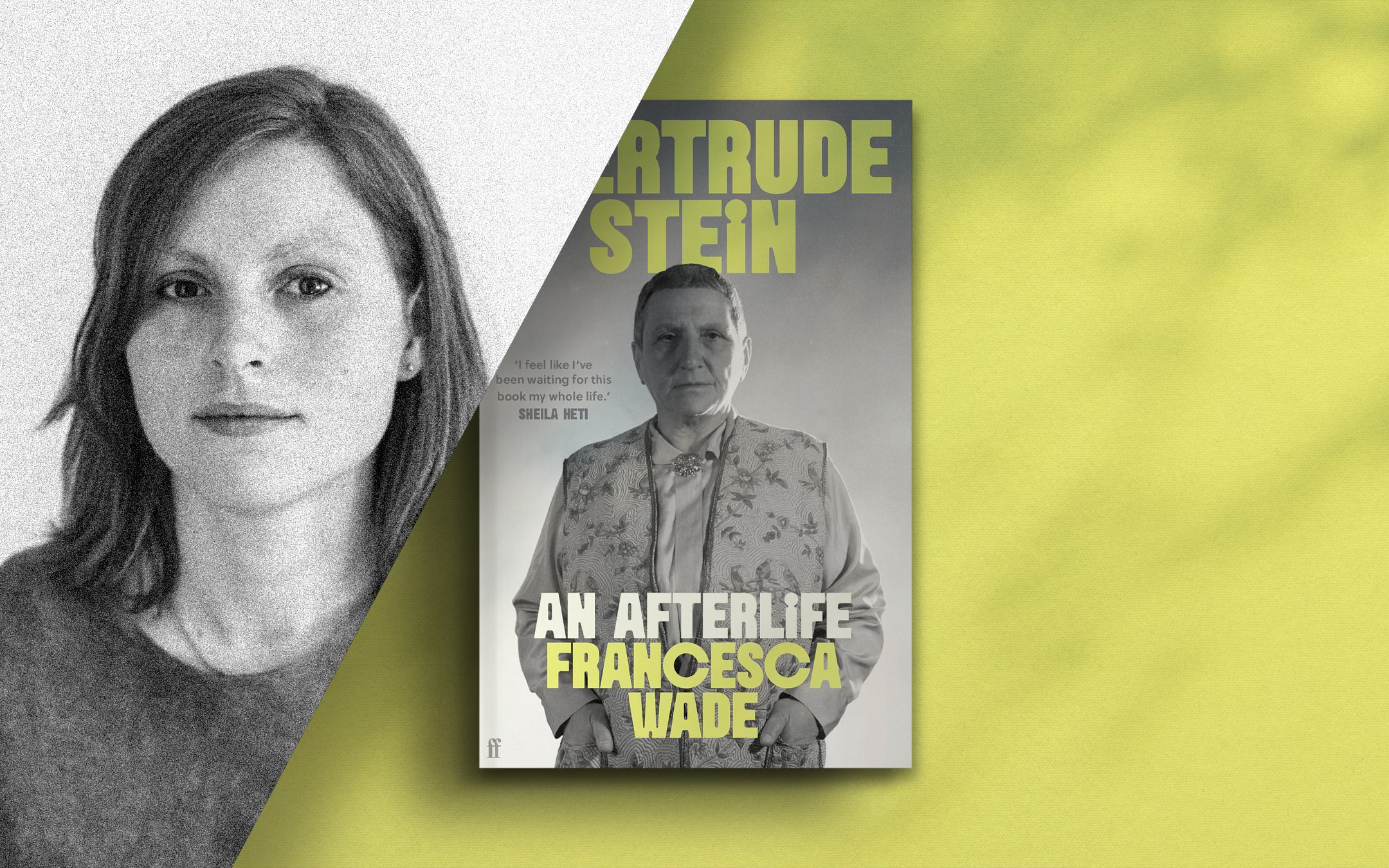

In Search of Gertrude Stein with Francesca Wade

Francesca Wade tells us all about her new book, Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife

Gertrude Stein was a writer, art collector, avant-gardist and a free-thinker. Today her significance as a twentieth-century cultural figure is acknowledged by all, but there remains something mercurial about her character.

For the past few years Francesca Wade has been researching Stein's life. In her new book, Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife, she reflects on her creative output and considers her intensions.

