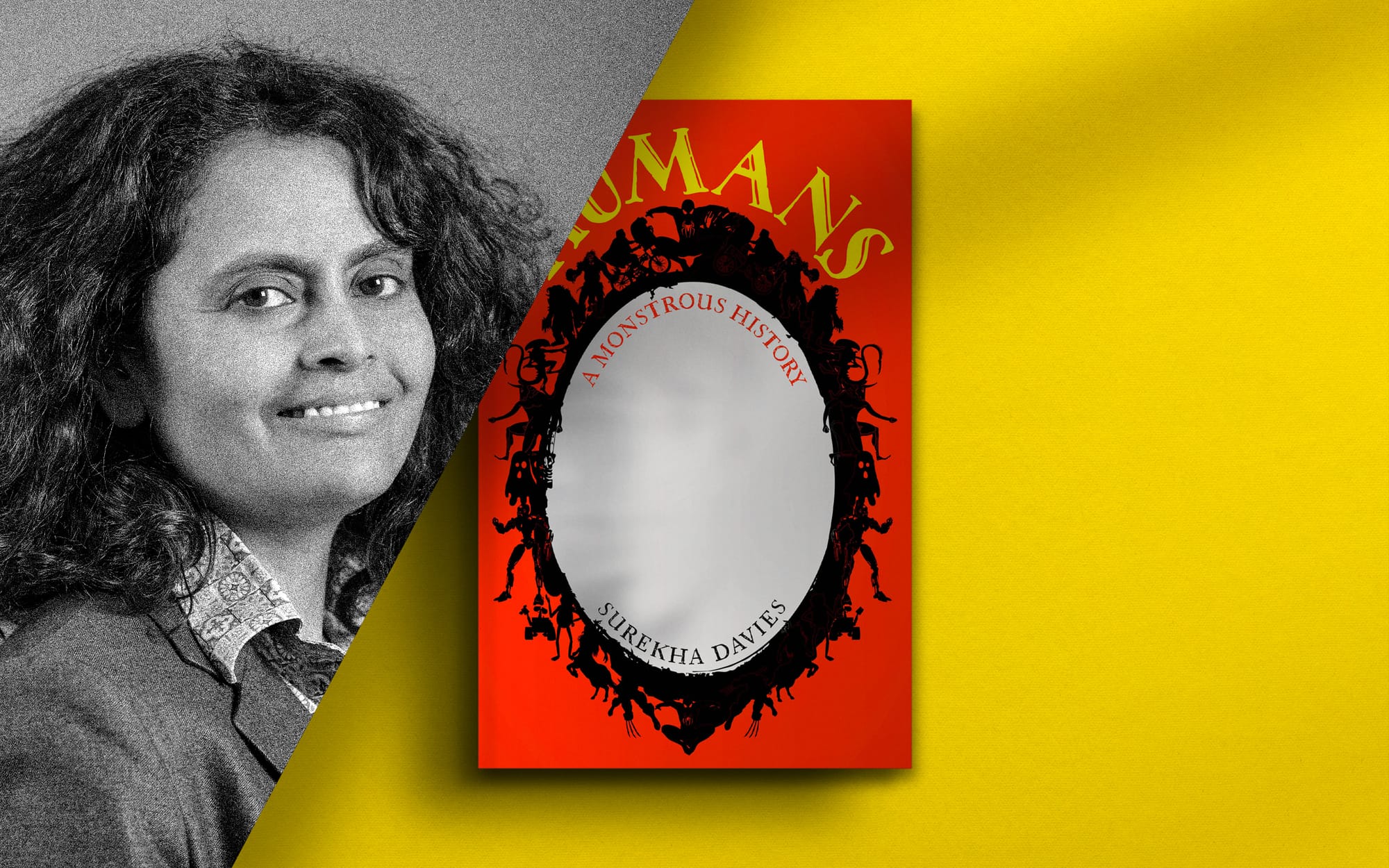

How to Make a Monster with Surekha Davies

Surekha Davies's new book sweeps back through human history in a quest to find the monsters and tell us what they mean

From werewolves to witches, 'monsters' have long been a subject of intrigue and speculation within human societies. They both attract and repel. But what exactly are they? How are they created? What does their presence tell us about ourselves?

