Herbert Ponting's Photographs of Antarctica in Colour

Colourised and remastered images from Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova Expedition

On 29 March 1912, Captain Robert Falcon Scott died in the Antarctic. The story of his tragic race to the South Pole in 1912 – when Scott was narrowly beaten by the Norwegian adventurer Roald Amundsen and then died on his return journey – is one of the best known from the heroic age of Antarctic exploration.

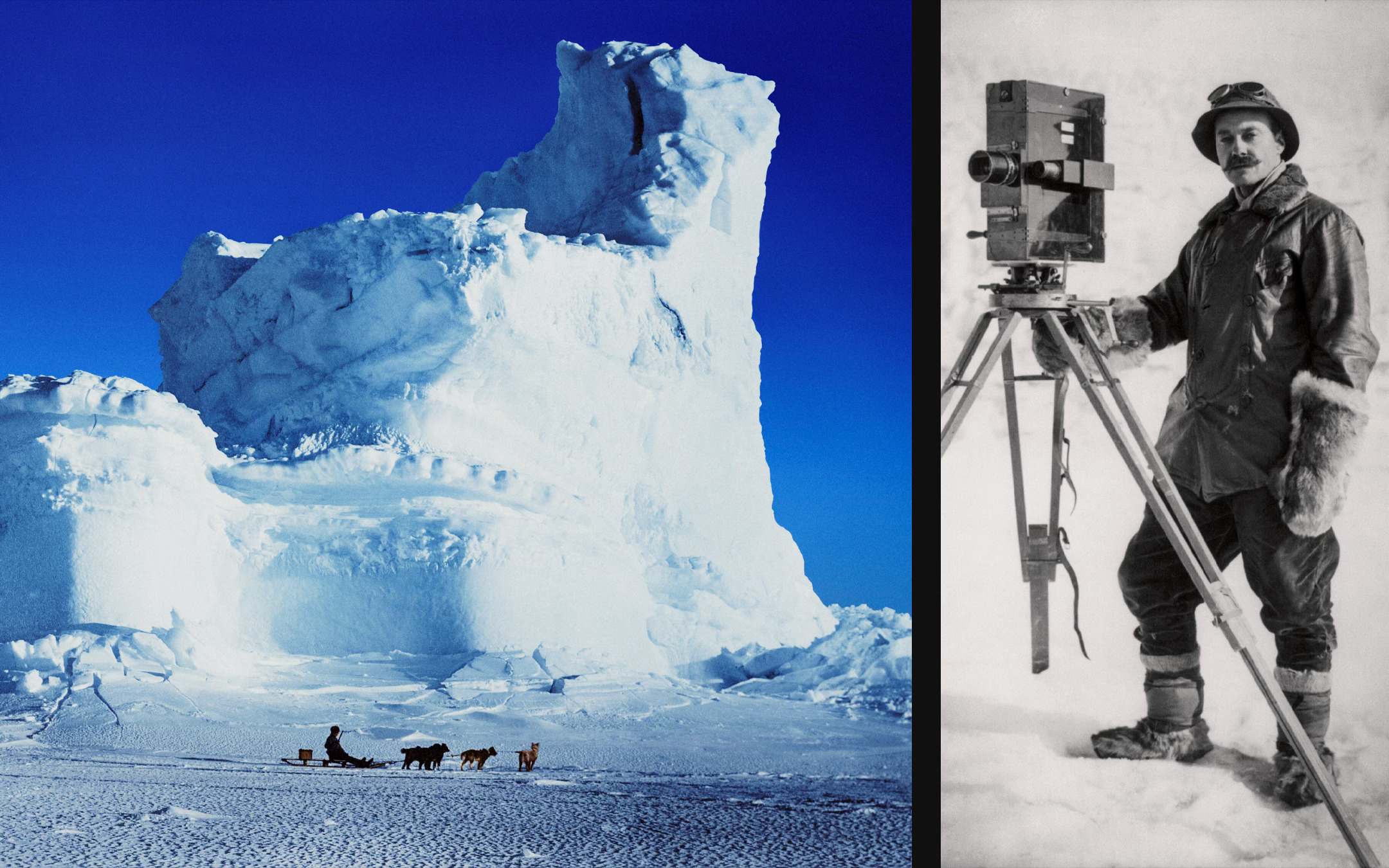

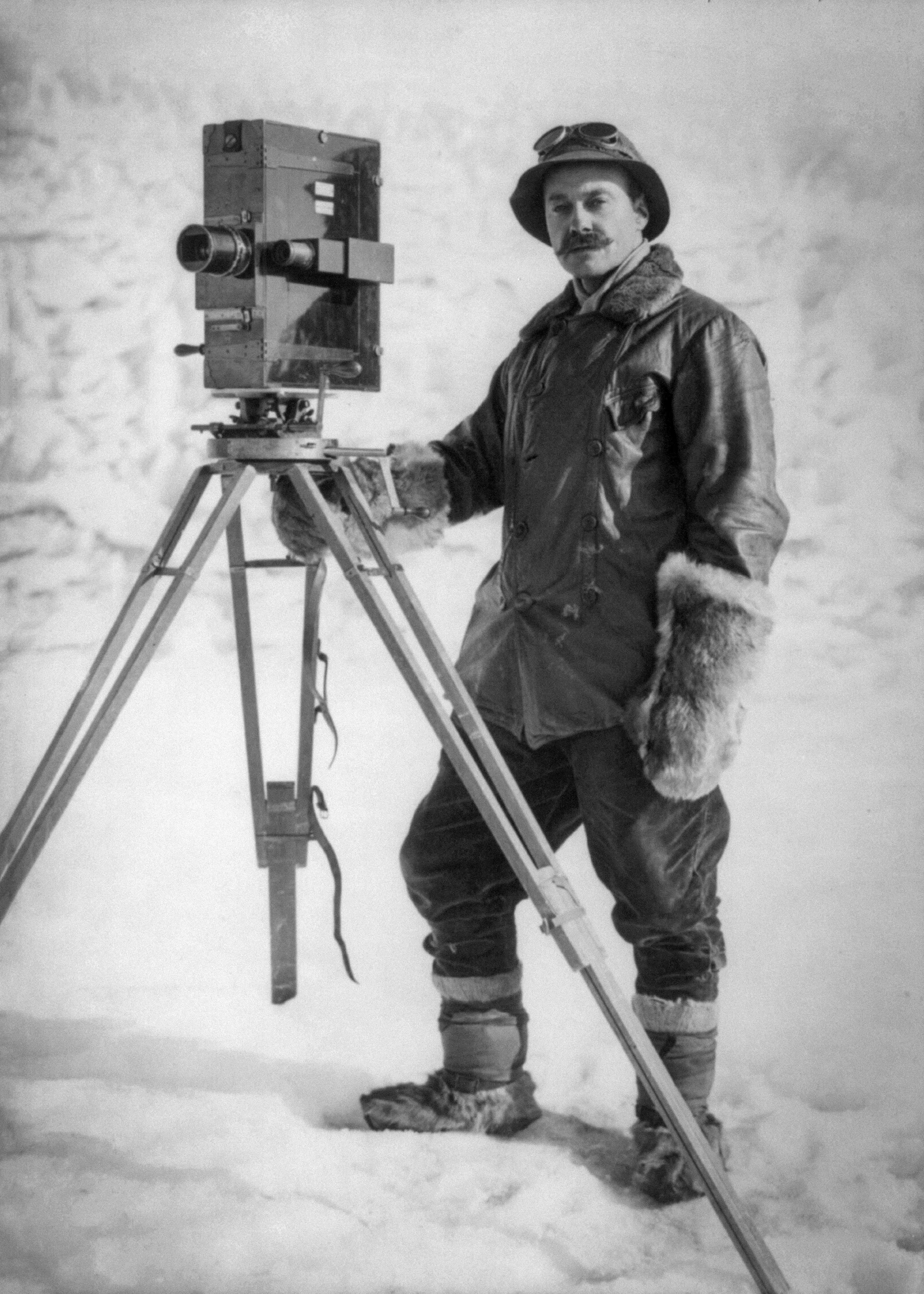

Another celebrated aspect of Scott's '‘Terra Nova Expedition’ is the documentary work that was undertaken by the photographer Herbert Ponting. Ponting's images of an ice-bound world enchanted the British public when they were published a century ago.

