From the Boy Who Never Grew Up to the Woman Who Lived with the Dead

An exclusive extract from 'Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian London' by Judith Flanders

Judith Flanders is well known for her meticulously researched social histories of Victorian Britain. In her new book, Rites of Passage, she turns her attention on the period's peculiar obsession with dying.

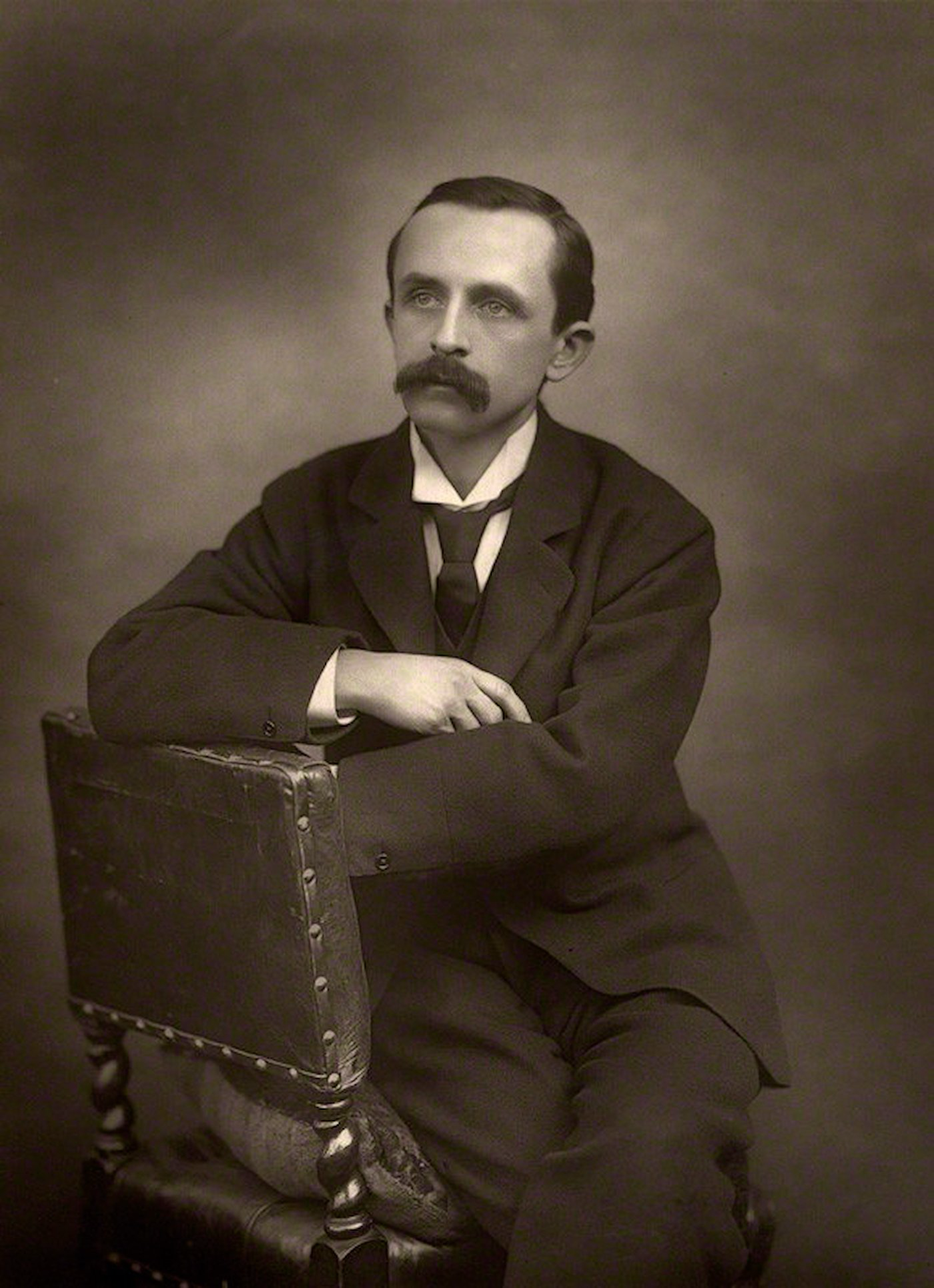

In this extract from the book, Flanders focusses on two instructive stories. The first is of 'Peter Pan', J.M Barrie's ethereal creation, who glides through the London skies and leaves us with many hints about the concerns of the age.

The second story belongs to the figure who gave her name to the era. Queen Victoria's life, explains Flanders, especially after the loss of her husband Albert, became very much about death.

