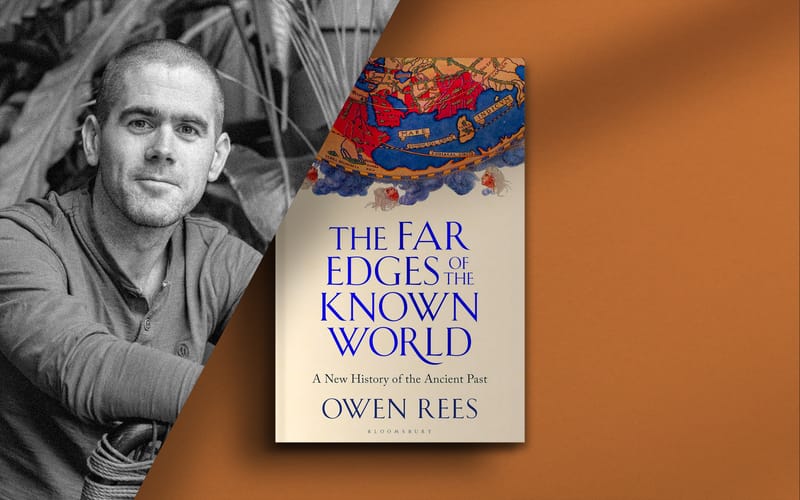

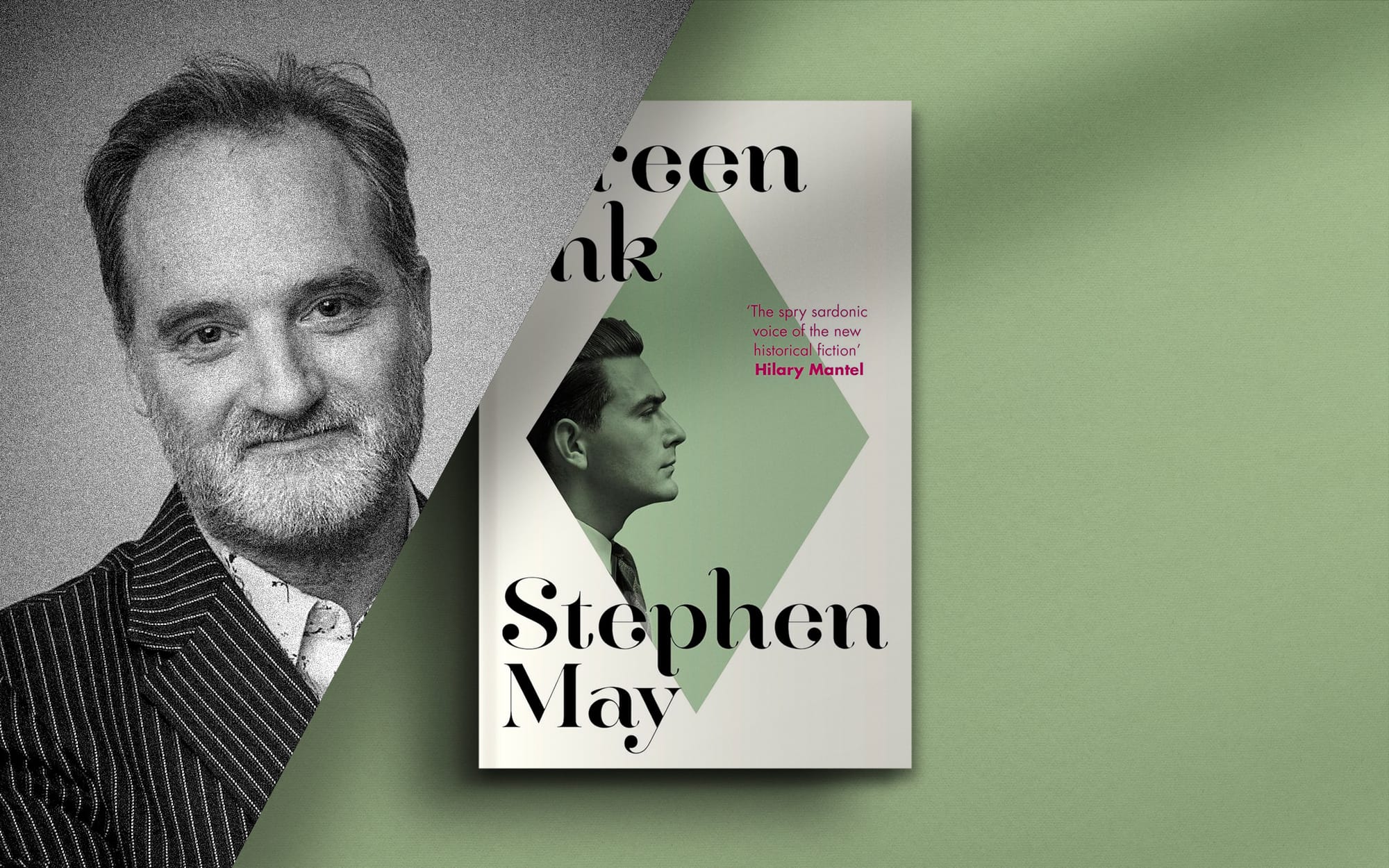

Green Ink with Stephen May

In his compelling new novel Stephen May engages with one of the great mysteries in British political history

No one really knows what happened to Victor Grayson, the fiery socialist politician who disappeared, in September 1920. For more than a century different theories have been advanced but none have been proven.

The only certainty is that several groups of people - including the Prime Minister David Lloyd George - wished Grayson gone.

