Excerpt: Time's Echo by Jeremy Eichler

The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance

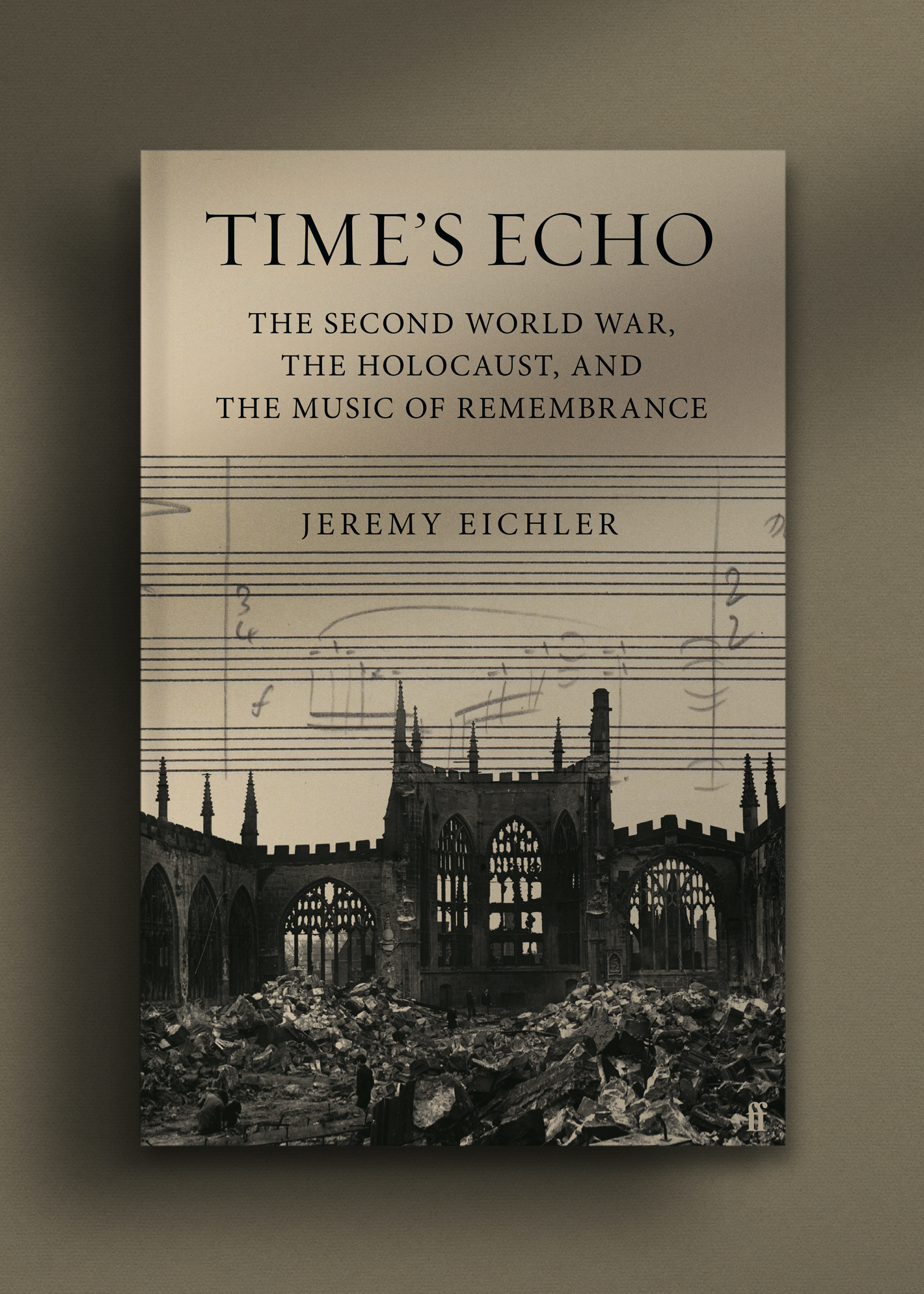

Time's Echo is one of the six books shortlisted for this year's Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction. Written by the critic and cultural historian Jeremy Eichler, it seeks to reimagine the power and presence of art in our lives today by exploring music's role as a carrier of cultural memory and meaning from the past.

In Time's Echo Eichler concentrates on the work of four pre-eminent composers: Dmitri Shostakovich, Benjamin Britten, Arnold Schoenberg, and Richard Strauss. All of these lived through the traumas of the early twentieth century, of war and totalitarianism, and each responded in a distinctive way.