For full references and notes please consult the published book

In 1904, a boy flew into a West End theatre, a child who embodied many of the ideas around death and dying. His name was Peter Pan, ‘the boy who never grew up’. How we look at Peter Pan today, from his later incarnations and how he was understood by his contemporaries, is one way of understanding how our attitudes to death, and to life, have altered. For us, he is the epitome of childhood innocence and freedom, the incarnation of endless possibility as he spends his days playing and doing whatever he chooses in the moment. It is less certain that this was always the case.

J.M. Barrie (1860–1937) produced his first version of Peter Pan in 1902, in a novel called The Little White Bird. That Peter is a baby, only seven days old, who, ‘like all infants’, can fly. He flies out of his nursery and ends up in Kensington Gardens, where he decides to live with the fairies who come out at night after the gates are locked. In his next incarnation, in the theatre two years later, Barrie produced a Peter who was somewhat older, perhaps reaching pre-pubescence, although he gives no firm details.

In his third outing, in a novel Barrie published in 1911, Peter still has all his milk teeth, and so must be around five or six years old. That Peter is described as wearing clothes made out of skeleton leaves, but all three Peters are bringers of death: like an epidemic, The Boy Who Never Grew Up scythes his way through the nursery of the Darling family. Peter’s visits leave empty beds behind for devastated parents to find after their children have flown off to Neverland, the place where babies who fall out of their prams end up, together with those older children who wandered away while their nannies were not paying attention, none of them ever to be seen again. Clothes made from skeleton leaves, vanished children, empty beds and prams – the adventures in Neverland are adventures in the afterworld, because what is death, asks Peter, but ‘an awfully big adventure’?

Peter Pan is death personified, because the only children who never grow up are children who are dead. There were tens, if not hundreds, of thousands who had experienced the death of a child who would have agreed that a dead child was a permanent child.

J.M. Barrie knew this at first hand. When he was six, his fourteen-year-old brother died in a skating accident, a loss from which his mother never recovered. The child Barrie attempted to fill his brother’s place for her by wearing his older brother’s clothes and mimicking his voice in her hearing; she in turn found comfort that her dead son, like Peter, would never grow up, never lose his innocence, would always be a child in her mind.

By the time of Peter Pan’s appearance in theatres, the public was well accustomed to thinking about eternal life. Apart from their individual concerns with death and its accompaniments, the arts had become obsessed with the dead and the undead.

Every bit as popular as Dracula was the adventure-writer H. Rider Haggard’s She, published in 1886/7. This was a wildly successful novel of jingoist imperial adventures in Africa, one that sold an average of a million copies a year for the next three-quarters of a century. In it, a trio of Englishmen follow a series of cryptic clues from Cambridge to Africa, where they are taken captive by a local tribe under the rule of a 2,000-year-old queen. This immortal ruler is Ayesha, the ‘She’ of the book’s title, who lives in a tomb, sleeping beside the embalmed corpse of her one true love whom she murdered in a fit of jealousy 2,000 years before. When the Englishmen are brought into her presence she sees in one of them the reincarnation of this lost love.

Enchanted with his looks, and enchanting him in turn, she brings him to the Pillar of Fire that rendered her immortal, so that he can remain with her for all eternity. To allay his fears over this awful trial, she enters the fire first, but a second immersion destroys her, transforming her first into the 2,000-year-old woman she actually is, before she crumbles to dust.

So far, so far-fetched. But the modern reader might ask if Haggard drew on a person closer to home. By the time of publication Queen Victoria had reigned, if not for 2,000 years, for half a century, having ascended the throne two decades before Haggard’s birth. Victoria, as is well known, mourned her lost husband from his early death at the age of forty-two, in 1861, until her own in 1901. She mourned ostentatiously, withdrawing from public life for five years, forever after dressing entirely in black and carrying out her duties grudgingly. ‘She was their Queen, but she appeared very rarely, perhaps once in two or three years’: is this a description of Ayesha or Victoria?

