Entertaining America: the Federal Theatre Project with James Shapiro

The origins of today's Culture Wars can be found in the 1930s, argues James Shapiro

The term 'culture wars' was only popularised in the 1990s, when the sharp divisions between liberal and conservative America were becoming more stark.

But in a new study, The Playbook, the author and literary scholar James Shapiro traces the roots of today's confrontation back to a specific moment in American political history.

In the 1930s Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced a raft of New Deal legislation that was designed to help a bruised nation back onto its feet. Among the various programs was one called the 'Federal Theatre Project'. Filled with utopian ideals, it drew the ire of those who detected something un-American in it. In this interview Shapiro tells us more about a short-lived scheme that left a very long legacy.

Unseen Histories

I should start this with a note of congratulation. Last year your book 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (2005) was chosen as the ‘winner of winners’ in a special 25 anniversary edition of the Baillie Gifford Prize, the UK’s premiere non-fiction award. This is a great accolade and it makes me wonder how you, yourself, look back on that work, several decades on?

James Shapiro

The shelf-life of scholarly books, and non-fiction in general, tends to be short, a lot shorter than for fiction. So I am really pleased, and also surprised, that 1599 is still read and valued.

I’d attribute its success to a number of factors: I was able to spend fifteen years researching and writing it (a luxury afforded to few writers); it was my fourth book, so I had by then found a voice; cradle-to-grave biographies were beginning to feel a bit shopworn, so my approach, recounting just a year in the life, offered a satisfying alternative; and most of all, I was able to build upon the extraordinary advances in Shakespeare studies in the 1980s and 1990s.

Unseen Histories

Shakespeare is obviously the keystone for English literature. Is one of the powerful dynamics behind The Playbook, your newly published book, the fact that there is no such single, unifying figure in the United States of America?

James Shapiro

Shakespeare is obviously the keystone for English literature. Is one of the powerful dynamics behind The Playbook, your newly published book, the fact that there is no such single, unifying figure in the United States of America?

There is no American novelist, poet or playwright—not Melville, Faulkner, Twain, Emily Dickinson, Arthur Miller, or Toni Morrison—who is universally taught or read in the United States.

The thousand or so productions mounted by the Federal Theatre really captured the diversity that America prizes and prefers: from updated classics (including Shakespeare) to vaudeville to musicals to edgy social drama.

Unseen Histories

In The Playbook you write about the long quest to build a national theatre in the USA. By the 1930s this idea had been much mooted and much frustrated. Can you tell us a little about this?

James Shapiro

In The Playbook you write about the long quest to build a national theatre in the USA. By the 1930s this idea had been much mooted and much frustrated. Can you tell us a little about this?

There had been calls for a national theatre for about as long as there has been a United States. What was different about the desire for one in the 1930s is that theatre had been so hollowed out in the previous quarter-century, thanks to the wild success of the movies.

You could argue that America really had something approaching a national theatre in the late nineteenth century—with playhouses in every town across the land and touring companies and stars reaching the hinterlands. But the bottom fell out around 1910, and by the 1930s, with theatres turned into moviehouses and actors and stagehands out of work, voices for subsidizing something on a national level grew more desperate.

Since [the Great Depression] vested interests have been able to roll back many of the progressive initiatives introduced by Roosevelt’s administration in the 1930s—and are still hoping to reverse the few remaining ones, including Social Security.

Unseen Histories

UH: The interwar years on both sides of the Atlantic were socially progressive ones in many ways. The plot in your book springs from a raft of initiatives that were proposed by Franklin D Roosevelt and passed as part of his New Deal legislation. Can you tell us a little about this?

James Shapiro

UH: The interwar years on both sides of the Atlantic were socially progressive ones in many ways. The plot in your book springs from a raft of initiatives that were proposed by Franklin D Roosevelt and passed as part of his New Deal legislation. Can you tell us a little about this?

The Great Depression was a bodyblow to big business. Unemployment was rampant, millions were suffering, and there was a widespread recognition that things had to change.

Since then, at least in the United States, vested interests have been able to roll back many of the progressive initiatives introduced by Roosevelt’s administration in the 1930s—and are still hoping to reverse the few remaining ones, including Social Security. It’s hard to believe, nearly a century later, that there was a time when elected officials believed that the arts, no less than industry and agriculture, deserved government support.

Unseen Histories

Among the various programs introduced by the legislation was the Federal Theater Project, which ran from 1935-9 and is your particular focus. Had there been anything like this before in the United States?

James Shapiro

No. Never. Nor anything like it since. Its productions in those few years, which were free or cost a pittance, reached 30,000,000 playgoers—roughly one in four Americans, two-thirds of whom (audience surveys revealed) had never seen a play before. All for the cost of building a single battleship.

