In Pursuit of Margaret Paston

For twenty five years Diane Watt has been searching letters and landscapes for traces of one of the fifteenth-century's most intriguing figures

For historians of the tumultuous fifteenth century, a time best remembered for the Wars of the Roses, the Paston Letters are a vital primary source.

Written by members of the Paston family of Norfolk, the letters describe day-to-day life in that distant time.

Two decades ago the scholar Diane Watt produced a new selection of the Paston Letters, focussing on those written by women. Out of this project grew a second. This was a full biographical study of one of the central figures in the archive: Margaret Paston.

Twenty-five years ago, I visited the British Library in St Pancras to look at the bound volumes of the original Paston correspondence, a collection relating to a wealthy family in fifteenth century Norfolk.

I had known about the collection for years: it is a vitally important source for historians working on the chaotic decades of the Wars of the Roses and I was excited to see the original documents.

These were letters that were composed, often in haste, locked and sealed, and entrusted to a messenger to deliver. They were written in dangerous times, and some included the instruction, evidently ignored, that they should be destroyed once they have been read.

My motivation for examining the manuscripts was not primarily to explore their political significance. I was there because I had been invited to edit the letters written by the women of the family. I was particularly interested in the correspondence of Margaret Paston, the most prolific writer in the family.

Margaret was from a very affluent family and after her father died, when she was still a child, she inherited his extensive estates. She was therefore a desirable match for the Pastons, whose own wealth had been only recently won. The marriage was an arranged one, and it was successful. The couple soon became deeply fond of one another.

Margaret’s husband, John, had studied at Cambridge and, when the couple married, he had recently qualified as a lawyer. Throughout the marriage, he was forced to spend a lot of time working away from home at the Inns of Court in London and elsewhere.

Margaret therefore relied on their exchange of letters as a means of maintaining contact during these prolonged absences. After her husband’s premature death, she mainly wrote to her two eldest sons, who both, in succession, took over as head of the family.

Margaret’s letters are incredibly wide-ranging: she writes about domestic matters, family crises, and political intrigues. She sends her husband and sons requests for provisions, clothing, medicines and weapons, gives first-hand accounts of sieges and battles, and provides legal and political advice as well as news updates and occasional snippets of gossip.

My sense of Margaret is that she was an intelligent, forceful, and forthright figure, tremendously loyal to her husband, a woman who cared deeply about her friends as well as her family. Even after I published my anthology of the Paston women’s letters, I wanted to find out more and it was this curiosity that led me to begin to write her biography.

With this aim in mind, I decided to travel to East Anglia, to find out what, if anything, the places where she lived or visited could add to my understanding of her life.

A few years ago, I took my first trip, accompanied by my wife and our three dogs, and armed with a copy of Nikolaus Pevsner’s guide to Northeast Norfolk and Norwich.