In this Viewfinder feature, we reflect on this superb body of work and try to realise an ambition that Ponting himself could not achieve – to present the Antarctic world in ‘natural colours’.

Words by Peter Moore

With curated and remastered images from the public archives by Jordan Acosta

Among the arsenal of photographic equipment that Herbert Ponting carried with him, as the Terra Nova sailed from New Zealand, bound for Antarctica, on 29 November 1910, were several intriguing boxes that had been presented to him by the ‘'Messrs Lumière & Co. of Lyons’.

These boxes contained a number of ‘Autochrome’ plates, which would enable Ponting to test a new colour process that Auguste and Louis Lumière had developed over the past decade. To experiment with this technology in such an unknown, sublime landscape was an alluring prospect. By 1910 Ponting was widely regarded as one of the world’s leading out-door photographers. But capturing ‘natural colours’, for him as much as anyone else, had long remained an impossible dream.

The first Autochrome plates had gone on public sale at the Lumière factory in Lyon in 1907. These were made of the usual glass, but they were sprinkled with little transparent starch grains, dyed red, blue and green, that would act as colour filters in an exposure. It was a complicated process that required multiple exposures and developments. Ponting, however, while unsure of the plates’ ability to withstand the temperature fluctuations and endless buffeting of months at sea, was keen to give it a go.

Having reached Antarctica in the new year of 1911, Ponting duly attempted some Autochrome exposures. As he suspected, the plates had degraded during the voyage, but as the autumn light spread over the Terra Nova base at Camp Evans in April he did succeed in capturing some ‘beautiful afterglow effects’ of the sun.

Ponting’s experiments with Autochrome are interesting to view today. They leave us, too, with an intriguing question. His series of pictures, taken during Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-starred 1910-13 expedition to the South Pole, are widely regarded as being among the finest in the history of photography. But what would these images have looked like, as Ponting put it himself, ‘in natural colours’?

Here we provide our answer to that question. Over the last few weeks, as we approach the anniversary of Robert Falcon Scott’s death on 29 March, Jordan Acosta has been producing a series of new, restored and colourised images, which are drawn from Ponting’s original photographs in the public domain that are held in the archives of the Library of Congress.

Herbert Ponting was born in Salisbury, Wiltshire. His father was a banker and while Herbert was still young the family moved north where he took a job in Preston, Lancashire. It was there that the elder Ponting made his fortune. Herbert, however, was not drawn to the steady rote of business. He grew up in the first age of popular photography. It was said that his great joy was to escape the town and visit the Lake District with his camera.

In early adulthood Ponting migrated to California where he worked for a time as a fruit farmer. Photography, though, was always his driving passion. Friends noticed that he had a natural flair for composition and this was acknowledged when he had a photograph accepted at the San Francisco Salon. Buoyed by this, in 1901 he left his wife and young children and embarked on a photographic tour of Japan. Over the decade that followed Ponting established his reputation. At a time of high empire, he displayed an intrepid streak of character. His photographs of the distant East were exhibited in the galleries of London.

It was in the autumn of 1909 that Ponting crossed paths with the polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott. At that point Ponting had been planning a multi-year tour of the British Empire for a publication by the Northcliffe Press, but there was something about Scott that intrigued him. He later wrote:

‘I was drawn strongly to the famous explorer at my first meeting with him. His trim athletic figure; the determined face; the clear blue eyes, with their sincere searching gaze; the simple, direct speech, and earnest manner; the quiet force of the man—all drew me to him irresistibly. During this, our first interview, he talked with such fervour of his forthcoming journey; of the lure of the southernmost seas; of the mystery of the Great Ice Barrier; of the grandeur of Erebus and the Western Mountains, and of the marvels of the animal life around the Pole, that I warmed to his enthusiasm.’

