Excerpt: A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions

This excerpt from A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions investigates the story of seeing from the evolution of eyes 500 million years ago to the present day.

Jam-packed with fascinating stories, facts and insights and impeccably researched, this excerpt from A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions investigates the story of seeing from the evolution of eyes 500 million years ago to the present day. Time after time, it reveals, inventions that changed how people saw the world ended up changing it altogether.

With an exclusive foreword for Unseen Histories by Susan Denham Wade

When the internet meme #thedress set the online world on fire in 2015 I was inspired to investigate the highly subjective art of seeing. If two people in the same time and place in the 21st century could see the same thing differently, I wondered, how did people living hundreds or even thousands of years ago see their worlds? This took me on a journey back through time to the very origins of life on Earth.

Seeing, it turns out, has a very ancient pedigree and may in fact have been the catalyst for the evolution of the animal kingdom. When early humans appeared a million or so years ago they started a process of augmenting their natural vision with technology, beginning with fire and continuing through art, mirrors, writing, lenses, printing, artificial light, film and most recently the smartphone.

With each visual invention humankind changed the way they see the world and, in turn, changed the world they see. And in doing so, they gradually promoted vision at the expense of our other senses. As we enter the second decade of the smartphone era, and our lives are increasingly channelled through illuminated screens, I pose the question: have we gone as far as the eye can see.

⇲ A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions is essentially a meta-analysis of research from at least a dozen scientific fields: anatomy, anthropology, archaeology, art history, astronomy, cultural studies, film theory, history, neuroscience, palaeontology, physics, psychology, sociology, theology, and zoology, as well as popular culture. — Susan Denham Wade

Nature’s Pencil: Photography

An excerpt from A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions

Like London buses, similar inventions often appear at the same time. We can put this down to zeitgeist, a nineteenth-century German concept meaning the ‘spirit of the age’ that seems to make some inventions almost inevitable. As the pioneering historian of psychology Edwin Boring put it in 1950:

not only is a new discovery seldom made until the times are ready for it, but again and again it turns out to have been anticipated, inadequately perhaps but nevertheless explicitly, as the times were beginning to be ready for it.

By the early 1800s, the Western world was beginning to be ready for photography. Developments in science, philosophy, art, society and industry combined to foster a spirit of the age in which several actors, unknown to one another, started looking for ways to combine optics and chemistry and ‘fix’ images automatically.

Europe, Early 1800s

For two centuries after the invention of the telescope, interest in observing and chronicling the workings of nature continued to rise. Scholarly endeavours placed observation and direct experience at the forefront of knowledge and ideas. Sir Isaac Newton’s insights in the late 1600s showed that the natural world was not guided by invisible, animate and sacred spirits, but was rather a giant, quasi-mechanical system governed by a series of rules and laws that could only be understood – and indeed were slowly being revealed – by keen observation and methodical experimentation. Philosophers such as Descartes and Locke had overturned the classical view that certain innate truths exist. Knowledge was not vinnate, the newly modern scientists believed, but must be acquired by direct experience and sensory perception. I see, therefore I know.

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were times of enquiry and exploration. Scrutiny, surveillance, investigation, classification and analysis of nature were taking place all over the world – from the mapping of the stars made possible with enormous new telescopes, to ambitious geographical and geo-logical surveys, to the taxonomy of plants, animals and insects, to studies of the invisible world with microscopes. The appetite to see and record the physical world was voracious.

Intrinsic to the need to experience and observe was travel, and this took place on a grand scale during this period. The great new colonial powers sent fleets of ships around the world’s oceans in pursuit of trade, and overland expeditions into the interiors of the Indian sub-continent and Africa. Newly independent Americans were exploring and surveying the continent, pushing ever further west against considerable – but ultimately unsuccessful – indigenous resistance. In Europe, wealthy and aristocratic young men – and, sometimes, women – routinely embarked on the Grand Tour, a lavish precursor to the modern gap year.