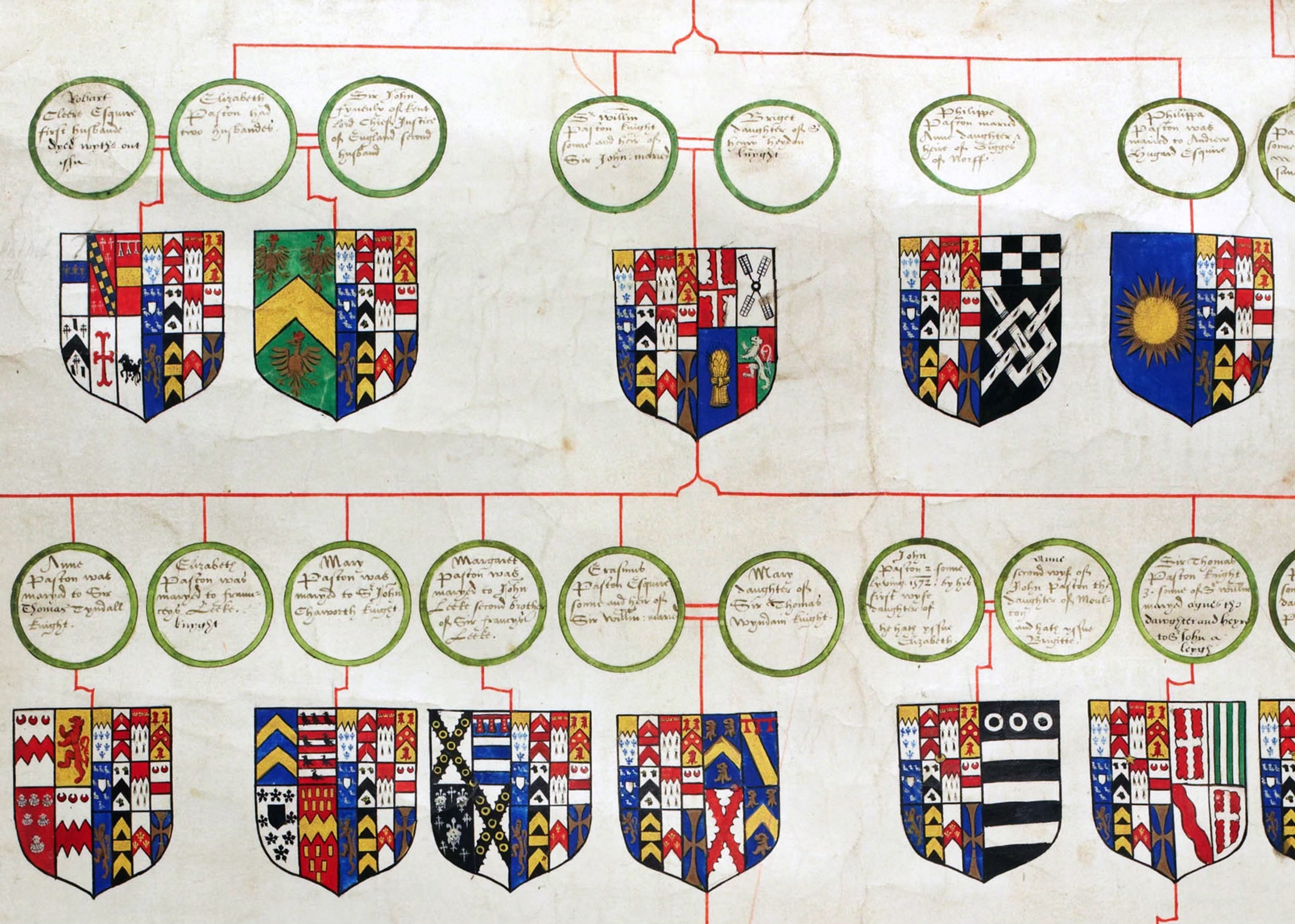

We started with Paston, the village from whence Margaret’s marital family took its name. Little or nothing of the medieval manor house is preserved in the present-day hall, but the Church of St Margaret in Paston, where the family worshipped, has a wooden pew end adorned with their heraldic griffon, as well as some medieval wall paintings and tombs.

From Paston, we travelled on to nearby Bacton, now dominated by an enormous gas terminal, the site of Bromholm Priory, where Margaret’s husband was buried with great pomp and at tremendous expense. The ruins are visible in the fields, a pillbox, part of the coastal defences of World War II, half hidden in the remains of the central tower.

At both Paston and Bacton, I had a strong sense of these locations as palimpsests, where the medieval past has been partially erased and overlaid by subsequent building work and modern developments.

Nevertheless, sufficient traces remain for me to picture Margaret kneeling in worship in the nave of the church or to see in my mind’s eye John’s funeral cortege passing through the abbey gates.

That first visit to Norfolk was to be only the first of many journeys to the sites and locales of Margaret’s letters.