– Ponting on his first meeting with Scott

And so, at the end of November 1910, on a salary of £5 per week, Ponting carried his various cameras (Ponting's J.A. Prestwich camera is shown in the above portrait) and all of his boxes of photographic equipment aboard the Terra Nova.

‘This stupendous work of Nature’

The seas to the south of New Zealand are infamously raw and tempestuous. Anyone travelling to the south has first to pass through the ‘Furious Forties’ before they progress into the even more testing environment of the ‘Shrieking Sixties’. Although Ponting was a seasoned traveller, he suffered terribly from seasickness during the early part of December. Scott watched him wryly. ‘Yesterday he was developing plates’, Scott wrote, ‘with the developing dish in one hand and an ordinary basin in the other.’

By 10 December, when the Terra Nova crossed the Antarctic Circle, the storms were beginning to give way to a entirely different seascape that was characterised by ice. Soon Ponting was gazing out at his very first iceberg, something he beheld with wonder.

‘In all my travels in more than thirty lands I had seen nothing so simply magnificent as this stupendous work of Nature. The grandest and most beautiful monuments raised by human hands had not inspired me with such a feeling of awe as I experienced on meeting with this first Antarctic iceberg.’

The colourised photograph above shows the Terra Nova as it battled through heavy pack ice on 13 December. It is interesting to note that Ponting is already being dynamic with his compositions. He has left the safety of the ship and clambered onto the ice in search of a novel viewpoint. Just a fortnight after they sailed, the colourisation emphasises the excellent condition of their ship with its gleaming strakes and handsome sails. The bowsprit rises gently over a peculiar knoll of ice while the figures aboard look watchfully out.

Another feature of the Terra Nova's decks during the southerly drive to the south were the huskie dogs that can be seen in this remastered photograph (above).

Thirty-three Siberian huskies formed a part of the expedition at the outset and, at this point, they were very much a divisive issue. Scott was unsure about their usefulness in Antarctica as they had performed indifferently on a previous expedition. But Roald Amundsen, Scott’s great Norwegian rival who was beginning his own expedition towards the South Pole (he would eventually beat the British by little more than a month), was known to be using them.

Scott’s misuse of the dogs would become a contentious issue in later accounts of the Terra Nova Expedition. Some have pointed out that the British had little tradition of using such animals in comparison with other nations. This lack of understanding – of knowing what to feed them and how to treat them – hampered their effectiveness.

Scott, too, like many Britons had an inflated sense of empathy with the creatures that Ponting depicts here, berthed on the open deck. Scott fretted that the animals were dreadfully exposed to the weather and that they whined constantly as a result. They were endlessly drenched by icy waves. Once, a dog named Osman, who would become ‘Scott’s best sledge dog’, was washed overboard, before being swept back on again.

Ponting had special reason to be interested in the dogs, which were the responsibility of his friend Cecil Meares. Funds for the purchase of the animals had been raised by schools across Britain, who were eager to contribute to the patriotic enterprise. Having raised specific sums, the various schools were given the privilege of naming their own allocated dog. As well as 'Osman' there was a 'Cook', a 'Vaida' and a 'Biela Noogis', although the dogs cheerfully ignored these names in favour of their old Russian ones.

Into Antarctica

‘Bright sunny weather, an ice-free sea and a fair wind were all that we could desire, and we bowled merrily along with all our canvas pulling and bellying to the breeze. Great swelling billows of cumulus – glorious contrasts of light and shadow – floated in the heavens, or detached themselves into woolly clusters.

Such weather made the very drawing of the breath of life a joy. It filled one with a sensation of delight to throw back the arms, expand the chest and, opening wide the lungs, inhale great stimulating draughts of the sweet exhilarating air. It made one thrill and tingle with very gladness to be alive, and to have health and strength and feel the marvel of it all.’

