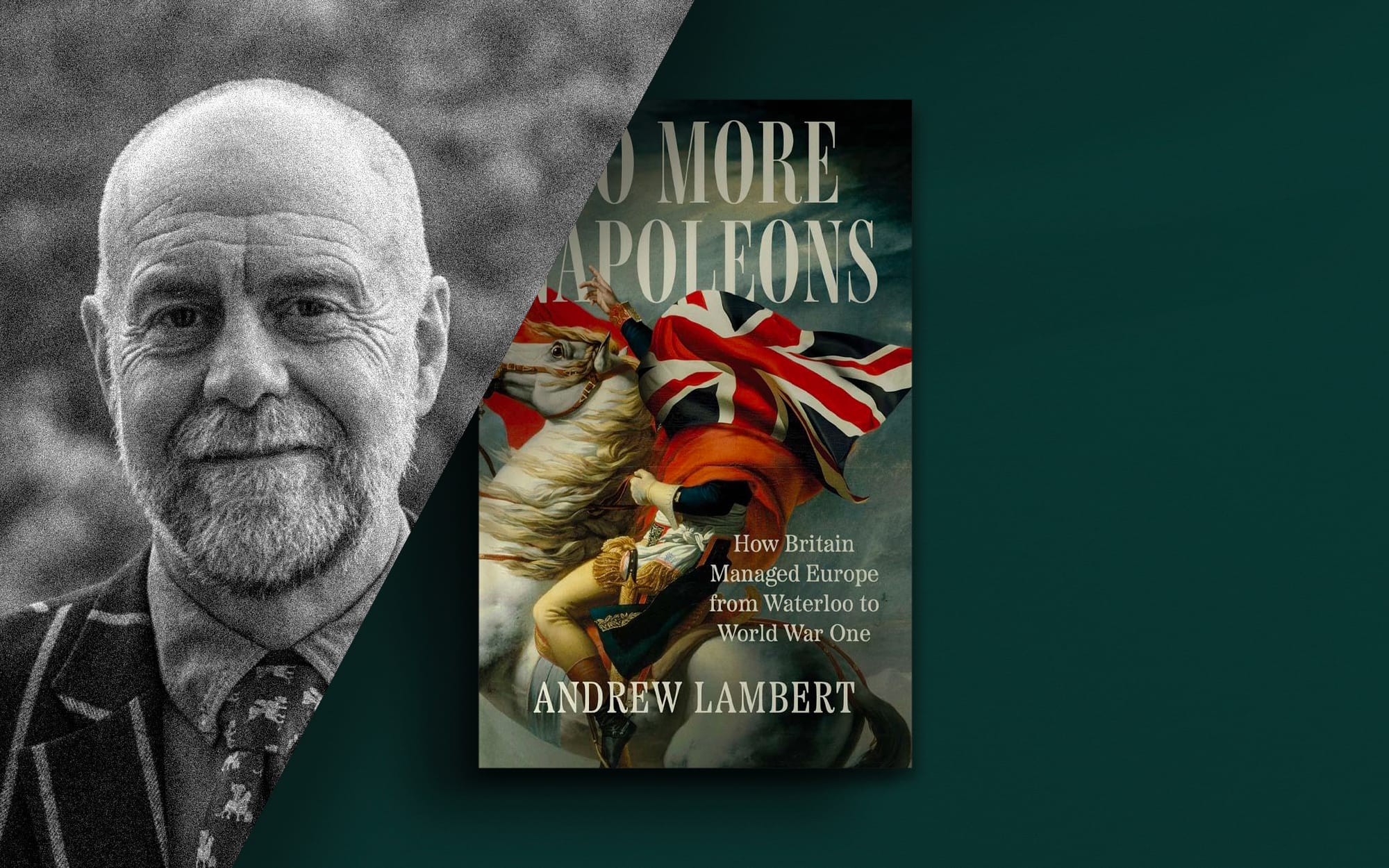

How Britain Managed Europe from Waterloo to World War One

Andrew Lambert's new book explores an inspired century of statecraft

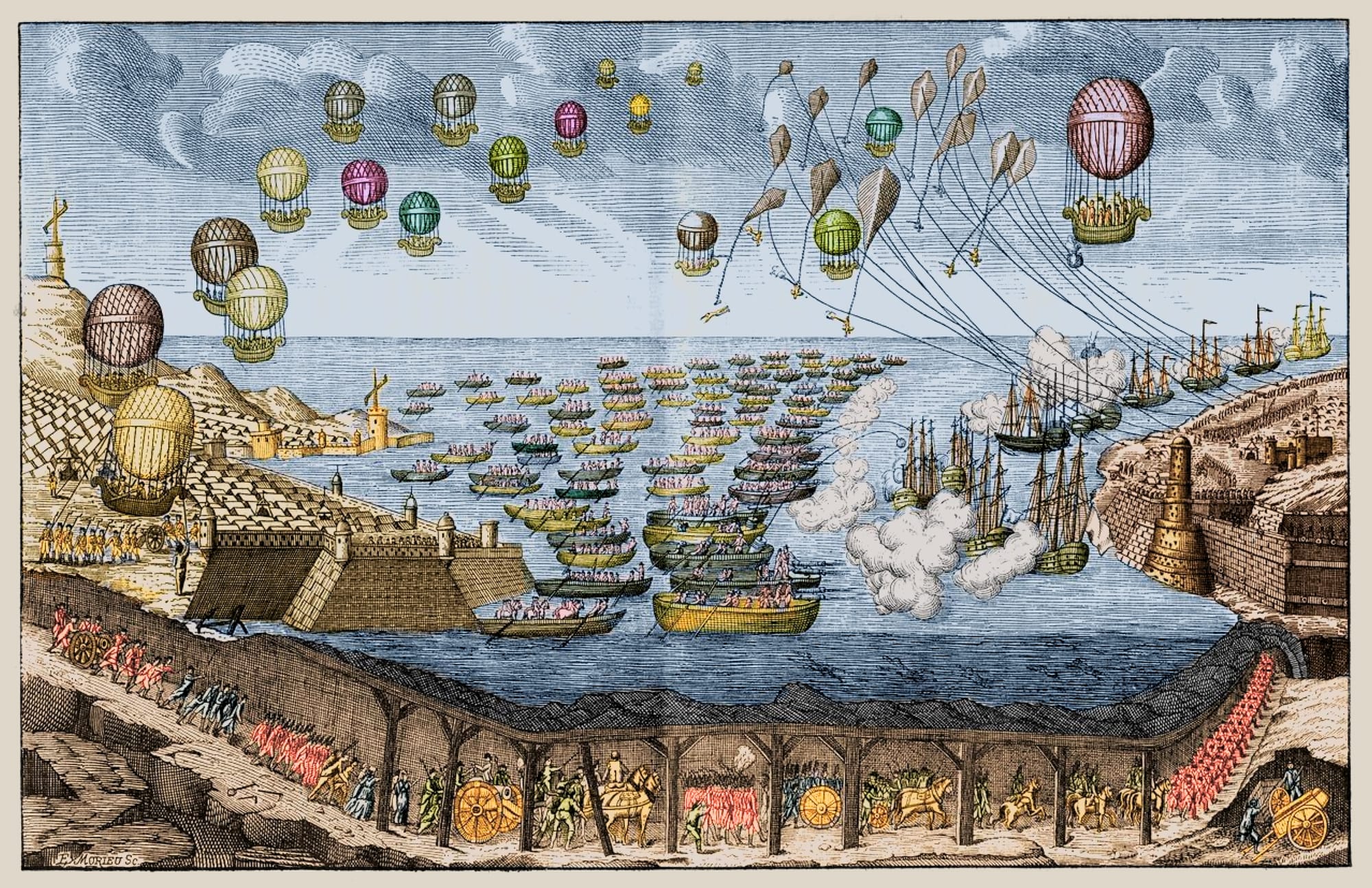

As the nineteenth-century opened, many Britons believed themselves to be facing an existential crisis. Just a short distance away Napoleon's mighty army gathered around Boulogne on the French Channel coast.

The terror of that historical moment was very real, Professor Andrew Lambert explains in this interview, even if the threat was 'hyped up'.

In his new book, No More Napoleons, Lambert investigates how British politicians spent the next century ensuring that no such terror was ever felt again.

Questions by Peter Moore

Unseen Histories

No More Napoleons is a book about subtle and very effective statecraft in the century between Waterloo and July 1914. What drew you to write it?

Andrew Lambert

I have long thought that conventional explanations of the British decision to enter the First World War were flawed, largely ignoring the failure to use forceful diplomacy, backed by a naval demonstration to demand Germany step back from invading Belgium.

It was clear to me that the neutrality of Belgium was vital British interest, having been created in 1839 to deny the Scheldt Estuary, the obvious starting point for a French and more recently German attempt to invade.