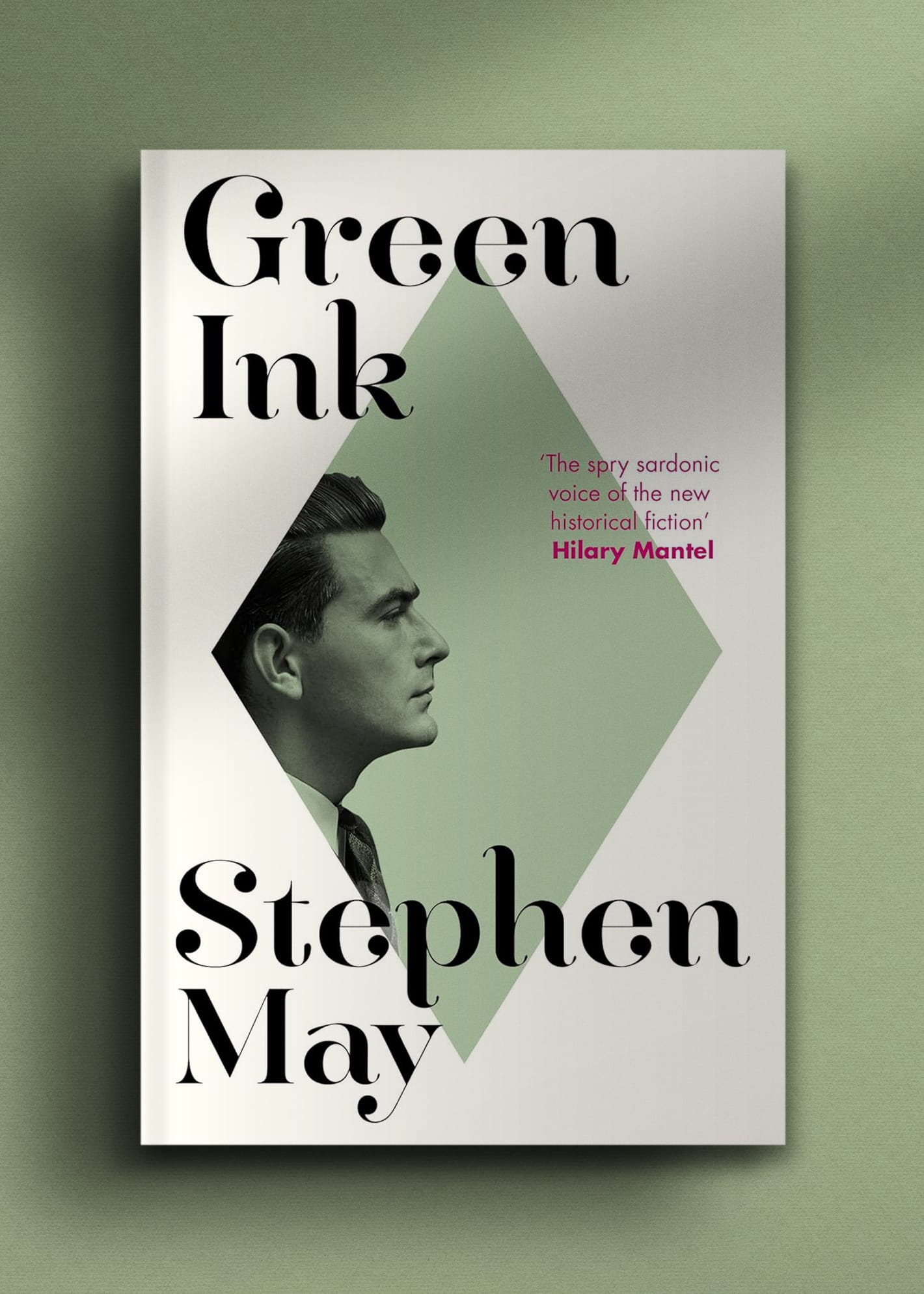

It is Grayson's story that the author Stephen May has rekindled in his new book, Green Ink.

In this excerpt we feature the prologue to May's novel and then we put some questions to him about the vibrant character at the heart of his story and the confused times in which he lived.

Prologue

The man lies sprawled on his back in the soaked muck of Palmerston Street. He coughs and he chokes. By his side his fingers flex. Curl and uncurl. Grip and release, trying to get some kind of purchase on the putrid city air.

A woman approaches him with a confident long-legged stride, athletic in her army breeches. She looks with fascination at the neat hole in his waistcoat. Her ears are ringing, a sudden and hellish tinnitus, a headful of breaking glass. She unbuttons the man’s waistcoat and the shirt beneath it. The man trembles. Shivers… Seems to gather some strength from the bruised and frowning night, to borrow some energy from the density of it. Now he is writhing on the rutted and potholed ground, legs kicking in feeble agitation. He’s a desperate beetle on its back. He whispers obscenities, gouges out a sob. She feels an intense relief. He’s alive!

The man has been shot in the stomach, but looking at him now, all the woman can see is a prettily pink-frilled contusion on the surface of his belly. It looks almost innocuous. Almost artistic, in fact. Back in the war, an injury like this would have been taped up and he’d have been sent back into the crazed, star-shelled glow of no man’s land within half an hour.

What she doesn’t yet know is that the bullet has lodged near his spine. And that on the way there, it seared its way through his intestines, his pancreas, his spleen, shredded his diaphragm and drilled through his lungs. Tissue in every one of these organs is exenterated. Diced. The pressure wave caused by a bullet travelling at 850 feet per second has ripped flesh from his ribcage. Tendons have turned to pulp. Treacle-thick, treacle-black arterial blood is seeping into the cavity of his chest.

