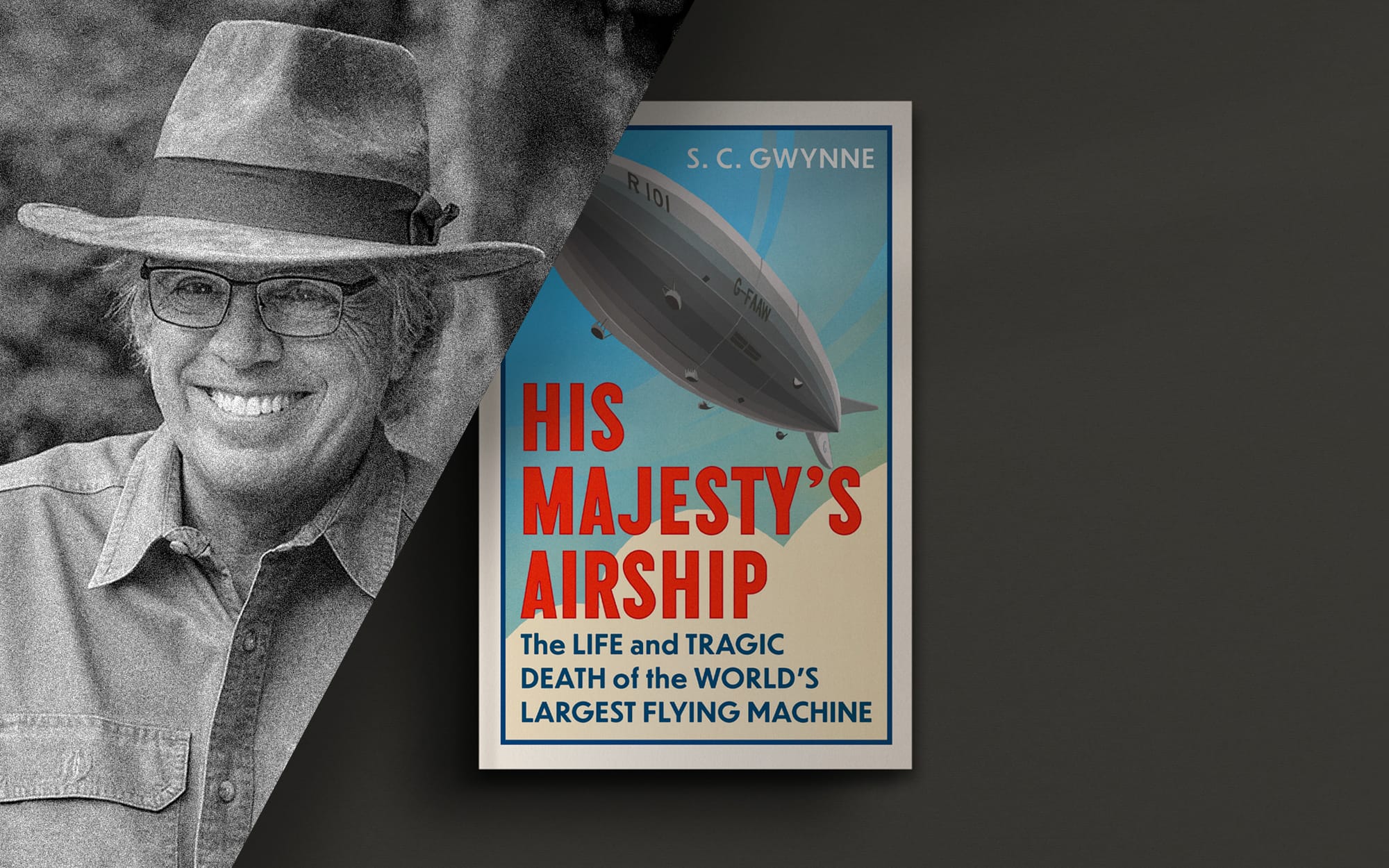

His Majesty’s Airship with S.C. Gwynne

S.C. Gwynne on the world’s largest flying machine

A century ago airships were among the most exciting symbols of modernity. They were huge contraptions that were lifted by hydrogen and filled with romance. For a generation of politicians, inventors and scientists they signalled a new period in history — a time when humans would finally master the skies.

The problem was that this dream never quite squared with reality. In his gripping new book, His Majesty’s Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World's Largest Flying Machine, the New York Times bestselling author S.C. Gwynne takes us back to the feats and follies of the airship era.

Unseen Histories

Airships seem to belong to some parallel H.G. Wells-inspired universe rather than our own. But for a few decades in the early twentieth century they really were regarded as a serious new technology. Can you sketch the span of the ‘Airship Era’ for us please?

