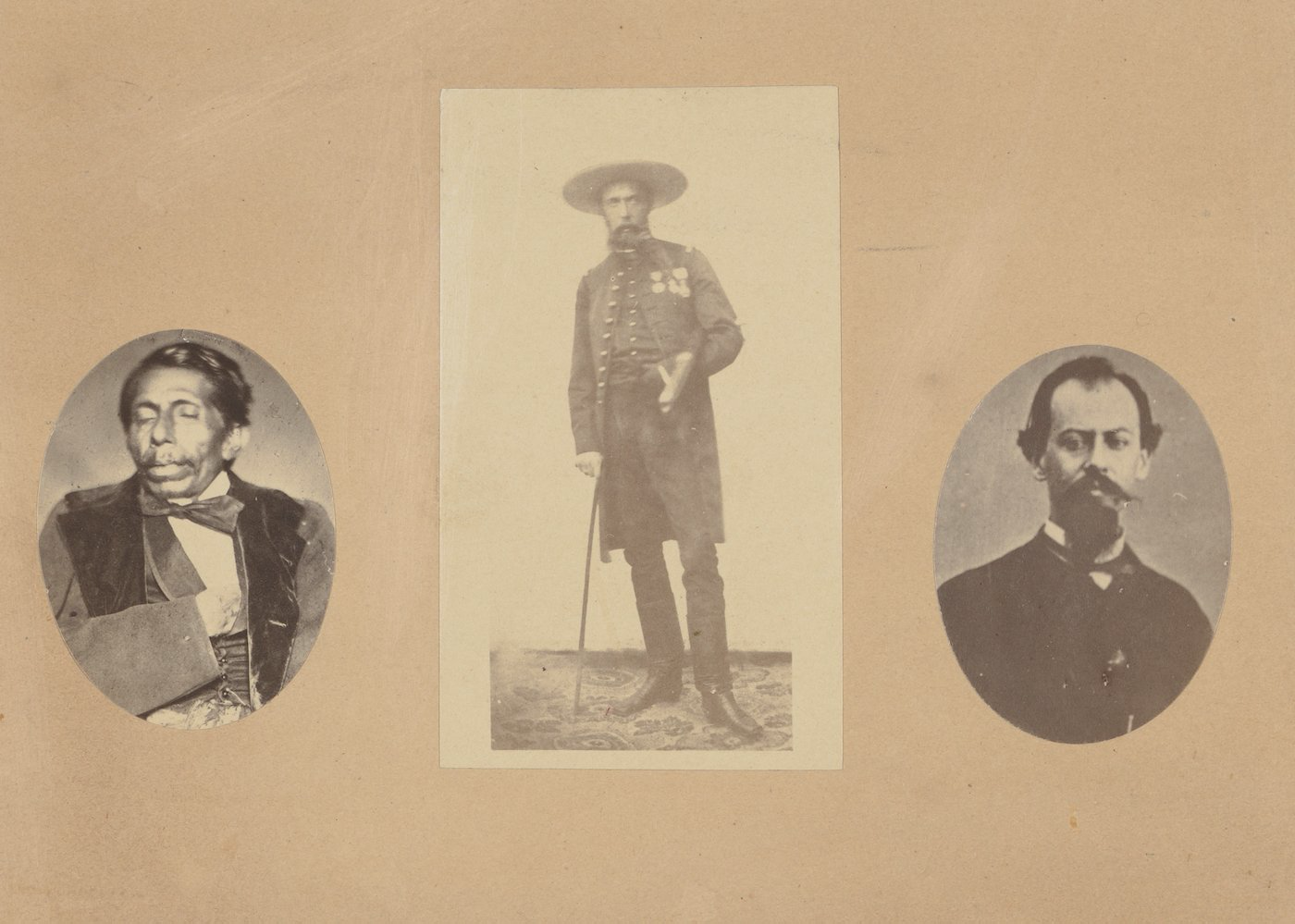

In Mexico, Maximilian concentrated what few troops he had left in the town of Querétaro in a last stand to save his empire. After a siege lasting from March to May 1867, he was betrayed by his formerly loyal lieutenant, Miguel López. Just three years after he arrived to take up his throne, he surrendered to Juarista forces. Maximilian was imprisoned and awaited his fate, along with supporters, including his loyal generals Tomás Mejíá and Miguel Miramón.