Unseen Histories

You point out that around $7 million was allocated to the FTP, a project that was to be run out of Washington DC rather than the various state capitals. Such a bold cultural initiative seems impossibly daring to us, given the divisions of today. Was it opposed from the very start?

James Shapiro

At the very start it was opposed by pretty much everyone. The commercial theatre world was critical, fearing that these subsidized productions would steal away their audiences. Theatre unions, which didn’t like government usurping their authority, made life difficult for the Federal Theater too. Hard-line leftist critics felt that its progressive productions didn’t go far enough. And of course, reactionaries were appalled by shows, some with interracial casts, that exposed slum landlords, systemic racism, and America’s attraction to fascism.

In retrospect, it’s a miracle the Federal Theatre lasted as long as it did and accomplished so much in those few years.

Unseen Histories

The scope of the FTP was enormous with around a thousand productions being funded in scores of different states. Researching the particular performances must have been hugely enjoyable. Did you find any particular favourites?

James Shapiro

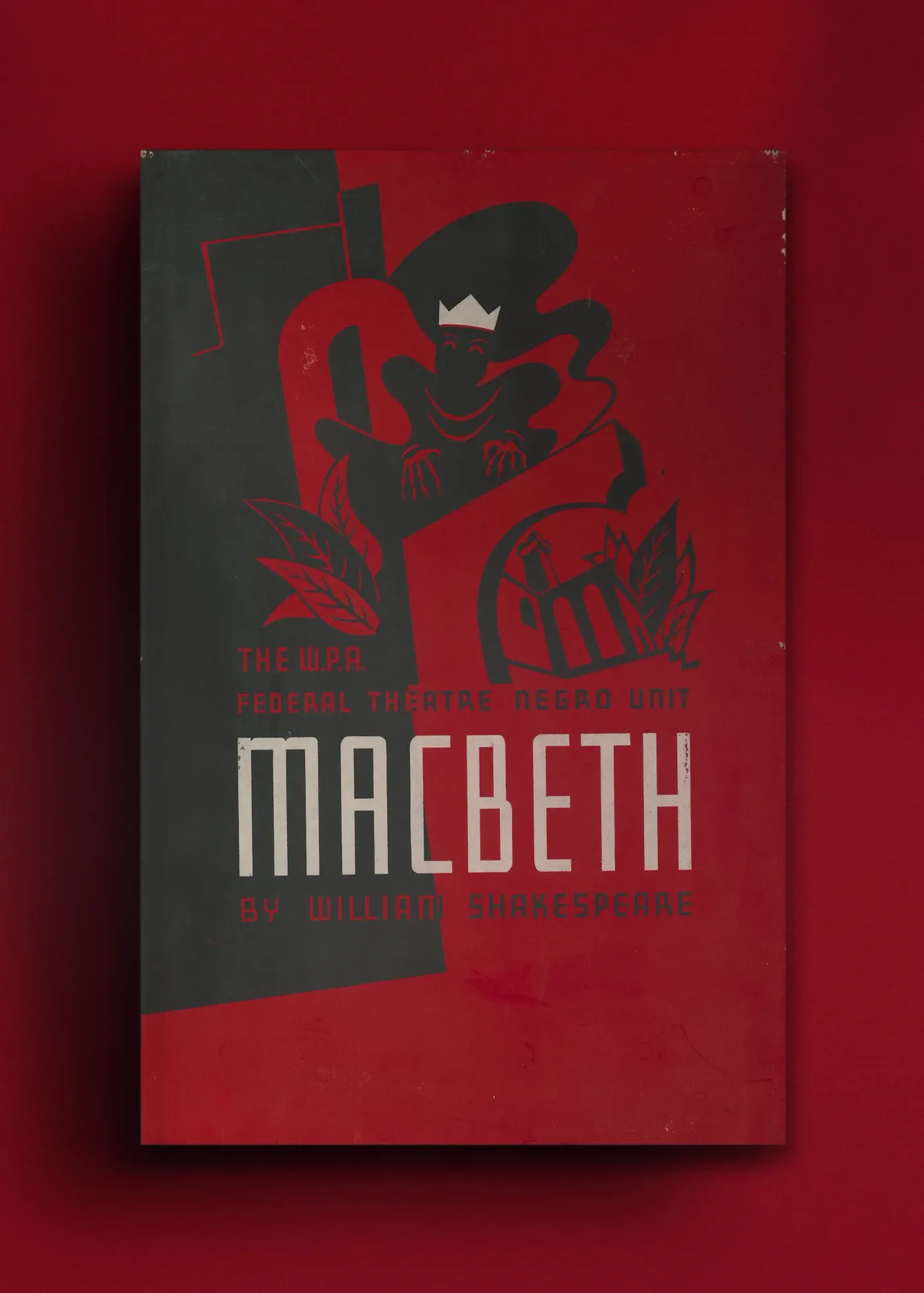

Delving deeply into one of the great Shakespeare productions of the 1930s—the modern-dress Macbeth, set in Haiti and directed by Orson Wells, with a cast of 150 Black performers--was a special pleasure. But the most rewarding play to research was one I had never heard of, the brilliant and savage Liberty Deferred, a factual 'Living Newspaper' that explored the fate of Blacks in America from 1619 to the 1930s. It has never been staged.

