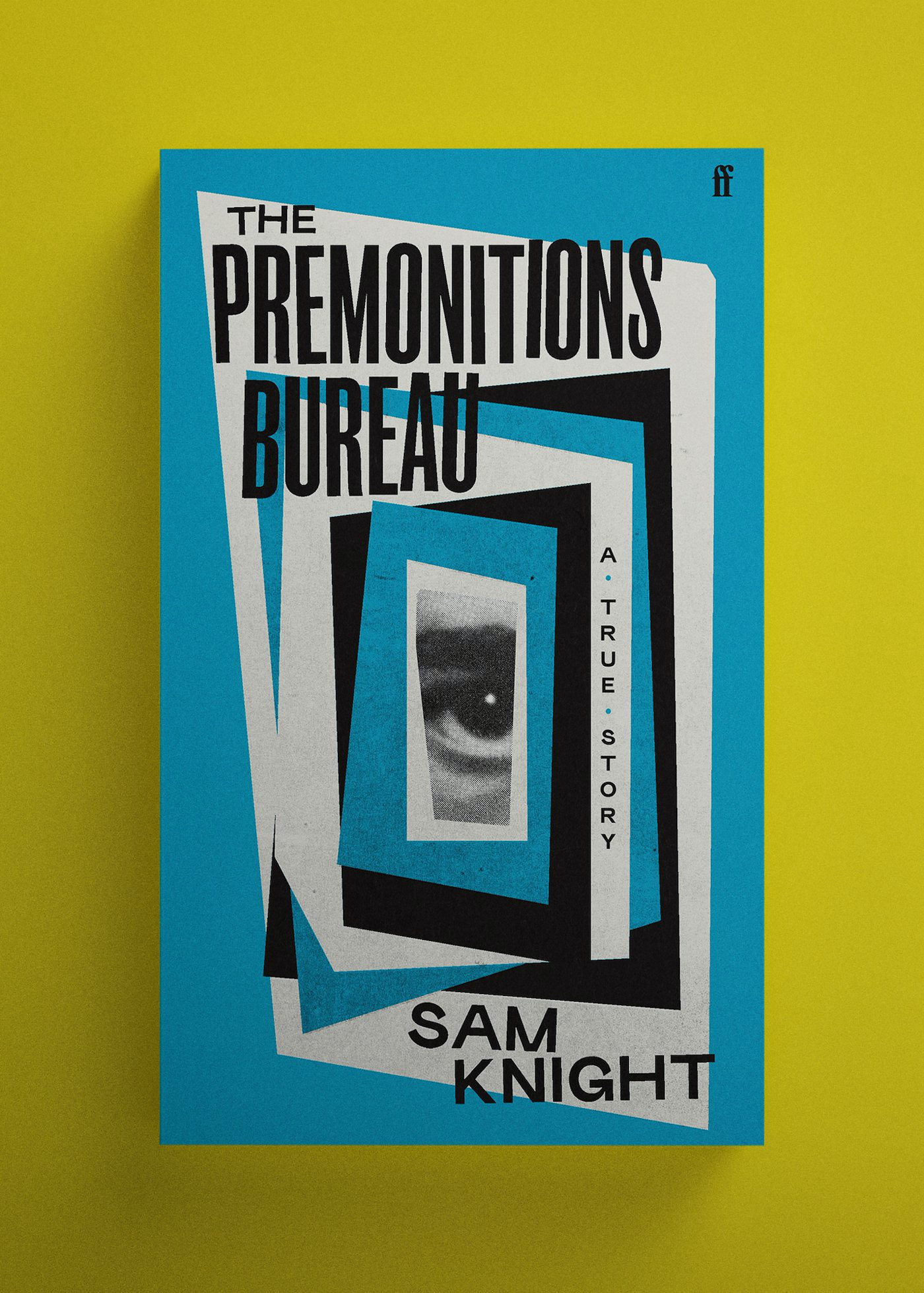

Excerpt: The Premonitions Bureau by Sam Knight

A journey into the oddest corners of 60s Britain and the outer edges of science and reason

Premonitions are impossible. But they come true all the time. You think of a forgotten friend. Out of the blue, they call. But what if you knew that something terrible was going to happen? In 1966, John Barker, a dynamic psychiatrist working in an outdated British mental hospital, established the Premonitions Bureau to investigate these questions. He would find a network of hundreds of correspondents, from bank clerks to ballet teachers. Among them were two unnervingly gifted “percipients”. Together, the pair predicted plane crashes, assassinations and international incidents, with uncanny accuracy. And then, they informed Barker of their most disturbing premonition: that he was about to die.