– Herbert Ponting, New Year 1911

The joy of encountering a new landscape for the first time is something that many have experienced. In Ponting’s case, this sensation was hugely amplified and it generated a series of spectacular results. Having rounded the tip of Ross Island and worked into McMurdo Sound, the Terra Nova came to anchor on 4 January 1911. Around him was a world unlike anything Ponting had ever seen before.

Over the days and weeks that followed, Ponting took some of his best-known photographs. One of these (directly above) shows the ship, lying to, ‘serene and silent’ in the Antarctic water. As well as the outline of the Terra Nova in the distance, Ponting seems interested in the reflections of the ice close by. Little icicles hang down from the irregular heaps that have piled up near his feet. Far away, the polar sky is scratched with cirrus clouds.

By the time Ponting captured this image of the Terra Nova, he had made another exciting discovery. Venturing about a mile away from the ship he found an iceberg with a hollowed out middle. It was, in his estimation, ‘the most wonderful place imaginable’. The view was curiously contrasting. From outside ‘the interior appeared quite white and colourless, but, once inside, it was a lovely symphony of blue and green’.

Interior / Exterior of the Grotto iceberg. Ponting’s first week in Antarctica was filled with surprise and excitement. The discovery that filled him with most delight was that of a ‘most wonderful grotto’, just a mile away from the ship. Having persuaded his shipmates to visit the site, he photographed the grotto inside and out. (⇲ Library of Congress) Photograph Herbert George Ponting. 5 January 1911, Antarctica. This photograph has been restored and colorized from an original black and white digital scan by the Unseen Histories Studio

‘I made many photographs in this remarkable place – than which I secured none more beautiful the entire time I was in the South. By almost incredible good luck the entrance to the cavern framed a fine view of the Terra Nova lying at the icefoot, a mile away.’

Ponting was so taken by his discovery that he enticed some other members of the expedition to join him there. Here in this colourised image above) you can see two of the ship’s company, Griffith Taylor and C.S. Wright, examining an enchanting scene that David Hempleman-Adams has since called ‘one of the iconic photographs of Antarctica’.

Other photographs from these weeks capture the awesome ramparts of Mount Erebus, the eerie shine of the midnight sun, and the beguiling forms created by the frozen environment. The ice came in several distinct variations. There were the wind-scoured ridges that rose fiercely upwards. In contrast was the young, ‘greasy’ ice that lapped at the water’s edge, and the rounded cakes of pancake ice that floated in the shallows.

For a photographer of Ponting’s ability, who worked so well with light and shape, this was an ideal and seductive environment. Commenting on the quality of his work, the Irish painter John Lavery, a member of the Royal Academy, would later state, ‘If I were to have painted any of these scenes, I would not have altered either the composition or the lighting of any of them in any way whatsoever’.

One other subject enchanted Ponting almost as much as the ice grotto. This was a colossal iceberg that towered high over all the others (below). He returned to view the iceberg over and again, giving it the name ‘Castle Berg’ for its stately form. He wrote that when it was bathed in the intense polar sunlight:

‘... the berg became of such gleaming beauty that even the most unimpressionable members of our community felt the influence of its spell. There was but one opinion concerning it amongst us – that it was the most wonderful iceberg ever reported in the Polar regions.’

Throughout this time Ponting was pioneering the persona of a travel photographer. This was still something of a novel role and several members of the Terra Nova Expedition found Ponting to be a challenging character. Many of them resented the fact that he was excused from the general toil and that he existed somewhat apart from the rest of them.

As time passed, though, Ponting earned respect for his total commitment to his trade. From the first days of the voyage they had seen him going to tremendous, and sometimes perilous, lengths to secure a shot. On the Terra Nova he had once mounted the shrouds in a Force Ten gale in order to capture the view along the gunwales, as the ship rolled heavily to starboard.

ColorGraph™ presents the most incredible colorized photography bringing the past to life. From start to finish, a ColorGraph print is made with exceptional care and attention. To mark its provenance, we emboss each one in the final stage of the hand-finishing process.

