Excerpt: The Story of Tutankhamun by Garry J. Shaw

An Intimate Life of the Boy Who Became King

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922 sparked imaginations across the globe. Tut-mania gripped the world—and in many ways, never left. But who was the “boy king,” and what was his life really like? Garry J. Shaw’s illustrated biography uses the most up to date research to present Tutankhamun as a person, rather than as a distant god-king or a symbol of ancient Egypt. Shaw’s compelling narrative weaves together numerous intriguing details from the boy king’s treasures and possessions, from a lock of his grandmother’s hair to a reed cut with his own hands, to reveal the life of this enigmatic young king and his modern rediscovery.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Garry J. Shaw

It’s been one hundred years since the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb – one hundred years since archaeologist Howard Carter held a candle through a long-blocked doorway and saw “wonderful things.” From that moment, Tutankhamun became a household name, resurrected from thousands of years of obscurity. Across the globe, there was wonder at the sight of his golden death mask. There was talk of mysterious curses. People speculated on why the nineteen-year-old pharaoh died so young. The focus was very much on death.

But after a century, what do we really know about Tutankhamun’s life?

Tutankhamun is sometimes dismissed as an unimportant king, one who left little impact on the world, but this is only because later pharaohs usurped his achievements and tried to erase him from history. In my new book, The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy Who Became King, I show that there is far more to the boy king than just his golden treasures.

He was a young man, who lost most of his family before the age of ten, married his half-sister, and tried, but failed, to have children. A king, brought up during a time of religious revolution, who turned his back on these heretical teachings to restore traditions that he’d never known. A figurehead, who presided over royal audiences and appointments, influenced by powerful courtiers. A pharaoh, who led religious festivals to ensure cosmic order and divine favour.

Without him, and the return to tradition that he symbolized, Egypt would have become a very different place over the centuries that followed. His life was a turning point in history.

Let me introduce you to Tutankhamun. This is his story.

— Garry J. Shaw

The Story of Tutankhaten

An excerpt from The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King

King Akhenaten sat beside Queen Nefertiti in the palace audience hall, each on a lion–legged throne, raised high on a dais above the people with gifts amassed below them. A gilded wooden canopy framed them, topped by two rows of rearing cobras – symbols of royal power, believed to spit fire at the enemies of order. The mood was good, and the royal couple held hands, breaking formality. Their six young daughters stood behind them, each sporting the long braid of plaited hair typically worn by children. While their parents watched the crowds assemble in the hall, they entertained themselves, smelling pomegranate fruits or playing with young gazelles, their royal pets. Among them was a princess named Ankhesenpaaten, the future wife of King Tutankhamun.

Akhenaten had been king for twelve years, and this grand celebration was the high point of his reign so far. His new city, Akhetaten, better known today as Amarna, had been under construction for the past seven years. Finally, it was complete, and not only was it the new home of his family, but it was the centre of operations for his government too, replacing Egypt's other royal cities. People from all over the country had already moved to Amarna to start a new life. Today, he had the chance to introduce it to the rest of the world.

On this grand day of celebration, while the royal princesses played, foreign delegations presented themselves before Egypt's king and queen, raising their arms in adoration and dropping to the floor to kiss the ground. The princesses watched as Nubians – people from the lands south of Egypt – stepped forward to offer leopards and antelopes, shields, gold rings, and blocks of precious metals, all carried in procession and placed on the audience hall's floor. The gold glinted in shafts of light cast from windows high up near the ceiling. Guards marched rows of prisoners of war, captured during a recent uprising against Egyptian control, their hands bound, feathers on their heads. Women and children walked among them. Some of the women carried babies in baskets strapped to their heads with bands. As the parade continued, men boxed and wrestled for the entertainment of the crowd. Guests chatted amongst themselves. Unfamiliar languages drifted through the air.

Next came the people of the Levant – vassal states of the pharaoh since the empire–building campaigns of Akhenaten's predecessors. They brought daggers, shields, chariots, animals, vases, and bound prisoners too – more unfortunates who would be sent to work in elite households and temple fields. Tribute also arrived from lands beyond Egypt's sphere of control The people of Punt, a place far to the south of Egypt, brought incense. The people of Libya, tall feathers in their hair, came carrying ostrich eggs. The Minoans of Crete offered luxury items crafted from metal.