Questions by Hannah Wuensche

Unseen Histories

How was Gertrude Stein an influential figure, and what associations do people tend to make with Stein today?

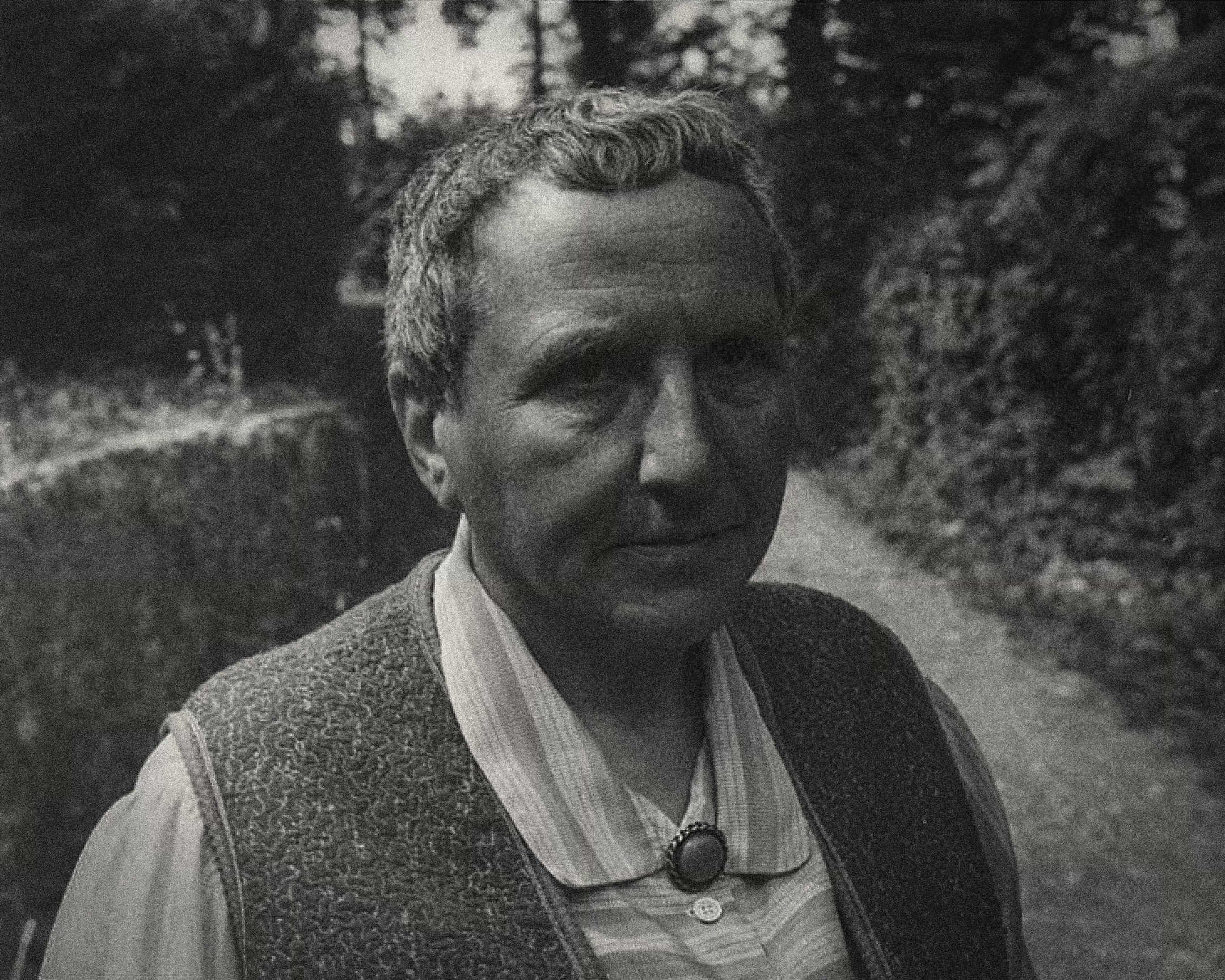

Francesca Wade

In the course of writing this book, I’ve had reason to mention Stein to many, many people: I’d say most recognise her name, but few know much about her.

It’s a conundrum that has always characterised Stein’s reputation: she quickly became famous as a personality, while her writing – which is what she really wanted to be remembered for – remained little read.

