Frederick Douglass

The power of photography

Born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey on a plantation in Maryland in the early nineteenth century, the man we know today as Frederick Douglass would rise to become one of the most prominent Americans of his age.

The crucial moment in Douglass's early life arrived when he was about twenty in 1838. On a September day, after a boyhood spent in slavery, he made a dramatic escape. Travelling by rail and then steam ship, he stole away across the Susquehanna River and to safety. After this his journey northward continued. Eventually it took him all the way to Massachusetts, where, under a new name, he began to speak and write in favour of the abolitionist cause.

It was under this name, in 1845 that his autobiographical Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, was published. The book was an immediate bestseller and it made Douglass’s name. ‘You have seen how a man was made a slave’, he wrote, ‘you shall see how a slave was made a man.’

Not yet thirty, Douglass would remain an active political presence for decades to come. Many people during these years would be inspired by his eloquent, forceful speeches that challenged the ingrained racial stereotypes of the time. It is for these that he is chiefly remembered today. But the also another important component of Douglass's political profile. This was his inspired use of photography.

The timing here is instructive. At about the moment that Douglass had been making his escape from Maryland, across the Atlantic Louis Daguerre was making his famous plates of street scenes in Paris. While Douglass was working on the drafts of his autobiography in Massachusetts, the 'Daguerreotype' was being adopted as a new technology in America. By the years of Douglass’s celebrity, in the 1850s, these plates were established as a new art form.

‘Rightly viewed, the whole soul of man is a sort of picture gallery, a grand panorama, in which all the grand facts of the universe, in tracing things of time and things of eternity, are painted. The love of pictures stands first among our passional inclinations, and is among the last to forsake us in our pilgrimage here. In youth it gilds all our Earthly future with bright and glorious visions; and in age, it paves the streets of our paradise with gold, and sets all its opening gates with pearls.’

— Frederick Douglass, Lecture on Pictures, 3 August 1861

While some regarded photography as frivolous, Douglass was enthusiastic. By the 1860s he was arguing that it was every bit as significant an invention as the electromagnetic telegraph.

If by means of the all-pervading electric fluid [Samuel] Morse has coupled his name with the glory of bringing the ends of the earth together, and of converting the world into a whispering gallery’, he argued, ‘Daguerre, by the simple but all-abounding sunlight, has converted the planet into a picture gallery.

By the time Douglass wrote these words, different ‘types’ of photography were developing. As well as the original Daguerreotypes, there were also 'ambrotypes' and 'electrotypes' and scores of other experimental processes. Enthusiasts like Douglass could buy such things from the growing number of ‘Daguerrean Galleries’, early versions of photography stores.

Douglass liked the democratic quality of photography. In a famous address, Lecture on Pictures, given on 3 December 1861 in Boston, he pointed out:

Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them. What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within the reach of all. The humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty, with all its precious treasures, could purpose fifty years ago.

