Genghis Khan’s Englishman

Angus Donald pursues a mysterious Englishman who rode with the fearsome Mongol horde

We are accustomed to thinking of Medieval England as a relatively static place, with people kennelled away in their shires and parishes.

But during the time of the Crusades some individuals made remarkable journeys. The chronicler Matthew Paris mentioned one such Englishman who joined the legendary Mongol army in the thirteenth-century.

The facts of this man's life are obscure. But there is enough that remains to ignite the imagination, as the novelist Angus Donald explains.

One morning about five years ago, having breakfast in bed and leafing through The Times (my employer for many years), I came across a column by the veteran commentator Matthew Parris. I can’t remember now what the column was about but, in it, Parris briefly mentioned the legend of an Englishman who had ridden with the Mongols in the 13th century. I sat up too fast and spilled my coffee. It was a lightbulb moment. What a story, I thought. And what a great historical novel that would make.

I began to research my idea in the writings of another Matthew Paris – a well-known 13th-century chronicler-monk based in St Albans, who was mentioned in the Times article, and who in 1243 recorded a bizarre letter sent by a middle-aged priest called Ivo of Narbonne to his boss the Bishop of Bordeaux. The letter was an attempt to persuade the bishop to warn the English, French and Spanish kings about the grave threat that now faced them – and, indeed, all of Christendom – from the war-torn east.

In the first decade of the thirteenth-century, Genghis Khan had united the warring nomadic tribes of the Asian steppe under his banner, calling them all Mongols, binding them to him personally, and building from them a superb, cavalry-based military machine. With it, he conquered China, Persia and all the Central Asian lands between.

By the time the Great Khan died in 1227, his writ had reached the western shores of the Caspian and his generals had conducted a reconnaissance in force around Eastern Europe. A decade later, under his successor Batu Khan, the Mongols invaded the Russian lands, smashed the independent Rus’ dukedoms, expelled the Hungarians from the Pannonian plain and destroyed the massed Polish knights in pitched battle at Legnica in 1241.

The Mongols were kicking at the doors of western Europe and Ivo of Narbonne was trying to rouse the great princes of Europe to this looming catastrophe. In his letter, he says that the Tartars (as he called the Mongols) were bent on world domination and he mentions an Englishman, who was captured just outside Vienna in 1241 riding with a squad of Mongol scouts, as the source of his knowledge about the enemy’s battle ferocity, disgusting cannibalism and all-round barbaric behaviour.

After reading Ivo’s letter (in an 1852 translation of Paris’s work), I became thoroughly intrigued by the Englishman’s strange story. Why was he riding with the Mongols? Father Ivo’s letter offers us only tantalising hints.

The priest from Narbonne says the Englishman had been banished from England for “certain crimes”, which are unspecified, and that he had been recognised by the duke of Austria as the man who had twice come to Pest (now Budapest) as an envoy of the Mongols, helping to translate their demand for the unconditional surrender of the King of Hungary.

The captive Englishman was accused of being a traitor to Christendom – which he denied – but he gave only a limited account of his activities to Ivo. He said that, before he was thirty, he had been at Acre and lost all his possessions at gambling and had left the city in nothing but a shirt of sackcloth. Then he had wandered east in a “shameful state of want and in an enfeebled state of body”.

At length, he found himself “among the Chaldees [ie, in Iraq] and became weary of life”. He learnt many languages on his travels, he says, and was recruited by the Mongols who needed interpreters. They “bound him to be loyal in their service by bestowing on him many gifts”. And that is pretty much all we can glean about the Englishman’s life from Ivo of Narbonne’s letter. We do not even discover his ultimate fate.

However, I was not the only writer to be intrigued by the Englishman’s story. I came across a book published in 1978 by the Hungarian journalist Gabriel Ronay, which examines the Englishman’s story and speculates in a scholarly way about his motives and life story.

The Tartar Khan’s Englishman is an engrossing, imaginative piece of work – and has been slightly pooh-poohed by historians as being too fantastical – but I found it useful in trying to reconstruct the possible travels of the Englishman for a historical fiction novel.