Surekha Davies kept questions like these in mind as she cast her eyes back through history, from the Epic of Gilgamesh of the ancient past through to the AI algorithms of today.

In the resulting book, Humans: A Monstrous History, Davies frames her findings. In this interview she explains the origin of this project and tells us why it has a particular resonance today.

Unseen Histories

Can you tell us a little about your academic career and how these experiences have led you to write Humans: A Monstrous History?

Surekha Davies

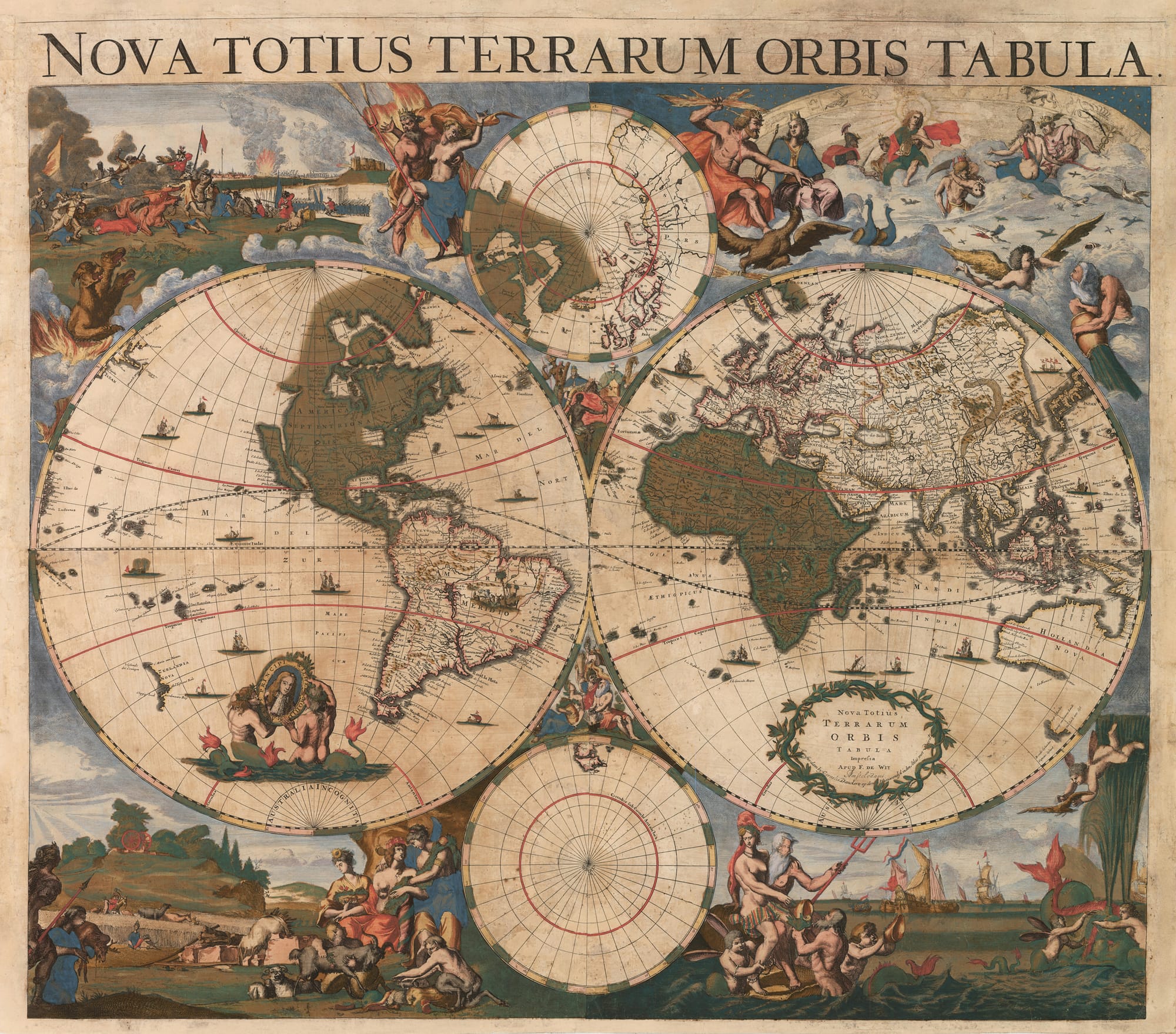

I trained as a historian of science with a passion for understanding the age of European exploration – the centuries around 1492 – shaped by a youth spent watching Star Trek. I wrote my PhD dissertation on images and descriptions of the peoples of the Americas on Renaissance maps.

