Excerpt: The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley by Sean Lusk

The spellbinding tale of one young man’s quest for the truth in the 18th century

Raised amongst the cogs and springs of his father's workshop, Zachary Cloudesley has grown up surrounded by strange and enchanting clockwork automata. He is also the bearer of an extraordinary gift; at the touch of a hand, Zachary can see into the hearts and minds of the people he meets. But then a near-fatal accident will take Zachary away from the workshop and his family. His father will have to make a journey to Constantinople that he will never return from.

A beautifully crafted historical mystery that will take the reader from 18th century London, across Europe and, finally, to the bustling city of Constantinople.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Sean Lusk

Leadenhall Street, London, July 1760. Zachary’s father, Abel, a renowned maker of clocks and fabulous automata, is all too aware that some of his household believe his six-year-old son to possess special gifts, even the ability to see into the future. Abel is a rational man, uncomfortable with such fanciful notions. He loves his son with a ferocity that sometimes makes him uneasy, as he struggles to be both mother and father to Zachary, and tutor, too, knowing that he doesn’t quite succeed in any of those offices. He has resisted his late wife’s aunt’s attempts to raise Zachary as her heir at her country estate, in part because he cannot bear the thought of being parted from the boy and for fear that Aunt Frances’s many eccentricities – her aviary, her political campaigns, her drunken and neglectful household staff, might place Zachary in peril.

There is nothing Zachary likes more than to spend time in his father’s clockmaking workshop, where a clockwork peacock is being built for the king’s granddaughter as a birthday gift. But the boy is given to running about carelessly, and the real peril lies not at his great aunt’s estate but right here on Leadenhall Street.

— Sean Lusk

Life and Death

An abridged excerpt from The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley by Sean Lusk