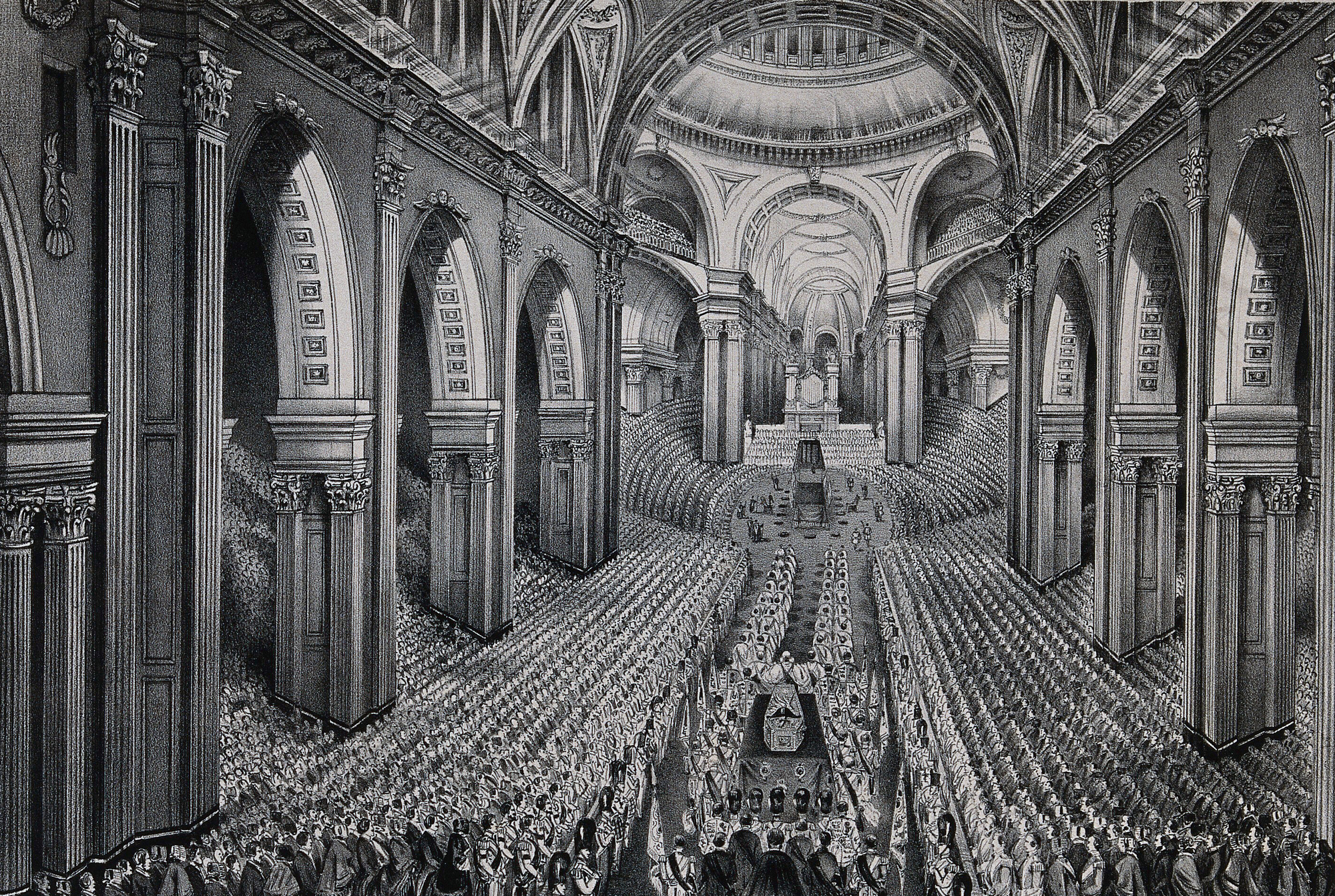

The eternal, the immortal queen, in perpetual mourning. Victoria, like many in the nineteenth century that we have read about, found solace in thinking and reading about those she had lost. She also found the paraphernalia surrounding death to be a comfort. She and Albert had been the driving forces behind the elevation of the Duke of Wellington’s funeral from a grand state occasion to the over-orchestrated orgy of pomp it became.

Victoria herself had wanted the entire army to go into mourning. Not court mourning, nor complimentary mourning. Victoria wanted the army to be reclothed as if they had lost a member of their own family.

After the funeral she wrote to her uncle, Leopold I of the Belgians, ‘how very touching’ it had all been. ‘What a deep and whemtühige [a misspelling of wehmütige, poignant] impression it made on me! It was a beautiful sight! In the Cathedral it was more touching still!’ (That she was not present in the cathedral seems not to have dimmed her conviction, much less her enthusiasm.)

It was not only funerals she enjoyed. Like many of her subjects, she was passionately interested in the medical details of her family’s last days, asking in 1837 for the ‘painfully interesting’ details of the final illness of William IV. In 1860, she and Albert visited Albert’s childhood home in Coburg to view the mausoleum he and his brother had designed for their father in the 1840s. She found it ‘cheerful’, and commissioned a summerhouse that resembled the mausoleum for her mother, as well as planning a second one for her own family’s use.