When these foreign delegations arrived at Amarna, they saw an Egyptian city quite unlike any others they'd visited. The carvings of the king and queen appeared rather unflattering, showing them with spindly limbs and flabby bellies; the temples lacked their dark sanctuaries, and only one god was carved or painted on the temple and palace walls – a curious disc, high in the sky, its arms reaching downwards towards the royal family. Where was Osiris? Amun? Ptah? The gods they knew the Egyptians worshipped. Amun in particular seemed oddly absent, given his usual prominence. Wasn't he meant to be the king of the gods?

Akhenaten and Nefertiti knew the impact their unusual city, with its innovations in art, architecture, and religion, would have on visitors. Showing it off had been a great motivation for throwing the extravagant event unfolding before them. Stories of their grand architecture and artistic vision and – most importantly – their newly elevated god, the Aten, or sun disc, would spread to kingdoms far across the world. Now that Egypt's traditional state god Amun had been put in his place – his temples closed, his priests sent away, his statues smashed – Egypt could have a new and brighter beginning.

And from the Aten's point of view as he crossed the clear blue sky above his holy city, Akhenaten had created a marvel.

The god looked down upon a lengthy Royal Road that ran from north to south, parallel with the Nile. Designed primarily for royal parades, it was currently bustling with the chariots of dignitaries and servants, all making their way to the palace celebrations. The people of Amarna watched the spectacle from the sidelines, kept away by soldiers. Along the road's length, there were grand palaces, government offices, and huge temples, where hundreds of offering tables stood in the open air, piled high with gifts for the Aten's warm rays to touch. Smaller roads led eastwards from the Royal Road to the grand villas of Egypt's elite. Servants and the city's poor lived around these houses, while beyond on the city's desert fringes, workers quarried stone for their king, often malnourished, often dying young. To the east, in Amarna's lifeless hills, craftsmen cut and decorated tombs for the royal family and the elite, where after death, they would resurrect each day with the Aten.

The whole project was ambitious. Seven years earlier, none of this existed. Amarna had been a barren, empty space in the desert, lying just beyond the cultivated land on the Nile's east bank. Its swift construction was a testament to Akhenaten's devotion to his new god. This city would eternally be the Aten's cult centre and a home for Egypt's royal family, its chief worshippers. But absent from all this splendour and squalor, unseen and unmentioned in the monumental carvings and statues that commemorated the city's grand celebrations, was a three–year–old boy: Prince Tutankhaten – the future King Tutankhamun.

The Birth of a King

When Tutankhamun was born in 1329 BC, much of Amarna remained under construction. While servants and workmen quarried stone blocks and moulded mud–bricks for the temples, palaces and administrative buildings, and courtiers pondered the best spots to sink their private wells in the grounds of their new villas, Tutankhamun's mother was giving birth in a pavilion erected in the grounds of Amarna's North Riverside Palace – the royal family's main residence. She squatted, balancing, each foot on a mud brick to raise her from the ground, their sides decorated with protective imagery ensuring the safety of mother and child. Egypt's finest servants, midwives and doctors were at her call, armed with a mixture of ritual and magic to ease her pain and keep dangerous demons at bay. In a time when child mortality was high, and pregnancy was dangerous for the mother too, the fact that both survived the birth was surely a blessing from the Aten. She called him Tutankhaten, the 'Living Image of the Aten' in the god's honour. The royal doctors examined the child and found him healthy, except for a clubfoot distorting the bones and ankle. They searched their medical papyri for cures for his condition, but without success. He would walk with a stick throughout his life.

Tutankhamun's father was most probably Akhenaten, while his mother was one of Akhenaten's sisters. She died violently between the age of 25 and 35, when a heavy blow to the left side of her head fractured her skull – an injury from which she did not recover. Details of her life, including her name, remain a mystery. How much time Tutankhamun spent with either parent, or where, is also unknown. As a baby, Tutankhamun's wet nurse was Maia, a prominent woman in the royal harem. Given their time together, Tutankhamun perhaps formed a close bond with her, and maybe even saw her as a second mother, especially if his own mother died early in his life. The children of elite Egyptians were often assigned wet nurses. Princess Ankhesenpaaten – Tutankhamun's half–sister and future wife – had a royal nurse named Tia. Queen Nefertiti had a wet nurse named Tiye, wife of Aye, a royal adviser to Akhenaten, his nephew. Because of her proximity to the royal family, Tiye had the right to be represented throughout Aye's tomb, an honour infrequently given to wives.

