Lord of the Flies and the Second World War

Dr Nicola Presley traces the hope and despair of William Golding's novel back to the years of war

Ever since its publication in 1954, William Golding's novel, Lord of the Flies, has retained a powerful presence in English literature.

In his allegorical debut, Golding portrays a nightmarish vision of humanity gone astray. The story follows the experiences of a group of British children who find themselves stranded on a deserted island.

The inspiration for the troubling events that ensue, Dr Nicola Presley argues here, can be found in Golding's own wartime experiences.

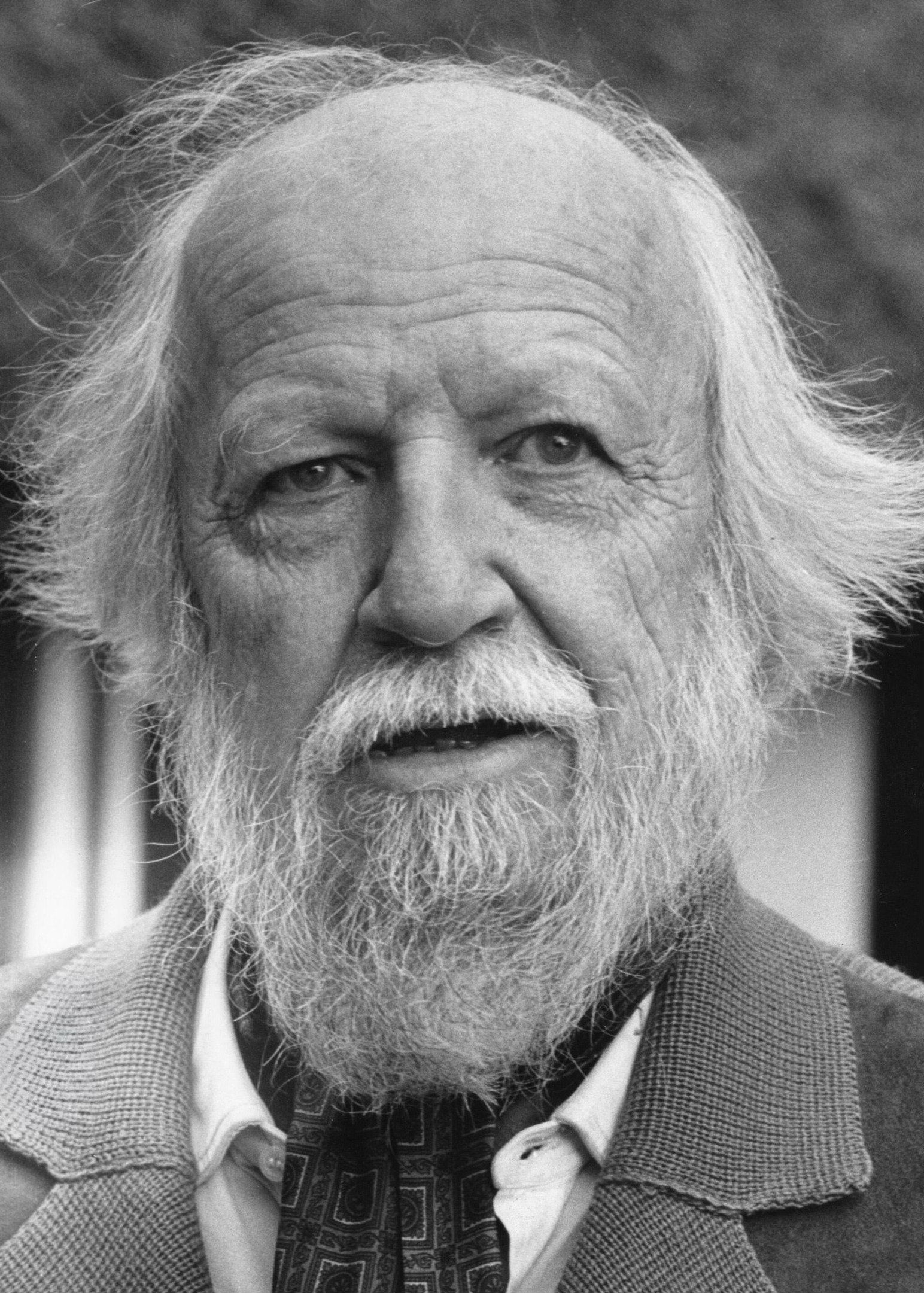

William Golding (1911–1993) was a schoolteacher at Bishop Wordsworth’s School in Salisbury, Wiltshire at the outbreak of the Second World War. He joined the British Navy as an ordinary seaman in December 1940 at the age of 29 – significantly older than the majority of his colleagues, a situation which he found particularly difficult. By the end of 1941, he had applied for a commission, and was eventually promoted to lieutenant.

By this time, it was clear that although working as a schoolteacher, Golding's aim was to be a writer. In 1934, his collection of poetry, simply titled Poems, was published by Macmillan, although he had no success with his prose.

Golding continued to write during the war. Much of this work remains unpublished but his memories often surface in his later non-fiction. For example, in 1961, Golding wrote an essay, ‘The English Channel’ for Holiday magazine, also now available in his collection The Hot Gates.