March 1754, London

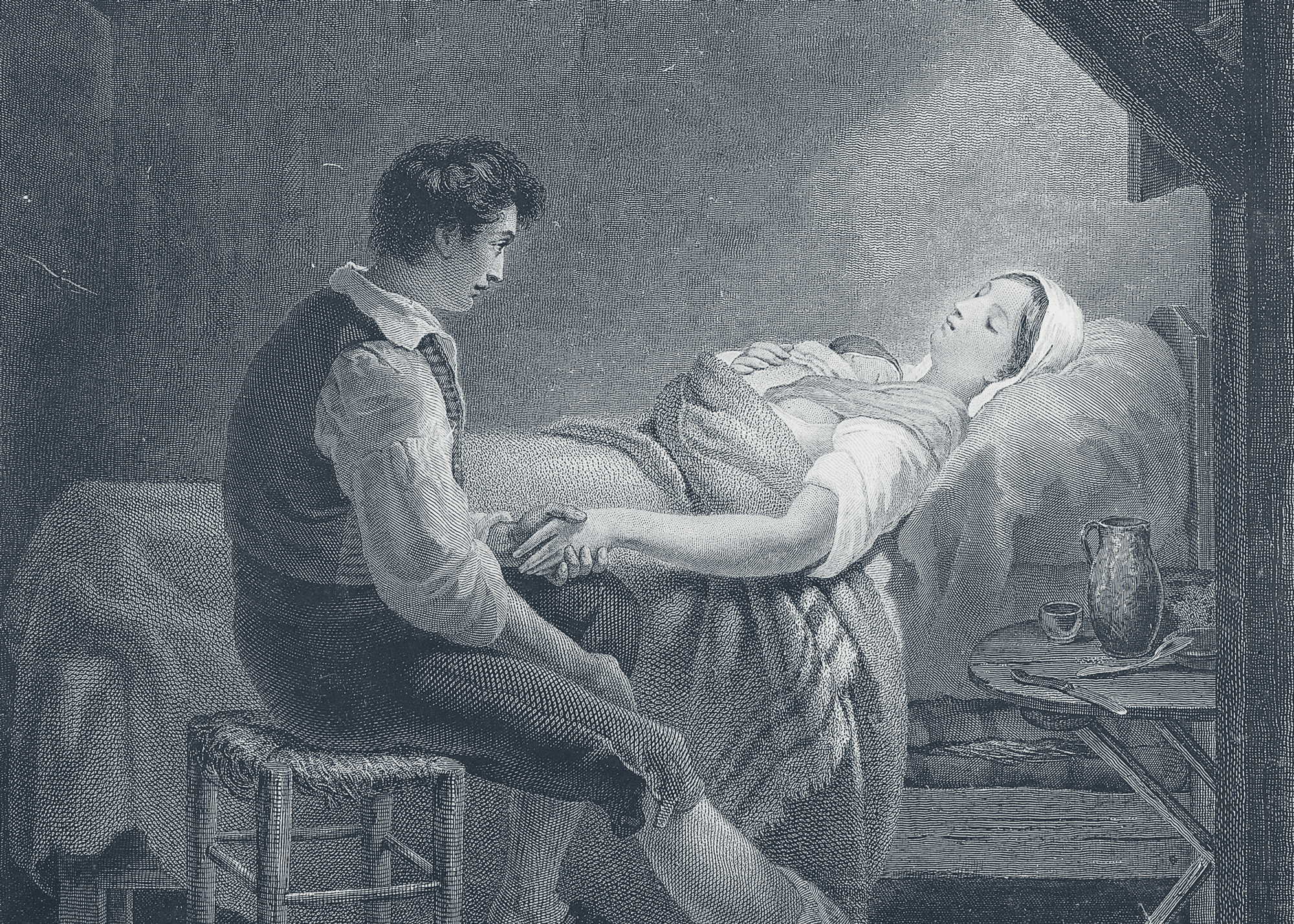

eadenhall stinks this morning; of soot and shit and, inexplicably, of nutmeg. Dr Pike has been in the bedchamber all night with Alice, ejecting Abel from the room four times already, wafting his meaty hand in the air along with words of greasy reassurance. It was Alice’s aunt who insisted they engage him, this pompous ‘midwifeman to ladies of distinction’, but he disgusted Abel from the first, there being something of the ox about the fellow, large and slow and clumsy so that he hardly seems the man for a woman’s parts.

Terror has crept up on him over the long hours of his wife’s confinement. At his last expulsion, not an hour before, she’d been too weak to offer him even her faint smile. ‘Go, Abel, go,’ she’d mouthed, and he’d felt her terrible disappointment in him; in everything. He has ceased to think of the unborn creature as a thing of hope and innocence and begun to conceive of it as an incubus, scrabbling its way out of his wife’s belly with devilish claws.

He takes a breath, a slower one, and tries to calm himself. A ladybird lands on his sleeve, drowsy, roused early from its hibernation, and he is grateful for the fleeting distraction. Putting a fingernail to its red and black shell he bids it fly, to escape while it can.

Another cry from above, this time Abel matching it with one of his own. A man scuttles past and, pausing, gives him an odd glance. ‘Good morning!’ Abel declares, feeling obliged to offer an explanation. ‘My wife is at the childbed. Those are her cries you hear.’ He craves the uncertain sympathy of another being, wants to discuss something inconsequential, as strangers do: the peculiar red dawns they have had that month, perhaps, or the heavy yellow mists that linger long after the breakfast hour. Striving for a jaunty tone, Abel confesses to the cries being his own, too, but the stranger gives him the barest of glances before striding on at even greater pace. ‘Lobcock!’ mutters Abel after his flapping coat, already vanishing into the mist.

The air is clearing, a thin sun breaking through the cloud. A little way along the street a boy leans so far out of an upstairs window that he seems sure to fall from it. Abel is about to shout out to him when he hears a cry from above, a baby’s lusty shriek. Every despairing thought flees as he turns and bounds up the stairs, his feet barely touching the wood as he flies, his heart keen and sharp. Ah, Alice! And Pike, good old Pike. He is the man, after all.

Stumbling into the room his first sight is of Pike’s back, his face turned towards the window. Next he sees Alice’s maid, Kate, whose features are twisted as if in fear, though he has never raised his voice to her or any of his household, nor ever would. In her hands she clasps the source of the cries, small but determined, its little face red and crushed as a rosebud in the hour before it opens. ‘I am sorry,’ declares Pike to no one in particular, his sorrow that of a craftsman dismayed with his work; hardly the sorrow of one mortal for another. ‘A weakness in the wall of the womb. A severe haemorrhage.’

It is what lies upon the bed that explains all, a vision of hell thrust into this world from another: Alice’s blue-white body twisted upon a rage of crimson blood. Abel rushes to her, presses his lips to her still-warm mouth and will not, cannot let go. After some minutes or years or lifetimes someone pulls him away and he cries out. Coming slowly to his senses he hears himself exclaiming hoarsely to all who might hear that he has murdered his wife with his own seed. Even the baby has fallen silent.