The Aberfan Disaster

An abridged excerpt from The Premonitions Bureau by Sam Knight

On the night of 20 October 1966, when she was fifty-two, Miss Middleton [a piano teacher living in north London] decided to stay the night at one of her parents' inherited properties, on Crescent Road in Hornsey. She was restless and slept in a spare bedroom on the first floor. The next morning, at around 6 a.m., she had a powerful feeling of foreboding. 'I awoke choking and gasping and with the sense of the walls caving in,' she wrote soon afterward.

A little more than an hour later, a group of labourers who were working on an enormous heap of coal waste in south Wales also paused to make a cup of tea. The team had a light-weight shack, with a coal fire, which they moved around on the hillside, depending on where they were working. It was a Friday morning – bright, windless, autumnal. The valley below was hidden under a layer of mist, which was pierced by the tall, square chimney of the Merthyr Vale Colliery. Since the First World War, spoil from the coal mine had been hauled up the side of Merthyr Mountain on a tramway. When the trams reached the top of the slope and an engine hut, they slid gently down a separate track to the summit of the tip, where a team of men, known as slingers, attached each tram to a crane and a crane driver swung the tram over the waste heap and turned it upside down. When a tip became too large, or caused trouble on the hillside, the engineers at the colliery would find a site for a new one. Tip number seven, where the men were working that morning, had been started in Easter 1958, after a local farmer complained that the previous tip, number six, had begun to encroach on his fields. The spot was chosen by an engineer and the colliery manager, who walked up Merthyr Mountain one day without a map.

Twice in 1963, waste on tip number seven had slipped down the hillside. That November, a hole opened in the heap which was eighty yards wide. By the autumn of 1966, tip number seven rose 111 feet above the slope. It contained enough slurry, tailings and mine detritus to fill St Paul's Cathedral one and a half times over. Weeks of heavy rain had saturated the hills and the coal waste balanced on top. When the slingers and the crane driver arrived at the summit, just before seven thirty on the morning of 21 October, they noticed that the surface had sunk about ten feet in the night. The tram tracks that led to the edge of the tip had fallen into a hole. A slinger, Dai Jones, was sent down the mountain to report the movement. There was no working telephone on the tip because the line had been stolen. While Jones was gone, Gwyn Brown, the crane driver, moved the crane back. By the time Jones returned with the leader of the team, Leslie Davies, at around 9 a.m., the top of the heap had fallen another ten feet. The men did not like what they were seeing. Davies passed on the news that the colliery engineers would select a new tipping site next week. Tip number seven was finished. Davies suggested that they make a round of tea before the men began the work of moving the crane and the rails. The slingers and Davies headed for the cabin.

Brown stayed by the crane and looked down the hillside. The valley was still carpeted by fog. There was no view of the close-packed terraces, churches and small shops of Aberfan. The village below was isolated but it was not rural, or even old. Before the mine there had been a single farmhouse and fields dotted with sheep.

As Brown glanced down, the heap rose up. It did not make sense. 'It started to rise slowly at first,' the crane driver later said. 'I thought I was seeing things. Then it rose up after pretty fast, at a tremendous speed.' Far below, at the base of the tip, thousands of tons of waste had liquefied and suddenly fallen. A dark, glistening wave burst out of the hillside and poured down, carrying the rest of the heap with it. "It sort of came up out of the depression and turned itself into a wave - that is the only way I can describe it,' Brown said. 'Down towards the mountain . .. towards Aberfan village ... into the mist.' Brown called out. The rest of the team stumbled from the shack, saw what was happening and ran down the slope, shouting warnings in the air. Their way was blocked by falling trees, trams, muck and slurry. The noise was tremendous. The men had all seen tip slides of a few hundred yards or so. But this was an avalanche. People in Aberfan later compared the roar of the tip to a low-flying jet aircraft or thunder or a runaway train as it swept down.