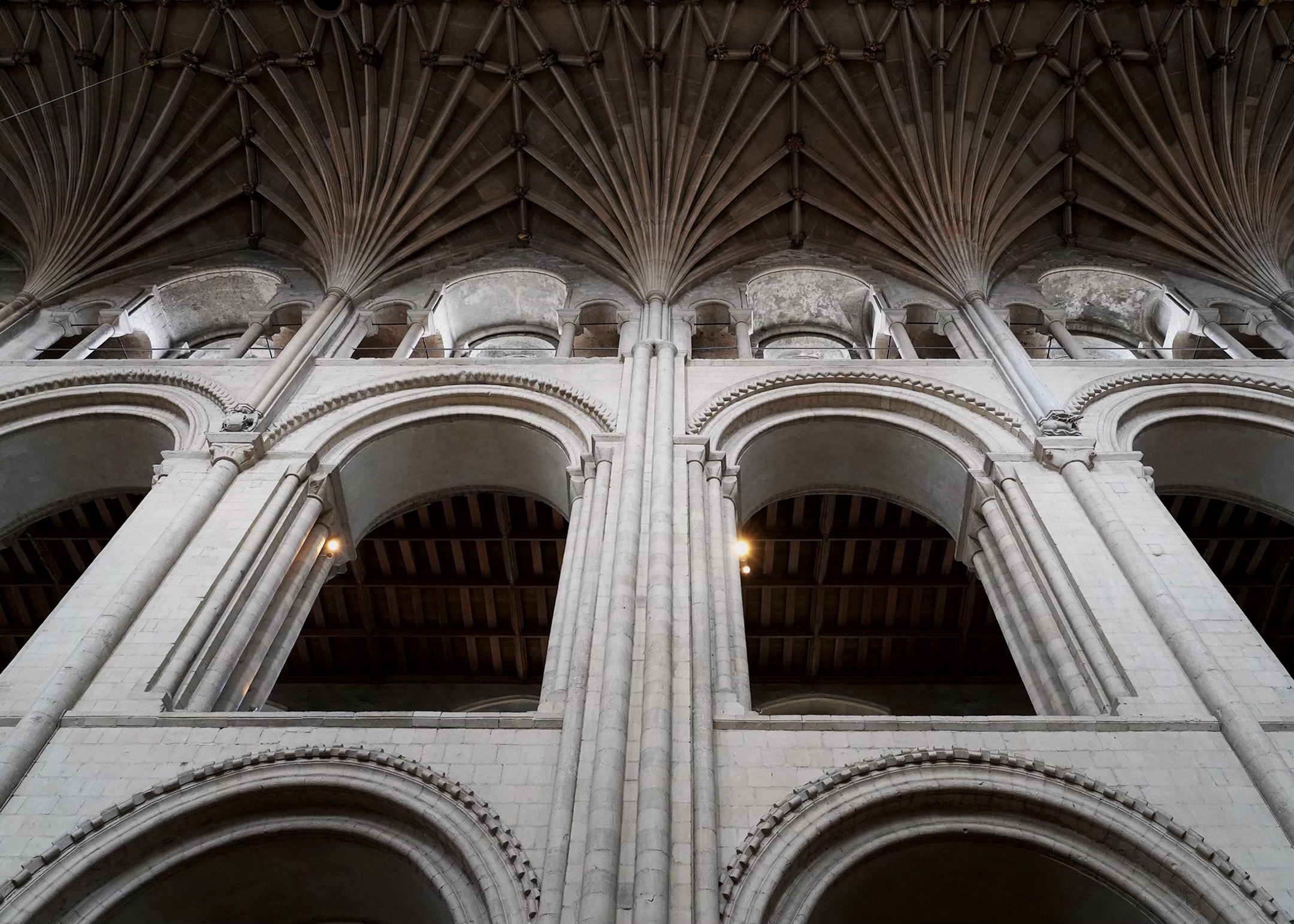

Over the ensuing years, I have often found myself wandering through Norwich, from the Cathedral and its precinct, along beautiful Elm Hill, the historic street where the family settled, past their former parish church of St Peter Hungate, and across to the present-day Halls, once part of the medieval friary.

Of course, many of the buildings have been lost or modified. St Peter Hungate, for example, was deconsecrated in the 1930s but the structure was preserved as a museum and, fittingly enough, it is now an exhibition space dedicated to Norwich’s medieval past.

The church was dear to Margaret and her husband—they paid for its restoration, and Margaret’s favourite son, Walter, was subsequently buried there. A student in Oxford, he fell ill of the pestilence and was brought home to his mother before he passed away.

In my travels, I found myself trudging deep into the Norfolk countryside. I sought out the site of Margaret and John’s first home in Gresham, which, in its heyday, had been a large fortified and moated complex, complete with a drawbridge. The living quarters, in the form of a manor house, were located within the battlemented walls.

When, early in her marriage, Paston's enemies laid claim to the property, Margaret did her best to lead its defence, but eventually she was forced to flee from their attack.

The buildings were destroyed, and today the isolated ruins are almost indiscernible, situated in farmland and hidden by trees and vegetation, a powerful reminder of the loss that Margaret and her husband experienced.

As I researched Margaret’s later years, I found myself in the peaceful village of Mautby, near Great Yarmouth. Margaret eventually retired there.

I was lucky enough to be welcomed into Hall Farm House by the current owners and allowed to explore the grounds in search of traces of Margaret’s home and the chapel she had built there for her private devotions, and that became increasingly important to her as her health began to fail.

After her death, Margaret’s body was interred in the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Mautby, but no traces of Margaret’s tomb remain.

The side aisle in which it was located fell into decay and was demolished long ago, although on a hot dry summer day the aisle’s outline can be detected in the scorched grass and a plaque now marks the approximate location of her grave.

While Margaret’s correspondence makes frequent reference to the political and social upheaval of her time, she did not write about the Norfolk landscape or the natural world.

Nevertheless, even though, or perhaps because, many of these sites have been ruined or fallen into disrepair over the centuries, retracing the places that mattered to Margaret and walking the streets and country roads that would have been so familiar to her has brought her letters to life, enriching my understanding of the events and experiences she describes •

This feature was originally published August 15, 2024.

God's Own Gentlewoman: The Life of Margaret Paston

Icon Books, 28 August, 2025

RRP: £10.99 | ISBN: 978-1837731657

“With nuance, deep leaning and insight… bringing the medieval world into shimmering view” – Helen Castor

The remarkable story of Margaret Paston, whose letters form the most extensive collection of personal writings by a medieval English woman.

Drawing on the largest archive of medieval correspondence relating to a single family in the UK, God's Own Gentlewoman explores what everyday life was like during the turbulent decades at the height of the Wars of the Roses. Covering topics including political conflicts and familial in-fighting, forbidden love affairs and clandestine marriages, bloody battles and sieges, fear of plague and sudden death, friendships and animosity, and childbirth and child mortality, Margaret's letters provide us with unparalleled insight into all aspects of life in late medieval England.

Diane Watt, a world expert on medieval women's writing, offers insight into Margaret's activities, experiences, emotions and relationships, presenting the life of a medieval woman who was at times absorbed by the mundane and domestic, but who found herself caught up in the most extraordinary situations and events.

With thanks to Elle-Jay Christodoulou.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store