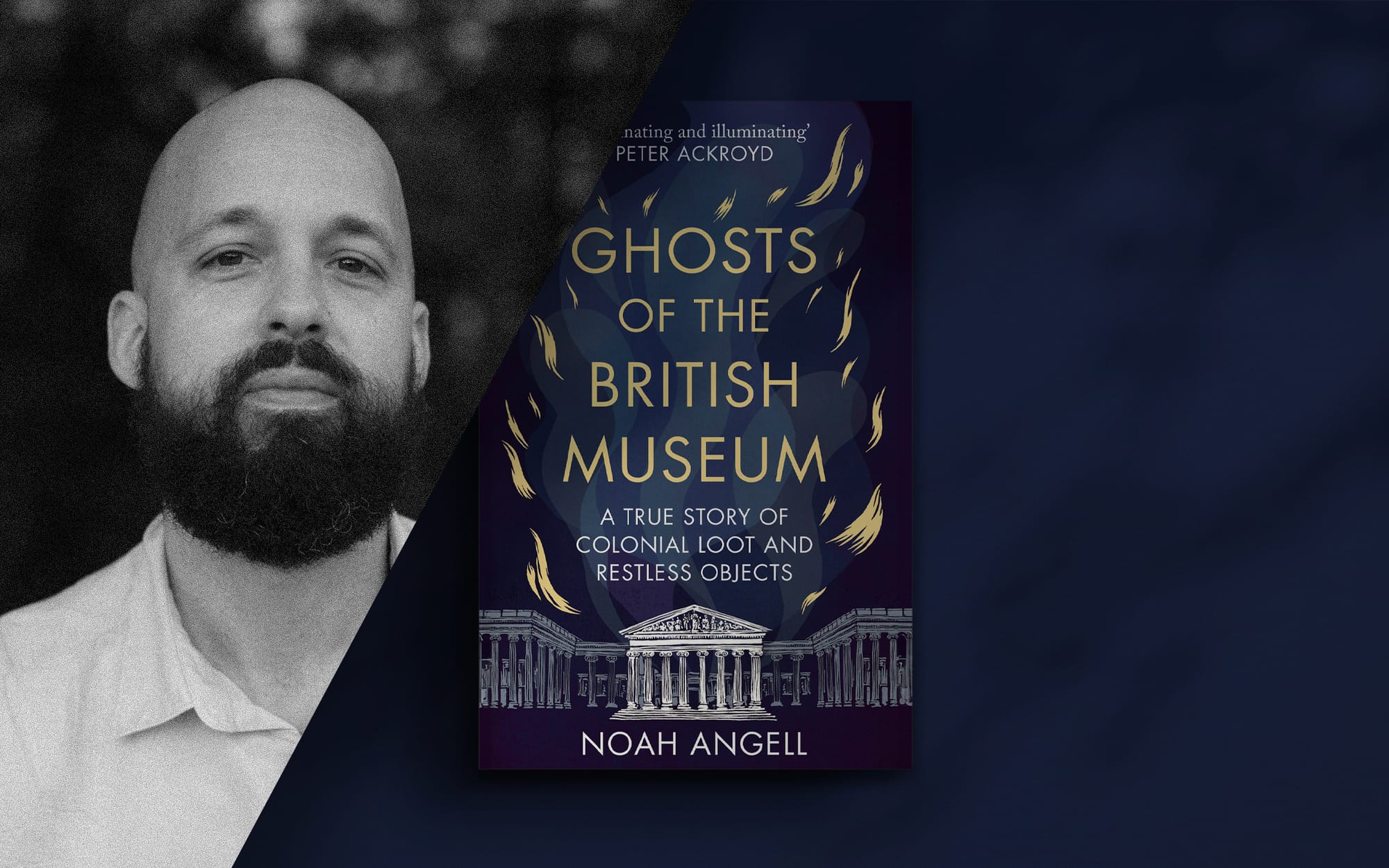

Is the British Museum Haunted? with Noah Angell

Writer Noah Angell on the ghosts of the British Museum

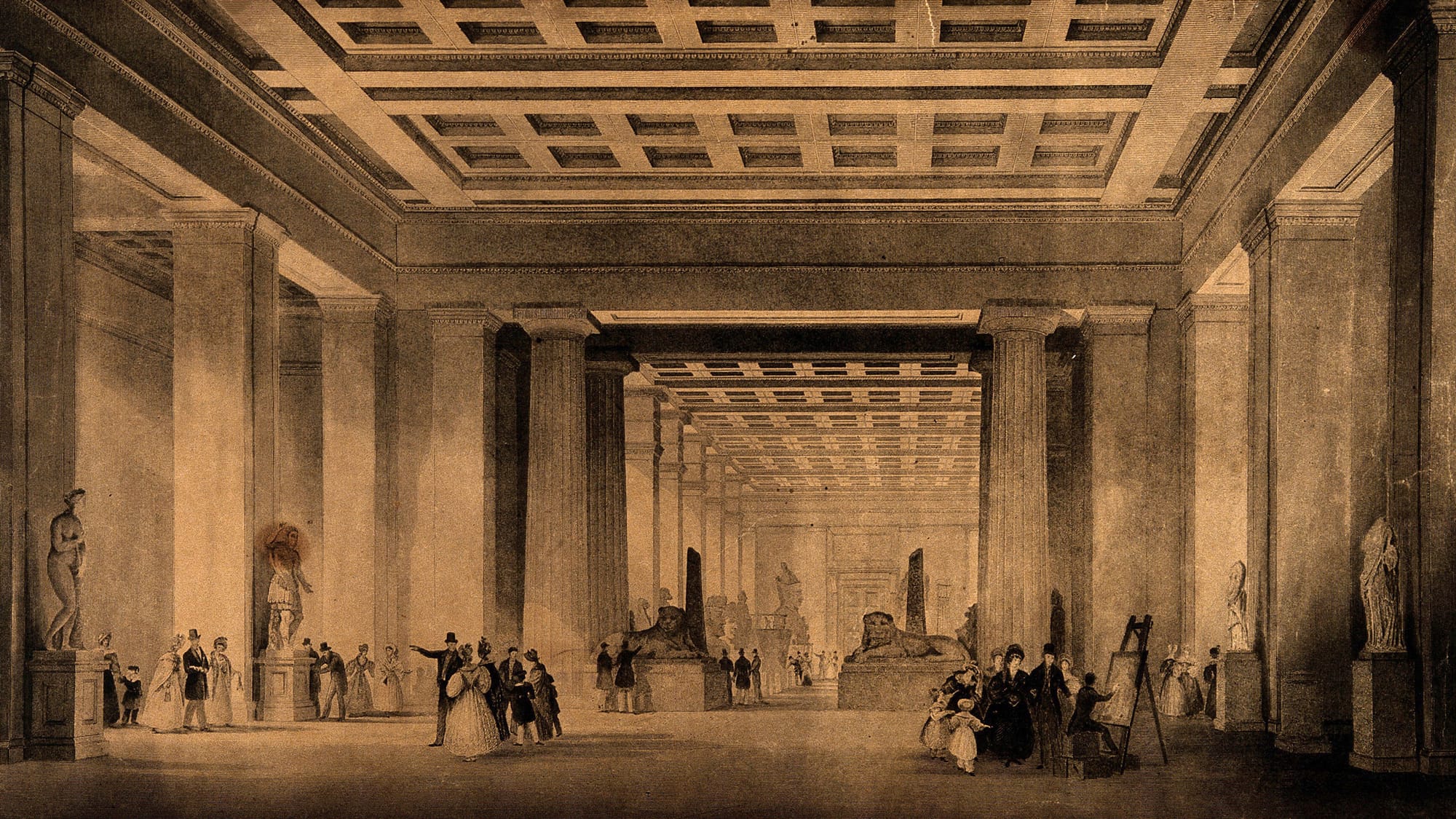

The British Museum is one of Britain's leading cultural institutions. Set in the heart of Bloomsbury in central London, its imposing façade and expansive Great Court project a sense of power and enlightenment.

But the writer Noah Angell explains that beyond this lies a more curious and opaque history. The museum, he discovered through conversations with its staff, is said to be a deeply haunted place filled with restless energy.

In this interview Angell explains more about this intriguing subject, which provides the material for his newly published book: Ghosts of the British Museum.

Unseen Histories

You grew up in North Carolina, a place you describe as being peculiarly haunted. Can you tell us a little about this?