Ronay suggests that the mysterious man was called Robert and was exiled from southern England for taking part in one or more of the various rebellions against King John around the time of Magna Carta. He also claims that he was a Templar, perhaps because of the Acre connection. The city in the Holy Land was a great Templar stronghold at the time. Ronay’s arguments seemed plausible to me.

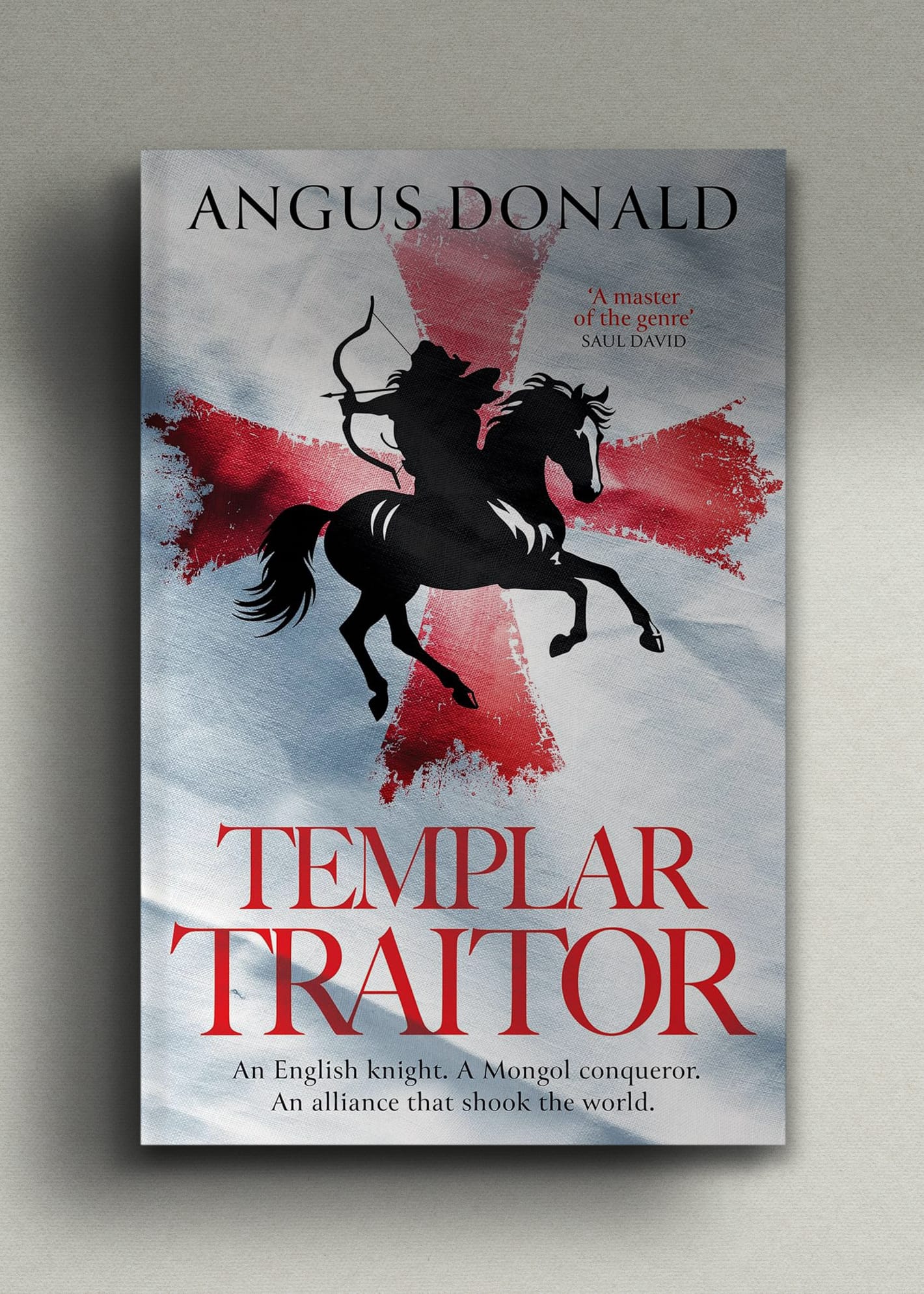

Then I began to construct a storyline for Templar Traitor based on the generally accepted history of both Christendom and the Mongol Empire, Ivo’s letter, and Gabriel Ronay’s intelligent and convincing speculations.