After her mother’s death in 1861, she and Albert read the Reverend William Branks’ Heaven Our Home together. This very successful book had been published a few months before, and achieved great popularity with the reading public, promising as it did that all would ultimately meet in the ‘eternal home of love’, where we would ‘recognise’ our friends and family.

Until then, Branks assured his readers that the dead kept up a ‘deep and glowing and unquenchable interest’ in the activities of the living. (The good clergyman appeared to enjoy italics as much as the queen did.) Certainly, her mother’s death was not easy for Victoria. Mother and daughter had had periods of estrangement, and feelings of guilt provoked a deep depression in the already depressively inclined queen. She refused to join her family for meals, staying in her rooms alone. She went out only to attend ceremonies to mark events in her mother’s life, such as a memorial birthday.

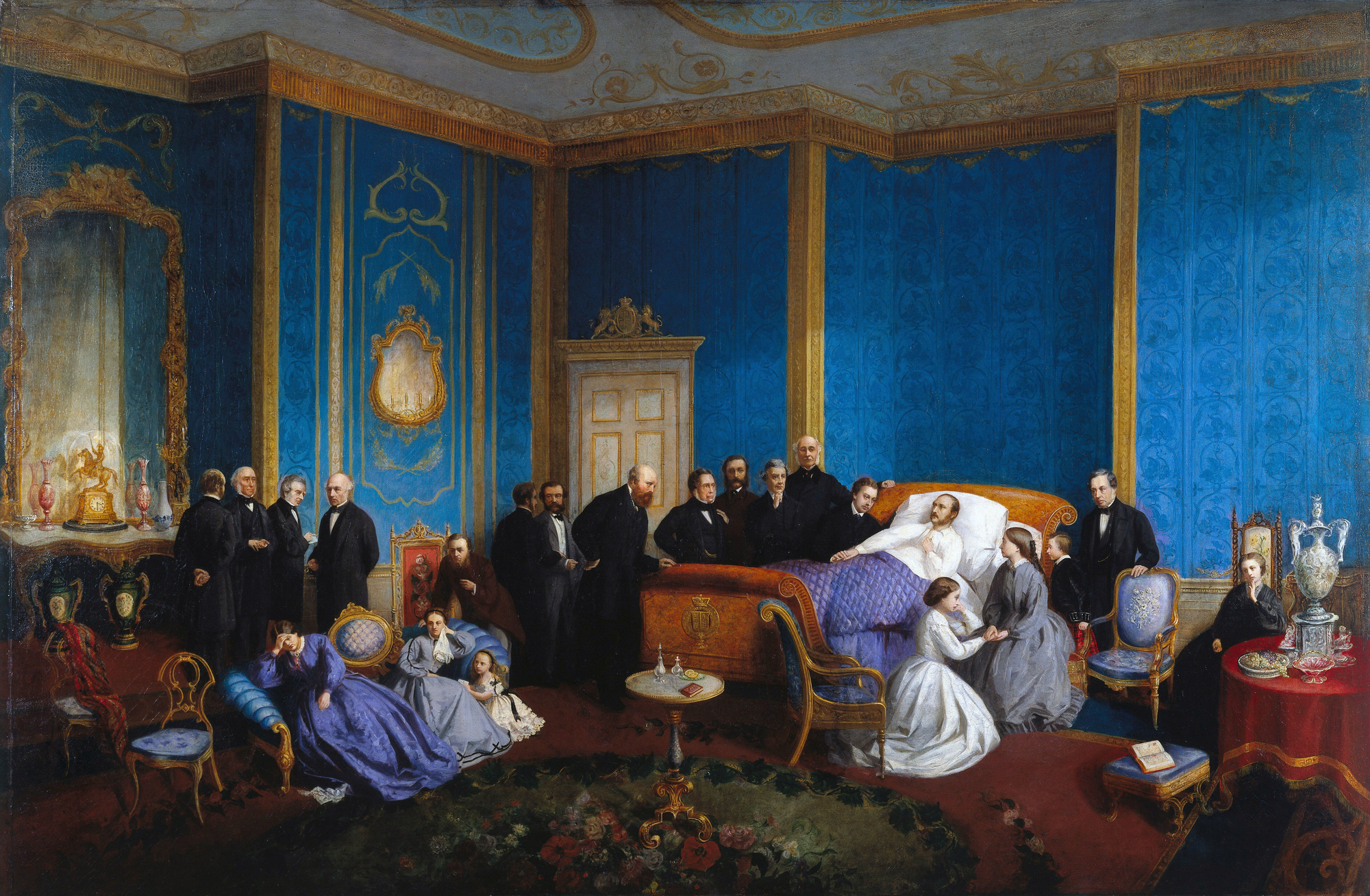

Thus, when her own husband died nine months later, she was entirely overcome and unable to function. Albert had been ailing for at least two years, and was visibly ill to everyone except the queen, who steadfastly refused to believe in the seriousness of his chronic stomach trouble. In December 1861 he became bedridden, and the doctors pronounced typhoid fever. For much of his final illness, the queen continued to believe he would recover, and so his death, when it came on 14 December 1861, was not merely a great loss – it was also a great shock.

Her religion became Albert worship. She began to use capital letters for pronouns when writing of him (Him). She had casts made of Albert’s hands and face after his death, and referred to them as ‘sacred relics’.

The depression she had suffered nine months before was nothing compared to her current state. She told her family and ministers that she was as good as dead. She required the deepest mourning for the court. She withdrew physically from all (except some of) her children, notably excluding Bertie, the Prince of Wales, for whom she had never felt much affection, repeating the Hanoverian pattern of terrible relations between monarch and heir.

She decided that Bertie had caused his father’s death, either through the (unlikely) possibility that Albert had caught typhoid on a trip to see Bertie to upbraid him for a recent escapade of lax, possibly immoral behaviour, or that that behaviour had caused Albert so much anxiety that he had been unable to rally from an otherwise survivable illness (even less likely). She disregarded all matters of state; she refused for years afterwards to perform the most basic of her duties, such as presiding at the state opening of parliament.

For the first decade after Albert’s death she was, at best, undergoing a major psychological breakdown. Her physician, William Jenner, as late as 1871 thought that what were referred to as her ‘nerves’ – which expressed themselves as bouts of hysterical weeping, fits of rage and intermittent panic – ‘were a form of madness’.