The Scheldt was the only place on the north-west coast of Europe where a large invasion fleet could be assembled out of range of naval gunfire. Belgium had been part of France between 1793 and 1814, it was the reason why Britain went to war in 1793, shaped the peace process of 1814-15, and explained why Waterloo was fought.

Unseen Histories

Your study opens directly after a period at the opening of the nineteenth-century, called ‘The Great Terror’, when Britain felt the severe threat of invasion from Napoleon’s France. How deep was this terror?

Andrew Lambert

The threat of an invasion by France, the long-term enemy, was a powerful message to unify the country for a ‘total’ war against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France – one which lasted 21 years with a brief interlude of hostile peace in 1801-03. The anxiety was hyped-up by the government, to secure increased taxes and recruit more sailors and soldiers.

It was not a likely outcome; France lost every naval battle. Little wonder Nelson became the national hero, he saved the nation. He would be joined by Wellington who ended the wars, and secured Belgium against the last French invasion at Waterloo.

Invasion threats were a distraction, keeping British forces tied to home defence while France conquered Europe. Nelson and Wellington discussed this issue in September 1805.

Unseen Histories

Despite this perception, you emphasise that pre-Trafalgar Napoleon was in no position to launch an invasion of Britain and that his troop movements were actually a feint. Is this an accepted view among scholars today?

Andrew Lambert

There is still a tendency to assume Napoleon was serious – a version of events that treats Trafalgar as the battle that saved the nation from disaster.

However, the evidence to the contrary is compelling. Nelson’s last battle at Trafalgar was fought to stop Napoleon’s invasion of Sicily, not England – the emperor had ordered the Franco-Spanish fleet into the Mediterranean. Meanwhile the main French fleet, based at Brest, which was meant to escort the invasion, was blockaded in port by a larger British fleet, led by Nelson’s friend Sir William Cornwallis, the unsung hero of the 1805 campaign.

Napoleon used the invasion story to disguise his real plan, to invade Austria. The army he assembled at Boulogne marched south to glory at Austerlitz. Had it put to sea it would have been destroyed.

Unseen Histories

You mention Lord Fisher’s poetic view of ‘strategic keys’ that could unlock the nineteenth-century world. Then there was the Scheldt, a significant estuary that flows through the Low Countries. What was the draw of this?

Andrew Lambert

The Scheldt was not one of Admiral Sir John Fisher’s ‘keys’ - these were a chain of strategic bases that combined major naval centres with commercial harbours – the twin pillars of Britain’s global power.

The ‘keys’ were all located on narrow straits, including the Suez Canal, passages or chokepoints which British commerce and warships had to use to maintain national security and imperial prosperity. He identified them in 1904, as First Sea Lord – the head of the Royal Navy based at the Admiralty in Whitehall – as he began rebuilding the fleet for global operations.

They were Singapore, Cape Town, Alexandria, Gibraltar and Dover. Dover would support fleets stationed off the Belgian coast, securing British control of the English Channel and preventing any invasion fleet leaving the Scheldt Estuary. It fulfilled that role in two world wars.

Unseen Histories

The claim that ‘Belgian neutrality’ is central to British security is one that many will associate with July 1914. But wasn’t this a maxim developed by Lord Castlereagh? Or does it go further back than this?

Andrew Lambert

The critical role of what we now call Belgium in British strategy predates Britain, and Belgium. England’s first ‘strategic’ naval battle was fought at Sluys, then a harbour on the Scheldt, in 1340. The English fleet destroyed a French invasion fleet, ensuring the ‘Hundred Year’s War’ was fought in France, not England.

Belgium was created in 1839, by the Treaty of London, to deny this critical area to France, or any other major power that might wish to attack Britain. This process was begun by Wellington in 1830, as Prime Minister, reflecting Waterloo and his work to secure the region after 1814.

The Government of 1814-15 understood that while France occupied Belgium and the Scheldt Estuary Britain would be forced to maintain defence spending at wartime levels. This was settled with the allies before the Congress of Vienna.

Unseen Histories

Out of this recognition grows what came to be known as ‘the Wellington System’, an example of what political scientists call ‘off shore balancing’. Why is this so connected with Wellington?

Andrew Lambert

Wellington shaped a strategic system to support the 1815 territorial settlement, to address British concerns that a profoundly unstable France might seek to recover Belgium.