— Edward Shawcross

The Trial

An abridged excerpt from The Last Emperor of Mexico: A Disaster in the New World

When Maximilian’s health worsened, it was decided to move him to more salubrious imprisonment, another convent nearby. Too weak to walk, Maximilian went by carriage, his generals on foot. As the other prisoners caught up with him, respectfully removing their hats, Maximilian laughed and said, “No monarch can boast of a larger court.”[1] This court, made up of José Luis Blasio, Samuel Basch, and Felix Salm-Salm along with several other high-ranking imperialistas, was now crammed into a room adjacent to Maximilian’s.

Some of the emperor’s commanders refused to surrender themselves and hid in the town. Mariano Escobedo decreed that those who did not present themselves within twenty-four hours would be shot, but General Ramón Méndez refused to give himself up. It was not long before he was discovered. The next morning he was marched past the prisoners watching from the convent’s windows. Smiling and smoking a cigar, he offered his former comrades a cheerful wave. Later that day, he was escorted into the street, pushed to his knees against a wall, and then his guards readied to shoot him in the back as a traitor. As the order to fire was given, he turned round to face the guns on one knee and shouted “Viva Mexico!” before collapsing under the bullets.

This little reassured Maximilian and his fellow prisoners, but they at least received news of the outside world on May 20 when Felix Salm-Salm was reunited with his wife, Agnes, who had made her way to Querétaro from Mexico City. Seeing her husband for the first time in months, she recalled, “He was not shaved, wore a collar several days old, and looked altogether as if he had emerged from a dustbin”.[2] She wept as they embraced, nearly fainting. Felix then introduced her to the sick and pale emperor. It was from her that Maximilian learned of Márquez’s betrayal.

Maximilian already knew that instead of returning with men and money to Querétaro, his lieutenant-general had disobeyed orders and marched to Puebla, where his forces were routed. What Maximilian did not know was that Márquez still held Mexico City. Although Porfirio Díaz’s army surrounded the capital, Márquez not only had refused to surrender but, in a reversal of roles, now lied to the population, claiming Maximilian would soon relieve Mexico City. Hearing this, Maximilian offered to abdicate, surrender Mexico City to Juárez, and leave for Europe, swearing never to return. In informal conversations, Escobedo was amenable if noncommittal. Soon, however, the general received the order from Benito Juárez’s government that Maximilian was to be prosecuted under the law of January 25, 1862.

Put simply, this law condemned to death anyone who supported the French intervention. As the principal agent of that intervention, Maximilian was, of course, guilty. In case Escobedo was under any doubt, the order from Juárez’s government stated that the “notorious facts of Maximilian’s conduct include the greatest number of liabilities specified in this law.”[3] Moreover, under this law, a court-martial, not a civil trial, passed judgement. Military officers appointed from the republican army would decide the case.

Maximilian was moved to a more secure prison, another former convent, this time a Capuchin one. As his room had not been readied, Maximilian spent the first night in the crypt. Deep in the convent, the names of dead nuns carved on the walls, he spent the night amongst their tombs. It was to remind him, so a republican officer remarked, of what was to come.

The next day he was moved to a six-by-four-foot cell on the upper floor, with an uncovered window looking onto a large patio below where orange trees grew. With no more than a bed, a washstand, and a table, Maximilian made himself at home as best he could, hanging a serape over the window to give himself some privacy. A trunk with a few personal possessions had been found, and Maximilian arranged these neatly on the table alongside a silver candlestick holder. Whenever a visitor dislodged his possessions on the table, Maximilian became upset, hurriedly rearranging them. Mejía and Miramón, who were to be tried with Maximilian, were given adjoining cells.

As local lawyers prepared Maximilian’s defence, a telegram was sent to Mexico City to engage two prominent attorneys and request that foreign diplomats hurry to Querétaro to give international weight to the appeal. The capital, however, was still held by Márquez and under siege. Even if anyone could get out, the court-martial was due to start before they would arrive. Agnes Salm-Salm therefore went to San Luis Potosí to plead before Juárez for more time.

Although well aware of his wife’s powers of persuasion, Felix Salm-Salm was convinced that the court-martial would merely deliver a prejudged verdict of death. Escape, he explained to Maximilian, was the only way to save their lives. At first, the emperor was horrified, arguing that to run was dishonourable, but Salm-Salm convinced him that his honour had been satisfied through the heroic defence of Querétaro. The trial was a farce. He must save himself.