Her religion became Albert worship. She began to use capital letters for pronouns when writing of him (Him). She had casts made of Albert’s hands and face after his death, and referred to them as ‘sacred relics’. She had post-mortem photographs taken and attached to the head of her bed in each of her bedrooms, so that she would lie beneath his image, almost as if it were a religious icon.

One of the many portraits of him that she commissioned had the prince receiving a halo in place of his earthly crown (which, to her fury, he had never achieved, as she had never been able to talk the government into raising him from a prince consort to a king). She began the construction of a mausoleum at Frogmore, in the grounds of Windsor Castle, and efficiently ordered an effigy of herself at the same time, so that on her own death the couple would be aligned in age and style, remaining a matched set. When the mausoleum was complete, she used the verb ‘translate’ when talking about moving Albert’s remains to it, a word more commonly used to refer to moving the relics of a saint.

Victoria also established a secular shrine, one that supposed that the definitely dead man continued to be alive. It is commonly said that the queen had ordered Albert’s bedroom to be preserved exactly as it had been in his lifetime, with the clock and his watch kept wound, hot shaving water brought up daily, his clothes laid out several times a day for him to change into, his gloves set out on the table as if he had just stepped in from outdoors. However, Albert had not died in his own bedroom. In his final illness he had frequently been delirious and he wandered at night from room to room, happening on his final walk to end up in the room where both George IV and William IV had died.

This suited the queen’s need to mythologize, and, having been unable to persuade the country or her ministers to make Albert a king, she could present to the court the status she had desired for him by virtue of his dying in the room where past kings had died. Even so, the decor was given additional elements of homage: regularly refreshed mourning wreaths were laid out on the beds; a portrait bust of Albert was installed; his personal items were transferred from his dressing room and laid out as if for use, even as new washstand china was ordered for the dead man’s ablutions.

Today it is often assumed that Queen Victoria’s prolonged grieving was characteristic of the age and was considered admirable by her contemporaries. Neither of these statements is true. Her adoption of perpetual mourning dress was a choice made by many widows, but certainly not by all.

The wife of a textile manufacturer whose husband died in the year of Victoria’s accession wore black for a number of years, as was customary, and then turned to fabrics that included ‘white embroidered muslins . . . blue-and-white striped silk, [and] purple-checked cotton and gold damask’: hardly our conception of a nineteenth-century widow.

