John Barleycorn Must Die

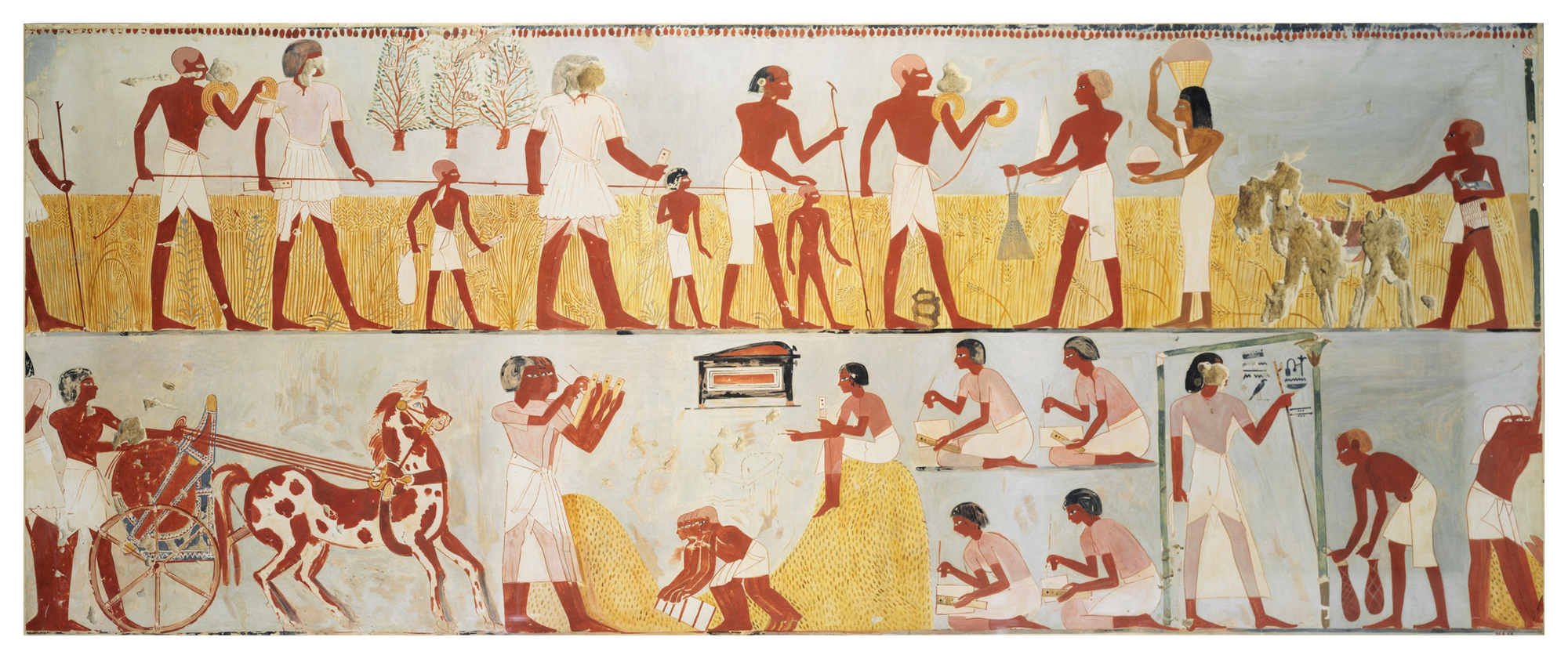

The history and symbolism of harvest festivals

As the summer wanes, in the countryside the fields grow busy. Directly ahead lies the harvest, an event that has always been of critical importance to human societies.

To mark this significance people around the world have long celebrated the harvest in their own distinctive ways.

In this feature Daniel Stables, author of the book Fiesta, looks back at some of the vivid traditions that have long animated this time of the year.

Ever since humans abandoned nomadic hunting and gathering for a settled life of farming around 10,000 years ago, society has proceeded on one hopeful mantra: you reap what you sow. Plant and plough your fields with due care and attention, make the right offerings to the right gods at the right times, and food, for the most part, barring the odd famine or biblical plague, will find its way to the table.

Over time festivals have come to play a part in the ritual apparatus which surrounds harvest time – celebrating a good crop, staving off a bad one for the next year, handing out surplus in times of bounty to those less fortunate than ourselves. And the fact that the harvest arrives at different times of year across the world means that there is always a harvest festival, of some kind, going on somewhere.

Archive photographs taken at harvest time in rural communities in Britain in the early twentieth-century show terrifying human-sized corn effigies, their ‘heads’ and ‘hands’ bursting from the sleeves and neck holes of white nightdresses, propped up against trees and on church benches.

To this day, if you visit Cornwall during harvest time, you might witness a tradition known as Crying the Neck, in which the year’s last sheaf of harvested corn – the ‘neck’ – is cut with a scythe and presented ritualistically by the farmer to a gathered crowd, initiating the following call-and-response exchange:

Farmer: "I have'n! I have'n! I have'n!"

Crowd: "What have ee? What have ee? What have ee?"

Farmer: "A neck! A neck! A neck!"

Crowd: "Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!"

The way that harvest festivals have manifested themselves across cultures and across history are, like all forms of festivity, varied, vibrant, and often baffling.

Observant Jews mark the harvest festival of Sukkot by spending a week eating and sometimes sleeping inside a sukkah, a hut made from canvas and wood which represents the tabernacles used by the Biblical Israelites in the wilderness.