Salm-Salm’s bonhomie made him a favourite with the guards. He arranged to meet a liberal officer, plied him with wine, and then brought him into the plan. Opening the conversation, Salm-Salm said that he knew the officer had not been paid for months, but if he helped Maximilian escape he would give him $3,000. Salm-Salm then showed him the money before adding that once they reached Havana, he would receive another thousand ounces in gold. Thus having bought off the guard, Salm-Salm began to put the plan into effect. As they were under constant surveillance, Maximilian’s servant, who brought the prisoners breakfast every morning, hid coded notes in the bread. Salm-Salm’s task was made all the more difficult because Maximilian now insisted he would not flee without Mejía and Miramón. Undeterred, Salm-Salm managed to secure horses and revolvers for all of them.

On the morning of May 30, Salm-Salm discovered a note with his breakfast. Maximilian requested spectacles as a disguise for the escape. “On the horse must be fixed two serapes, two revolvers, and a sabre. Not to forget bread or biscuit, red wine and chocolate.”[4] The emperor refused to shave his distinctive beard, but agreed to tie it behind his neck and put on the glasses. The plan was to ride into the Sierra Gorda and then make for the coast and get to Veracruz, which was still under imperial control. There an Austrian ship would take Maximilian to Europe. The bribed officer, though, insisted that escape was not possible unless the commanding officer of the cavalry guard was also won over. Salm-Salm offered this man $5,000, and Maximilian signed a bill of credit for the sum. Everything in place, the guards bribed, early in the afternoon on June 2, Salm-Salm confirmed with Maximilian that they would slip away that same night.

But, the next day, the bribed guards were replaced, the number of soldiers on duty trebled, and surveillance intensified with random inspections of the prison cells. With escape now impossible, Maximilian’s life depended on the court-martial.

After Maximilian’s lawyers discussed the case with him, they concluded that the military tribunal at Querétaro was only a show trial. [Note from Edward: It was in Juárez’s cabinet where things would be decided, and so they went to San Luis Potosí to sway the outcome there. While there was no chance they could persuade Juárez that Maximilian was innocent, they were confident that their influence combined with the weight of international opinion would prevent the death penalty] After all, heads of state were not executed in the nineteenth century. Napoleon I, who had the entire continent of Europe united against him, was twice exiled rather than killed. More appositely, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, was currently imprisoned in Virginia for treason, but would ultimately be released and granted amnesty. And this was exactly what the man who had done so much to put Davis in prison recommended. If he were Mexican, Juárez’s most passionate US supporter, Ulysses S. Grant, reasoned, he would try Maximilian and then pardon him.

Awaiting the trial in prison, feverish and suffering from stomach cramps, Maximilian often stayed in bed until midday and then returned to it at about five. In the hours between, sunlight turned the small cells into furnaces, driving the prisoners into a gallery outside their rooms. There Mejía, Miramón, Salm-Salm, and Basch played dominoes with Maximilian to pass the time. When available, wine and cognac provided further relief. Although suffering mentally and physically, Maximilian still had hope for the future.

Maximilian maintained that he had been deceived and then abandoned by Napoleon III in Paris, while Bazaine had betrayed him in Mexico. From memory, he quoted the letter the French emperor had written: “What, indeed, would you think of me if, once Your Imperial Majesty had arrived in Mexico, I were to say that I can no longer fulfil the conditions to which I have set my signature?” The perfidy of France would be a key part of Maximilian’s public defence.

.jpg)

The Court-Martial

At eight on June 13, the court-martial began. Held in a theatre, named after Agustín de Iturbide, the first emperor of Mexico, executed in 1824, the symbolism was hardly subtle. The panel of judges comprised six captains, none older than twenty-four, with a lieutenant-colonel, in his mid-thirties, presiding. The trial took place on the stage, lit as for a performance, with the accused on stools. [Note from Edward: After Basch exaggerated his illness to the doctor appointed by the liberals, Maximilian was granted a certificate exempting him from appearing.] Mejía, who was seriously ill, and Miramón, despite the bullet wound to his face, were forced to attend. They appeared at nine, before an audience of a few hundred, mostly made up of military officers.

The prosecution accused Maximilian of thirteen counts under the January 25, 1862, law. The most important charges held that he had taken up arms as a traitor against the republic and that he had signed the Black Decree on October 3, 1865, which resulted in the unlawful deaths of thousands of Mexicans. The emperor’s defence denied the competency of the court, before refuting the charges against him and ending with an appeal to compassion.