Sheep, hedges, cattle, a farmhouse with three people inside were smothered. The westernmost street in the village, which lies against the mountainside, is Moy Road. It was where Aberfan's two schools were situated: Pantglas Junior School and Pantglas County Secondary School. Classes at the junior school began at nine o'clock. The senior school got going at nine thirty. The wave reached them at nine fifteen, burying the primary school, which was full of children answering the register, checking the rain gauge, spelling the word p-a-r-a-b-l-e, paying their dinner money, delivering school sports reports, preparing to draw. Colliery trams and boulders crashed through the walls. The rear of the school was crushed beneath a dark heap thirty feet high. The gable ends of the roof poked through the waste. The senior school was only partially hit. Howard Rees, a fourteen-year-old boy on his way to class, saw the wave crest an old railway embankment above the village, 'moving fast, as fast as a car goes into town,' and crush three friends who were sitting on a wall. Eight houses behind them went too. George Williams, a hairdresser, saw doors and windows crashing inwards on Moy Road. Bricks flew. He was pinned under a piece of corrugated iron. When the roar stopped, Williams likened the sound to the moment after you switch a radio off. 'In that silence you couldn't hear a bird or a child,' he said. The first emergency call, from the Mackintosh Hotel, a pub further down Moy Road, was timed at 9,25 a.m. Miners, their faces blackened, lamps on their helmets, came up from the coal seams under the valley and were on the scene in twenty minutes. Water from severed pipes rushed through the streets, up to the rescuers' knees. One hundred and forty-four people were killed by the tip slide in Aberfan, 116 of them children, mostly between the ages of seven and ten.

The BBC broadcast a newsflash at 10.30 a.m. On the lunchtime news, which is how the prime minister, Harold Wilson, heard of the disaster, the death toll was given as twenty-six. By that time, Aberfan, which is tucked off the main road between Merthyr Tvdfil and Cardiff, was becoming clogged with press vehicles, ambulances, mobile canteens and earth-moving machinery. Nearby mines sent all manner of tractor shovels, bulldozers, excavators and trucks to clear the debris, but the tight corners of the schoolyard and the possibility of survivors in the slurry meant that the search was done almost entirely by hand. Every time a rescuer thought they had found something, a whistle blew and the place fell silent. No one was pulled alive from the wreckage after eleven o'clock in the morning. A dead girl was found holding an apple, a boy clutched at four pence. Children were found with birth certificates folded in their pockets. Some bodies were terribly disfigured. There was frenzy in the desire to help, to undo what had just occurred. People wanted to be useful even though it was not possible. At Merthyr hospital, people queued up to give blood, despite the lack of need. The switchboard at the colliery was jammed by incoming calls offering help in one form or another, making it impossible to find an outside line. Between one and two thousand people hurried to join the dig on Moy Road. Men cut themselves and bled in the muck. People stood on the waste heap, watching the effort, and caused it to crumble further, delaying the recovery. A bulldozer driver fell asleep at the controls. On the hillside above the village, miners and engineers worked to stabilise the rest of tip number seven with sandbags, which they filled with the slurry all around them. Near the school, around a hundred off-duty ambulance drivers hung around, refusing to go home. During the afternoon, higher-wattage bulbs were fitted in Aberfan's street lamps, floodlights were erected and the digging went on. Darkness fell and it grew cold. The prime minister came and went. Lord Snowdon, the Queen's brother-in-law, arrived at around 3 a.m. with a small suitcase and a shovel and was taken to the Bethania Chapel, the largest in the village, where the bodies were laid out on dark wooden pews marked by chalked letters - 'M' for male, 'F' for female, 'J' for juvenile - and a group of police detectives worked. Outside, a line of around fifty parents, mostly fathers, waited for hours to identify their dead.

The following morning, which was a Saturday, was overcast. The clouds spelled rain. Most people in the village had slept for only an hour or two. 'There was a greyness everywhere,' the Merthyr Express reported. ‘Faces from the tiredness and anguish, houses and roads from the oozing slurry of the tips.' There was more order and less hope, but the manic energy of the previous day persisted. A hundred lorries queued through the village to take away the mess. In twenty-four hours, the world had learned the name of Aberfan and its meaning: a place whose children had been buried alive by coal waste dug up by their fathers. If anything was needed at the disaster site, it arrived rapidly and in hysterical quantities. When a request went out for gloves, six thousand pairs turned up. The police asked for a piece of digging equipment known as a '955 shovel'; they received 955 shovels instead. Lorries that no one had sent for pulled into the colliery yard bearing tinned meat, shirts and tons of fruit. Chewing gum, soap, soup and bottles of brandy piled up wherever there was space.