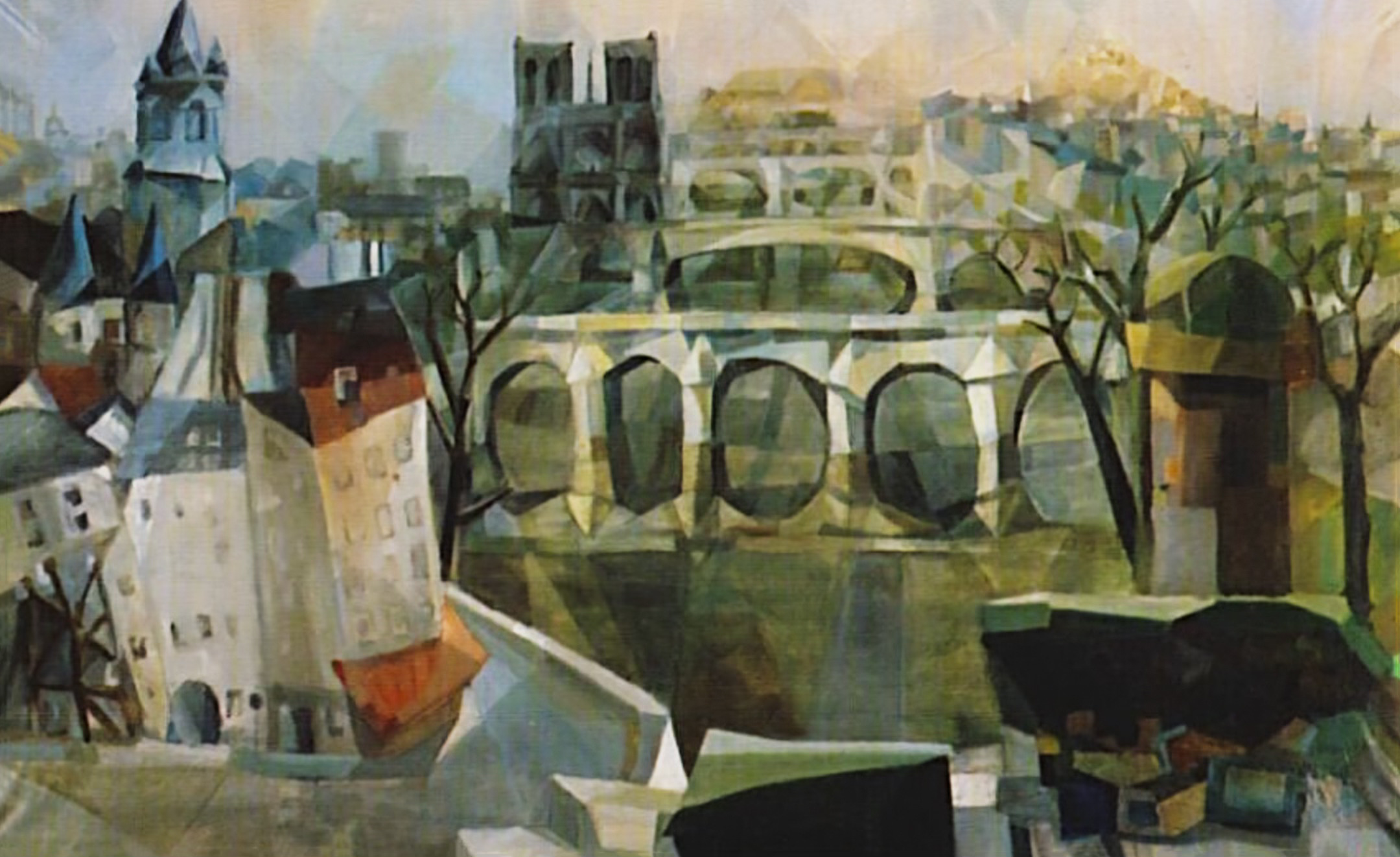

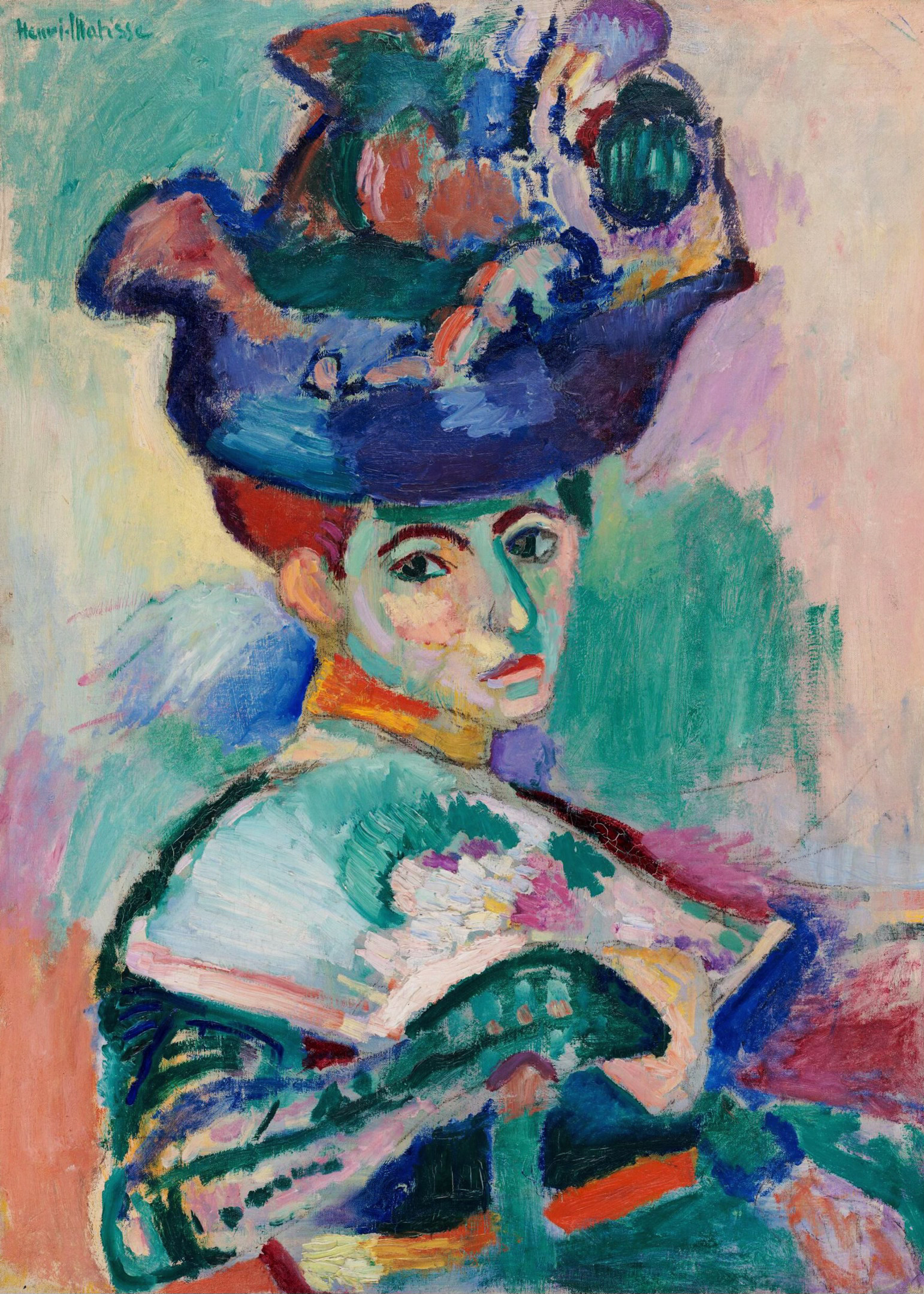

She’s often remembered as a collector of art, one of the first to buy works by the likes of Matisse and Picasso (who painted her portrait), or as the host of Saturday night salons at her home in Paris, where visitors thronged to see her paintings (the apartment she shared with her brother, at 27 rue de Fleurus, was practically the first museum of modern art).

More recently, she’s been celebrated as a queer icon, a lesbian writer whose work brims with eroticism. But her avant-garde writing – which has been enormously important to many poets, novelists, artists, dancers and theatre-makers – is central to my account of her life, and to her enduring influence.