Foods eaten at this time include challah bread and cabbage rolls, and the sukkah is decorated with the produce for which Israel is celebrated in Deuteronomy – 'wheat and barley, vines and fig trees, pomegranates, olive oil and honey' – and white sheets, representing the clouds of glory which shrouded the Israelites during their wanderings in the desert.

Which is not to say the sukkah is a monolith, frozen in time. It has modern manifestations, too. In 2009, the Bet Shira Synagogue in Miami set up a drive-through sukkah – the ‘McBet Shira’ – so that busy members of the congregation could fit in a few minutes’ eating or worshipping during their busy day.

Harvest is the time when humans reap the bounty of the land, but sometimes it has also been the time for governments to reap a financial harvest from their subjects.

In Ancient Persia, during the days of the Achaemenid Empire (550–30 BCE), the autumn harvest festival of Mehregan was celebrated in lavish style at the capital of Persepolis, with six days of feasting alongside the paying of tax, with people from across the empire bringing with them the gold coins they owed their king.

Food was also brought to be donated to the poor, a feature of harvest festivals to this day. Primary school children across Britain are encouraged to bring in what their family can spare for donation to the community – tins of beans, dried noodles, peanut butter, bags of rice Mehregan was originally a Zoroastrian festival, held in honour of the deity Mithra.

But even in modern Iran, where more than 90% of the population are Muslims and Zoroastrians have been persecuted for centuries, the voice of the pre-Islamic past rings loud and clear. Mehregan altars nationwide bear the same adornments: pomegranates, apples, bottles of rosewater, a mirror, and a copy of the Khordeh Avesta, the Zoroastrian holy book.

The survival and co-opting of ancient religious traditions is a feature of festivals, and never more so than during harvest time.

The Gaelic festival of Lughnasadh, held on 1ugust, marks the beginning of harvest season and was traditionally celebrated on mountaintops, with the sacrifice of a bull, ritual dances, and a ceremony known as the First Fruits, in which the first produce harvested from the fields was presented and ritually blessed.

It is unlikely to be a coincidence that on the very same day of the year, Christians celebrate Lammas, which involves bringing a loaf of bread baked from the year’s first wheat crop into the church in order to be blessed. In a neat continuation, some Neopagans have in turn taken to calling their modern-day celebration of Lughnasadh ‘Lammas’.

Pre-Christian Lughnasadh celebrations – particularly the practice of making pilgrimage to the tops of mountains – are believed to contain the origins of one of Ireland’s great surviving festivals. The Puck Fair is held each 10–12 August in the Co. Kerry town of Killorglin, after townsfolk have ascended into the MacGillycuddy's Reeks mountain range, captured a feral male goat, and returned him to the town.

In what is believed to be a nod to pagan fertility rituals, the goat is crowned ‘King Puck’ and displayed in a cage in the town square while horse and cattle fairs take place below, alongside much revelry.

The event is believed to have continued largely unchanged since at least the 1600s – although King Puck is nowadays only displayed for a couple of hours, rather than the full three days, to assuage animal rights concerns.

In Europe and North America, the Celtic festival of Samhain, which marks the end of harvest season, has been transmuted in the Christian era into Halloween, but it retains its basic atmosphere as a time when the veil is thin between our world and the next, and all manner of demons and ghouls, not to mention the spirits of the dead, are able to slip temporarily into our earthly realm.

You might imagine that such ghoulish associations have less to do with the harvest and more to do with the lengthening and darkening of the night, and the arrival of colder weather – a time for huddling together and telling ghost stories. But harvest festivals have similar connotations even in countries where the harvest does not necessarily herald the coming of cold, dark weather.

Across East and Southeast Asia, late summer and early autumn is the time of the Ghost Festival, a month in which the spirits of the ancestors are believed to visit the living, and are welcomed by the burning of incense and joss paper.

There is a widespread belief that the spirits can interfere with human affairs, to the extent that important surgeries, business deals and other important life events should be avoided during this time – even in super-sensible Singapore, the housing market slumps during Ghost Month.

It is, perhaps, not a coincidence that many festivals of death, the afterlife and the otherworld coincide with the harvest. As in the case with corn dollies and the figure of John Barleycorn, the harvest is a time of symbolic sacrifice – the crops die so that we might live, and the circle of life goes on •

This feature was originally published August 14, 2025.

He has won acclaim and recognition for his work, having been shortlisted for Travel Writer of the Year at the Freelance Writing Awards in 2021, and for Travel Feature of the Year at 2023's British Guild of Travel Writers awards.

Fiesta: A Journey Through Festivity

Icon, 14 August, 2025

RRP: £20 | 288 pages | ISBN: 978-1837732517

A journey through human festivity, told through colourful travel narratives set at some of the world's most eye-catching festivals and interweaved with insights from the fields of anthropology, history, psychology, and folklore, examining why we celebrate festivals in the ways we do.

Fiesta explores the vibrant tapestry of human festivity, delving into the extraordinary lengths to which we go to express our cultures and commemorate life's milestones.

From drunken pilgrimages to sacrificial funerals, national days to neo-pagan necromancy, festivals represent human culture at its most vivid and varied, and the resulting account is both a rich collection of travel writing and an anthropological exploration of the roles that festivals play in society. Through colourful characters, vibrant sights, and varied locales, Daniel Stables takes a curious, humanistic look at festivals across the world, unravelling the universal threads that run through our diverse global celebrations.

“Alternately rollicking and reflective, Fiesta profiles the most fascinating and eye-catching festivals around the world - and what they reveal about the human need for ritual and connection”

― BBC Travel

With thanks to Elle-Jay Christodoulou.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store