Here I showed how European mapmakers analysed and synthesised travel and geographical writing about the Americas. They interpreted the region’s inhabitants through ancient geographies that hypothesised that 'monstrous peoples' inhabited distant places. These mapmakers re-configured how Europeans understood the category of the human. This research became the subject of my first book.

While I was writing that, during a fellowship at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC in 2014, I happened to attend an astrobiology conference in the library. Astrobiology is the study of the origins and early evolution of life on earth and the possibility of life on other planets and galaxies.

The conference was called 'Preparing for Discovery: A Rational Approach to the Impact of Finding Microbial, Complex or Intelligent Life Beyond Earth.'

One session explored alien pathogens and weapons, and what, if anything, humanity could do about them. How might societies react and continue in the aftermath of catastrophic first contact? The panellists talked about weapons and defence. But it seemed to me that there were other approaches that no one was talking about.

During the Q&A session, I asked: if we can’t even get along with one another on earth, what chance is there of people behaving calmly if aliens land, or if a deadly alien pathogen takes hold? Shouldn’t we be addressing humanity’s penchant for violence and intolerance if we are to have any chance of surviving learning that we’re not alone in the universe?

But the session chair said that this was the wrong question, and dismissed my observation. And that’s when I realised that I had insights to offer on science and public policy that came not from science or economics but from deep within the cultural study of the premodern past.

Unseen Histories

‘There are no monsters’, your write in the introduction, ‘but all of them are real’. This is playful paradox. Can you explain it for us please?