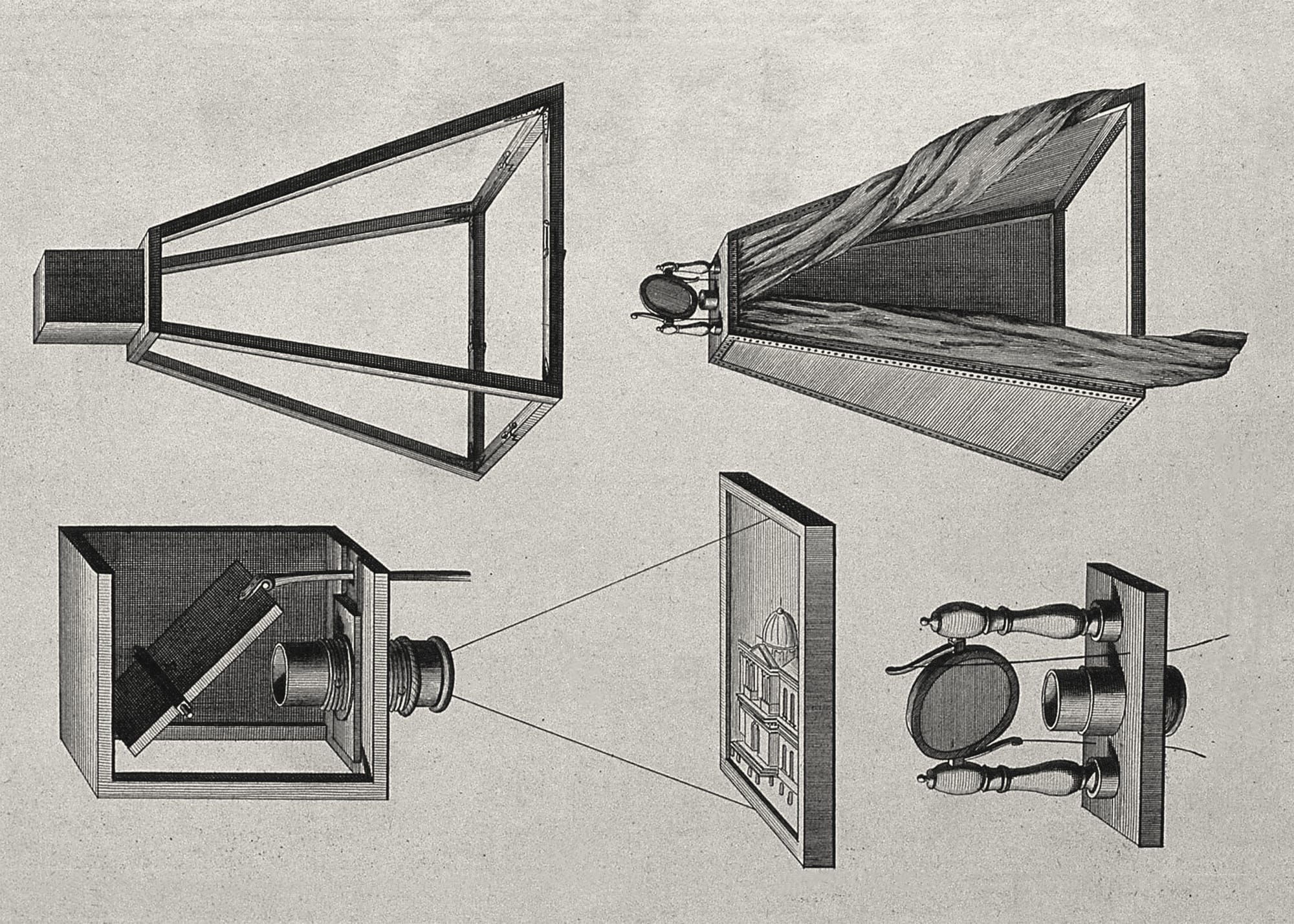

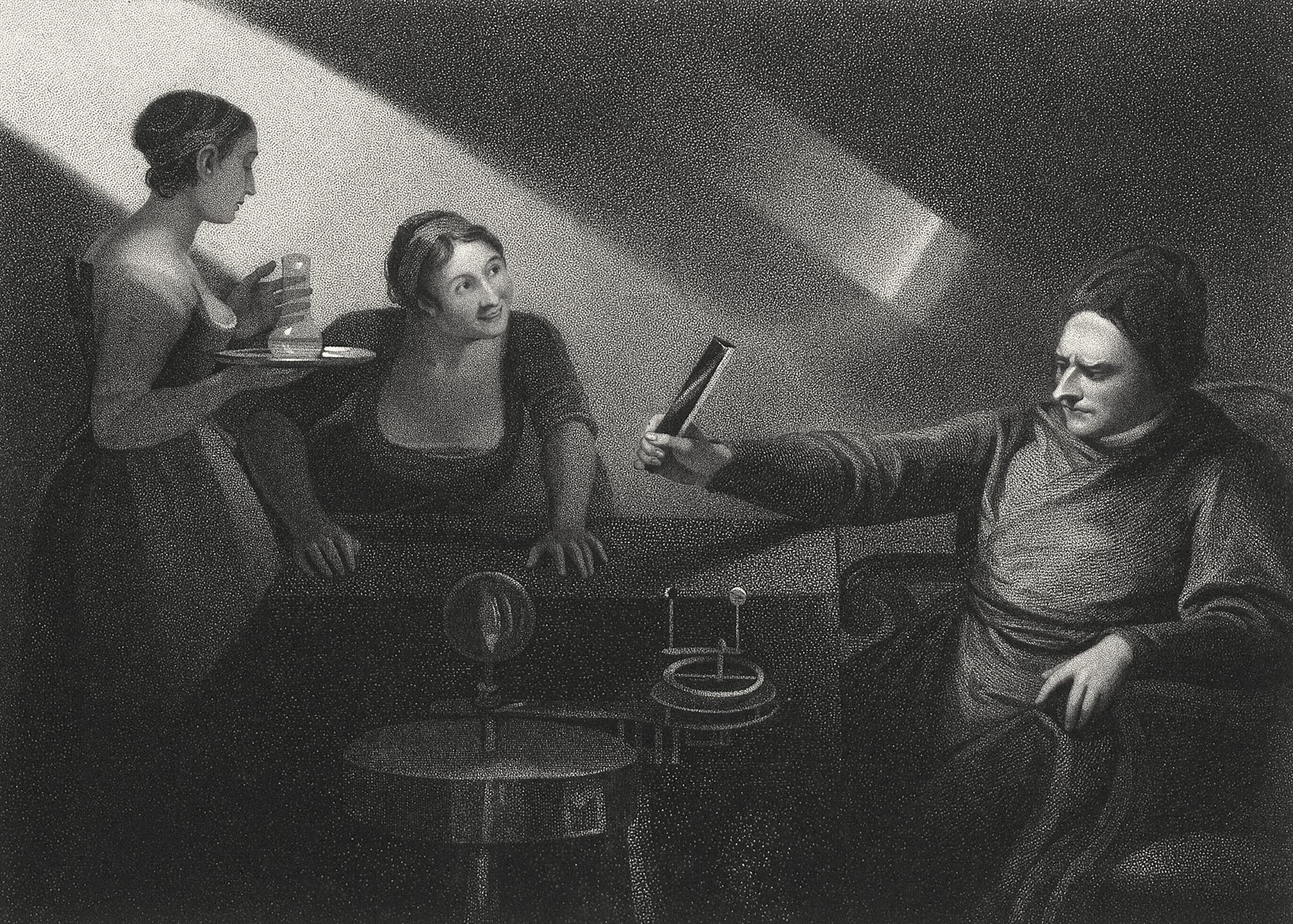

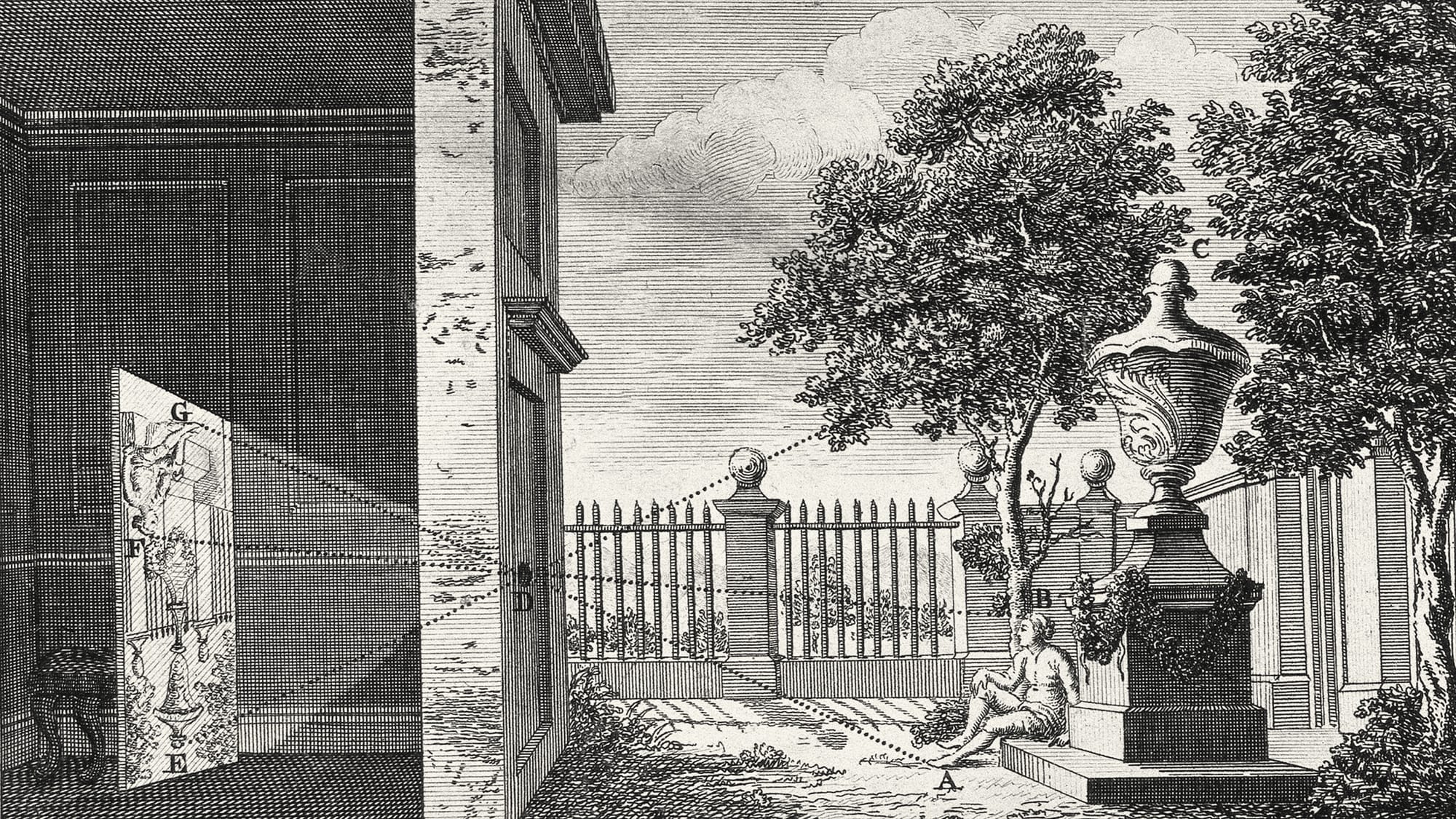

All this observing drove a requirement to record what was seen. The options available were sketching, drawing and painting, and topographical, scientific and botanical illustration were popular career paths for artists at this time. Rigorous depiction was all very well if one were a talented draftsman, but not all travellers were so gifted. Scholars and amateur enthusiasts – as well as artists – turned to the camera obscura to help them capture accurate representations of landscapes and objects. Just to remind you, the camera obscura is a natural optical phenomenon whereby the image of a brightly lit scene can be projected through a small hole onto a surface in a darkened space.

The original camera obscuras were actual rooms, but by the eighteenth century there were portable versions available. The so-called Royal Delineator was a mahogany box with a telescopic viewfinder fitted with two convex lenses, a tilted mirror to redirect the image to the top of the box, and a lens at the top to enlarge the image on the drawing surface. It received a king’s patent around 1780 and was reputedly favoured by famous painters including Canaletto and Sir Joshua Reynolds as well as wealthy amateurs. Another contraption known as the ‘field camera’ perched on top of a small, dark tent in which the artist sat tracing the image projected and reflected down onto a piece of paper.