Noah Angell

In Ghosts of the Carolinas by Nancy Roberts, it’s written that '... Surely no section of the nation can rightfully claim more mystifying, more intriguing, more sadly accusing, more altruistic, or more enduring ghosts. Of a certainty we have our share of the finest shades in America.'

This is written as if the ghosts are a natural resource, like the tobacco crop that was being taxed and regulated out of existence at the time of its publication. I have volumes of self-published books of local ghost lore from North Carolina, and many of the spectres who appear in them date from the period of British colonisation onwards — lost and starved settlers; wandering, warring and unperturbed Indigenous people; enslaved Africans; pirates and roustabouts; all manner of people caught up in the violence of colonisation, the plantation economy, the Civil War, and so on.

What they all have in common is that something has been left undone, some need unmet, some plea unheard. They are still unsettled, and so they haunt. We call them 'haints'.

Unseen Histories

Did you have any early experiences with ghosts?

Noah Angell

Several. The one I describe in the book involves a man swinging an axe in an area of East Carolina that was once known for turpentine production, work that involved lots of swinging axes. Others are a bit harder to pin down, in terms of who they might have been.

Unseen Histories

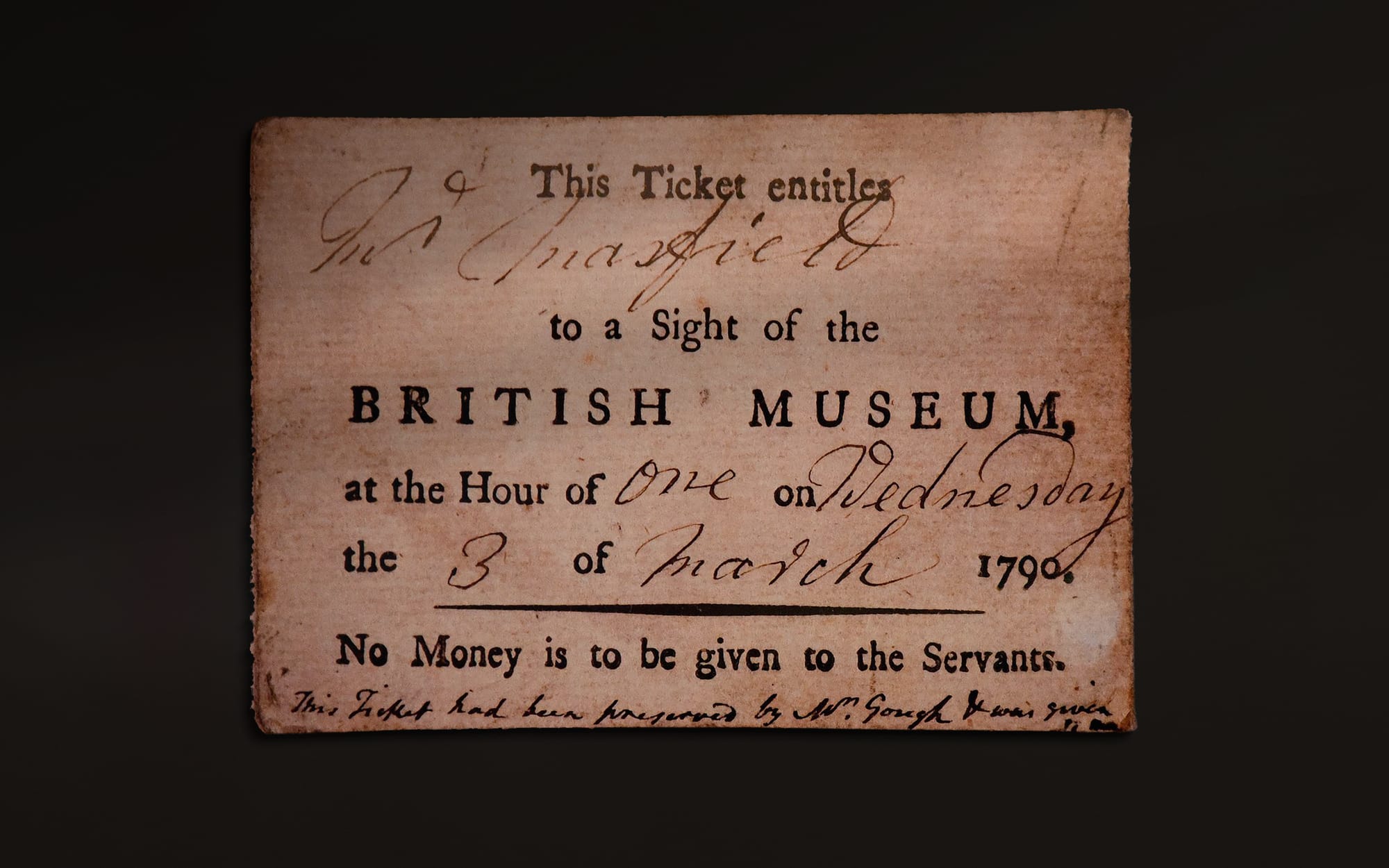

What was the genesis moment for Ghosts of the British Museum. Didn’t the idea arise out of an anecdote you heard in a pub?

Noah Angell

In the summer of 2015, I was in the pub with a curator with whom I was working at the time. Everyone gathered around the table was engrossed in storytelling, but the acoustics of the space were such that I couldn’t hear a thing.

After a while, I gave up straining my ears and reading lips, and I asked the curator what they were on about. She told me they all went to university together, and that during that time they worked at the British Museum, and they were telling ghost stories.

I wasn’t sure that I heard properly, so I asked her to confirm — the British Museum is haunted? She nodded with conviction. Soon after, I began to track people down who work at the museum, or who had done so in the past.

Unseen Histories

How willing were people – the museum staff, security and visitors – to share their stories with you?

Noah Angell

Of course, many people declined to speak to me, either because they had no knowledge or experience of the museum’s ghosts, or because they feared for their jobs.

Sometimes I sensed that people were afraid that speaking about the museum’s ghosts could deepen their engagement with them, and they didn’t want that.

Most chose to contribute stories anonymously. I was surprised by how many people were willing to talk.

I still don’t know what moved them to do so, but in the end, I spoke to dozens: overnight and daytime security staff, visitor services, collections managers, storage assistants, museum assistants, administrators, curators, maintenance workers, cloakroom and post room attendants and auxiliary workers of all kinds, surveyors, tour guides, independent researchers. All sorts.