Unseen Histories

As you say, Stein prioritised her identity as a writer above all else: you write that she expressed a wish that paintings from her collection be sold to fund the publication of her manuscripts after her death. How did she feel about the recognition (or lack thereof) that she received as a writer in contrast to her reputation for her other pursuits?

Francesca Wade

Deeply frustrated! 'It always did bother me that the American public were more interested in me than in my work,' Stein wrote in 1936, after a seven-month tour of the US designed to draw in doubting readers, who’d been won over by her charming, gossipy bestseller The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, but baulked at her 'real' writing, which was widely derided as difficult, unreadable, nonsense.

Stein always insisted her work was for everyone: she was bemused to be lionised as a celebrity while her manuscripts languished unread, consistently rejected by publishers hungry for another juicy memoir. But she believed her innovations would be recognised eventually – that truly radical work won’t necessarily be appreciated in its own time.

In the last decade or so of her life, I think she set her sights on posthumous recognition – building an archive, and tasking friends with ensuring her work would be published after her death, trusting that future readers would find it.

Unseen Histories

You have written before in Square Haunting about women writers in Bloomsbury (where Stein briefly lived) who were exploring a model for female independence around the same time. Stein, though, seems to have distanced herself from the feminist movement. How much did gender play a role in Stein’s image of herself?

Francesca Wade

Stein’s relationship with gender is complex and fascinating: she briefly (and ambivalently) participated in feminist activism as a young woman in America, but tended to avoid organised movements, and rarely spoke about feminism or gender directly.

In her twenties she read deeply into the work of the characterologist Otto Weininger, who argued that only those with ‘masculine’ traits could aspire to genius. She played with a masculine image – cropping her hair, taking up space, wearing androgynous corduroy gowns – which, I think, was designed both to highlight her claim to intellectual freedom, and to subvert the idea that the advantages associated with masculinity need be confined to men.

Unseen Histories

Stein took very intentional steps towards establishing her literary legacy, notably depositing an enormous amount of material with the Yale archive, which you were able to consult. Could you tell us about the material you found there and any insights these gave you that you couldn’t get from Stein’s published work?

Francesca Wade

Stein’s writing always took its cue from her surroundings and present state of mind, and her manuscript notebooks reveal a trove of insights into her process of composition. In their handwritten drafts, her texts – which often seem abstract in printed form – mingle with shopping lists, menus, snippets of overheard conversation, and intimate notes to her partner, Alice B. Toklas.

Reading the manuscripts is a totally different experience to reading Stein’s published work, and reveals so much about the conditions of its creation, and the ‘struggle’ – as Stein put it – of doing what she set out to achieve in her texts: conveying perception in language.

The archive is also full of surprising documents which shed further light on aspects of Stein’s life she didn’t write about directly in her autobiographies, from a forgotten novel depicting a fraught love triangle to early notebooks in which she recorded her impressions – often extremely scathing! – of everyone in her orbit.

Unseen Histories

A significant part of Stein’s legend is her relationship with her life-partner Alice B. Toklas, in whose voice Stein writes in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. As you write, 'it’s impossible now to imagine either one without the other'. In what ways was this relationship important to Stein’s work and image during her life, both publicly and privately?

Francesca Wade

Her relationship with Toklas formed the context to everything Stein did. Her support – both practical and emotional – was crucial to Stein’s ability to write.

From the outside, it often looked as though their relationship conformed to heterosexual stereotypes (Stein cheerfully dominant, Toklas almost comically subservient): at their parties, Stein held court while Toklas remained silent, steering unwelcome guests away from Stein. Friends muttered darkly about Toklas’s coldness; after Stein’s death, some realised they had never heard her speak.

But the private materials held in their shared archive deepen this picture immeasurably, revealing a complex, intimate, teasing dynamic, each thriving in the other’s presence.

Unseen Histories

Your book describes how Toklas became central to the posthumous formation of Stein’s legacy. After Stein’s death, she was interviewed by Leon Katz, but until 2017 these notes were locked away. As the first researcher to see Katz’s notes, what did you learn about Toklas’s perspective, which was so often overshadowed by that of her partner?

Francesca Wade

After Stein’s death, Toklas (who lived on, alone, for a further twenty years) was reluctant to speak to biographers – she insisted that everything they needed to know about Stein’s work could be found in her archive at Yale University.