In 1806 an Englishman called William Hyde Wollaston, despairing at his lack of ability to capture the grandeur of the Lake District on paper, patented a new optical drawing aid he called the camera lucida. This was an elegantly simple and highly portable device that used a small prism suspended on a stand to reflect the image being observed in such a way that it appeared to float over the paper like a ghost, allowing the user to trace the subject in as much detail as they chose. It quickly became the preferred instrument to aid observational drawing and was used by artists and amateurs all around the world for the first half of the nineteenth century.

Around the same time as Wollaston launched his device, the art world was experiencing a quiet revolution. With some notable exceptions, landscape painting had until now been seen as the poor relation of art, the precinct of jobbing topographers recording monuments for the tourist trade and country seats for the vanity of provincial squires. A Suffolk countryman called John Constable (1776–1837) and his Londoner contemporary J.M.W.Turner (1755–1851) changed that view and, in the process, paved the way for more radical artistic changes in the second half of the nineteenth century. Both artists approached nature in all its forms – embracing such mundane details as ‘willows, old rotten banks, slimy posts’ as well as the more dramatic atmospheric effects of light and weather – as a subject worthy of their full attention. This was a departure from traditional landscapes, where it was typically man’s interventions in nature that took centre stage. Constable and Turner used pioneering techniques of colour, brushwork and composition to represent nature as they saw it instead of as the artistic academies deemed it. They painted with the eye rather than the mind.

In 1796 another German used chemical reactions to devise a printing technique he called lithography, meaning drawing with stone. Lithography could reproduce images faster and more cheaply than earlier etching or woodblock printing, and made graphic art and pictures widely available to ordinary people for the first time. A new market for printed pictures reproduced from paintings or made especially for the purpose of printing developed to serve the middle classes. Reproduced images became commonplace for the first time.

In manufacturing, the Industrial Revolution was well under way, and more and more traditional tasks and trades were being industrialised and automated by the new machines. Could the artist’s craft go the same way?

The currents of scientific, artistic, industrial and social change were mixing and converging. The zeitgeist was slowly forming an idea that hung in the atmosphere like the fragmentary memory of a dream: could an image be taken directly from life and captured, frozen and fixed forever?

Paris, August 1839

On the afternoon of 19 August 1839, more than 200 people waited in the courtyard in front of the imposing pillared entrance to the Institut de France, on the left bank of the Seine facing the Pont des Arts and the Louvre. The crowd was the overflow that had accumulated since the last seat inside the building had been taken hours earlier. Inside, members of the Academies of Beaux-Arts and of Sciences took their places in the centre of the main chamber, surrounded by the packed visitors’ stalls and overlooked by busts of France’s most distinguished contributors to art, science and philosophy. At the focal point of the room sat Messrs Daguerre, Niépce (junior) and Arago.