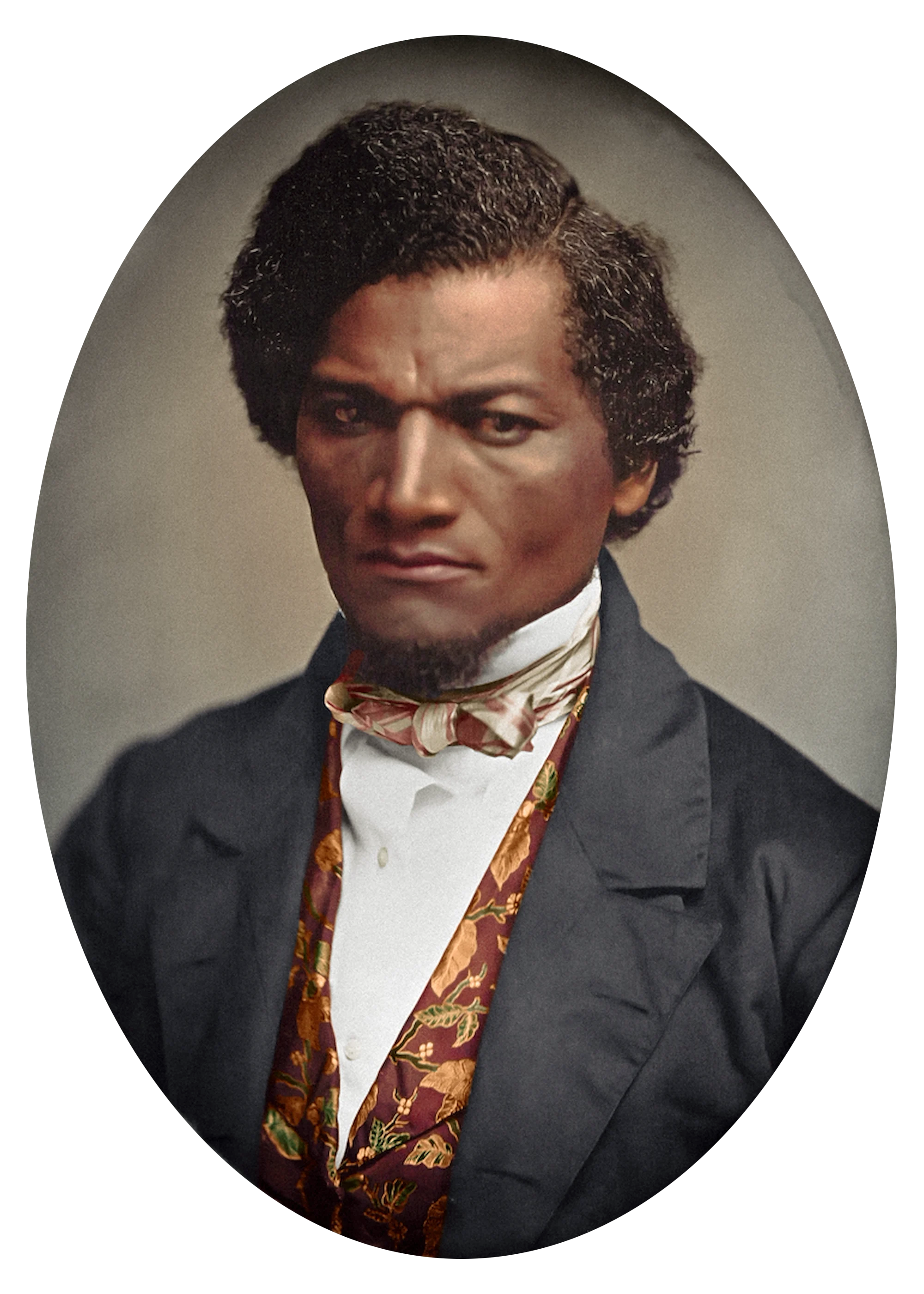

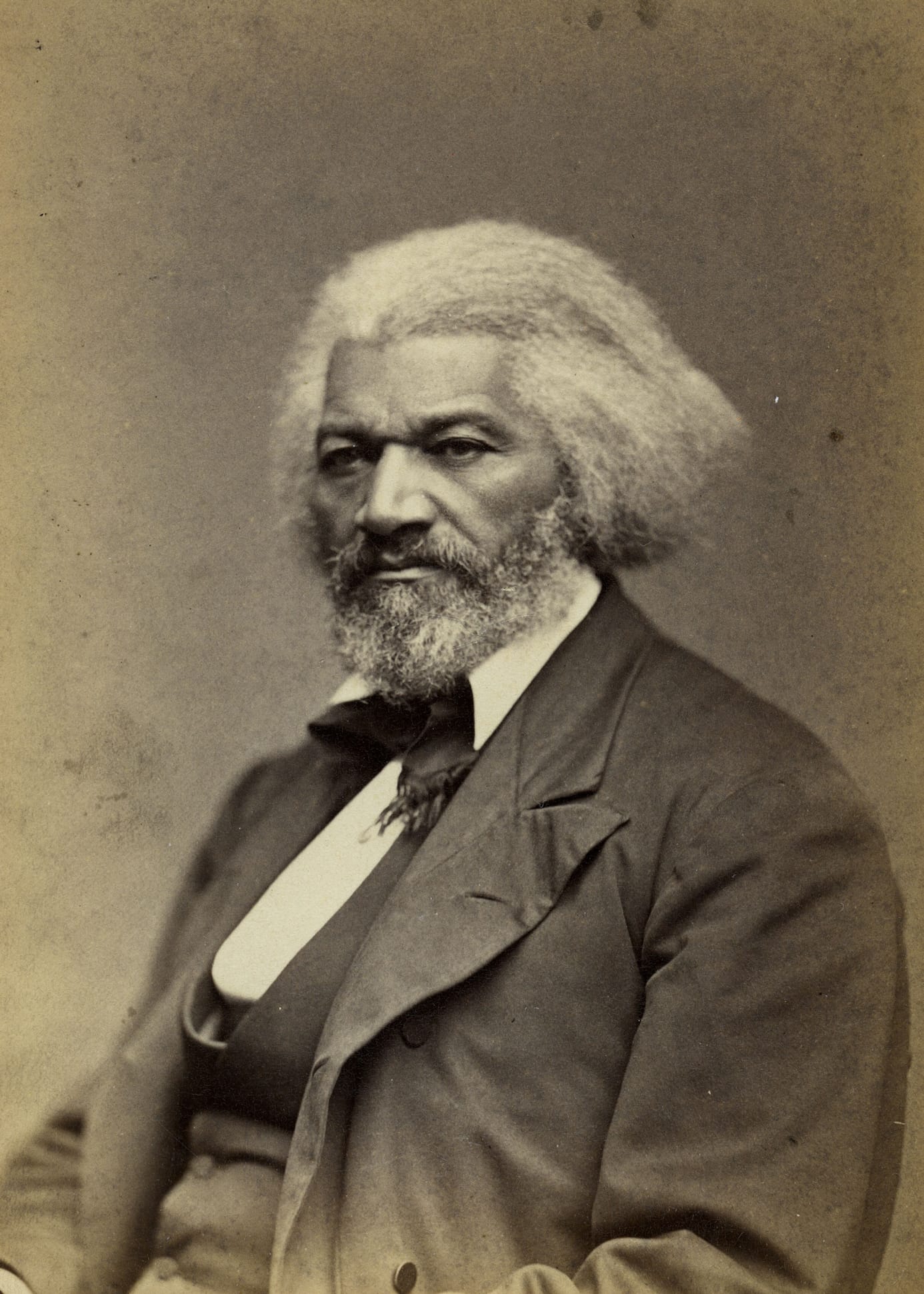

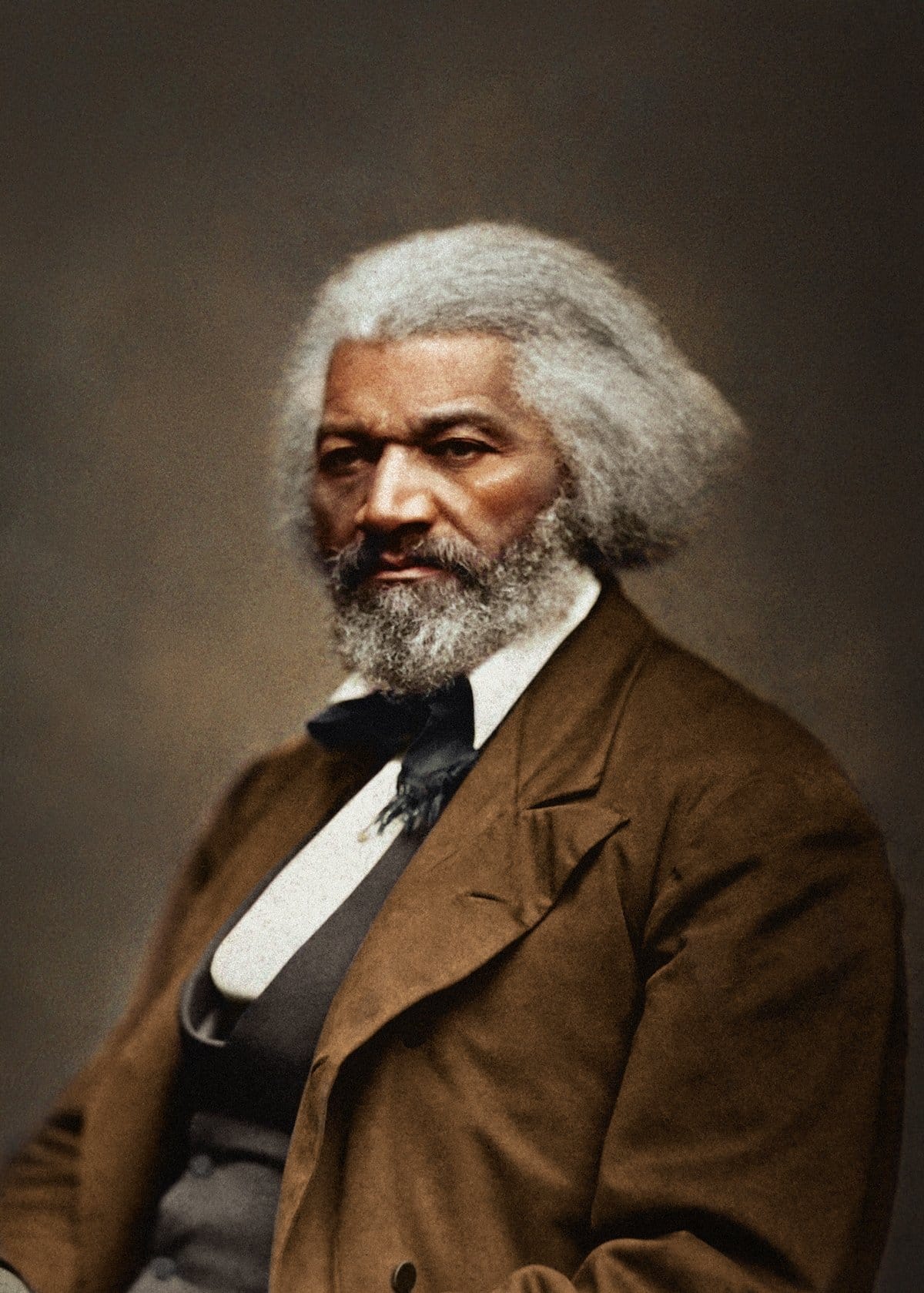

All of this informed Douglass’s own use of photography. He sensed that as well as being an art form, it could also be a political tool. Visual representations of black people had long two dimensional, relying mostly on simplified and prejudiced caricatures. Douglass used photography to present a different image. He sat for many portraits. Each time he dressed himself elegantly, chose not to smile and instead took care to project an image of power and control.

The earliest known photograph of Douglass was made in 1841, just three years after his escape from Maryland. More than 150 others followed over the decades that followed, a number that makes him by common consensus, the most photographed American of the nineteenth century.