It took only a day and a half for the court-martial to hear the prosecution and defence. They reached their verdict just before midnight on June 14, but would not release it publicly until Escobedo confirmed it. Maximilian’s legal representatives in Querétaro held out no hope and telegrammed Riva Palacio and Martínez de la Torre in San Luis Potosí to act as though the sentence were death. They immediately petitioned Juárez’s government to pardon Maximilian, receiving the reply that he could not be pardoned until the sentence was officially released.

At eleven on the morning of June 16, the prosecutor entered Maximilian’s cell and read the sentence. With a pale but calm face, Maximilian listened as he was told that he was condemned to death by firing squad. The officer as he left the room turned to Basch, tapped his watch, and said that the execution would be at three. “You still have more than three hours and can settle everything with ease.”[5]

Back in Querétaro, a priest arrived at midday to hear Maximilian’s confession. Mass was then performed in Miramón’s cell before the three condemned men received holy communion. In their final few hours, Miramón, Mejía, and Maximilian spoke with each other, trying to keep each other’s spirits up. Maximilian had Basch write letters of farewell, including one to Carlota. “Death is to me a happy release,” it ran. “I shall fall proudly as a soldier, like a king defeated but not dishonoured. If your sufferings are too severe, and God calls you to come and join me soon, I shall bless the hand of God which has been heavy upon us.” Fifteen minutes before the execution, Maximilian said his final good-bye to Basch. Handing the doctor his wedding ring, he said, “Go to Vienna. Speak to my parents and relatives and report to them about the siege and the last days of my life. Especially you will tell my mother that I fulfilled my duties as a soldier and that I died a good Christian.”[6]

As the clock struck three, no one arrived to take the men to the execution. Minutes passed, then an hour. Finally, Colonel Palacios appeared, telegram in hand. It was from Juárez’s government in San Luis Potosí. Palacios read it aloud. Maximilian’s execution had been postponed for three days. Upon hearing the news, Felix Salm-Salm, in prison awaiting his own trial, procured a bottle of wine to celebrate. Smoking a cigar and humming a tune, he paced up and down his cell excitedly. The postponement of the execution, he reasoned, could only be prelude to a pardon.

Everyone rallied to ensure this happened. Miramón persuaded the tearful Concepción Lombardo, baby and young children in tow, to go to Querétaro to plead for Maximilian’s and her husband’s lives. The irrepressible Agnes Salm-Salm accompanied her. Meanwhile, Maximilian’s lawyers protested that the three condemned men had confessed, received the sacrament, and thus already died morally. “It would be horrible to put them to death a second time”.[7] Magnus also reminded Juárez’s government that Prussia, all of Europe, and the United States wished Maximilian’s life spared. Finally, for his part, Maximilian telegrammed the president to ask for a pardon for Mejía and Miramón. If a victim was necessary, as he had said many times before, it should be only him.

The day before the execution, Agnes saw Juárez. When the president refused the pardon, she fell trembling and crying to her knees, desperately pleading for mercy.

When she stopped, Juárez replied, “I am grieved, madame, to see you thus on your knees before me; but if all the kings and queens of Europe were in your place I could not spare that life. It is not I who take it, it is the people and the law, and if I should not do its will the people would take it and mine also.”[8]

Concepción Lombardo, Maximilian’s last hope, was not even granted an audience. “Excuse me, gentlemen, from that painful interview”, Juárez told Maximilian’s lawyers who requested it. As they left the room, MartÍnez de la Torre suddenly turned and said, “Señor President, no more blood!”

“At this moment,” replied Juárez, “you cannot comprehend the necessity for [the execution], nor the justice by which it is supported. That appreciation is reserved for time.”[9]

The last-minute intervention on June 16 had been no prelude to pardon. Juárez had merely felt that the execution gave the condemned men insufficient time to put their affairs in order and postponed it for three days.

“I am at peace with the world,” Maximilian told Magnus the day before his execution. Maximilian’s only regret was that he had not been shot two days earlier. “We were completely prepared for death”, he remarked, and the delay was very hard to take. It had been a beautiful day, the sky clear and bright. “I have always wanted to die on a very clear day with good weather.”