Benjamin Britten's 'War Requiem' is one instructive piece. First performed in 1962 at the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral, it was an artistic response to the destruction of the former cathedral by the luftwaffe in 1940. And yet in his commemoration of this event Britten used the words of the First World War poet Wilfred Owen.

In this exclusive excerpt from Time's Echo, Eichler reflects on this puzzle. Why did Britten choose to commemorate the Second World War through the poetry of the First?

The mighty convulsions ... are perfectly capable of extending from the beginning of time to the present. What would we think of a geophysicist who, satisfied with having computed their remoteness to a fraction of an inch, would then conclude that the influence of the moon upon the earth is far greater than that of the sun? Neither in outer space, nor in time, can the potency of a force be measured by the single dimension of distance.

— Marc Bloch, The Historian's Craft*

On the morning of November 10, 1946, a bright day in Central London, thousands of mourners turned out to pay official tribute to the war dead of the British Empire. Unlike their early postwar New York counterparts, who eleven months later would gather around an empty site to dedicate an unbuilt memorial, the crowd in London had their monument at the ready. Indeed, no new construction had been required because at the heart of the morning’s civic ceremony stood the austere and noble Cenotaph, erected with great fanfare in 1919 and inscribed to “The Glorious Dead” of the First World War. As the mourners settled into their places, its grayish Portland stone gleamed in the fall sunshine.1

On this particular second Sunday of November, following the well-established Armistice Day tradition, when Big Ben tolled eleven o’clock, a gunshot was fired from the Horse Guards Parade marking the official start of a hallowed two minutes of silence. This year in Whitehall the quiet was pristine, marred only by the vague rumbling of a distant airplane to the west and the whispering of the leaves on the plane trees. At the end of the silence, another shot was fired and RAF trumpeters sounded the mournful tones of the Last Post, a bugle call akin to taps. Then, just as in years past, King George and Princess Elizabeth solemnly placed wreaths at the foot of the monument. Other members of the royal family looked on, dressed in black and wearing pins with red poppies.

The poppies were of course the well-established symbol of First World War remembrance, originally inspired by the poem “In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae. Yet in the decades following the Second World War in the U.K., these earlier rituals of remembrance proved to be surprisingly elastic as more recent losses were simply folded into the established scripts of commemoration. In fact on this very day, the new union of the dead from disparate wars would be officially ratified by the holiday’s name change, from Armistice Day (with its limiting First World War associations) to the more generalized Remembrance Day. In the same spirit, older civic symbols of commemoration were swiftly retrofitted. From this day forward, poppies would be worn in memory of all of the empire’s fallen soldiers, and its most important war monument had likewise received a touching up all its own. Just before the start of the two minutes of silence, the king, wearing the gold-cuffed uniform of the Admiral of the Fleet, stepped forward and pulled a tasseled cord to reveal a brand-new inscription: the dates 1939 and 1945 in Roman numerals had now been added to the Cenotaph, joining the dates 1914 and 1918. As one editorial opined, this consolidation of remembrance was “as it should be, for the ‘glorious dead’ of the two wars are already one in national recollection and honour.”2

Another reporter noted in passing that with the sun shining so brilliantly, the Cenotaph—“like the gnomon of a giant sundial”3—had cast a long and deep shadow. Building further on this image, one might say the shadow cast by the memory of the First World War fell on more than just the crowds gathered on Whitehall that day: it darkened the British twentieth century as a whole.4 Rather uniquely among the countries of Western Europe, the First World War haunted the corridors of national memory in England for at least five decades, leaving its traces in, among many other areas, the attitudes toward subsequent commemoration. In the 1920s, almost every city and town across England had erected its own monuments and memorials to the war dead. The “Great War,” after all, was supposed to have been “the war to end all wars”—a determination that would be safeguarded by the nearly ubiquitous presence of memorial reminders. But while these monuments had helped recall the fallen, they had proven entirely impotent at preventing future conflict. The peace won at such staggering costs had lasted barely two decades.