Pike and Kate watch him, Kate rocking the baby from side to side, regarding Abel as if he were a dog that might foam at the mouth and give her a mauling. Turning at last, Pike places a slab hand on Abel’s shoulder. ‘I have sent your servant to fetch out the reverend.’ Thinking he has not been understood, he repeats: ‘The priest is coming.’

Abel tries to respond, but all he can do is make a sound, a whinny like an injured horse. He knows he should reach out for the child, take it in his arms, yet there is something abhorrent in the prospect of fatherhood now.

Kate holds the swaddled bundle out to him, her face still stricken. Nervously she says, ‘You have a little boy, sir. A son, it is.’

Abel takes him and holds him, looking into his fierce dark blue eyes, their gaze fixed and penetrating, as unnerving as some creature wrenched from another universe entire, and asks him quietly whether he knows what a great calamity has accompanied his arrival, his tears falling on to his son’s face. He loosens the swaddling to examine the wonder of him more thoroughly, causing his son to squirm and whimper and grasp Abel’s index finger in his own tiny pink hand. He grips with such remarkable strength that it makes Abel wince. Are all newborns so strong, he wonders? Perhaps this resolve is what a motherless infant is given, as a fledgling cuckoo is given the vigour to push the other hatchlings out the nest and into oblivion. But there are no other chicks, thinks Abel. They are quite alone, the two of them, father and son.

Pike, who has been watching him cautiously, coughs. ‘I can attend to...’ He hesitates. ‘If you would like to leave the matter in my hands.’

Abel, holding the infant close to his chest, knows that Pike speaks of his wife’s body and tries to control his anger with a shake of his head. ‘I thank you, Mr Pike. Your services here are at an end – definitively so, as you see. I shall take care of matters now.’ He turns away but a few more bitter words spill in Pike’s direction without effort or intention. ‘No doubt the Reverend Hale will want to mumble his incantations, and then I shall call for the undertaker. I know him well, you understand. We have had regular trade these last few years: first my father, lately my mother, my sisters and now my wife. It’s a wonder he does not leave his hearse waiting outside my door.’

Pike moves to leave, the now useless bulk of him suddenly dark and looming in the shadowed room. Hesitating, he says, ‘Your son is strong, sir. Take some comfort in that. He is as strong a newborn as I ever delivered.’

Abel looks at him blankly. ‘He will need to be, will he not?’

With Pike gone there is an abrupt intimacy between Kate and Abel, so that he feels impelled to thrust his son into her waiting arms.

‘Shall I ask Grace Morley to be wet nurse, sir?’ she asks. ‘She has newly taken a room on Bishopsgate and not long had a little one of her own. She was born not two mile from my own home in Suffolk.’

Abel is silenced by the irony of it: three daughters born dead and poor Alice’s abundant milk an agony after each. Now a son born living and his mother has no milk for him because she has no breath, no life at all. A transaction must be made, he understands that; a woman must be found with milk to spare. His hand goes unconsciously to his own breast, as if by some miracle he will find a softness there, a swelling. ‘But Mrs Morley is a stranger to me.’

‘She is clean, sir.’

The baby cries and he sees the urgency in it. ‘Let it be Mrs Morley,’ he says without conviction.

‘She has a touch of palsy,’ says Kate over the baby’s protests, as if to safeguard herself from future criticism, ‘but no other impairments. Or none to speak of.’

‘Then let them not be spoken of,’ he says with a defeated smile. He does not feel like a man entitled to preferences now. He bids the maid leave him, his son in her arms. Alone, or almost, he becomes aware of the scent of blood and sweat and of something else; the tugging, sweet smell of fruit strewn on the ground and soon to rot, though the taste upon his tongue is of metal; indigestible and perpetual. He sits on the bed, taking Alice’s hand in his. Can this astonishing, clever, capable, funny, beautiful, stubborn woman really be gone from him, from everyone who ever knew her, from everyone she knew? Not two nights ago she had played the fortepiano loudly and badly for an hour, intending that all should share in her discomfort. She’d told Abel how different she felt this time, how strong the child was with his kicking and squirming and twisting. ‘He will leave me in a hurry, Abel, and jump, furious, into your arms.’ She had called him ‘he’. The thought that she was right, the knowledge that she will never see the boy makes him crumple. He slips from the bed to the floor, and weeps.

There is a knock at the door, so soft at first it might be nothing more than a shift of air, then more determined.

‘Come!’