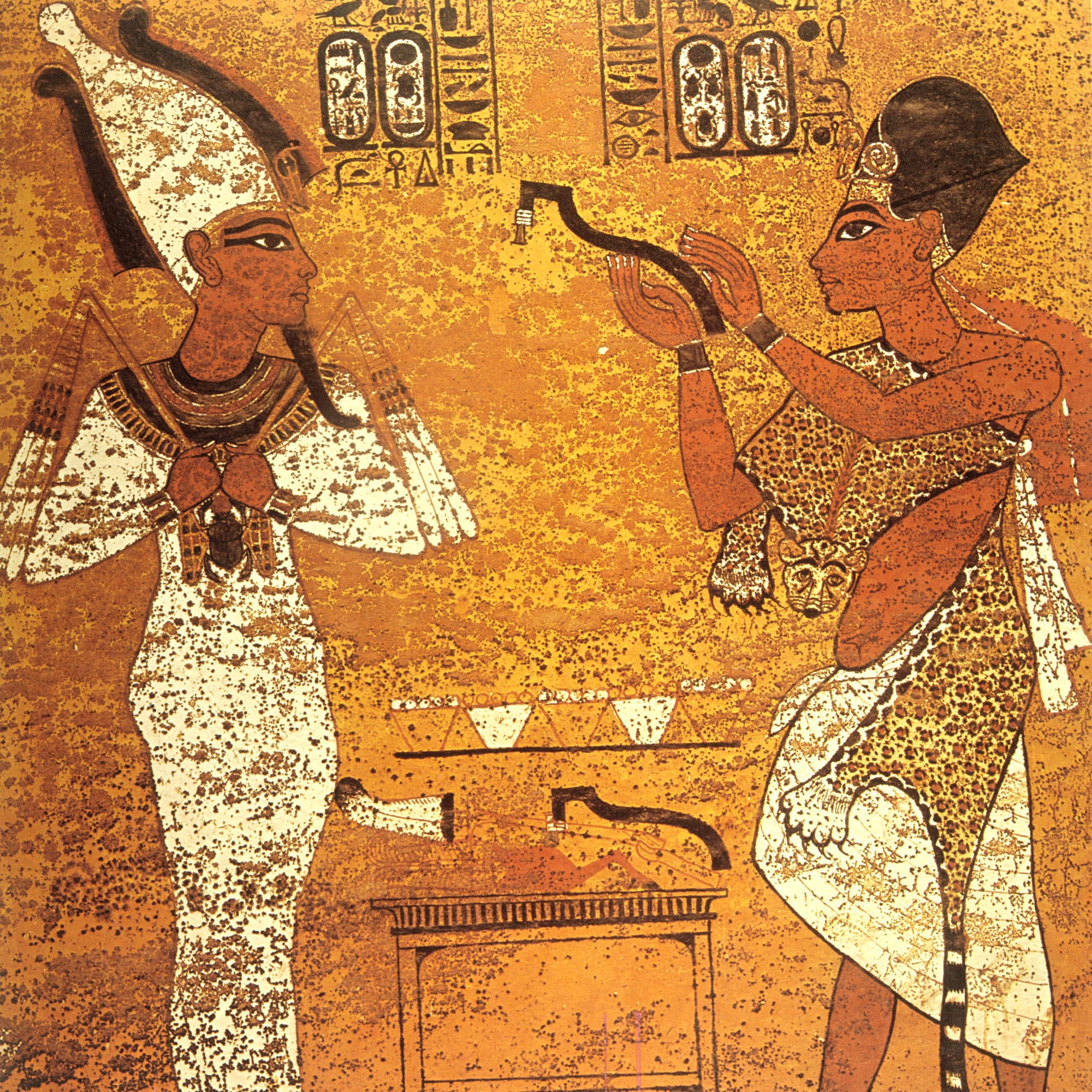

When Tutankhamun later became king, Maia would build a tomb for herself at Saqgara – a grand necropolis beside the great city of Memphis. Within, artists painted Maia sitting on a chair wearing a long flowing wig, crowned with a blob of sweet–smelling wax – an adornment often shown worn by guests at banquets. Tutankhamun sits on her lap, presented as a miniature king wearing the helmet–like Blue Crown. Maia raises one hand to Tutankhamun's face, her palm facing him in a gesture of respect. A dog, perhaps a royal pet, is beneath her chair. Given the closeness shown between nurse and child, it is possible that Tutankhamun himself authorized the painting – a reminder of the only parent he truly knew.

A Royal Education

Like any elite child, Tutankhamun owned a variety of toys. He played with an ivory monkey, whose arms he could move up and down, and a small wooden bird. He also had a fire stock and bow drill, which he could spin so the small bow created friction and heat, and ultimately, fire. But from around age four, there was less time for play. He now spent much of his life learning to read and write, sitting cross–legged on the palace floor, a papyrus pulled tight across his legs. He first studied hieratic, a cursive form of ancient Egyptian used in daily life, before moving on to learn the sacred hieroglyphs inscribed on monuments. Traditionally, scribes learnt to write a classical form of Egypt's language, a version spoken many centuries earlier. But Akhenaten was anything but traditional. As part of his reforms, he commanded people to write in the language of his day, making Tutankhamun among the first to adopt this new style. Nonetheless, there were still standard texts that every student had to learn. After writing simple words and phrases over and over, and studying model letters to build his vocabulary, he copied ancient classics, such as The Tale of Sinuhe, about a courtier who fled to the Levant. His tutors must have been careful to omit any references to the traditional gods in their study texts, and particularly any mention of the hated Amun.