Unseen Histories

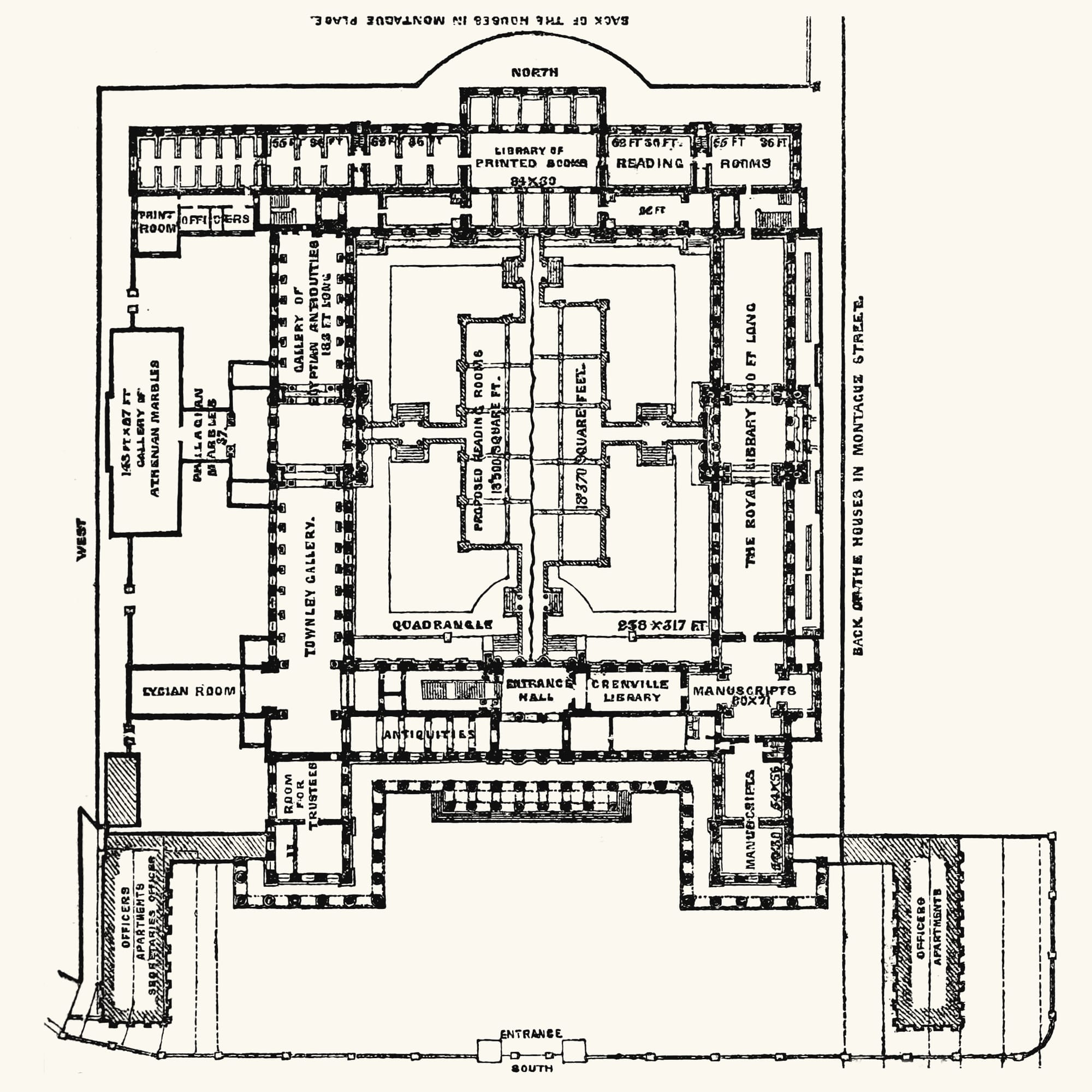

At the heart of your book is an extraordinary architectural space. You write of the British Museum’s 3,500 doors, endless rooms and corridors, and you mention something known as the ‘Stone Tape Theory’. Can you tell us about this?

Noah Angell

While researching the British Museum’s history, I sometimes came across the phrase 'British Museum Island', which I quite like. It is an island in the heart of Bloomsbury, in terms of the consolidation of real estate, but it is also an island of deep time. It’s full of fragments of much older temples and mausoleums.

The main Greek revivalist style building was designed by Robert Smirke in the nineteenth century, but there have been many piecemeal extensions, and for security reasons, an accurate map is not something the uninitiated can get a hold of. Most British Museum employees have never even been admitted to storage. So, it’s not a place that can be known in its entirety.

The 'Stone Tape Theory' was first coined in the late nineteenth century at Bloomsbury’s Centre for Psychical Research. Later it was popularised by the Christmas ghost story, The Stone Tape, which was produced by the BBC in 1972.

The Stone Tape Theory holds that not only objects, but buildings, in this case the British Museum’s own architectural skeleton, operate as something like recording devices, absorbing the energetic impressions of those inside them — people, material heritage and events that took place — including the deaths of museum staff and visitors.

From time to time, without warning, these recordings are aired for unsuspecting warders and visitors. Oddly enough, or perhaps not, several museum workers volunteered that they are believers in the Stone Tape Theory.

Unseen Histories

One of the best-known spaces in the Museum is the Great Court, which until 1997 was home to the British Library. Wasn’t this the site of a peculiar haunting?

Noah Angell

Yes. During the Germany: Memories of a Nation travelling exhibition there were extraordinary nightly disturbances which were picked up by CCTV feeds outside of Gallery 35, every night from half two to four in the morning.

Then, as the warders told me, 'When Germany went, they went.' This was the first instance I’d heard of a travelling exhibition bringing ghosts with it. Then everything settling down once the exhibition was deinstalled.

Unseen Histories

The biographer Richard Holmes once wrote that the ‘act of repeated touching, especially in the process of daily work or creation, imports a personal virtue to an inanimate object, gives it a fetishistic power in the anthropological sense, which is peculiarly impervious to the passage of time’. This is an idea you consider in Ghosts of the British Museum too, isn’t it?