In this he describes flying over the English Channel on D-Day, and envisioning the fleet of thousands of ships en route to the landings:

‘Indeed the Channel was big that night, oceanic, and covered with a swarm of red stars from planes and gliders moving south. I found that we were miles west of our position. So we turned southeast and steamed at full speed all night over jet black waves that were showered with sparks of phosphorescence and possibly loaded with mines.

I stood there all night catching up and felt history in my hands as hard and heavy as a brick.’

This experience, he later said, was the ‘great formative influence in my life’. At the end of the war, Golding returned to teaching and to writing fiction. Scribbling in school notebooks in breaks and even during lessons, Golding’s first published novel Lord of the Flies began to take shape in 1951 and the first version was completed in 1952.

It’s clear that following his own experiences during the war and the wider atrocities that occurred, Golding recognised that humans were capable of acts of unimaginable violence and hatred.

In Lord of the Flies, he explores what he called the ‘terrible disease of being human’, and as he wrote in his essay ‘Fable’, he ‘had discovered what one man could do to another.’ In particular, Golding was disturbed by the actions of what he called ‘ordinary’ men, who perpetuated these acts of violence.

In the allegorical Lord of the Flies, this is represented by the shift in the behaviour of certain boys as their connections to civilisation unravel.

Perhaps the most terrifying of all the boys is Roger, who pushes at the boundaries of acceptable behaviour from the early parts of the novel. Roger watches the ‘littluns’ playing on the beach and his ‘unsociable remoteness’ turns into ‘something forbidding’.

Then, Roger follows another boy, Henry, as he wanders off on his own. As Henry is swimming, Roger begins secretly throwing stones, meaning them to miss, near to Henry in the water. He dares not throw them directly at Henry – ‘Roger’s arm was conditioned by a civilisation that knew nothing of him and was in ruins’.

This intimidation – just on the edge of violence – gives way to his shocking murder of Piggy at the end of the novel. It’s particularly poignant since it is Roger who first suggests that the boys should have a democratic vote for leader shortly after the plane wreck – this initial commitment to social order degenerates into something much darker.

While Roger can eventually be classified as an enemy to democracy, and is clearly on the ‘bad’ side of the boys’ island war, Golding also subtly explores the complexities of character of those who we might think of as our heroes.

In this interview, Golding explains that in Lord of the Flies, Ralph undergoes his own Second World War. He loses his innocence – or ‘ignorance’ as Golding calls it – about the true nature of humanity. Elsewhere, Golding suggests that he and his fellow soldiers were all ‘Ralphs’ or ‘Piggys’ before the war began; decent people who believed in the rule of law and order.

But despite the ostensible goodness of Ralph and Piggy, both are involved in the murder of Simon. They join Jack and his hunters for a gathering on the beach, and in the highly charged atmosphere, Simon is mistaken for the beast as he emerges from the forest. Amidst cries of ‘Kill the beast! Cut his throat! Spill his blood!’, Simon is brutally beaten to death by all the boys.

In an uncomfortable subsequent scene, Piggy and Ralph both try to downplay their culpability, although Ralph struggles to explain how he felt: ‘I wasn’t scared […] I don’t know what I was’.

What Ralph is unable to articulate here is his excitement and the sheer sense of power he felt as part of the group; how the shared emotions of hate and fury united them into a force of sadistic evil.

These book jackets show some of the ways in which Golding’s novel has been portrayed over time.

Golding demonstrates the relative ease with which good people can be drawn into wickedness and savagery, a direct reflection of what had occurred in the war.

It’s important to note, too, that Golding himself felt that he could have been one of those people, as detailed in some of his unpublished writings and numerous interviews, including his famous quotation that ‘man produces evil as a bee produces honey’.

The war, he said, had ‘altered’ him. He later wrote: ‘My book was to say: you think that the war is over and an evil thing destroyed. You are safe because you are naturally kind and decent. But I know why the thing rose in Germany. I know it could happen in any country.’

The end to the terror on the island only comes about by the arrival of an adult, a naval officer who stops the final breath-taking chase of Ralph by Jack and his tribe.

In this moment, Golding’s allegory is fully realised. The reader sees the characters through the eyes of the officer, who describes them as they are: a group of very young boys, filthy, injured, and in desperate need of adult intervention.

This is in stark contrast to the monsters intent on murder we’ve spent the last two hundred or so pages with, where it is easy to forget the fact that these are children. The officer is disappointed in their actions and says that ‘I should have thought that a pack of British boys […] would have been able to put up a better show than that’.

However, as he eyes his ‘trim cruiser in the distance’, he is seemingly oblivious to the parallels between his adult war and the war on the island. Golding here exposes the dangers of totalitarianism, and the needless human cost of warfare.

Lord of the Flies is an allegory on the breakdown of civilised society and the subsequent desperate and brutish struggle for power. The book was born out of Golding’s experiences in the Second World War, and his fears about the aftermath, with the threat of nuclear annihilation haunting the pages.