The Reverend Hale enters, out of breath, his hat in his hand and his wig half off his head. He regards Abel, still prostrate, with sympathy. ‘I was prepared’ – his chest heaves – ‘but not for this, Abel. I am truly sorry.’

‘It is so.’ Abel stands, brushes himself down. ‘And I believe...’ He gestures towards the bed, but he no longer knows what it is he believes and his thoughts trail into silence. The vicar moves to where Alice’s body lies and delivers his prayers while Abel goes to the window and looks out on to the street, watching the scuttling movements of those below, as inconsequential to him now as mice arguing over breadcrumbs. Aware that Hale is standing beside him, he turns.

‘Have you thought of a name?’ asks the priest. ‘Perhaps Alice—’

‘Alice? For a boy?’ Abel frowns.

‘No, no,’ says Hale, gently, ‘I was not proposing the name Alice for the boy, merely wondering if dear Alice had expressed some preference, some . . .’

Abel turns to look once again at his wife’s body before leading Hale from the bedchamber and out on to the landing, having no wish to be overheard by the dead. ‘We dared not think of a name,’ he whispers, as much to himself as to the priest.

‘No, I understand. But a name is needed, nonetheless.’

Abel knows that Hale has a preference for speedy baptisms. The clergyman is a believer in efficiency, thinking that it is inefficiency that threatens faith, as if belief were the product of constant manufacture, and prayer a sort of flywheel keeping heaven aloft and God in His proper place.

‘What do you propose, Reverend?’ asks Abel, weary.

‘John is an ever-popular name.’

Needing to contradict Hale, needing to inflict some provocation simply to remind himself that he still lives, he says, ‘Perhaps an Old Testament name?’

‘Old Testament? Old Testament. Yes, well, there is Isaac, of course. Or Daniel.’

‘Hmmm.’

Warming to his theme, Hale offers other possibilities. ‘There is Absalom, who is the father of peace and I would wish that this child brings you peace, Abel.’

‘I think I shall have little of that now.’

‘Or Zephaniah. Zephaniah was hidden by God, and this child, too, his, his . . . goodness has been hidden from you, from us all, on this strange, dark day of fearful loss. And so—’

Abel places a hand on the minister’s shoulder. ‘Enough, Reverend. Zephaniah will do well enough. I like the idea of a name that begins with the end. It fits with Cloudesley, does it not? Or Zachary, perhaps.’

‘Zachary, yes,’ says Hale, relieved, ‘Zachary is serviceable.’ He turns and lurches down the stairs in pursuit of the infant, eager to begin his ministrations and no less eager to remove himself from Abel’s grief ■

The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley

Transworld Publishers Ltd, 9 June 2022

RRP: £14.99 | 368 pages | ISBN: 978-0857528056

Zachary Cloudesley is gifted in a remarkable way. But not all gifts are a blessing...

Leadenhall Street, London, 1754.

Raised amongst the cogs and springs of his father's workshop, Zachary Cloudesley has grown up surrounded by strange and enchanting clockwork automata. He is a happy child, beloved by his father Abel and the workmen who help bring his father's creations to life.

He is also the bearer of an extraordinary gift; at the touch of a hand, Zachary can see into the hearts and minds of the people he meets.

But then a near-fatal accident will take Zachary away from the workshop and his family. His father will have to make a journey that he will never return from. And, years later, only Zachary can find out what happened.

"Atmospheric, engaging, and elegantly written, this amazing tale of a clockmaker whose son possesses unusual talents is completely unforgettable." – Bonnie Garmus

"An original coming-of-age tale... enjoyable and imaginative debut" – Sunday Times (Historical Fiction Book of the Month)

"[A] dashing, magical debut . . . intricately plotted, and peopled with intriguing characters and cunning clockwork" – Daily Mail

Sean recommends:

⇲ Living Dolls: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life by Gaby Wood, (Faber, 2002)

A compelling account of the18th century obsession with mechanisms mimicking human and animal life, with a particular focus on the interplay between science and magic.

Eastern Clocks for the Eastern Markets by Ian White (The Antiquarian Horological Society, 2012)

A comprehensive and beautifully illustrated history of clocks and automata built for export to the Ottoman Empire and China in the 17th and 18th centuries.

⇲ The Earl and His Butler in Constantinople by Nigel and Caroline Webb (I B Tauris, 2006 )

An unusual view of the life of a diplomat in the Ottoman Empire, seen through the eyes of his servant and brimming with fascinating detail.

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Isabella Ghaffari Parker at Penguin RandomHouse.