Noah Angell

A visitor services staff member told me that 'When you play a violin, the violin retains your energy, and the energy of everyone who’s ever played that violin.' Many warders put it that 'objects hold energy.'

Some contend that each artefact is a vessel for memories in much the same way that we are. It is also true that many of the relics resident in the museum have been ritually imbued with powers — they are homes for ancestors and spirits, now exiled and kept apart from the people who know and care for them. That doesn’t just magically evaporate when the relics are given a catalogue number and put in a glass case.

The thing about the 'passage of time', is that when we speak of ghosts and spirits, it’s important to bear in mind that time operates differently on the other side. Everything which ever was, still is, and those things which have been left unresolved do not simply go away. On the contrary, if something needs to be resolved or revisited, it will call.

Unseen Histories

While working on the book you started to lead walking tours around the Museum. How did this shape your project?

Noah Angell

I began the walking tours before I knew that it was a book that I was working on, but they turned out to be formative research for the book.

I began them as a way of practising the telling of these stories. The groups would be quite mixed, so you’d have Australian schoolteachers on short term contracts who just love Harry Potter. You’d have the Soho occultists, researchers of the post-colonial from over at SOAS [School of African and Oriental Studies], Birkbeck and UCL [University College London], museum workers from all over, and just plain old punters, and I had to find a way to tell the stories so that it hit the right notes for each of them.

I’d often go to the pub with them after the tour and get their read on the material, which was valuable. In the end, the sequence of chapters follows the arc of the walking tour — from 'Clocks and Watches', snaking through the galleries ‘til we end up at the Upper Egyptian Gallery. But then all roads lead to storage. The museum is mostly storage, and the public isn’t allowed there.

Unseen Histories

Of all the rooms in the Museum, it is the Upper Egyptian Gallery that seems to have the most powerful effect upon you. Is that correct?

Noah Angell

I wouldn’t say that. It has a bunch of dead people in it, and we human beings have a powerful, pre-cultural aversion to being in the presence of an exposed corpse.

Those present in the Upper Egyptian gallery are a small fraction of the more than six thousand sets of human remains held in storage, most of them in the basement 'morgue'.

The Upper Egyptian Gallery makes me feel physically ill — in the pit of my stomach, but I wouldn’t say it has the most powerful effect on me. I listen to what the warders tell me. The Sutton Hoo, the Enlightenment Gallery, the Upper Egyptian Gallery are said by staff to be among the most haunted public-facing spaces, each for different reasons.

But given what I know, it’s hard for me to see the museum this way. I experience the museum as something like a black hole, and within that black hole, it’s all intermingling and happening at once. The galleries are numbered, but they bleed into each other. It’s all tangled up like a snake pit 𖡹

Born in the US, he was resident in London for over a decade and now lives in Berlin. Ghosts of the British Museum is his first book.

Ghosts of the British Museum: A True Story of Colonial Loot and Restless Objects

Monoray / Octopus Publishing Group, 11 April, 2024

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-1800961340

"Fascinating and illuminating"

– Peter Ackroyd

What if the British Museum isn't a carefully ordered cross section of history but is in instead a palatial trophy cabinet of colonial loot - swarming with volatile and errant spirits?

When artist and writer Noah Angell first heard murmurs of ghostly sightings at the British Museum he had to find out more. What started as a trickle soon became a deluge as staff old and new - from overnight security to respected curators - brought him testimonies of their supernatural encounters.

It became clear that the source of the disturbances was related to the Museum's contents - unquiet objects, holy plunder, and restless human remains protesting their enforced stay within the colonial collection's cabinets and deep underground vaults. According to those who have worked there, the institution is heaving with profound spectral disorder.

Ghosts of the British Museum fuses storytelling, folklore and history, digs deep into our imperial past and unmasks the world's oldest national museum as a site of ongoing conflict, where restless objects are held against their will.

It now appears that the objects are fighting back.

"A heady cocktail of history and folklore that leaves a haunting aftertaste... Spine-tingling"

– Lindsey Fitzharris

"An absorbingly creepy travelogue through the corridors, tunnels and basements of our most famous cultural repository. With Noah Angell as our guide, the British Museum becomes a haunted prison filled with imperial plunder and restless spirits clamouring for attention"

– Malcolm Gaskill

With thanks to Monoray