I had three factual points of reference: that Robert was at Acre in 1218 (when he was not yet thirty) during the Fifth Crusade, when the Latin Kingdoms along a thin strip of coast in the Holy Land were fighting for their very existence against the far more powerful Ayyubid Sultanate based in Egypt; that Robert had risen to the high rank of envoy in the Mongol army by the spring of 1241, when he was seen in Pest by the duke of Austria; and that he was with the Mongol scouts when he was captured outside Vienna in the summer of 1241. On this tripod of historical sightings, I balanced my fictional narrative.

I do not want to give too much of my story away because Templar Traitor is a tale steeped in intrigue, misdirection and outright deceit. The novel is framed by Ivo’s interrogation of Robert in a dank prison cell below Vienna Castle. In his chains, the Englishman recounts his life story and involvement with the Mongols over a twenty-year period.

However, from close reading the Ivo letter, it became clear to me that the priest was a rather shady character, who may have acted as an agent provocateur on behalf of his masters to uncover religious crimes.

At the same time, the Englishman also seems to be concealing many of his true actions, distorting the truth either to tell his captors what they wish to hear, or for other more complicated reasons. Part of the fun in reading Templar Traitor is trying to work out who is lying to whom – and why.

But this is also an adventure novel, a tale of war and battle. I made the assumption that Robert joined the Mongol army fairly soon after his departure from Acre in disgrace.

I have him first meeting the Mongols outside the city of Otrar in 1219, on the banks of the Syr Daria in modern-day Kazakhstan, and participating in the siege of that wealthy trading hub on the northern edge of the Khwarazmian Empire. He is swiftly integrated into Genghis Khan’s army and plays a full part in many of the bloody events that followed in the wide Mongol sphere of influence.

This was my historical anchor – the real-life actions of Genghis Khan, his successors and generals as they prosecuted the war against the Persians, the Chinese and others. For this information, I leant heavily on Jack Weatherford’s magisterial Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, and Frank McLynn’s terrific Genghis Khan.

Unfortunately, neither of these historians mentions of the Englishman at all, so I had to invent a great deal for Robert to say and do over the course of the first novel, and will have to do so again in subsequent novels in the series.

However, many of the most prominent people involved in my story are real, and many of the terrible events described actually happened, and the brutally efficient Mongol war machine is as accurately depicted as possible.

The near-invincible armies Genghis Khan commanded were extraordinary for that day and age – and perhaps for any time. And, while we will never know precisely what Robert’s exact role in the Mongol machine was, and what particular battles he took part in, I’m absolutely sure the Englishman’s time in Asia was rarely dull •

This feature was originally published September 10, 2025.

Templar Traitor: An English Knight, A Mongol Conqueror, An Alliance that Shook the World

Canelo, 28 August, 2025

RRP: £10.99 | ISBN: 978-1835980903

“Brimming with action” – Adam Lofthouse, author of Eagle and the Flame

July 1241. Western Europe cowers in terror before the threat of a Mongol invasion. The swift cavalry columns of Genghis Khan have smashed the steel-clad warriors of Russia, Poland and Hungary – and now Austria lies directly in their path.

At a skirmish outside the walls of Vienna, German knights capture a squad of Mongol scouts and are astonished to discover one of their number is an Englishman – a former Templar – who has been riding with these Devil’s horsemen for more than twenty years. Interrogator Father Ivo of Narbonne is summoned to draw the truth from the prisoner before his impending trial, to find out why he abandoned his faith, his Brethren and his homeland to become… a traitor to Christendom.

With thanks to Kate Shepherd.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store