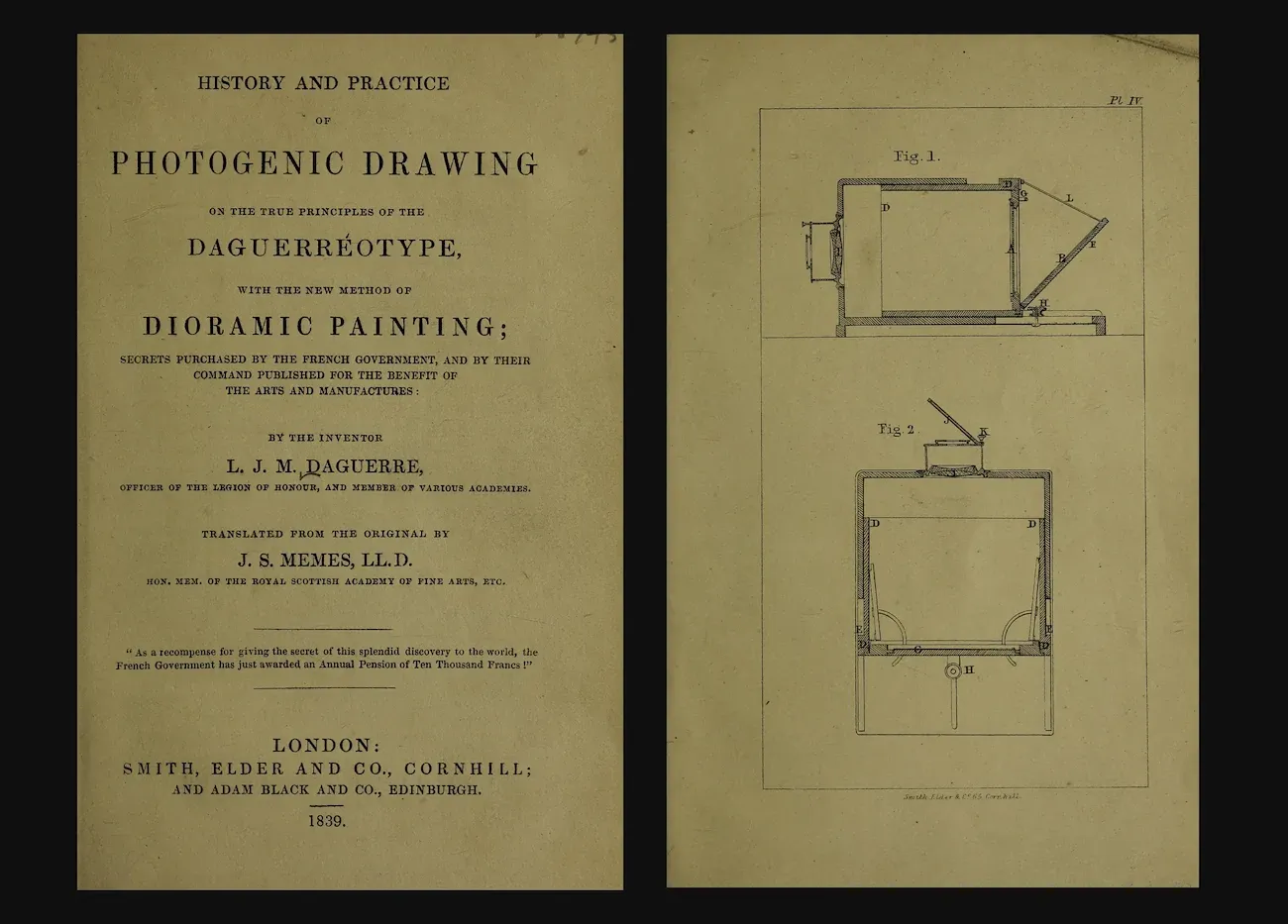

At three o’clock M. Arago rose and addressed the crowd. He described the history of the camera obscura and discoveries of the light sensitivity of various substances, the early experiments of Thomas Wedgwood, the achievements of Nicéphore Niépce in fixing the first permanent image from nature, and the further trials Daguerre had carried out after Niépce’s death.

Finally, M. Arago came to the part everyone was waiting for: the description of the daguerreotype process. In the event he gave a fairly abbreviated resumé, along with a promise to publish a full manual and present practical demonstrations soon. If the crowd were disappointed by the lack of detail, they didn’t show it. Even the stern Academicians cheered, and the announcement was widely reported in Paris the next day and London three days later.

Things moved fast from there. The daguerreotype process was made freely available to all thanks to the largesse of the French Government, but Daguerre had cannily retained a patent on the equipment required to execute it. By early September there were advertisements in the French press for the official daguerreotype manual, camera and plates. The manual was published in French on 7 September and within a week an English version was available in London.

The news crossed the Atlantic as fast as the newest steamer ship, the British Queen, could carry it. The French equipment licensee sent its agent, François Gouraud, to New York to stimulate interest and secure equipment orders. Demonstrations and exhibitions started appearing in big American cities within weeks, and newspapers and journals were full of discussion of the ‘new art’.

Worth a Thousand Words?

Photography appeared two years after the coronation of Queen Victoria, and came of age alongside the telegraph, the transatlantic steamship and the railway. Together these technologies sped up time and shrank the world. Messages could be sent across continents and even oceans in minutes, and people and things could move around the world as never before. And they did.