Victoria was stubborn in her grief, however. Those concerned with matters of state thought that she was using her loss as an excuse to do exactly what she wanted to do, and to not do whatever she did not want to do. At least in part, the queen herself knew this, as the confused reasoning in a letter she wrote to Lord Russell, the prime minister, shows. Five years after Albert’s death, she continued to refuse to attend the state opening of parliament. She wrote, referring to herself in the third person, as was her custom: ‘That the public should wish to see her she fully understands, and has no wish to prevent – quite the contrary; but why this wish should be of so unreasonable and unfeeling a nature, as to long to witness the spectacle of a poor, broken-hearted widow . . . dragged in deep mourning, alone in State as a Show . . . to be gazed at without delicacy of feeling, is a thing that she can’t understand.’

As far as it can be untangled, Victoria was saying she could entirely understand the reasonable desire of the people that she should attend to matters of state, even as she could not understand how they could be so unreasonable as to expect her to attend to matters of state.

Alexandra of Denmark, engaged to the Prince of Wales, arrived in Britain some fifteen months after Albert’s death. Victoria felt that a festive greeting from a mourning populace would be unseemly, and so sent a coach for her entry into London that was so old and shabby her ministers were ashamed. (Another even less generous, but still plausible, interpretation of the gesture was that she did not want the arrival of the last royal fiancé, Albert himself more than two decades previously, to be overshadowed.)