France had eight more or less violent changes of political system between 1814 and 1871, including three Empires, two monarchies, a constitutional monarchy and two Republics.

After 1871 those anxieties decreased, but by 1900 a new ‘Napoleon’ had appeared, the German Kaiser Willhelm II, his imperial ambitions and naval build-up, added to an already dominant army rendered the Low Countries insecure.

In 1907 the British Army was reorganised to support a five-division force for Northern Europe, focussed on the neutrality of Belgium, and the security of Antwerp. The Treaty of London of 1839 was the only obligation to act in Europe that Britain had in 1914.

Unseen Histories

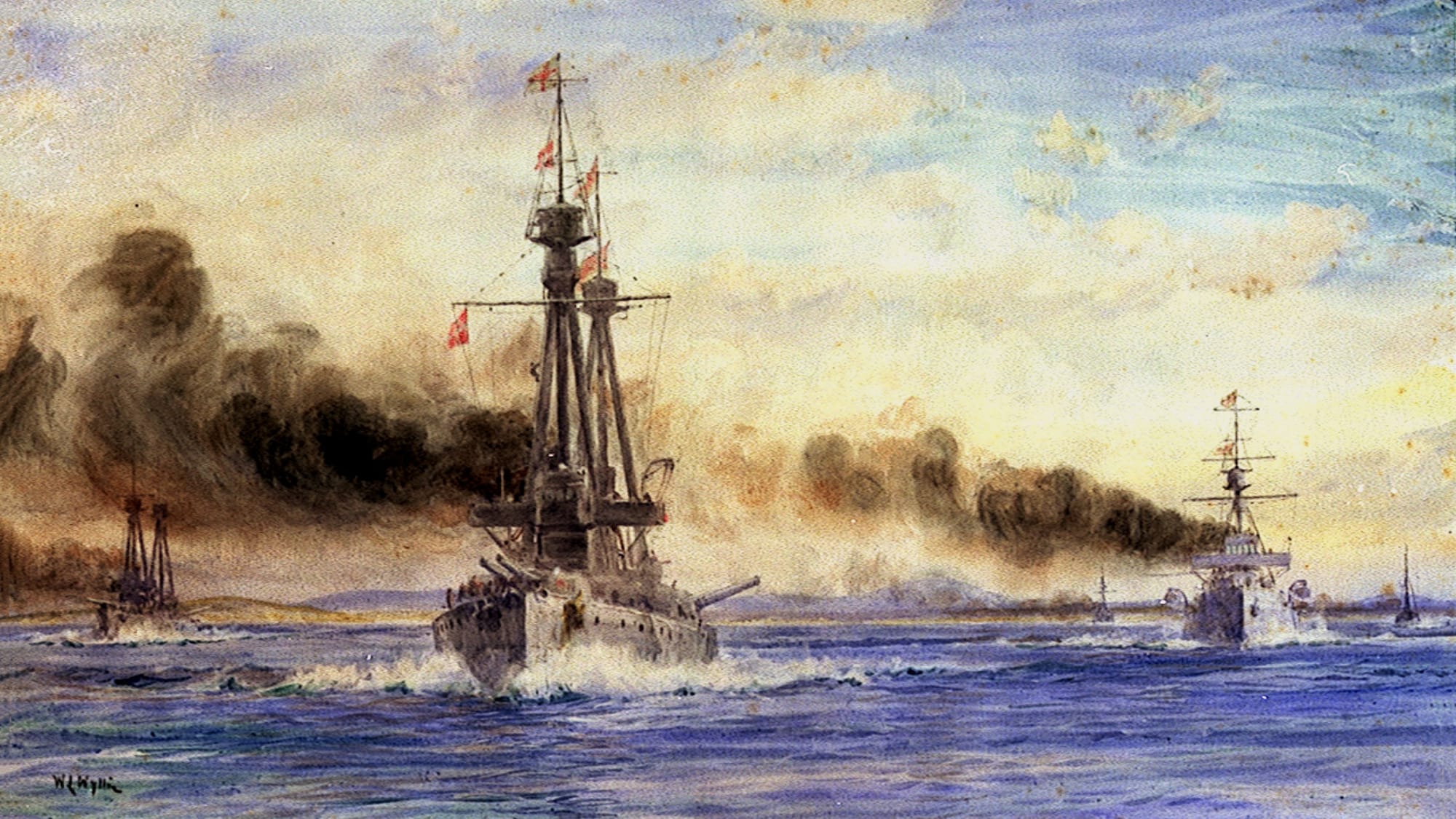

The nineteenth-century was a time of huge technological progress. You note how Nelson’s navy developed into a force of steam ships over the decades that followed. What effect did this change have on the Wellington System?