Nearly 3 million European immigrants arrived in the USA between 1840 and 1850, with many millions more to come in subsequent decades, and millions more Europeans moved to new colonies in South America, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. Within the USA, tens of thousands moved from the cities of the east coast to newly available farmland in the Midwest, while in Europe industrialisation and crop failures were driving people from the countryside into growing cities with their promise of work in large, gaslit factories.

Human dislocation was taking place on a massive scale. Did photography play a part in this? Photographs showed people what was at the other end of the line, and what they’d left behind. Loved ones could be captured on a little plate, packaged in a frame and kept close. Did this make it easier to leave them behind? Photographs created the illusion of presence: a ‘true’ likeness, rendered by nature. The likeness was a mirage of course, devoid of a body’s warmth, touch and characteristic smell, the sounds they made moving around and, most importantly, their voice. But the picture was something tangible, miraculous and, most importantly, present. We can be apart because we see each other.

And as photographs stood in for absent loved ones, the photographable – that is to say, visible – aspects of a person’s being assumed a new significance, over and above their other characteristics. The memory of the sound of a loved one’s voice, the grasp of their hand and the smell of their neck may fade over time, but the photographed face is never forgotten, even if that face is frozen in time.

Photographs captured what appeared to be an unmediated reality and were therefore assumed by many to be infallible envoys of truth... To this day there is a general belief that ‘the camera doesn’t lie’, despite the fact that photographs haven’t always delivered on their truthful promise. From the outset photographs were faked and staged to boost a particular cause or increase their dramatic effect. An 1895 newspaper article quipped: ‘Photographers, especially amateur photographers, will tell you that the camera cannot lie. This only proves that photographers, especially amateur photographers, can.’

Notwithstanding this sort of sophisticated scepticism, for most people, most of the time, photographs were considered accurate representations of reality and as such defined what ‘is’. As portraits they allowed ordinary people to immortalise the best version of themselves they could muster. As personal mementos they created and fixed memories and transported loved ones through time and space. In journalism, politics and advertising – all historically dominated by written or spoken words – the role of photographs evolved from illustrating text to verifying it, abbreviating it and, finally, superseding it altogether.

In 1911 a journalist, writing an article about journalism, used the phrase ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. A decade later an ad man, writing an article about advertising, upped it to ‘one picture is worth ten thousand words’, and added the entirely fictitious claim that the phrase was a Chinese proverb, hoping this would make people take it seriously. Given the relentless rise of images in advertising and elsewhere to their present ubiquity, and the general acceptance of the phrase as a truism, his strategy worked.

Henry Fox Talbot called photography a little bit of magic, realised. Humanity remains deeply under its spell ■

A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions

Flint Books (The History Press), 2 August 2021

RRP: £12.99 | ISBN: 978-0750997164

In 2015 #thedress captured the world’s imagination. Was the dress in the picture white and gold or blue and black? It inspired the author to ask: if people in the same time and place can see the same thing differently, how did people in distant times and places see the world?

Jam-packed with fascinating stories, facts and insights and impeccably researched, A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions investigates the story of seeing from the evolution of eyes 500 million years ago to the present day. Time after time, it reveals, inventions that changed how people saw the world ended up changing it altogether.

Twenty-first-century life is more visual than ever, and seeing overwhelmingly dominates our senses. Can our eyes keep up with technology? Have we gone as far as the eye can see?

"A remarkable achievement" – Stephen Fry

"Elegant, sweeping, and wholly fascinating tour through human history." – Peter Moore

"A wonderful, wide-ranging, totally gripping account of the evolution of seeing ... Well worth casting your eye over, if only to find out how - and why - you are able to do that." – Giles Coren

Susan: Inspirational texts that carried me through my fascinating (fascinated!) journey into the history of seeing include:

⇲ The Printing Press as an Agent of Change by Elizabeth Eisenstein (Cambridge University Press, 1980)

⇲ Eye and Brain: the Psychology of Seeing by Richard L. Gregory (Oxford University Press 2015, but originally published in 1966

⇲ Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Secrets of the Old Masters by David Hockney (Avery Publishing, 2006)

⇲ In The Blink Of An Eye: How Vision Sparked The Big Bang Of Evolution Andrew Parker (Basic Books, 2004)

As well as many dozens of academic papers from researchers all over the world.

Illustrative material for this excerpt is not necessarily included in the book

Also Featured On