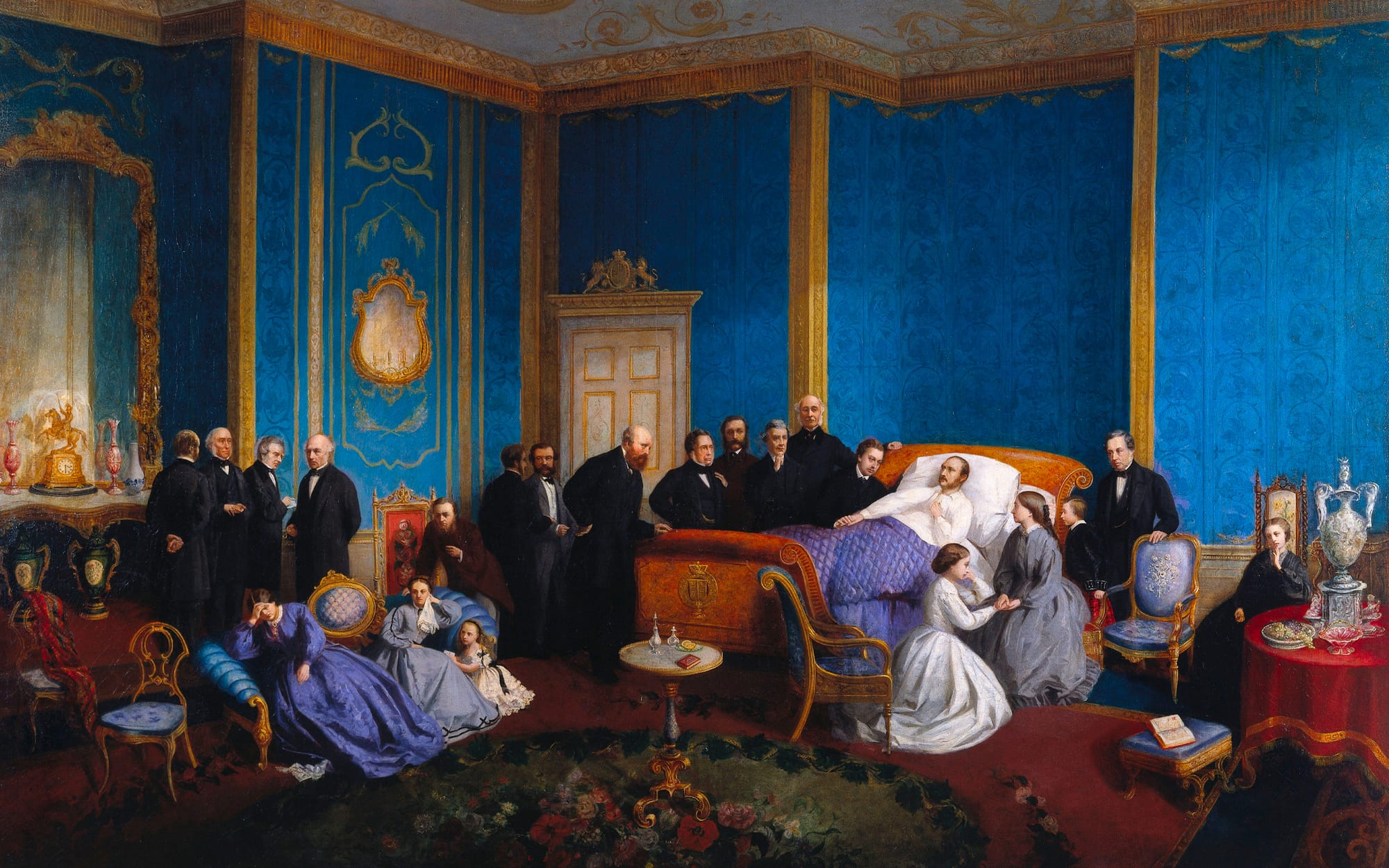

At the wedding, held at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, instead of Westminster Abbey, to accommodate the queen’s mourning, Victoria refused to doff her widow’s weeds for the ceremony as custom and etiquette dictated, nor would she join the wedding party, but sequestered herself in the Royal Closet above the altar, like a ghost at the feast, faithfully replicated by the artist William Powell Frith.

She also decreed that none of her children should divest themselves of their mourning, also against custom, and insisted that not only should they wear halfmourning, but that they should wear it for another full year – three years after their father’s death – before extending that later to five years for some of her daughters.

Even more gloom-laden was the official portrait taken of the sovereign with the newly wedded heir to the throne and his bride. Instead of a standard photograph of the happy couple, the queen drew on the tradition of mourning photographs where the bereaved hold pictures of their lost loved ones. Bertie and Alexandra stand, looking rather nonplussed, neither touching nor looking at each other, with the queen between them but ostentatiously turned away from both to stare grimly at a bust of the groom’s dead father, her lost beloved. Jane Carlyle, the wife of the philosopher Thomas Carlyle, spoke for many of the population when she wrote that she sympathized with the new Princess of Wales ‘in the prospect of the bother she will have by and by with that mean-natured, half distracted Queen’.

.jpg?auto=webp)

Others who had undergone similar, or far worse, losses were no more sympathetic. Mrs Oliphant. a popular novelist, who had seen her husband and all of her children die, wrote, some quarter-century after Albert’s death: ‘I doubt whether nous autres poor women who have had to fight with the world all alone without much sympathy from anybody, can quite enter into the “unprecedented” character of the Queen’s sufferings. A woman is surely a poor creature if with a large, happy affectionate family of children around her she can’t take heart to do her duty whether she likes it or not. We have to do it, with very little solace, and I don’t see that there is anybody particularly sorry for us.’

But Victoria could not ‘take heart to do her duty’. Instead she channelled Albert, becoming the sole conduit for what he would have said, done or wanted. Before the marriage of the Prince of Wales, she took the couple to his tomb and said, ‘He gives you his blessing’, joining their hands over his grave. She also participated in the contemporary pastimes of table-turning, rapping and other spiritualist practices.

But the currency of Albert worship was most visibly expressed through objects. Victoria had always had an intense connection to her own possessions, which became more extreme after she was widowed. Unlike most women of the time, she neither gave away her old clothes nor had them refashioned, but instead stored what ultimately turned out to be nearly seventy years’ worth of items. She kept her childhood china, and her children’s childhood china. She kept her children’s baby teeth, which she had turned into jewellery. (The infant Beatrice’s milk teeth make the stamens of earrings and a pendant designed to look like fuchsia.)

More than that, she ordered that ‘Every piece of plate and china, every picture, chair, table ornament and articles of the most trivial description’ be photographed from multiple angles, the photographs then bound up in ledgers which she liked to look over several times a week. Notes were made of the date each object was acquired, how and by whom, and where it was located.

Once something was in place, it was not allowed to be moved: that was where it belonged for evermore, as if by cataloguing and freezing her possessions in time, she could control the world around her. All the rooms in her residences had small cards at the thresholds, noting that everything in that particular room had been selected and arranged by Albert. Hangings, curtains, carpets and other textiles were copied, so that when they wore out or faded, they could be replaced without any discernible change.

As many people did, the queen had numerous pieces of her husband’s hair made into jewellery, of which nearly a dozen pieces are known. She also commissioned portraits for lockets and other jewellery, as well as copies of the casts of Albert’s face and arm, and portrait busts, to be given away to friends, family and government ministers.

Initially Victoria had had an ambivalent relationship with some of the objects, refusing to look at the death mask made immediately after Albert’s death, even as she would not ‘allow the sacred cast . . . to go out of the house’.

She wore other pieces, such as the bracelet containing Albert’s portrait and his hair, every day. More than thirty years after his death the bracelet one day snapped, and despite a jeweller being summoned immediately, in the few hours before it was repaired and back on her wrist, recorded one observer, she remained in a heightened state of ‘unhappiness and anxiety’.