Small wonder then that by 1944, when a national survey solicited opinions on preferred styles of commemoration for the more recently fallen of the Second World War, opinion had turned bitterly against the prospect of what the anonymous respondents dubbed “useless monuments” and “stone monstrosities on every street corner and village green.”5 Existing monuments would simply need to perform double duty. And so as with the Cenotaph, a similar retrofitting was applied to the monuments in town centers across the country.6 There were of course sites at which the Second World War was explicitly commemorated on its own terms, but in these places commemorative gestures typically took on a far more utilitarian and practical guise in the form of memorial libraries, parks, and other green spaces.7 When viewed through the prism of today’s sensibilities, some of these commemorative gestures seem almost shockingly modest.8 In memory of the fallen of the Second World War, some churches chose to install new lighting. One church in Lancashire honored its recent war dead with a memorial bookcase; another church in Hampshire unveiled a Second World War memorial notice board. A plaque announcing new memorial railings at St. James Church in Higher Broughton, Salford, reflects just how anti-monumental and utilitarian these memorial gestures had become.9

While the Second World War in England occasioned these new churchyard railings, the First World War refused to be confined, maintaining its dominant grip on popular memory until decades later. As late as 1965, the poet Ted Hughes, writing in The Listener, called it “our number one national ghost,”10 explaining that “the First World War goes on getting stronger . . . it’s still everywhere, molesting everybody. . . . And somewhere in the nervous system of each survivor the underworld of perpetual Somme rages on.” Hughes would know. His own father had enlisted in the Lancashire Fusiliers and returned from France a haunted man. “We are the children of ghosts / And these are the towns of ghosts,” Hughes once wrote.11

The First World War’s outsize place in British cultural memory was to a certain extent a sui generis phenomenon. For the United States, it was the Second World War that quickly assumed mythic status as “the Good War” fought by the members of “the Greatest Generation”; likewise in the Soviet Union, the Second World War was cast as “the Great Patriotic War,” an epic and victorious struggle against fascism. Historians attempting to fathom the tenacity of the U.K.’s national ghost often point to the stark differential in casualty numbers between the two world wars. The British death toll in the First World War was extremely high (886,000 military personnel12) with almost every family knowing at least one soldier who did not return; the number of British who died in the Second World War, even factoring in civilians killed during the Blitz, totaled barely one-half of its predecessor. What’s more, the earlier losses hit the upper echelons of British society with particular force, a fact that contributed to the notion of a generation’s future leaders being cut down in their prime. There was also the sheer cultural shock of the First World War’s unprecedented brutality and mass killing. When war broke out in 1914, as one historian has noted, “no man in the prime of his life knew what war was like.13 All imagined that it would be an affair of great marches and great battles, quickly decided.” The enormous gap between these gentlemanly prewar expectations and the shocking reality of battlefield carnage can be sensed in soldiers’ diaries and letters, which also attest to a level of gore that makes even the most graphic of today’s cinematic depictions seem sanitized and tame. All of it added up to a collective trauma that simply could not be assimilated, or as Hughes again put it eloquently, “Four years was not long enough, nor Edwardian and Georgian England the right training, nor stunned, somnambulist exhaustion the right condition, for digesting the shock of machine guns, armies of millions, and the plunge into the new dimension, where suddenly and for the first time Adam’s descendants found themselves meaningless.”14

With all of this in mind, one of the enduring mysteries behind Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem begins to seem like not such a mystery after all. At the center of the War Requiem is the voice of the great First World War trench poet Wilfred Owen (1893–1918). Britten interlays Owen’s words within a setting of the Missa pro defunctis, the traditional Latin Mass for the dead. This was not a decision of passing consequence; the Owen poetry, and the war in which he fought and died, form the expressive heart of Britten’s masterwork. But while Owen is undeniably one of the supreme poets of his generation, the question remains: What is he doing in this piece? When Britten set out in 1961 to consecrate a cathedral rebuilt after Nazi bombing, and to memorialize, in the composer’s words, “those of all nations who died in the last war,” why did he feature the poetry of the “wrong” war?15 Part of the answer lies precisely in this history. As we now see, Britten’s approach in the War Requiem embodied one of the defining tendencies of British collective memory in his own era: commemorating the Second World War by commemorating the First ■

* “The mighty convulsions”: Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, trans. Peter Putnam (Vintage Books, 1953), 41–42.

1. As the mourners settled into their places: Details in this description of the ceremony have been drawn from “In Remembrance of Two Wars,” Times (London), Nov. 11, 1946, 4; “Remembrance Day,” Times (London), Nov. 8, 1946, 2; and “Remembrance,” Times (London), Nov. 9, 1946, 5.

2. As one editorial opined: “Remembrance,” Times (London), Nov. 9, 1946, 5.

3. “like the gnomon of a giant sundial”: “In Remembrance of Two Wars.”