Ponting’s aloofness also became the source of humour. Some branded him a ‘Jonah’ because he had an unfortunate habit of involving himself in dangerous scrapes. The geologist, Griffith Taylor, meanwhile invented a neologism ‘to pont’ that described the act of being required to pose uncomfortably for Ponting’s camera. Some doggerel followed in due course:

I’ll sing a little song, about one among our throng,

Whose skill in making pictures is not wanting.

He takes pictures while you wait, ‘prices strictly moderate’;

I refer, of course to our Professor Ponting

Then pont Ponko, pont and long may Ponko pont;

With his finger on the trigger of his gadget.

For whenever he’s around, we’re sure to hear the sound

Of his high-speed cinematographic ratchet.

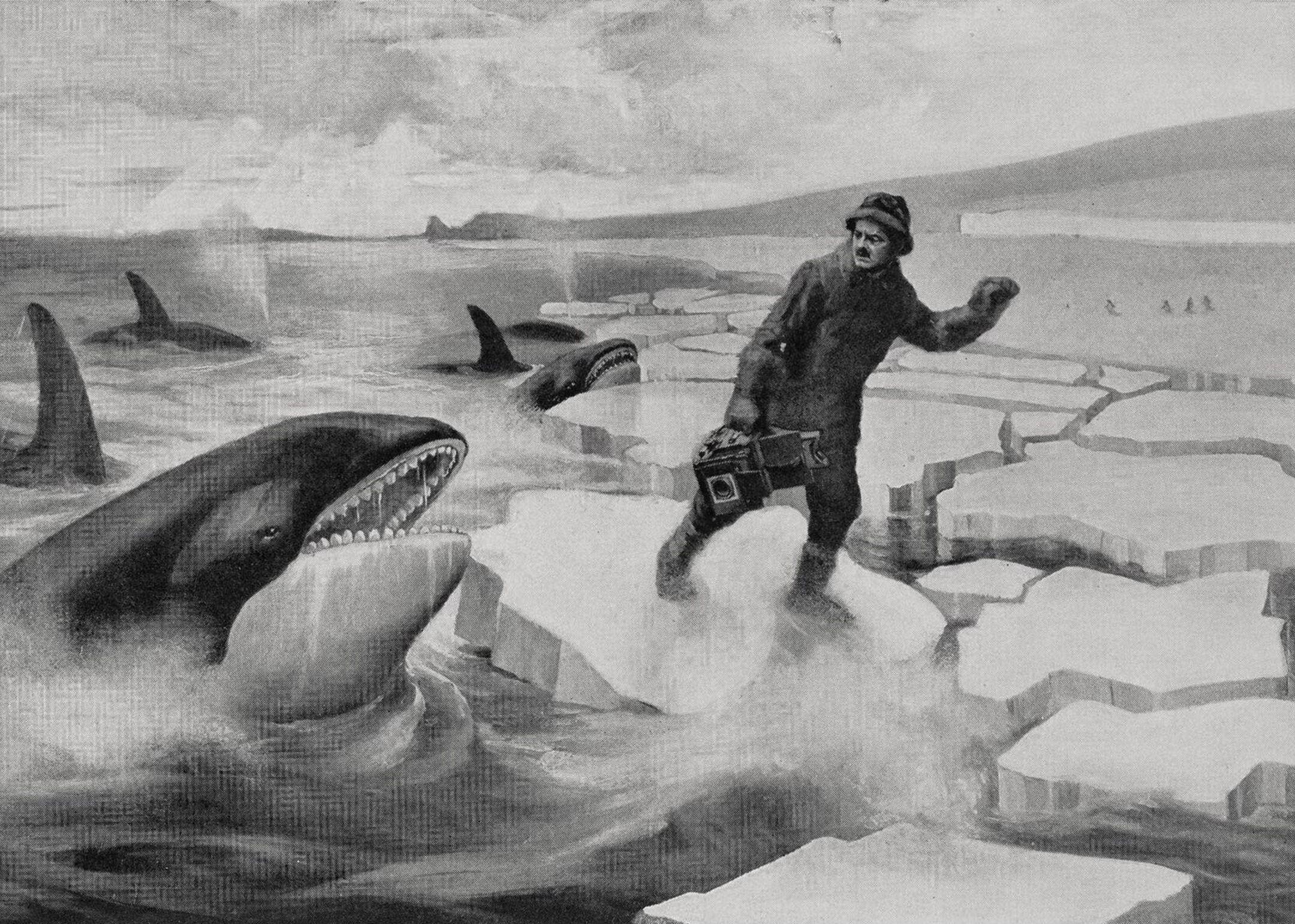

Ponting’s supreme moment of danger came in those early January days, when he was exploring the ice grotto and gazing up at Mount Erebus. Then, while heaving a sledge loaded with camera equipment across the ice, he spotted eight killer whales in the water nearby. Desperate to capture them, he hurried to the place where he estimated they would emerge from their next dive.

I had got to within six feet of the edge of the ice—which was about a yard thick —when, to my consternation, it suddenly heaved up under my feet and split into fragments around me; whilst the eight whales, lined up side by side and almost touching each other, burst from under the ice and 'spouted'.

The head of one was within two yards of me. I saw its nostrils open, and at such close quarters the release of its pent-up breath was like a blast from an air compressor.