The woman may not know yet that there can be no good outcome, but the man does. As he lifts his head from amid the filth of Palmerston Street, the horse shit, the spilled vegetables, the slopped remains of hurried dinners, the congealing guck and the slimy rubbish, the man knows that you don’t come back from this kind of wound.

No actual pain yet, but this man, this veteran of the Western Front, this former hero, knows that this too is not a good sign. When wounded, what you want is for Pain to arrive quickly, before the nurses, before the doctors, before the fussing with bandages, stretchers and ambulances. Pain first, first aid later, that’s the rule of survival. Where Pain takes its time, where it dillies and dallies, it allows nastier things to get in. Shock, sepsis, gangrene and all the other microscopic jackals of fatal debilitation, if they can nip in ahead of Pain to begin their silent work, then you are taking the count. Everyone who has ever been in the forces knows this.

So, this is it, he thinks. This is how it ends. Doesn’t seem right. Doesn’t seem fair. Just as things were looking up.

He mutters something. The woman moves closer to him, that clanging in her head, it’s still making her dizzy, making her slow.

What?’ she says. ‘What did you say?’

‘Bollocks. I said bollocks. Now just bloody well help me will you? Do summat!’

The flat and bolshy Northern vowels push hard against the folded arms of the London night, but there’s no real power there. The man’s voice collapses into a damp gurgle. No surprise that in this extremity his roots are showing. This happens to everyone. Like the poet almost says, in the end we show our beginning. Reveal ourselves for what we are, for what we have always been.

This is an extract from Green Ink by Stephen May, which is published by Swift Press on 13 March, 2025.