But Leon Katz, a young researcher from Columbia University, found some material there which piqued Toklas’s interest: a trove of notebooks in which Stein had written copiously during her first decade in Paris, the period in which she discovered modern art, began writing, and met Toklas.

Katz’s interviews mark the first time Toklas really spoke openly about her life with Stein: I found her comments a deeply moving insight into the origins of their relationship and her total commitment to Stein’s project.

Unseen Histories

Two other names are prominent in your narrative of Stein’s posthumous legacy: Donald Gallup, the curator who worked on Stein’s papers, and Carl Van Vechten, Stein’s friend whom she named as her literary executor. Could you talk about the dynamic between Toklas, Gallup and Van Vechten?

Francesca Wade

Over the last decade of her life, Stein sent regular batches of material to the Yale University Library – notebooks, drafts, letters, personal effects – which formed, at her death, one of the archive’s largest collections.

In her will, she appointed her friend Carl Van Vechten as her literary executor, charged with seeing to publication all the manuscripts Yale held. Across the next decade, Gallup and Van Vechten worked closely together, alongside (and sometimes at odds with) Toklas, to cement Stein’s legacy.

They soon discovered that carrying out their duties to Stein would entail navigating complex moral dilemmas relating to Toklas, intruding into – and potentially disrupting painfully – her own memories of their shared past.

The dynamic between these three gatekeepers, each with a different stake in Stein’s legacy, raises fascinating questions about the ethics of biography, and how to negotiate the blurred lines between the life and the work.

Unseen Histories

For many, Stein’s activity during the Second World War casts a dark shadow on her legacy. Could you elaborate on Stein’s relationship with the Vichy government, which at times appears uncomfortable or perhaps contradictory?

Francesca Wade

Stein’s politics were complicated, and not particularly coherent. Like many in France, she supported Pétain’s Armistice in 1940, and even began to translate some of his speeches (these were never published, and she abandoned the project well before the war’s end; the circumstances of its inception remain unclear).

Over the course of the war, witnessing the bravery of Resistance fighters in the countryside where she and Toklas lived, she changed her mind – slowly – about Pétain, and charts her ambivalent feelings in her memoir Wars I Have Seen.

Stein’s long friendship with Bernard Faÿ, who took a high position in the Vichy government and was later prosecuted for his collaborationist activities, has come in for much scrutiny in recent decades: in my book I hope to debunk some of the more inaccurate aspersions that have been cast on Stein, not in any way to whitewash the uncomfortable aspects of her life, but to provide context, and nuance, to all she did and didn’t do during this fraught period.

Unseen Histories

Finally, your book brings out how intensely interested Stein was in what it means to be remembered, or 'to be historical'. What do you think it was about this 'historical' status that so appealed to her, or seemed so important?

Francesca Wade

Stein wanted her work to be read and reckoned with; I think she saw literary futurity as a way of surviving after death and transcending mortality, which had terrified her from a young age.

As she saw her peers be celebrated and canonised while her reputation lurked on the margins of respectability, she wanted – I think – to write into the future, for an audience she couldn’t yet imagine. And I’m glad she did! She anticipated readers like John Cage, like Frank O’Hara, like Lyn Hejinian, who built on her innovations as they forged their own pathbreaking work.

I have loved untangling her self-mythology: she has been brilliant company for the past several years and, above all, I know I’ll never stop reading her work •

This interview was originally published June 30, 2025.