S.C. Gwynne

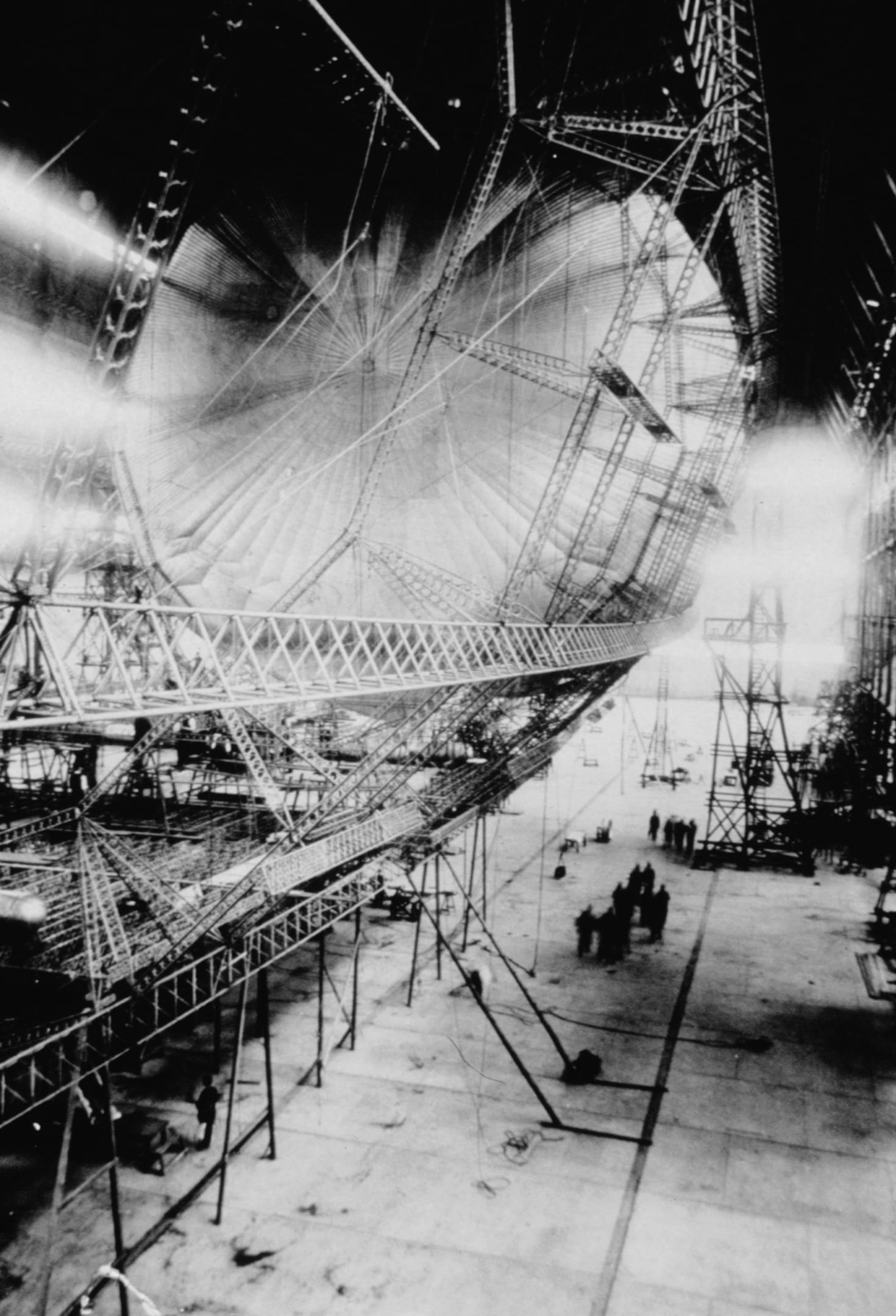

We might call it more precisely the ‘rigid airship’ era, since we are talking about huge structures framed by steel and covered by linen that contained giant gasbags. These are not balloons or blimps. Count Ferdinand Von Zeppelin built the first one in 1900, and later his zeppelins bombed European cities in World War I. The British and Americans later developed their own airship programmes. All were, ultimately, failures. The last giant airship flew in 1939, so the entire era lasted about 40 years.

Unseen Histories

There is a huge aesthetic appeal to an airship, but they were originally used as machines of terror during World War One. Is this right?

S.C. Gwynne

Count Von Zeppelin had always seen them as weapons of war. He dreamed of raining fire and death on London and Paris. In the service of the German war machine, his zeppelins became the world’s first long-range bombers, first weapons of mass terror. They introduced mankind to the notion that it could be obliterated from above by something other than a thunderbolt.

‘Rigid airships were a bad idea. They started as a bad idea, and finished as a bad idea. People are familiar with the famous video of the Hindenburg going up in a hydrogen-fuelled fireball. What people don’t know is that there were probably 75 such fireballs.’