Surekha Davies

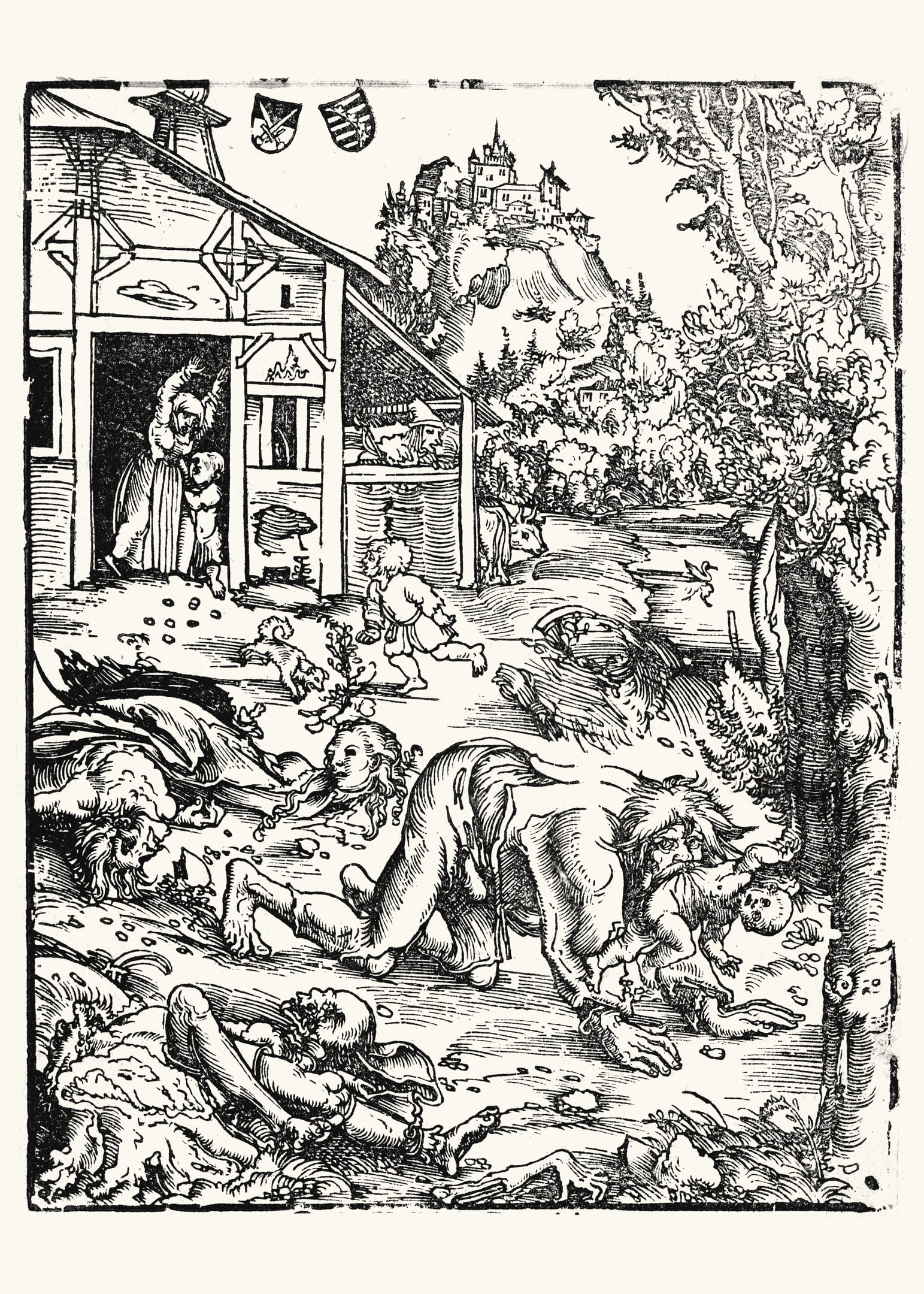

'Monster' is a story, a label to mean 'this thing doesn’t fit neatly in my classificatory system.' A werewolf is a monster because it transcends the categories of human and wolf. But in a different classificatory system, where werewolves were normal, they wouldn’t be monsters.

Monsters are defined and invented in observers’ minds – someone defines a person or thing as monstrous, i.e. beyond the spectrum of 'normal' for categories in their worldview. Monstrosity isn’t innate in anything; it’s a value judgment.

Unseen Histories

Your book confronts a great sweep of time. Can you tell us about some of the earliest monsters you have discovered in recorded history and what their stories suggest?

Surekha Davies

Many of the earliest monsters appear in creation myths. One definition of creation is monster-making: creating something that didn’t exist before.

The ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest monster example I know of, and is possibly the oldest piece of extended literature still surviving. The earliest versions date from around the late second millennium BCE. This epic plays around with the boundary between god and human, and human and animal. The story’s arc suggests not only that these boundaries are porous, but that there’s something for 'civilised' society to learn from the lifestyles of 'wild' beings who are closer to nature.

Today, at a time when industrial agriculture and digital technologies have altered human bodies (pesticides) and minds (attention spans) we should remember that each tool has its place. The wrong hack in the wrong place is no hack at all.

Unseen Histories

There seems to be a recurring theme throughout the book about essence. Some people believed that monsters were created at birth, others that they were shaped through life experiences. Can you say a little about this?

Surekha Davies

Certainly. In Europe between classical antiquity and about the nineteenth century, there were various explanations for one-off monsters. One was about monsters created before birth. These could be nature’s errors as it tried to shape matter, or nature’s jokes.

Another explanation that physicians and naturalists offered was that monstrous births were the consequence of a mother’s imagination. If a pregnant woman saw an extraordinary sight – like a painting of a monkey – or had a fright – as did the mother-in-law of Samuel Pepys’s manservant, who apparently saw a lobster at Leadenhall Market in London – or developed a passion for an extraordinary image, this could affect her unborn child.

Even fantasising about someone other than her husband was something that could supposedly shape a woman’s child at the moment of conception.

But there were also monstrifying processes after birth. People thought of the body as containing four humors or essential substances: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. These humors were affected by the environment, including foodstuffs and temperature. In theory European colonists who moved to regions with harsh climates could become alarmingly different from living elsewhere.

People also understood faith and lifestyle to influence humors. Christian priests in overseas territories worried about European colonists and Indigenous converts to Christianity eating, or continuing to eat, Indigenous foodstuffs or practising 'idolatrous' rites. As the number of mixed-heritage members of the population grew, separating people who were transgressing norms from those who were not became increasingly difficult.

Uncertainties around identifying monsters and their causes made it impossible to draw a firm line separating monsters from 'normal' humans.