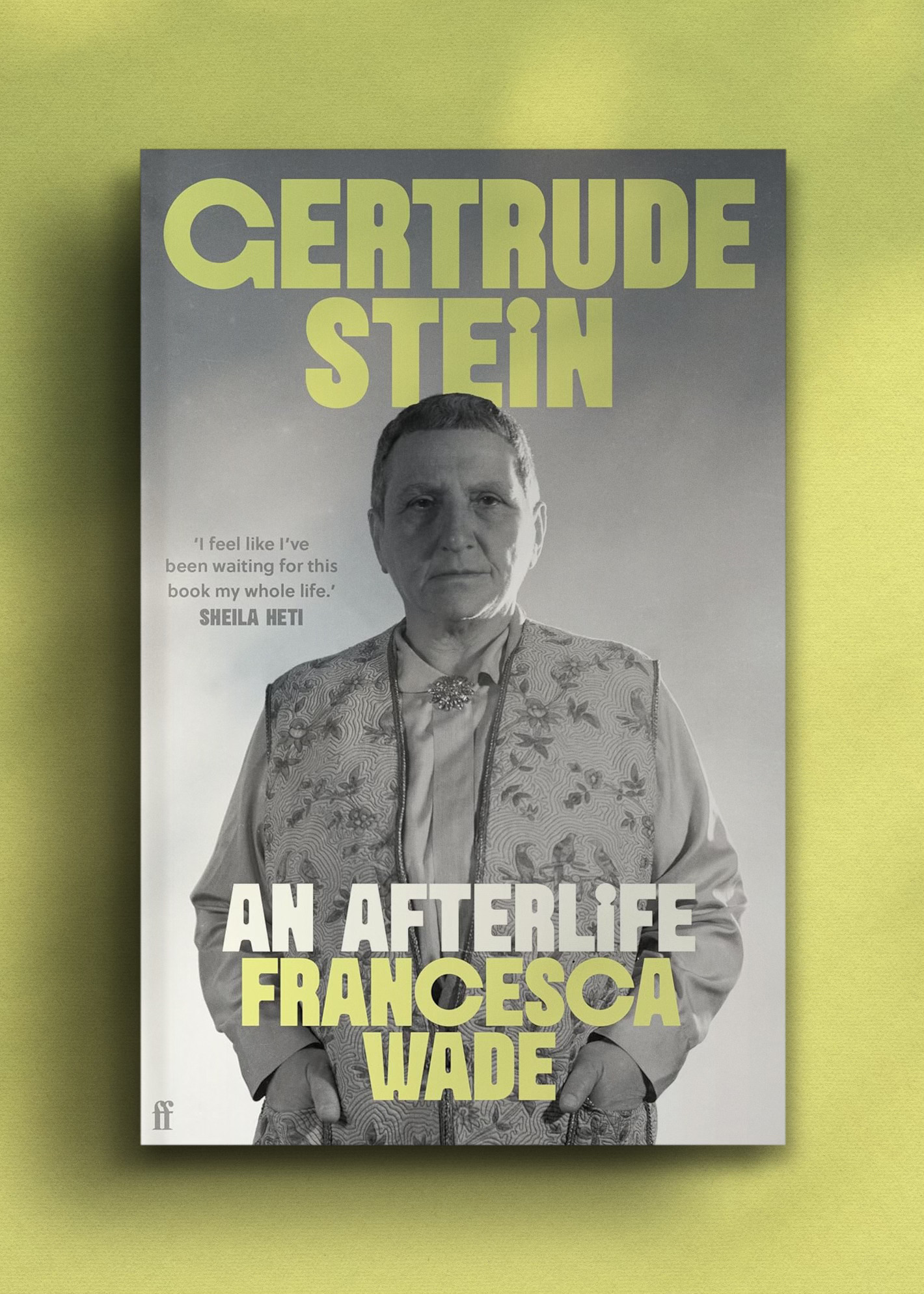

Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife

Faber, 22 May, 2025

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-0571369317

“Strikingly accomplished . . . utterly compelling” – The Sunday Times

‘Think of the Bible and Homer, think of Shakespeare and think of me’ wrote Gertrude Stein in 1936. Admirers called her a genius, sceptics a charlatan: she remains one of the most confounding - and contested - writers of the twentieth century.

In this literary detective story, Francesca Wade delves into the creation of the Stein myth. We see her posing for Picasso's portrait; at the centre of Bohemian Parisian life hosting the likes of Matisse and Hemingway; racing through the French countryside with her enigmatic companion Alice B. Toklas; dazzling American crowds on her sell-out tour for her sensational Autobiography - a veritable celebrity.

Yet Stein hoped to be remembered not for her personality but for her work. From her deathbed, she charged her partner with securing her place in literary history. How would her legend shift once it was Toklas's turn to tell the stories - especially when uncomfortable aspects of their past emerged from the archive? Using astonishing never-before-seen material, Wade uncovers the origins of Stein's radical writing, and reveals new depths to the storied relationship which made it possible.

This is Gertrude Stein as she was when nobody was watching: captivating, complex and human.

“A masterpiece of biography”

– The Sunday Telegraph

“I feel like I've been waiting for this book my whole life”

– Sheila Heti

With thanks to Josh Smith.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store