The noise of the eight simultaneous blows sounded terrific, and I was enveloped in the warm vapour of the nearest 'spout', which had a strong fishy smell. Fortunately, the shock sent me backwards, instead of precipitating me into the sea, or my Antarctic experiences would have ended somewhat prematurely.

Ponting dashed away to the shouts of ‘Look out!’, ‘Run!’

But I could not run; it was all I could do to keep my feet as I leapt from piece to piece of the rocking ice, with the whales a few yards behind me, snorting and blowing among the ice blocks.

I wondered whether I should be able to reach safety before the whales reached me; and I recollect distinctly thinking, if they did get me, how very unpleasant the first bite would feel, but that it would not matter much about the second.

Captain Scott, who witnessed the whole episode, documented this harrowing affair from a different point of view:

One after another their huge hideous heads shot vertically into the air through the cracks which they had made. As they reared them to a height of 6 or 8 feet it was possible to see their tawny head markings, their small glistening eyes, and their terrible array of teeth-by far the largest and most terrifying in the world. There cannot be a doubt that they looked up to see what had happened to Ponting and the dogs. The latter were horribly frightened and strained to their chains, whining; the head of one killer must certainly have been within 5 feet of one of the dogs.

After this, whether they thought the game insignificant, or whether they missed Ponting is uncertain; but the terrifying creatures passed on to other hunting grounds ...