Andrew Lambert

Wellington’s ‘System’ remained relevant throughout the period after 1815. In 1830 he accepted that steam propulsion and shell firing artillery added new capabilities at sea, ideal for attacking coastal positions, landing troops and capturing merchant shipping.

To meet this challenge Britain funded massive harbour projects at Dover, Portland, Holyhead, Dunleary, Alderney and Harwich, using the latest civil engineering methods to ensure they were accessible 24/7.

After 1860 larger steamships, built of iron and steel increased the ability to move armies by sea, while long-service professional naval ratings were recruited to operate complex technologies. If it maintained a powerful, modern fleet and secure bases Britain could dominate the Narrow Seas, rendering an invasion even less likely than in 1805. By 1900 naval planning envisaged using an economic blockade to defeat a continental power, most likely Germany, that invaded Belgium.

Unseen Histories

Your study shows thoughtful policymakers executing a subtle strategy. Apart from Castlereagh and Wellington, did you identify any others whose judgment impressed you?

Andrew Lambert

I would highlight Prime Minister Lord Liverpool, who led the government that won the war, and the peace. A ‘Brexiteer’ by conviction, he had been present at the storming of the Bastille - he worked for a balanced, stable and cost-free Europe.

Admiral Sir Thomas Byam Martin provided critical strategic and technological leadership and advice across the period 1814-1854. Lord Palmerston, as Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister carried the ‘Wellington System’ into the 1860s, using a combination or public rhetoric, diplomacy and force to maintain British interests.

I would also highlight the post-war generation of military professionals, I focussed on the Codrington brothers General Sir William and Admiral Sir Henry, who recognised the critical need to harmonise Navy and Army to shape a truly ‘British’ way of war as they fought in the Crimean War (1854-56).

Unseen Histories

Recent books like Philip Stephen’s Britain Alone portray modern Britain as being undermined by a lack of clarity when it comes to identity and foreign policy. Having written No More Napoleons, are you left with this impression too?

Andrew Lambert

The fundamental issue is one of culture, and the problem set in with the end of empire, which had defined Britain for two centuries as a global economic power with a hegemonic navy.

This is common problem for many former imperial states. The drift from VJ Day to 2025 is obvious - losing merchant shipping, shipbuilding, and a powerful manufacturing economy, while sacrificing a global navy, reflected an increasing lack of direction.

Leaving Cold War era security to NATO was sensible but lacked the emotional buy-in of a national effort. It was no accident that the Falklands Crisis of 1982 galvanised the nation, referencing less complex times, including the Armada of 1588.

Suddenly the nation had a shared sense of purpose, and some pride in its history. Since then bland consensus and petty politics have left the British without a sense of national purpose. Other countries have been better at creating new narratives •

This interview was originally published August 28, 2025.

No More Napoleons: How Britain Managed Europe from Waterloo to World War One

Yale University Press, 24 June, 2025

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0300275551

How, for just over a century, Britain ensured it would not face another Napoleon Bonaparte–manipulating European powers while building a global maritime empire.

At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, a fragile peace emerged in Europe. The continent's borders were redrawn, and the French Empire, once a significant threat to British security, was for now cut down to size. But after decades of ceaseless conflict, Britain's economy was beset by a crippling debt. How could this small, insular seapower state secure order across the Channel?

Andrew Lambert argues for a dynamic new understanding of the nineteenth century, showing how British policymakers shaped a stable European system that it could balance from offshore. Through judicious deployment of naval power against continental forces, and the defence strategy of statesmen such as the Duke of Wellington, Britain ensured that no single European state could rise to pose a threat, rebuilt its economy, and established naval and trade dominance across the globe.

This is the remarkable story of how Britain kept a whole continent in check–until the final collapse of this delicately balanced order at the outset of World War One.

“With the future of NATO being questioned as never before, policymakers should read this superb book as a masterclass in the vital areas of strategic acuity, domination of the oceans, and the deployment of hard power. It was no coincidence that Britain managed to deter attack from any major power for almost a century after Waterloo, and Andrew Lambert shows how it was done by far-sighted statesmen in an era of intense Great Power rivalry”

– Andrew Roberts, author of Churchill: Walking With Destiny

With thanks to Heather Nathan and James Williams.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store