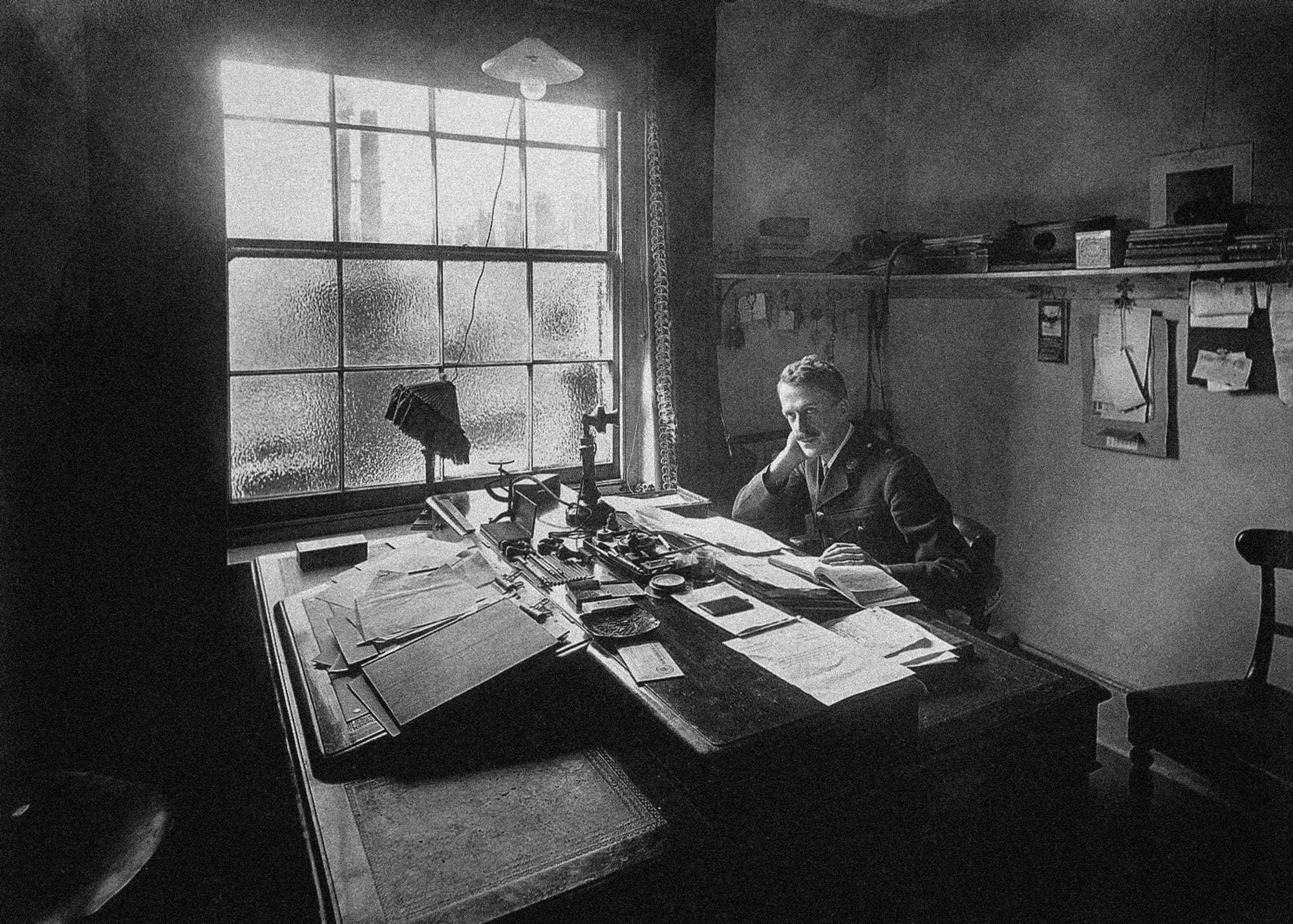

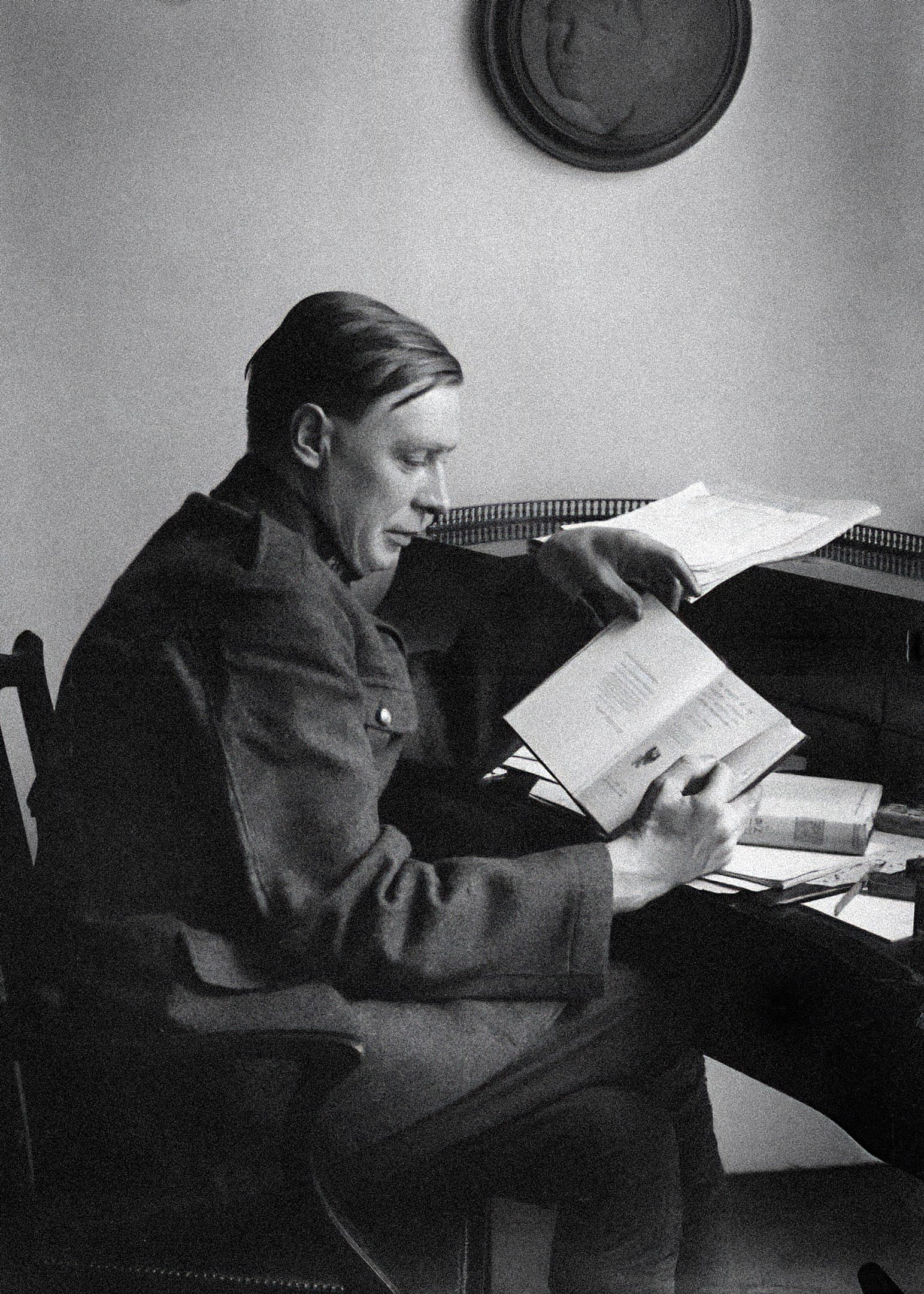

Victor Grayson

Albert Grayson (known as Victor) was born in Liverpool in September 1881. As a young man he displayed a talent for public speaking and by his early twenties he was addressing large socialist gatherings to an enthusiastic response.

From 1906 onwards his political career rose on a steep trajectory. The following year he astonished the political establishment by narrowly winning the Parliamentary seat for Colne Valley without the firm backing of the Labour Party. For some years afterwards he remained a popular, tumultuous figure on the national political scene.

As well as a ‘spellbinding’ orator, Grayson was known as a fearless journalist. When war came in 1914 he was strongly supportive of Britain’s active participation in it. After these years of conflict, though, Grayson was rumoured to be living in poverty.

Then, in September 1920, he vanished. All subsequent sightings of him proved to be inconclusive and no death certificate has ever been issued. The question of what happened to this political maverick was left to linger as one of the great mysteries in Leftist political history.

Stephen May on Victor Grayson, War, Trauma and Politics

Unseen Histories

Victor Grayson’s life is a mix of the heroic, tragic and mysterious. When did you first became aware of his strange story?

Stephen May

I can’t really remember now when I first became aware of Grayson. He was MP for a constituency near where I live ( I live in the Calder valley and the Colne Valley is the next major valley along from ours, just ten miles away or so and with the same mix of small mill towns and villages).

I think I’d dimly heard his name and came across him again when researching the political scene of 1907 for my last novel Sell Us The Rope which takes place at a Communist Party conference of that year. 1907 was a big year for the far-left!