Unseen Histories

The years immediately after Columbus’s voyage in 1492 seem a particularly rich time for monster making as the world opened up to Europeans. Is this so?

Surekha Davies

There was so much monster-making! Columbus’s first voyage west was also a voyage south: towards a place thought to engender monsters. And once the first ships sailing under European flags had circumnavigated the globe, a few decades later, that did beg the question: where was the boundary between the human space and monster space?

'Are they fully human?' That debate recurs in colonial sources. In settings where missionaries’ efforts to convert peoples to Christianity met with limited success, some critics argued that it was because Indigenous peoples weren’t fully capable of understanding Christianity.

One theory that reduced the worry that Europeans would also become 'barbarous' was the idea that an unchangeable essence in them limited how much Europeans would change. The nastier side of that thinking was that European thinkers also decided that Africans were more suited for hard labour in the Caribbean.

Colonial laws defined 'black African slave' and 'white Christian servant' as different legal categories – and defined enslaved Africans as property.

Unseen Histories

And yet you write about Antonietta Gonsalvus who was born in Paris in the 1580s. Can you tell us a little about her and how people made sense of her story?

Surekha Davies

Antoinette Gonsalvus’s face was covered in hair, a condition she had inherited from her father, Petrus Gonsalvus. As a child, Petrus had been kidnapped in the Canary Islands by Spanish sailors, and taken to the French royal court. He grew up there, became a courtier, and married a Frenchwoman, with whom he had six children who survived infancy.

Antoinette, like the rest of the hairy members of her family, was treated a bit like a pet, a trophy, a scientific specimen, or an enslaved person. Artists and naturalists like Ulisse Aldrovandi and Joris Hoefnagel included illustrations of Antoinette in albums with animals.

Aldrovandi examined Antoinette, and wrote that the hair on her forehead was roughest and longest, the hair on her cheeks the softest – softer than the hair anywhere else on her body – and that she was 'bristling with yellow hair up to the beginning of her loins.' Antoinette’s privacy and dignity were stripped from her because of a single unusual physical characteristic.

People who observed Antoinette responded to her hairiness by comparing her to animals. Her life, despite its courtly comforts and beautiful outfits, was one in which she was framed as something that blended the categories of human and animal.

Unseen Histories

When people think of monsters in early modern literature, one of the most prominent of them is Shakespeare’s Caliban. He is a character who features in your book. Can you tell us what you believe his significance to be?

Surekha Davies

In The Tempest, Caliban’s humanity is contested by people around him: they describe him as having every monstrous attribute imaginable.

The sorcerer Prospero, marooned on Caliban’s island, calls Caliban a creature born of a union between a witch who worshipped a false god and the devil. Caliban was, to Prospero, 'not honoured with human shape,' a 'poisonous slave,', a 'moon-calf' born under the influence of the moon, which was believed to deform minds and bodies. Caliban’s speech was apparently mere babble until Prospero’s daughter Miranda had taught him to speak properly.

Caliban’s significance is twofold. First, he’s a metaphor for ongoing colonial dispossession and Indigenous slavery (The Tempest was first performed in 1611). Prospero had enslaved Caliban, dispossessing him of the island that Caliban considered to be his birthright.

Second, despite how different he appears to everyone else, the boundary between Caliban and polite society and humanity was porous. Prospero fears for Miranda, with whom Caliban might spawn a tribe of monsters. Indeed, Caliban boasts that he might have 'peopled …. This isle with Calibans.'

Unseen Histories

An intriguing source you mention is a ‘monster scrapbook’ compiled by a manservant to Samuel Pepys and titled: A Short History of Human Prodigious and Monstrous Births. Was this a project rich in such archival discoveries?

Surekha Davies

The history of ideas about monsters has been a vibrant field in the humanities for some time. The sheer quantity of source materials – books, manuscripts, newspaper cuttings, fairground advertisements, and unpublished archives of scientific societies – means there are numerous questions still to ask.

Manuscripts like James Paris du Plessis’s monster scrapbook are so rich that there is much more to say about it. Many materials are noted in library and archival catalogues and appear in the bibliographies of published work.

But each book is only long enough to scratch the surface of the sources and the questions that we could ask of them. So yes, I realised that there’s enough material here for many more books!