But it is not without hope. At the beginning of the novel, Ralph stands on his head in sheer delight at the beauty of the island, a world unspoilt by human intervention. At the end, he remembers a ‘true, wise friend’. There is optimism here too – in nature, in friendship, and in peace •

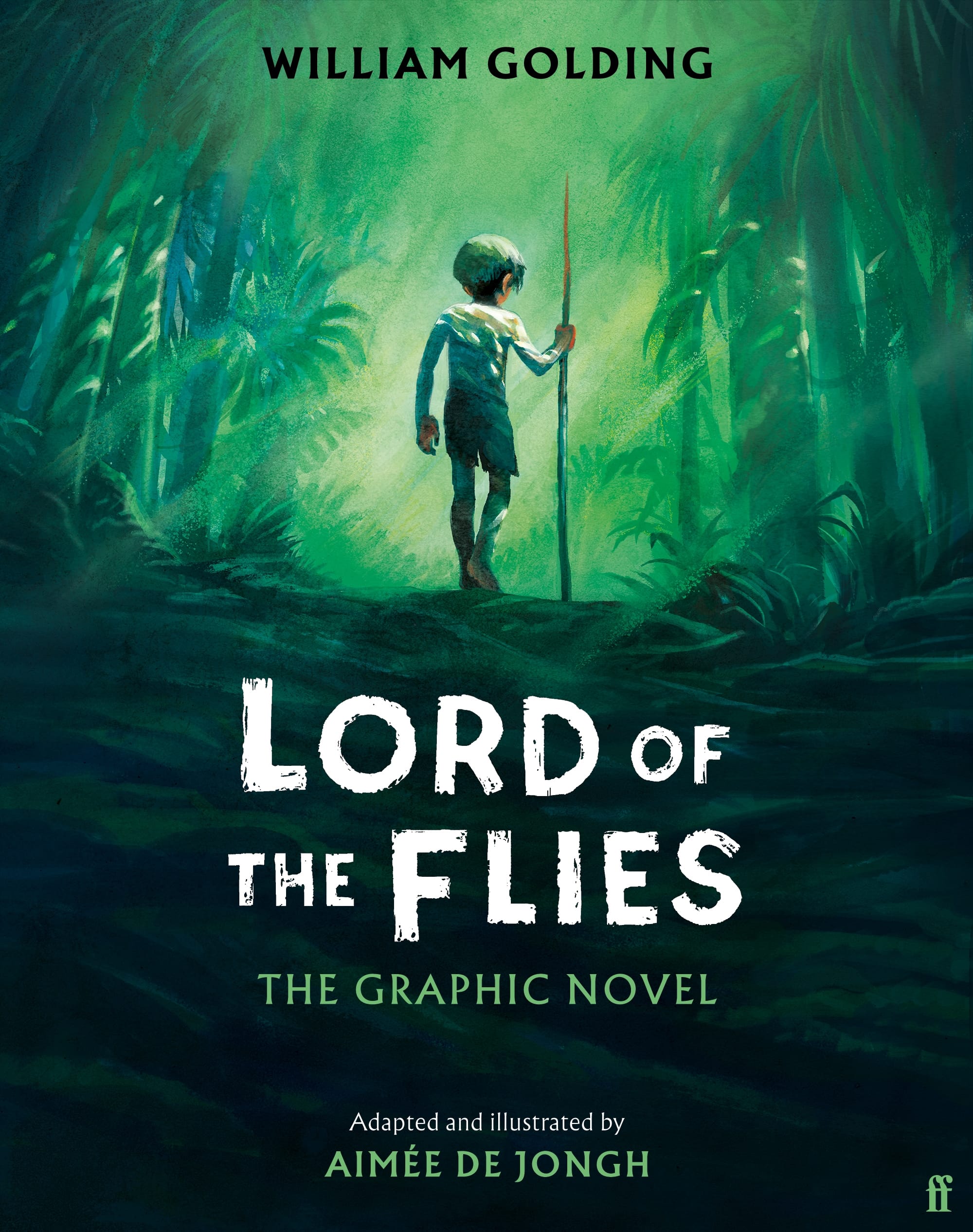

This feature was originally published November 14, 2024 around the publication of a new deluxe version of Lord of the Flies, with an introduction by Stephen King. In September, for the first time ever, a graphic novel of Golding's story was published with illustrations from Aimée de Jongh.

This feature was originally published November 14, 2024.

Lord of the Flies: Deluxe Anniversary Edition

Faber & Faber, 7 November, 2024

RRP: £20 | 256 pages | ISBN: 978-0571390762

“The first book with hands - strong ones that reached out of the pages and seized me by the throat. It said to me, 'This is not just entertainment; it's life or death'. . . I've been thinking about it ever since, for fifty years and more” – Stephen King

‘There aren't any grown-ups anywhere.’

A plane crashes on a desert island. The only survivors are a group of schoolboys. By day, they explore the dazzling beaches, gorging fruit, seeking shelter, and ripping off their uniforms to swim in the lagoon. At night, in the darkness of the jungle, they are haunted by nightmares of a primitive beast. Orphaned by society, they must forge their own; but it isn't long before their innocent games devolve into something far more dangerous . . .

With thanks to Arabella Watkiss.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store