Unseen Histories

You depict a society traumatised by a terrifying war. Was capturing this sense of psychological damage one of your major aims in Green Ink?

Stephen May

Yes. I was writing it in the immediate post-covid world and the sense of emotional exhaustion and political anger that characterised our discourse then felt similar to how things must have been in the years following the Great War and the lethal flu epidemic that came after that.

Unseen Histories

Politics is especially charged at the moment, as it was in 1920, a strong mix of utopianism and the sordid. Is this right?

Stephen May

I think so. Social media has driven a lot of it of course. Mad conspiracy theorists can find an audience much more easily than they could in the pre-Internet era. People have access to all sorts of strange ideas at the click of a link. And of course the world is also saturated in freely available pornographic imagery.

The post-war shake up of the 1920s was similar in the sense that the old world was dead, but that a new world was struggling to be born (I’m paraphrasing Gramsci here) and in the ruins of the old order, new ideas – both good and bad – found some space.

Spiritualism was massive just after the war, so was evangelism, so were various other isms – Feminism, Socialism, Communism, Fascism, Nationalism. People were searching for new answers to the old problems. Just like now. And often getting it wrong. Just like now.

Unseen Histories

David Lloyd George is the dominating historical figure in the story. Was he an enjoyable character to write?

Stephen May

I think of him as a kind of Boris Johnson figure. A rogue. A rascal. Probably fun to have a pint with. Smart though, and a survivor.

He was part of the Liberal government of 1906 and he was still in the War Cabinet in 1940. Yes, he was fun to spend time with and also, considering the impact he had on his time, he seems oddly forgotten.

Unseen Histories

Green Ink has a seam of dark comedy running through it. Was this humour a feature of the time?

Stephen May

If you read Vera Brittain’s great book Testament of Youth about her time as a nurse in the First World War, you get a sense of how gallows humour helped people cope with the trauma of the time. And certainly just after the war, music hall, theatre, film, spectator sport all saw big increases in attendances and there were new social attitudes too.

The kind of sexual license that previously only the upper classes had got away with began to spread into the bohemian middle class. There was a new playfulness everywhere.

Unseen Histories

Imperial London provides you with a vivid setting. Often the story plays out on streets that no longer exist in neighbourhoods that have completely changed. How did you research the detail and do you think it is important to get it right?

Stephen May

The Luftwaffe redesigned a lot of London’s streets. And the town planners finished what they started. I tried to get most things right, but let’s just say, I didn’t let London’s geography get in the way of the narrative thrust of my book.

Unseen Histories

What is your estimation as Victor Grayson as a figure in left wing history?

Stephen May

To have escaped poverty the way that he did, to become the most recognisable figure on the Left at the age of 25. To fly in the face of the morality of the time, it’s impressive stuff. As a human being he is fascinating and his story is compelling. As a leader he was almost totally ineffective, and ultimately as self-serving as any other politician. No hero that’s for sure 𖡹

He has also been shortlisted for the Wales Book of the Year and is a winner of the Media Wales Reader’s Prize. He has also written plays, as well as for television and film. He lives in West Yorkshire.

Green Ink

Swift Press, 13 March, 2025

RRP: £16.99 | ISBN: 978-1800754676

"The spry, sardonic voice of the new historical fiction"

– Hilary Mantel

David Lloyd George is at Chequers for the weekend with his mistress Frances Stevenson, fretting about the fact that his involvement in selling public honours is about to be revealed by one Victor Grayson.

Victor is a bisexual hedonist and former firebrand socialist MP turned secret-service informant. Intent on rebuilding his profile as the leader of the revolutionary Left, he doesn’t know exactly how much of a hornet’s nest he’s stirred up. Doesn’t know that this is, in fact, his last day.

No one really knows what happened to Victor Grayson – he vanished one night in late September 1920, having threatened to reveal all he knew about the prime minister’s involvement in selling honours. Was he murdered by the British government? By enemies in the socialist movement (who he had betrayed in the war)? Did he fall in the Thames drunk? Did he vanish to save his own life, and become an antiques dealer in Kent?

Whatever the truth, Green Ink imagines what might have been with brio, humour and humanity; and is a reminder that the past was once as alive as we are today.

"Vivid and wholly credible recreation of post-Great War London"

– Robert Edric

"Intrigue, betrayal, redemption"

– Rachel Seiffert

With thanks to Tabitha Pelly. This excerpt is republished with permission from Swift Press