Unseen Histories

You use the sonorous but sinister word ‘monstrifying’ to describe what happens to people who don’t fit with society’s expectations. One of the most striking examples of this comes between the fifteenth and eighteenth century: the witch hunts. Have you gained a new perspective on this period through your work on this book?

Surekha Davies

I’ve learned the power of stories to frame people as human beings just like us or as monstrous threats. During the witch hunts state authorities wanting to centralise power tapped into people’s everyday fears – crop failures, sickness, death – and enabled emerging stories about malevolent witchcraft, supposedly performed mainly by women, that were increasingly interpreted as the causes of such misfortunes. Women were particularly easy to monstrify since they already suffered from being framed as inferior.

Law courts tried and sentenced people for the alleged crime of witchcraft. Thousands were tortured and executed. Stories about how, say, your neighbour’s 'evil eye' must have caused your cow to die led to sustained witch hunts and tragedy because authorities became complicit in monster storyboarding.

Unseen Histories

Your book runs right up the present day, when we humans are starting to grapple with the challenges of AI and the appearance of robots. What lessons from history would you like us to bear in mind as we confront such things?

Surekha Davies

Humans have a long history of choosing to monstrify one another. The first lesson is to recognize this for what it is: to notice, for example, how people invaded the privacy of individuals like Antoinette Gonsalvus, or the fates of people labelled as 'degenerate' threats to the nation who perished in Nazi death camps. Do not fall for monstrifying narratives.

Second, look for the hidden agendas of people pushing these narratives, stories that often tap into older patterns of dehumanization.

I’m reminded of the firebrand Scottish Protestant preacher John Knox, who was furious that Mary I, a Catholic, became the reigning Queen of England. Knox wrote a pamphlet, The Monstrous Regiment of Women, in which he used words like 'monster' and 'monstrous' to characterize the idea of a woman as a leader. He wanted nobles to rise up against her rule – to make it possible for them to commit what might otherwise have been branded as treason – and he appealed to their misogyny in an attempt to achieve his goal.

And third, remember that monster-making is contagious: the wide array of people who were treated as little more than curiosities for gawking at in fairgrounds, shows how anyone can be monstrified and then lose rights to privacy, dignity, and bodily autonomy.

AI boosters in the present age of tech oligarchs are using the same playbook of dehumanisation, but with one difference: almost no one will be left who counts as a person whose rights will not be trampled.

And if we outsource those activities that are the essence of being human – like creative and communicative acts that represent what our minds, perspectives, feelings, education, and experience can uniquely create, and that transform us through the effort it takes – will we still be human? 𖡹

Davies has a BA and an M.Phil. in history and philosophy of science from the University of Cambridge and a Ph.D. from the University of London. She is the author of the multi-award-winning Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters.

After working as a curator and as a history professor, Davies became a full-time author and speaker. Her new book is Humans: A Monstrous History.

Humans: A Monstrous History

University of California Press, 4 March, 2025

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-0520388093

A history of how humans have created monsters out of one another—from our deepest fears—and what these monsters tell us about humanity's present and future.

Monsters are central to how we think about the human condition. Join award-winning historian of science Dr. Surekha Davies as she reveals how people have defined the human in relation to everything from apes to zombies, and how they invented race, gender, and nations along the way. With rich, evocative storytelling that braids together ancient gods and generative AI, Frankenstein's monster and E.T., Humans:

A Monstrous History shows how monster-making is about control: it defines who gets to count as normal. In an age when corporations increasingly see people as obstacles to profits, this book traces the long, volatile history of monster-making and charts a better path for the future. The result is a profound, effervescent, empowering retelling of the history of the world for anyone who wants to reverse rising inequality and polarization. This is not a history of monsters, but a history through monsters.

"Humans documents the curious ways we have thought about who counts as human throughout history, from Pliny's belief that extreme environments created monstrous people to the 18th-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus's four subtypes of humans. Most significant for our time, however, are Davies' thoughts on nation states - the way ideas about race and birthrights are used for dark political ends - and on how AI might end up monstering us"

– New Statesman

"Davies's book is a radical and timely plea to renew our focus on the humanities. At a time when biology and other sciences are making great strides in understanding how we are put together, chemically and physically, Humans makes clear how vital it is that we invest in understanding how we are put together culturally"

– Chronicle of Higher Education

With thanks to Sophie Portas