4. the shadow cast by the memory: Among the vast literature on twentieth-century British war memory, the works that most substantially informed this chapter’s summary account include Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory (Oxford University Press, 1977); George Mosse, Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars (Oxford University Press, 1990); Jay Winter, Remembering War: The Great War Between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century (Yale University Press, 2006); Cannadine, “War and Death, Grief and Mourning in Modern Britain,” 187–242; Geoff Dyer, The Missing of the Somme (Vintage Books, 2011); Nick Hewitt, “A Sceptical Generation? War Memorials and the Collective Memory of the Second World War in Britain, 1945–2000,” in The Postwar Challenge: Cultural, Social, and Political Change in Western Europe, 1945–58, ed. Dominik Geppert (Oxford University Press, 2003); and Nataliya Danilova, The Politics of War Commemoration in the UK and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

5. “useless monuments”: See Hewitt, “Sceptical Generation?,” 82. The question of memorialization was also taken up at an all-day conference convened in June 1944 by the Royal Society of Arts, which then published its proceedings almost verbatim, or “as fully as paper restrictions permit.” See “Conference on War Memorials,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, June 9, 1944, 322–40.

6. a similar retrofitting: See Danilova, Politics of War Commemoration in the UK and Russia, 55.

7. a far more utilitarian and practical guise: See Cannadine, “War and Death, Grief and Mourning in Modern Britain,” 231–34.

8. some of these commemorative gestures: The Imperial War Museum maintains a detailed register of more than ninety thousand memorials around the U.K. For details of the examples provided here, see WM Reference Nos. 54793 and 40591.

9. A plaque announcing: The dedication on this particular plaque is quoted in Hewitt, “Sceptical Generation?,” 89.

10. “our number one national ghost”: Ted Hughes, “National Ghost,” Listener, Aug. 5, 1965, in Ted Hughes, Winter Pollen: Occasional Prose, ed. William Scammell (Picador, 1995), 70.

11. “We are the children of ghosts”: Ted Hughes, draft of an unpublished poem, quoted in Helen Melody, “Hughes and War,” in Ted Hughes in Context, ed. Terry Gifford (Cambridge University Press, 2018), 231.

12. 886,000 military personnel: National Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. On the generational impacts behind these numbers, see Jay Winter, “Some Aspects of the Demographic Consequences of the First World War in Britain,” Population Studies 30, no. 3 (Nov. 1976): 539–52.

13. “no man in the prime of his life”: A. J. P. Taylor, quoted in ibid.

14. “Four years was not long enough”: Hughes, Winter Pollen, 73.

15. “those of all nations”: Britten to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Feb. 16, 1961, in Britten, Letters from a Life, 5:313.

Read more about Jeremy Eichler Time's Echo at Lit Hub.

For more information, please visit timesecho.com.

Time's Echo: Music, Memory, and the Second World War

Faber, 7 September, 2023

RRP: £25 | 400 pages | ISBN: 978-0571370535

A remarkable and stirring account of how music acts as a witness to history and a medium of cultural memory in the post-Holocaust world.

When it comes to how societies commemorate their own distant dreams and catastrophes, we often think of books, archives, or memorials carved from stone. But in Time's Echo, Jeremy Eichler makes a revelatory case for the power of music as culture's memory, an art form uniquely capable of carrying forward meaning from the past.

Eichler shows how four towering composers - Richard Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg, Benjamin Britten and Dmitri Shostakovich - lived through the era of the Second World War and the Holocaust and later transformed their experiences into deeply moving works of music, scores that carry forward the echoes of lost time. A lyrical narrative full of insight and compassion, this book deepens how we think about the legacies of war, the presence of the past, and the profound possibilities of art in our lives today.

"Profoundly Moving" – Edmund De Waal

"A work of searching scholarship, acute critical observation, philosophical heft, and deep feeling" – Alex Ross

"A rare book: extraordinarily powerful - magisterial, meticulously rich and unexpected, deeply affecting and human" – Philippe Sands

Read more about the history of Airships:

Alexander Rose's ⇲ Empires of the Sky: Zeppelins, Airplanes, and Two Men's Epic Duel to Rule the World

Sir Peter G. Masefield's To Ride the Storm: Story of the Airship R101

Harold G Dick's The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships: Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg

Guillaume de de Syon's ⇲ Zeppelin!: Germany and the Airship, 1900–1939

Ernest A. Johnston's Airship Navigator: One Man's Part in the British Airship Tragedy 1916-1930

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book.

Additional Credit

With thanks to Kate Burton at Faber. Jacket design by John Gall.