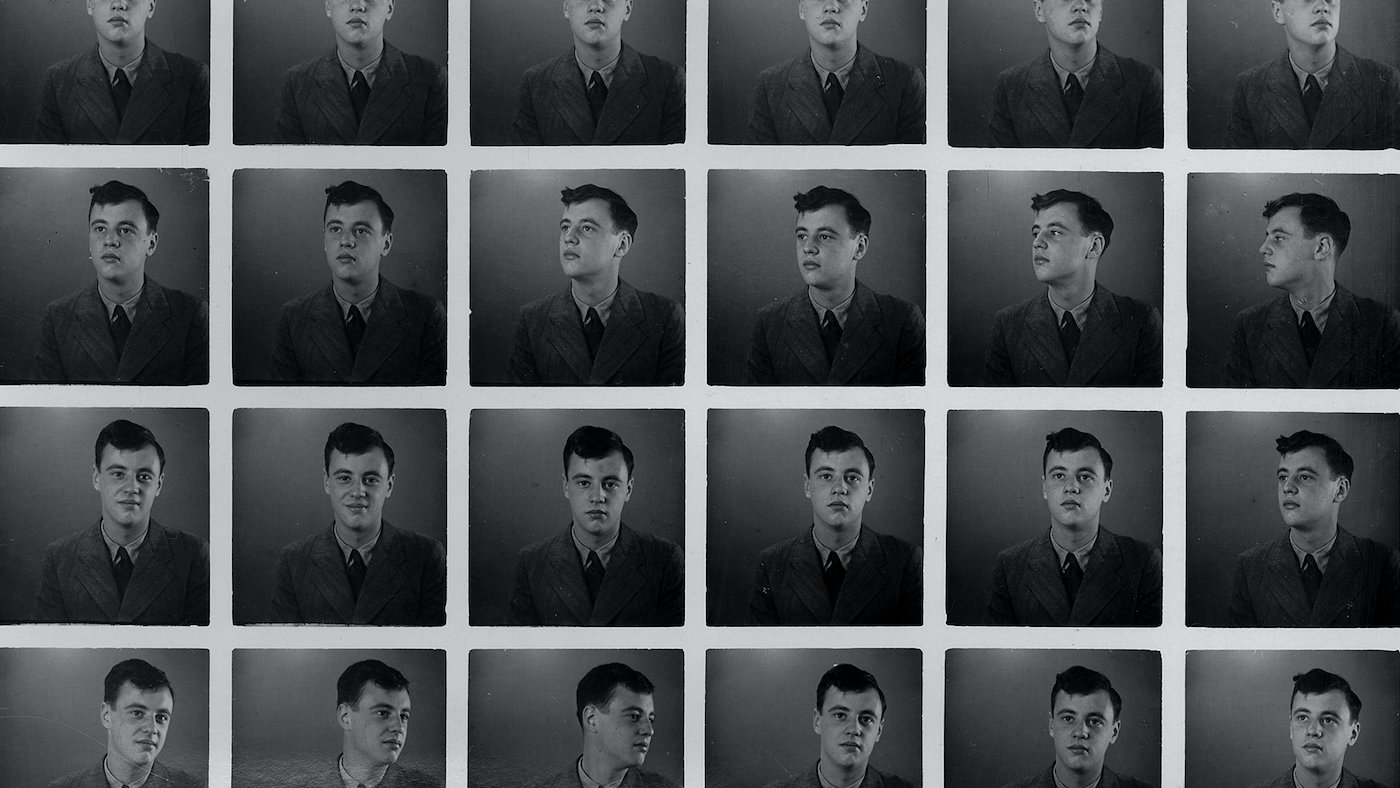

John Barker

There was a roadblock to control access to the disaster, but more or less anyone in a uniform or an official-looking car could find a way through. During the morning of 22 October, a dark green Ford Zephyr nosed its way into the village. At the wheel was John Barker, a forty-two-year-old psychiatrist with a keen interest in unusual mental conditions. Barker was tall and broad and dressed in a suit and tie. In his thirties, he had been very overweight. Since then, he had taken up exercise and dieted on rusks – hard, twice-cooked pieces of bread – with the result that his clothes now hung loose and he looked older than his years. He had bags under his eyes, fleshy lips and dark hair, which he wore combed forward. Barker was a senior consultant at Shelton Hospital, a mental institution outside Shrewsbury, a hundred miles east of the Merthyr valley, on the other side of the English border. At the time, he was working on a book about whether it was possible to be frightened to death.

In the early news reports from Aberfan, Barker had heard that a boy had escaped from the school unharmed but later died of shock. The psychiatrist had come to investigate, but realised he had arrived too soon. When Barker reached the village, victims were still being dug out. ‘I soon realised it would have been quite inopportune to make any enquiries about this child,' he wrote afterwards. He was appalled by what he saw. He was married and had three young children of his own. 'The experience sickened me,' he wrote. The devastation reminded Barker of the Blitz, when he had been a teenager, growing up in south London, but the loss of life in Aberfan was worse for being so concentrated and the dead so young. ’Parents who had lost their children were standing in the street, looking stunned and hopeless and many were still weeping. There was hardly anybody I encountered who had not lost someone.'