Unseen Histories

Airships were developed around the simple idea that hydrogen is the lightest element on Earth. This might have been good science but little else about them was quite as sound. You write about their fragility. Was it true that the highly flammable hydrogen was often stored in ultrathin bags made from cattle intestines?

S.C. Gwynne

Yes, R101’s [the ill-omened British airship that is the subject of Gwynne's book] 5.5 million cubic feet of hydrogen were stored in large gasbags made of cattle intestines backed by a thin layer of cotton. They were are fragile as they sound. Some of them were 10 stories high. They looked like giant cheese wheels.

Unseen Histories

The decades that brought the airship were also the years of the first fixed-wing aeroplanes. What advantages did these contraptions possess over biplanes like the Sopwith Camel?

S.C. Gwynne

They could carry much more weight – R101 could lift 90 tons of cargo and passengers – and they were far better adapted to long range travel. Airplanes needed many fuel stops. R101 could fly direct to Egypt from London.

Unseen Histories

Piloting an airship must have required great courage. You write revealingly about the culture of the 1920s, which prized acts of reckless bravery. Can you give us a few examples of this?

S.C. Gwynne

A better example comes from the late teens. In 1919, after World War I had ended, found itself with a surplus military airship that had been modelled on the legendary zeppelin ‘height-climbers’ – built to evade British fighter planes. The name of the ship was R34. The boffins in Whitehall decided it would be a good idea to fly her across the Atlantic, even though R34 was not built to do any such thing. The result was the first east-west crossing by air of the Atlantic, and the first double-crossing. The flights were full of near crashes. The pilot, Herbert Scott, was at that moment the most celebrated aviator in the world.

Unseen Histories

Your chapter titles tell a story in themselves: ‘Brief History of a Bad Idea’; ‘Flying Death Trap’; ‘The Idea That Would Not Die’. Was the history of airships really so littered with disasters.

S.C. Gwynne

Rigid airships were a bad idea. They started as a bad idea, and finished as a bad idea. People are familiar with the famous video of the Hindenburg going up in a hydrogen-fueled fireball. What people don’t know is that there were probably 75 such fireballs. Airships were really only good in light weather and light winds.

Unseen Histories

A central figure in your book is Christopher Birdwood Thomson, the Secretary for Air. He is little remembered today but in His Majesty’s Airship he seems like a character straight out of an Evelyn Waugh novel. Can you tell us a little about him?

S.C. Gwynne

Thomson was man with a towering ambition to link the British empire through the new medium of the air. He was perfect for this job. He had spent his military career fighting in many of the main theatres of the Empire. His family consisted of five generations of mostly important military figures in the Indian Raj. Thomson was the main driver behind the ill-fated Imperial Airship Scheme, and lost his life in his attempt to prove that it could work.

Unseen Histories

It is Thomson who brings us to the central airship in your book: R101. This was seen as a new airship for a new decade (the 1930s). What was its purpose?

S.C. Gwynne

Its purpose was the fly from England to India and show how the vast empire – the largest in human history, covering 25 percent of the globe – could be linked together.

Unseen Histories

In His Majesty’s Airship you intersperse your account of the fateful voyage of R101 with flashbacks that delve into the broader history of the subject. Was this structuring device clear in your mind at the beginning or did it emerge over time?

S.C. Gwynne

That was my idea from the beginning. I wanted to keep the reader close to the main action—the doomed 7-plus hour flight over the English Channel from England to France. The backstory fits nicely in behind the present-time action 𖡹

His Majesty's Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World's Largest Flying Machine

Oneworld Publications, 12 October, 2023

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0861547081

"A Promethean tale of unlimited ambitions and technical limitations, airy dreams and explosive endings"

– Wall Street Journal

In 1929, the R101 was the largest object ever to take to the air. It was meant to dazzle the world with cutting-edge technology and awesome size. Better than a plane, more luxurious than an ocean liner, the R101 would connect the furthest reaches of the British Empire, tying together far-flung dominions at a time when imperial bonds were fraying. It was, however, not to be.

The spectacular crash of the British airship R101 in 1930 changed the world of aviation forever. Most have heard of the fiery crash of the Hindenburg, a German ship that went down in New Jersey seven years later. But the story of R101 and its forty-eight victims has largely been forgotten.

His Majesty’s Airship recounts the epic narrative of the ill-fated airship and her eccentric champion, Christopher Thomson. S. C. Gwynne brings to life a lost world of aviators driven by ambition, and killed by hubris.

"I loved every page of this book. Even though we’re aware of R101’s tragic fate from the beginning, Gwynne still delivers an intensely dramatic story"

– The Times

"Captivating... Gwynne spins a rich tale of technology, daring and folly that transcends its putative subject. Like any good popular history, it’s also a portrait of an age"

– New York Times

With thanks to Kate Appleton. Author Photograph © Kenny Braun