The Execution

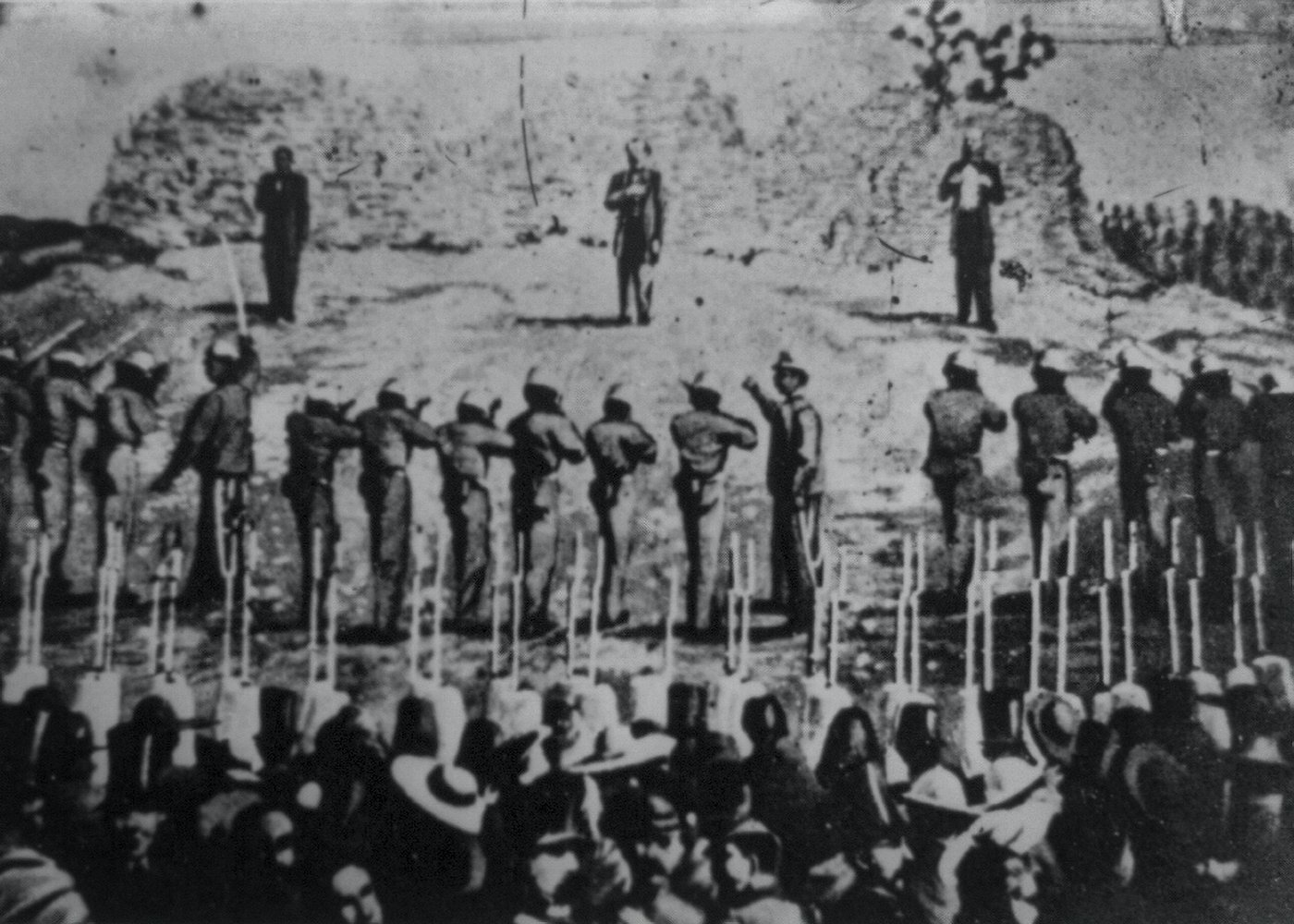

He woke at three thirty, and his confessor arrived shortly afterwards. At five, he heard mass with Mejía and Miramón and then breakfasted on coffee, chicken, bread, and a half glass of red wine. Shortly afterwards, the carriages arrived to take the three men to the Cerro de las Campanas, where they would be shot. Remaining serenely calm, Maximilian took off his wedding ring and handed it to Basch for the second time. The doctor broke down, unable to follow him out of the room. Seeing Miramón and Mejía waiting in the corridor, Maximilian asked, “Are you ready, gentlemen?” After they replied that they were, he hugged both men, and they made their way down to the street.