During the course of the day, a steady drizzle came down, soaking the hundreds of rescuers, muddying the streets deep in muck, and raising fears that the tip could suddenly fall again, causing another calamity. The village was dreadfully tense. First aid stations withdrew from the foot of the hill. A klaxon was readied to sound the alarm.

.jpg)

But Barker did not get back in his car and drive away. He had long been interested in subjects that struck others as macabre or inexplicable. He was, in every outward sense, an orthodox psychiatrist. He had studied at Cambridge University and at St George's Medical School in London. But he also chafed at the limits of his field. Barker believed that there was a 'new dimension' to psychiatry, waiting to be incorporated into mainstream science, if doctors could be persuaded to study problems and conditions that were mostly regarded as fringe or psychic. He was a member of Britain's Society for Psychical Research, which was founded in 1882 to investigate the paranormal, and for some years had been interested in the problem of precognition and people who seemed to know what was going to happen to them before it actually did. Barker was a modern doctor; he pursued his more esoteric inquiries with what he described as 'a conscious rationalism'.

But he also understood that there was an involuntary aspect to his research and that he was driven, like most of us, by influences that were profound and impulsive. At crucial moments in his life, when Barker was faced with a boundary or a warning, he pressed on.

In Aberfan, Barker sensed that he was on the scene of something momentous, though he wasn't sure what. Talking to witnesses, he was struck by 'several strange and pathetic incidents' connected to the disaster. A school bus, carrying children from Merthyr Vale, had been delayed by the fog and reached Moy Road after the tip fell. Their lateness saved their lives. A boy had overslept, apparently for the first time in his life, and was sent hurrying to school by his mother, in tears; he was crushed. Inane, unthinking decisions in the moments before the waste came down - a cup of tea before starting work, looking the wrong way, resting on a wall - spared lives and ended others.

.jpg)

Barker was interested in the nature of those decisions and what prompted them. Did people have rational fears or inexplicable knowledge? The dark, unnatural tips above Aberfan had long played on local people's minds. Bereaved families also spoke of dreams and portents. Weeks after the accident, the mother of an eight-year-old boy named Paul Davies, who died in Pantglas School, found a drawing of massed figures digging in the hillside under the words 'the end', which he had made the night before the slide.

Barker also heard the story of Eryl Mai Jones, a ten-year-old girl, 'not given to imagination', who had told her mother, Megan, two weeks before the collapse that she was not afraid of death. Why do you talk of dying, and you so young,' her mother replied. 'Do you want a lollipop?'

Then, according to a statement written by Glannant Jones, a local minister signed by Eryl Mai's parents and later published by Barker:

The day before the disaster she said to her mother, 'Mummy, let me tell you about my dream last night. ' Her mother answered gently, 'Darling, I've no time. Tell me again later.' The child replied, 'No Mummy, you must listen. I dreamt I went to school and there was no school there. Something black had come down all over it!'

The next morning, Eryl Mai was buried in the school ■

The Premonitions Bureau: A True Story

Faber & Faber, 5 May 2022

RRP: £14.99 | 256 pages | ISBN: 978-0571357567

The story of a strange experiment - a journey into the oddest corners of 60s Britain and the outer edges of science and reason.

Premonitions are impossible. But they come true all the time.

You think of a forgotten friend. Out of the blue, they call.

But what if you knew that something terrible was going to happen? A sudden flash, the words CHARING CROSS. Four days later, a packed express train comes off the rails outside the station.

What if you could share your vision, and stop that train? Could these forebodings help the world to prevent disasters?

In 1966, John Barker, a dynamic psychiatrist working in an outdated British mental hospital, established the Premonitions Bureau to investigate these questions. He would find a network of hundreds of correspondents, from bank clerks to ballet teachers. Among them were two unnervingly gifted "percipients". Together, the pair predicted plane crashes, assassinations and international incidents, with uncanny accuracy. And then, they informed Barker of their most disturbing premonition: that he was about to die.

The Premonitions Bureau is an enthralling true story, of madness and wonder, science and the supernatural - a journey to the most powerful and unsettling reaches of the human mind.

"A stunning piece of work. Brimming with mystery and suffused with haunting atmosphere . . . An enveloping, unsettling book, gorgeously written and profound." — Patrick Radden Keefe, bestselling author of Say Nothing and Empire of Pain

"A fluent and enticing book, skilfully navigating the tricky and marginal subject of the paranormal; it is beautifully ordered, humane, capacious." — Hilary Mantel

"An eerie and amazing account of coincidence and fate." — Emma Cline

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Also Featured On

Travels Through Time Podcast: The Premonitions Bureau with Sam Knight (1967)

Additional Credit

With thanks to Lauren Nicoll at Faber