There were wisdom texts to read too, particularly those that presented teachings passed from one king to the next – content that would have grabbed the young prince's attention. Among these was The Teachings for Merikare, already centuries old by Tutankhamun's era. Set during a time of political break–down, the pharaoh instructs his son on the weight of kingship, and gives wise advice on the importance of discussion over violence, respect for people and monuments, piety, and how officials should be appointed based on ability rather than status. Composed during the same period, The Teachings of Amenemhat, relate how the king, after being attacked, teaches the crown prince that no matter how well he ruled, there was always danger, even within the palace. To Amenemhat, kings had no place for trust.

As a prince, Tutankhamun had access to the best scribal equipment in Egypt. He owned an elaborate wooden holder for the reed brushes he used as pens; inlaid with precious stones and gilded, it was designed to appear like a palm tree. Any mistakes that he made when writing on papyrus were rubbed away with a handy piece of sandstone. His scribal palettes were inscribed with his name, and had dedicated sections for his 'cakes" of black and red ink, which he mixed with water. He used one of his ivory bowls so often that it became stained with red ink. Given that red was often used for corrections, perhaps he made a lot of mistakes. Tutankhamun wasn't the only royal family member who learned to write. His half-sister, Meketaten owned an ivory scribal palette, which had four spaces for pigment, filled with red, yellow and black colours. She was only a few years older than him, so they may have learned to write together. A palette owned by his oldest half-sister, Meritaten, had space for six colours, of which blue was her favourite.