Dressed in black, with a buttoned frock coat and carrying a crucifix, the former emperor of Mexico climbed into the first of three black closed carriages. Under infantry and cavalry escort, this sombre procession made its way slowly towards the execution site, stopping at the foot of the hill. Getting out of his carriage, Maximilian saw a former servant in the waiting crowd. “Now do you believe that they are going to shoot me?” he asked.[10]

The three men took their final steps, each flanked by their confessor, towards the place of execution. Maximilian turned to Mejía and Miramón, embracing them one last time. “Soon”, he said, “we will see each other in heaven”.[11] With their backs to an uneven adobe wall, they took their places. Before them lay the town they had struggled to hold, a crowd of onlookers, and, directly in front of the condemned, the firing squad. From their executioners’ view, Maximilian was on the far right, Miramón in the middle, Mejía to the left. Turning to face straight towards his executioners, Maximilian spoke in clear, loud Spanish: “I forgive everybody, I pray that everyone may also forgive me, and I wish that my blood, which is now to be shed, may be for the good of the country. Long live Mexico, long live independence.”[12]

Miramón spoke next; Mejía stayed silent. Maximilian gave some money to his executioners, telling them to aim for his heart. The firing squad was barely five paces away, but he beat his hands against his chest, indicating where they should aim. Then he glanced up at the sky. He had got his wish. It was a cloudless day.

The shots rang out. Maximilian fell to the ground, and smoke gently wisped skywards from the bullet holes in his clothes as he lay dying in the Mexican dust ■

1. Samuel Basch, Memories of Mexico: A History of the Last Ten Months of the Empire, trans. Hugh McAden Oechler (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1973), 187.

2. Agnes Salm-Salm, Ten Years of My Life (Detroit: Belford Brothers, 1877), 190.

3. José María Vigil, La Reforma, vol. 5 of México a través de los siglos: Historia general y completa del desenvolvimiento social, político, religioso, militar, artístico, científico y literario de México desde la antigüedad más remota hasta la época actual, ed. Vicente Riva Palacio, 5 vols. (Barcelona: Espasa y Compañía, 1884–1889), 848–849.

4. Felix Salm-Salm, My Diary in Mexico in 1867, 2 vols. (London: Richard Bentley, 1868), 1:238–239.

5. Basch, Memories of Mexico, 214.

6. Corti, Maximilian, 2:817n46; Basch, Memories of Mexico, 215.

7. William Harris Chynoweth, The Fall of Maximilian, Late Emperor of Mexico (London: published by the author, 1872), 170.

8. A. Salm-Salm, Ten Years of My Life, 223.

9. Chynoweth, Fall of Maximilian, 174–175.

10. “Mexique”, Le Mémorial diplomatique, October 10, 1867.

11. Niceto de Zamacois, Historia de Méjico, desde sus tiempos más remotos hasta nuestros días, 18 vols. (Barcelona–Mexico City: J. F. Párres, 1877– 1882), 18:1512.

12. Corti, Maximilian, 2:822.

The Last Emperor of Mexico: A Disaster in the New World

Faber & Faber, 20 January 2022

RRP: £20.00 | 336 pages | ISBN: 978-0571360574

This is history's judgement on the events surrounding the ill-fated reign of Maximilian of Mexico, the young Austrian archduke who in 1864 crossed the Atlantic to assume a faraway throne.

He had been convinced to do so by a duplicitous Napoleon III. Keen to spread his own interests abroad, the French emperor promised Maximilian a hero's welcome, which he would ensure with his own mighty military support. Instead, Maximilian walked into a bloody guerrilla war - and with a headful of impractical ideals and a penchant for pomp and butterflies, the so-called new emperor was singularly unequipped for the task.

The ensuing saga would feature the great world leaders of the day, popes, bandits and queens; intrigue, conspiracy and cut-throat statecraft, as Mexico became the pivotal battleground in the global balance of power, between Old Europe and the burgeoning force of the New World: American imperialism.

The Last Emperor of Mexico is the vivid history of this barely known, barely believable episode - a bloody tragedy of operatic proportions, and a vital debacle, the effects of which would be felt into the twentieth century and beyond.

"Superbly entertaining." — Financial Times

"Baroque, page-turning and often grimly funny." — Tom Holland

"Hilarious, heartbreaking and utterly extraordinary." — Sunday Times

Edward recommends:

⇲ Santa Anna of Mexico by Will Fowler (Bison Books, 2009)

⇲ The Dead March: A History of the Mexican-American War by Peter Guardino (Harvard University Press, 2020)

⇲ Mexico's Crucial Century, 1810-1910 : An Introduction by Colin M. MacLachlan & William H. Beezley (University of Nebraska Press, 2010)

⇲ The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power by Martyn Rady (Penguin Audio, 2020)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Also Featured On

Travels Through Time Podcast: The Last Emperor of Mexico with Edward Shawcross (1867)

Additional Credit

With thanks to Connor Hutchinson and Faber. Author photograph © Edward Stone.