Scott of the Antarctic

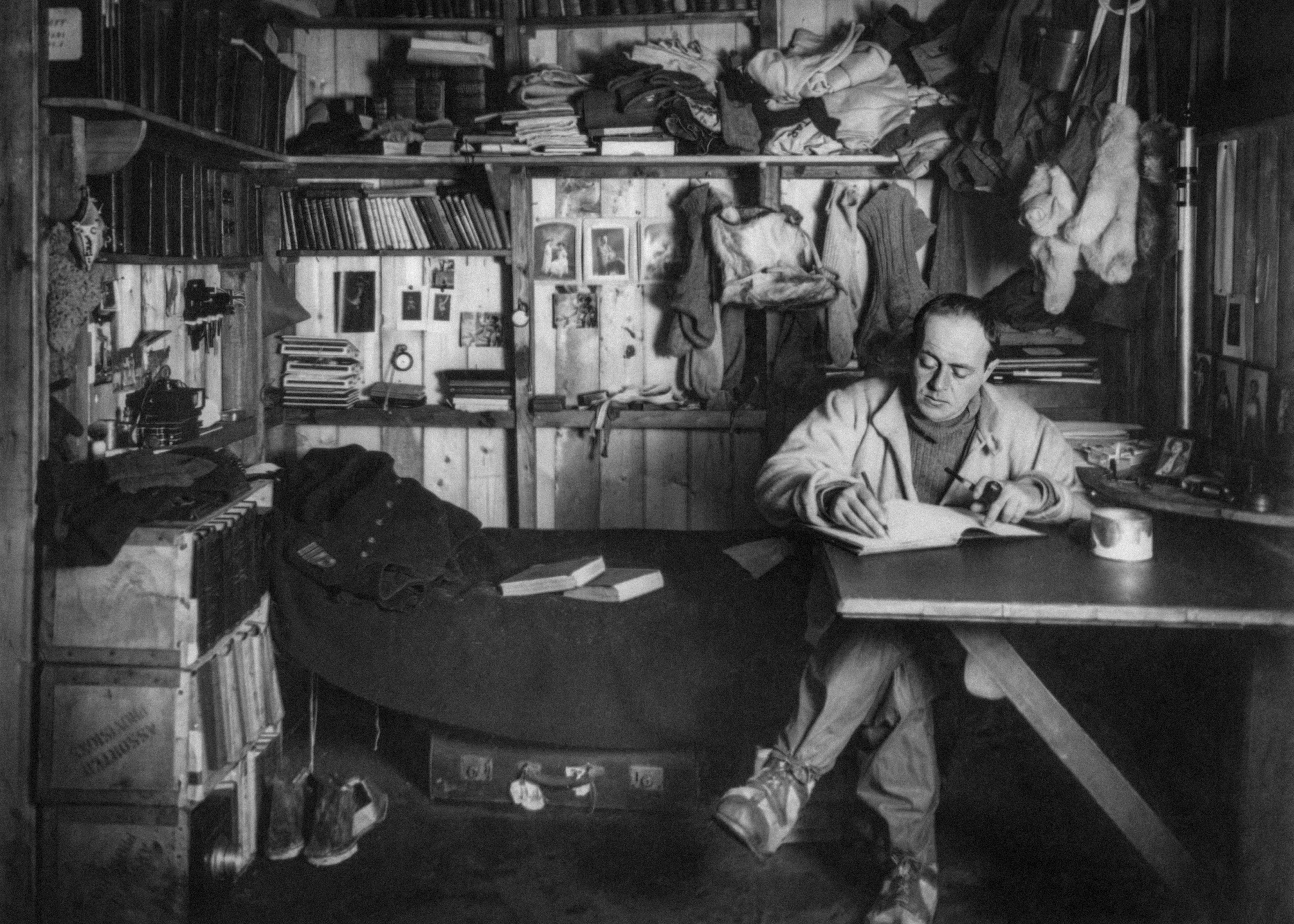

Such were the perils of Antarctic photography a century ago. And as Scott was watching Ponting with his ‘clear blue eyes’, Ponting was studying Scott too. Summer passed into autumn and then the winter of 1911 was spent at Cape Evans. All the time the date was drawing ever closer for Scott's attempt on the South Pole.

The expedition's leader spent much of his time in the cramped den that doubled as his office and bedroom. On 7 October, a few months before Scott’s departure, Ponting captured this picture (below) of him at his writing desk. Ponting was very proud of this photograph of the famed Polar adventurer. Knowing that Scott would be dead within six months adds to its poignancy today. The portrait, Ponting felt, ‘had captured something of the leader in it.’ •

All the black and white Public Domain photographs in this Viewfinder gallery have been meticulously restored from a high resolution digital scan from their original source. Share and use these remastered high resolution black & white historical pictures, for free, with Unsplash.

This Viewfinder feature was originally published March 29, 2024.

Further Reading

Herbert George Ponting, The Great White South, or, With Scott in the Antarctic (Duckworth: London, 1923)

Herbert George Ponting, With Scott to the Pole: the Terra Nova expedition, 1910-1913 (Bloomsbury: London, 2004)

H. J. P. Arnold, Photographer of the World: The Biography of Herbert Ponting (Hutchinson: London, 1969)

Ann Savours (ed.), Scott's Last Voyage: Through the Antarctic Camera of Herbert Ponting (Praeger Publishers: New York, 1975)

Anne Strathie, Herbert Ponting: Scott's Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker (The History Press, Cheltenham, 2021)

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store