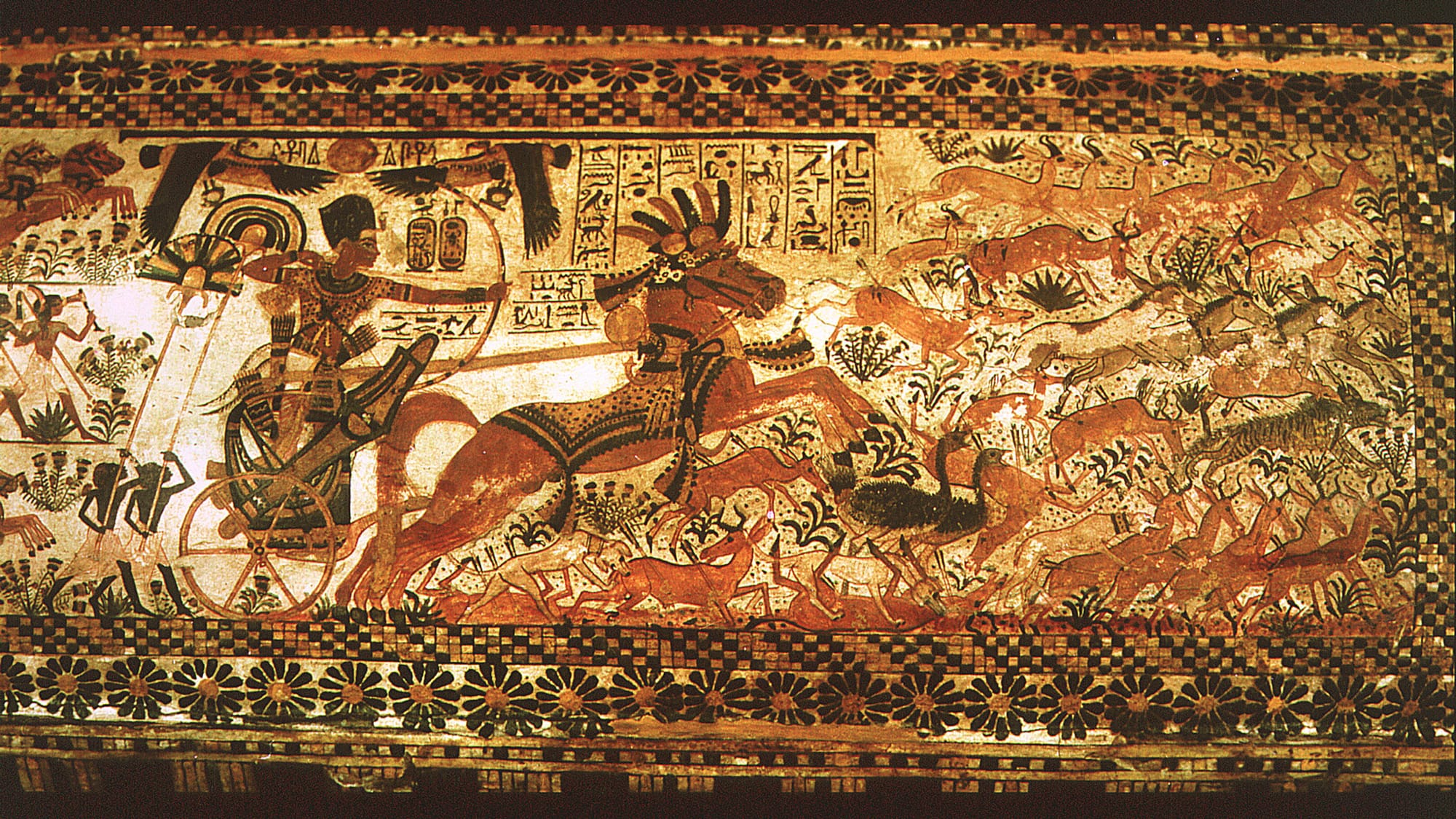

Princes were normally educated in the palace alongside other royals and select members of the elite, including the children of foreign rulers from regions under Egyptian control. The royal children also travelled to Egypt's provinces to learn from tutors outside the major cities. Sennedjem, Tutankhamun's royal tutor, came from Akhmim, around 150 kilometres south of Amarna, so it was perhaps there that he gave the prince chariot riding lessons, improving his hunting skills and preparing him for a future as a war leader. On these occasions, Tutankhamun wore child–size gloves, designed for charioteers, and socks that kept his feet safe from the dust and stones thrown into the air. He owned small bows and when shooting arrows, to save his left wrist from harm, he wore wrist–guards made from leather. He also had a sling, which he used when hunting.

Tutankhamun's other tutors would have been enlisted from the government administration. Given past precedent, treasurers, royal stewards, and even the vizier – the highest office in the land after the pharaoh – might have been called on to teach him. From these assorted dignitaries, he would have learnt management, geography, diplomacy, warfare, religion, court etiquette and morality. All of these skills would have been useful to Tutankhamun, for even if he never became king, princes were sometimes appointed to offices in the administration, military, or the priesthood.