Unseen Histories

The events in The Playbook are almost exactly contemporary to the fictional plot of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. This, therefore, is a deeply racist moment in history. Yet you note how the FTP supported Black actors and playwrights. Is this right?

James Shapiro

It’s easy to forget that progressives in Congress at this time could not generate enough support to pass anti-lynching legislation. Yes, the Federal Theatre did set up what it called 'Negro Units' from Hartford, Connecticut to Seattle, Washington. But Whites administered most of these units—and repeatedly sidelined plays that struck them as too radical in calling out systemic racism.

In retrospect, the Federal Theatre could and should have done more; and because it didn’t last long, gains made by Black artists were short-lived as well.

Unseen Histories

The friction in your story is provided by a Texan Democrat called Martin Dies. You note that Dies is very nearly forgotten today. Can you give us a sense of his personality?

James Shapiro

Martin Dies was a ‘good old boy’ from East Texas (where Blacks and poor Whites had no political representation): a tall, handsome, charming, unprincipled, and power-hungry White supremacist who figured out how to exploit emerging media (both radio and newsreels), manipulate the press (which rarely fact-checked or followed up), and bend legislative guardrails.

He also figured out how winning a strategy it could be to label one’s opponents 'un-American.' Much of the political playbook he put together to destroy the Federal Theater is still used by politicians eager to undermine progressive initiatives.

Unseen Histories

The Playbook concludes with the end of the FTP and, you argue, the beginnings of the culture war that divides today’s America. What do you hope that a reader, picking up the book in this embittered election year, will gain from it?

James Shapiro

Readers will learn that there was a time, not so long ago, when Americans across racial, class, and economic divides sat cheek by jowl and watched plays that enriched their lives and spoke to their collective experience.

That could, and should, happen again—but substantial government support for the arts is needed. It’s no accident that theatre and democracy were twin-born in Ancient Greece; the health of one depends on the health of the other 𖡹

His essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, and the New York Review of Books, among other places. He has been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Guggenheim Foundation, and The New York Public Library Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers. In 2011, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He currently serves as a Shakespeare Scholar in Residence at the Public Theater in New York City.

The Playbook: A Story of Theatre, Democracy and the Making of a Culture War

Faber, 6 June, 2024

RRP: £20 | ISBN: 978-0571372768

From the 'Winner of Winners' of the Baillie Gifford Prize, a timely and dramatic story of a utopian American experiment, and the self-serving politicians that engineered its downfall.

1935. As part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's progressive New Deal, the Work Progress Administration is created to support unemployed workers, including writers, artists, musicians and actors. The Federal Theatre Project, a major part of that programme, begins to stage critically acclaimed, subsidised and groundbreaking productions across America, including Orson Welles's directorial debut, a landmark modern dance programme and shows that sought to tell the truth about racism, inequality and the dangers of fascism.

1938. An opportunistic Texas congressman, Martin Dies, head of the newly formed House Un-American Activities Committee, successfully targets the Federal Theatre, exploiting rising tensions over communism and creating a new political playbook based on sensationalism, misinformation and fear - a playbook that has proved instrumental in our current culture wars. From one of the world's great storytellers, The Playbook is an invigorating re-enactment of a terrifyingly prescient moment in twentieth-century American cultural history.

"Some books illuminate the past, some feel vividly relevant to the present moment. The Playbook is one of those rare historical works that does both of these things equally brilliantly. [It] also uncovers the hidden roots of today's culture wars, with all the cynicism, media manipulation and disinformation that shape our current political reality. This is not just a great work of theatre history, it is history itself as a gripping and fiercely urgent drama."

– Fintan O'Toole

"Meticulous and highly researched . What The Playbook richly conveys is something broader than the plight of the Federal Theatre Project, namely America's permanently uneasy attitudes towards race, politics, identity and freedom of speech. Then, as now, this is a country at war with itself: on the one hand, thrillingly progressive, on the other, deeply conservative."

– The Daily Telegraph

Image Credits

With thanks to Kate Burton. Author Photograph © Eileen Barroso