These memorial lockets and jewels were a continuation of the virtual shrines that were her own suites of rooms in each of her residences. An anonymous member of the royal household described them in the 1890s. The queen’s Windsor sitting room contained a life-sized portrait of Albert by one of her favourite painters, Franz Xaver Winterhalter; another by sentimental favourite Sir Edwin Landseer, with the prince dressed in shooting costume; a ‘little’ picture of him with his brother, and a portrait of him in historical costume for a fancy-dress ball. In her bedroom there were two portraits of the dead prince as a child, a sketch of the queen ‘garbed as a nun’ receiving a vision of Albert, a portrait of Victoria’s mother, as well as ‘a pictorial recollection of her [mother’s] room, and the sofa on which she died’.

There were, says this report, 231 portraits in the queen’s private rooms, none of which depicted her daughters-in-law, her sons-in-law or her grandchildren. Other residences contained life-sized statues of Albert before which fresh wreaths were laid ceremonially on the queen’s orders, including one in the grounds of Balmoral, where ‘her family and Court, her servants and tenantry’ gathered on the prince’s birthday every year. Victoria enjoyed marking commemorative days: Albert’s birthday; his death day, which she spent in total seclusion; her mother’s birthday and death day; and so on. Until her own death, she remained consumed by the minutiae of mourning: state papers were returned unsigned if the black border on them was not sufficiently wide, while as late as 1897 her maids of honour were forbidden to wear mauve, a very ordinary half-mourning colour, because she felt it was too close to pink, the cheerfulness of which she decreed to be unseemly.

The queen’s death fixation was not solely focused around Albert, her mother or even her own family. One of her ladies-in-waiting wrote that she took ‘the keenest interest in death and all its horrors, our whole talk has been of coffins and winding sheets’. She enjoyed discussing the funeral of a servant (‘overdone’, remarked the lady-in-waiting, and ‘very trying for the Household’). At Balmoral she went to lay a wreath on the tomb of her old dresser. It was not even necessary that she have any acquaintance with the dead. One holiday in France saw her attending the funeral of a soldier who had died of consumption while she was staying nearby. ‘[T]he Queen really enjoys these melancholy entertainments,’ wrote a bystander.

Victoria was eighty-one when she died. By dying in January 1901, she could be said to have seen the old ‘Victorian’ century die. She too lay in state, first in her bedroom at Osborne, on the Isle of Wight, where she was viewed by her family and servants. Her son, the new king, did not share her enjoyment of death and death rituals. When his own son had died at birth, thirty years earlier, he said, ‘I think it is one’s duty not to nurse one’s sorrow, however much one may feel it.’22 Now, on the death of the woman whom many had long called ‘the old queen’, sacred pictures and flowers were scattered around her coffin as it was moved from her bedroom to the dining room, from private to public, old style. The family and servants were joined by members of the community, now also with the addition of journalists into the mix.

The age of death, dying and mourning was itself dead. The age of celebrity had arrived, the age of silver-screen death. Now grief and mourning were less and less public, outward-facing community events. Twentieth-century death was to become mechanized – witness the mass slaughter of the killing fields of World War I – but it was also to become a personal, inward emotion, shared only with family or close friends. The ‘old queen’ and her forty years of ostentatious grieving were to be replaced by the twentieth century’s byword, individualism ■

Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain

Picador, 29 February 2024

RRP: £25 | 352 pages | ISBN: 978-1509816972

Through stories from the sickbed to the deathbed, from the correct way to grieve and to give comfort to those grieving to funerals and burials and the reaction of those left behind, Flanders illuminates how living in nineteenth-century Britain was, in so many ways, dictated by dying.

This is an engrossing, deeply researched and, at times, chilling social history of a period plagued by infant death, poverty, disease, and unprecedented change. In elegant, often witty prose, Flanders brings the Victorian way of death vividly to life.

"Nobody knows more about everyday life in Victorian Britain than Judith Flanders." — Douglas Robert-Fairhurst, author of Metamorphosis and The Turning Point

"Flanders writes with sharp intelligence and first-class scholarly attention to detail . . . and rather relishes the swirling gothic atmosphere of her subject, which takes in everything from bodysnatching to suicide, capital punishment to cremation." — The Telegraph

"There is no aspect of Victorian death that does not make it into Judith Flanders’s latest investigation into 19th-century life ... Flanders’s strength has always been to move deftly between micro and macro, the general and the particular, the societal and the entirely personal, to produce that kind of panoramic yet teeming view beloved of the Victorians themselves." — Sunday Times

Additional Credit

With thanks to Caitlin Kirkman