The Teachings of Akhenaten

Thanks to Akhenaten's religious reforms, the Aten was now Egypt's state god, and all other deities were to be ignored. In particular, though, it was Amun, the Hidden One, who received his greatest scorn. Not only did Akhenaten change his name from Amenhotep, removing Amun, he ordered this god's images and names be hacked away from all monuments. With royal approval, the old ways were dead. In this new dawn, the teachings of Akhenaten were central. The Aten taught the king and he passed its words on to the people. According to him, the Aten was the creator of the world, of all people, of animals.

When the god rose in the morning, he brought joy to all lands. People celebrated and the king made offerings to him. And when he set, the darkness brought dangers and a death–like state, which was only eradicated by the morning light and the rebirth it signified. The traditional gods had no role in this daily drama, to the extent that hieroglyphs spelling out the word 'gods" in the plural, were made singular. It's probable, then, that alongside Tutankhamun's traditional curriculum, in his earliest years of learning he received teachings directly or indirectly from his father.

While Tutankhamun studied and enjoyed his youth, either at Amarna or travelling around Egypt to visit tutors, destruction was never far away. For every beautiful new palace or villa he saw erected at Amarna, there was a temple to a traditional god falling to ruin somewhere else. Perhaps on his travels, he watched his father's followers taking chisels to images of the gods, disfiguring them beyond recognition or smashing away their faces; or he looked on as they scratched off the gods' sacred names from temple walls. Because Tutankhamun was educated in the modern ways of Akhenaten and the Aten, this must have all appeared very normal – expected even, given that the old ways were being swept away and replaced. After all, who needed Amun, or any of the old gods, when you had the Aten? Simultaneously though, when passing through the streets of Amarna on a chariot, or carried in his palanquin, he couldn't avoid seeing symbols of the old faith. People – even at Amarna – made no secret of wearing amulets to traditional deities and worshipping them in their homes. All the contradiction and confusion, the destruction and construction, must have left an imprint on the child prince. Unless Tutankhamun's early tutors taught him about Egypt's traditional ways, his first experiences of temple worship would have been quite different from princes born before or after him ■

The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King

Yale University Press, 11 October 2022

RRP: £16.99 | 192 pages | ISBN: 978-0300267433

A lively new biography of Tutankhamun―published for the hundredth anniversary of his tomb’s modern discovery

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 sparked imaginations across the globe. While Howard Carter emptied its treasures, Tut-mania gripped the world―and in many ways, never left. But who was the “boy king,” and what was his life really like?

Garry J. Shaw tells the full story of Tutankhamun’s reign and his modern rediscovery. As pharaoh, Tutankhamun had to manage an empire, navigate influential courtiers, and suffer the pain of losing at least two children―all before his nineteenth birthday. Shaw explores the boy king’s treasures and possessions, from a lock of his grandmother’s hair to a reed cut with his own hands. He looks too at Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun’s wife, and the power queens held. This is a compelling new biography that weaves together intriguing details about ancient Egyptian culture, its beliefs, and its place in the wider world.

"Garry Shaw has done a remarkable job synthesizing everything we know and do not know about Tutankhamun. . . . Stunning color photos . . . add to the tale." – Kelly Macguire, World History Encyclopedia

"This exceptional account not only brings the reign of Tutankhamun back to life, it also shows the ruler in a new light, not only as king of ancient Egypt, but as a human being." – Christina Geisen, University of Cambridge"

"Shaw's compelling portrait of the young pharaoh in life and in death is based on the latest research and impeccable sources . . . This brilliant achievement will appeal to anyone interested in archaeology and ancient Egypt. A lovely book!" – Brian Fagan, author of Lord and Pharaoh

Garry: Here are some book suggestions to help you deepen your knowledge of Tutankhamun:

⇲ Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation by Aidan Dodson (Revised edition, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2018)

⇲ The Unknown Tutankhamun by Marianne Eaton-Krauss (Bloomsbury Academic, London and New York, 2015)

⇲ Discovering Tutankhamun. From Howard Carter to DNA by Zahi Hawass (The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2013)

The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy by Jo Marchant (Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2013)

⇲ The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure by Nicholas Reeves (Thames & Hudson, London, 1990)

⇲ Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century by Christina Riggs (Atlantic Books, London, 2021)

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Kate Burvill and Yale University Press. Alamy images reproduced under licence.