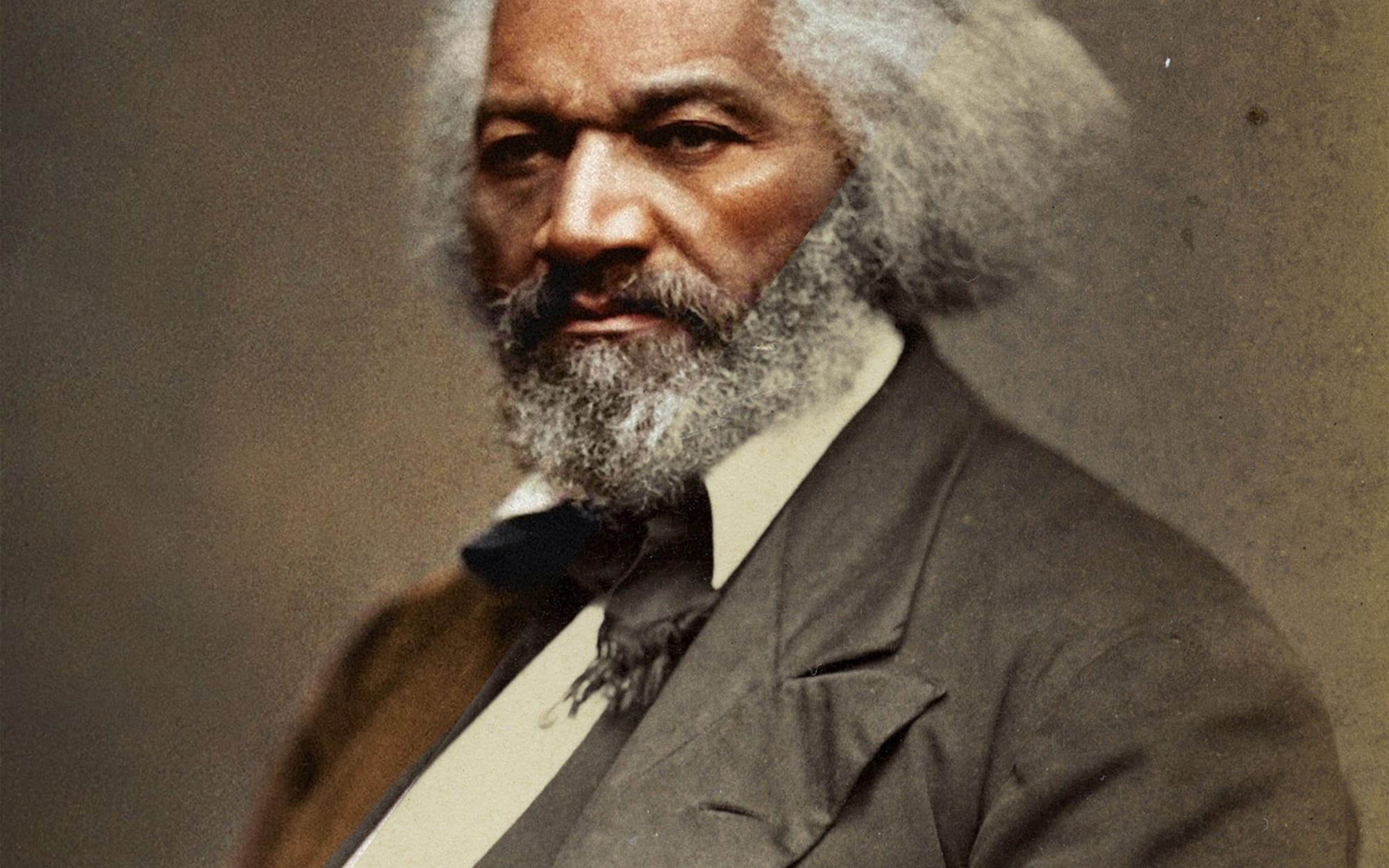

Frederick Douglass, taken approximately 1879, when Douglass was in his early 60s. (⇲ Public Domain) Restoration and colorization Jordan J. Lloyd

This portrait of Douglass was made in 1879. He does not look into the camera, as he so often did, but instead he gazes towards the floor in reflection. His costume is refined, his hair brushed confidently back and he conforms to an almost-Gladstonian image of the dignified, serene public servant.

Douglass’s transformation into colour reveals some details for the first time. The image also feels appropriate. We know that he approved of new technology; he understood the power of the image and he sought to harness it.

In his Lecture on Pictures, too, Douglass memorably pondered the sensation of ‘stern serenity’ that photographs evoked.

Byron says a man always looks dead when his Biography is written. The same is even more true when his picture is taken. There is even something statue-like about such men. See them when or where you will, and unless they are totally off guard, they are either serenely sitting or rigidly standing in what they fancy their best attitude for a picture ■

DeNeen L. Brown, ⇲ The Photos of Frederick Douglass that helped him fight to end slavery, The Washington Post

Frederick Douglass, ⇲ Lecture on Pictures

Caroline Douglas, ⇲ Pictures and progress? Frederick Douglass and early Scottish photography, V&A

⇲ Frederick Douglass and the Power of Photography, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

Kara Hanson, ⇲ How Frederick Douglass Found Power in Photography, Medium

Pamela K. Johnson, ⇲ Frederick Douglass Was the Most Photographed American of the 19th Century, NBC News

Melissa Lindberg, ⇲ Frederick Douglass and the Power of Pictures, the Library of Congress