Meet me at the Cemetery Gates

Little spaces, profound stories. Roger Luckhurst tells us about London's hidden cemeteries

While it is a seldom acknowledged fact, today's Londoners live among the dead.

Many of today's parks were once cemeteries, the raised platforms of children's playgrounds suggests they were once used as burial grounds. All this becomes clear, once you know where to look.

Roger Luckhurst, the author of Graveyards, tells us more about this here. And he takes us to one of London's most evocative places: the St Pancras Old Church.

I have always been interested in inner-city graveyards, not just those ostentatious survivals like Highgate in London or Greyfriars in Edinburgh, but the quieter ragged gated squares or scruffy corners of grass, perhaps with only one or two remaining chest tombs or a fringe of headstones moved out of the way to serve as decorative edges. Even these tiny spaces crammed into an acre or less can have richly storied pasts, often with enough material to fill a book themselves.

Many city dwellers discovered these little spaces in lock-down: I often had a coffee in a small local park in London with a life-saving open coffee hut that I gradually unearthed had once been a pauper burial ground for the Irish workers of the surrounding rookeries and then, until it was bombed in the Second World War, housed the City of London’s local morgue.

Not a single monument remains (paupers were buried in pits, often twelve coffins deep, with no headstones), but the park still has that feeling of sitting curiously out of time. The old burial grounds fold centuries into the pockets where they stand, even as modern developers nibble at their edges.

Most inner-city burial grounds were closed for new interments in Britain in the Burial Acts of the 1850s and reformers pushed for garden cemeteries at the edges of towns. Any burial grounds that survive in London can usually credit their survival to a group of activists in the 1880s and 1890s.

The Metropolitan Public Gardens Association wanted to respect the memory of the dead while also transforming disused burial grounds into little oases of Nature to aid the health of the population, particularly those crammed into dense slum housing.

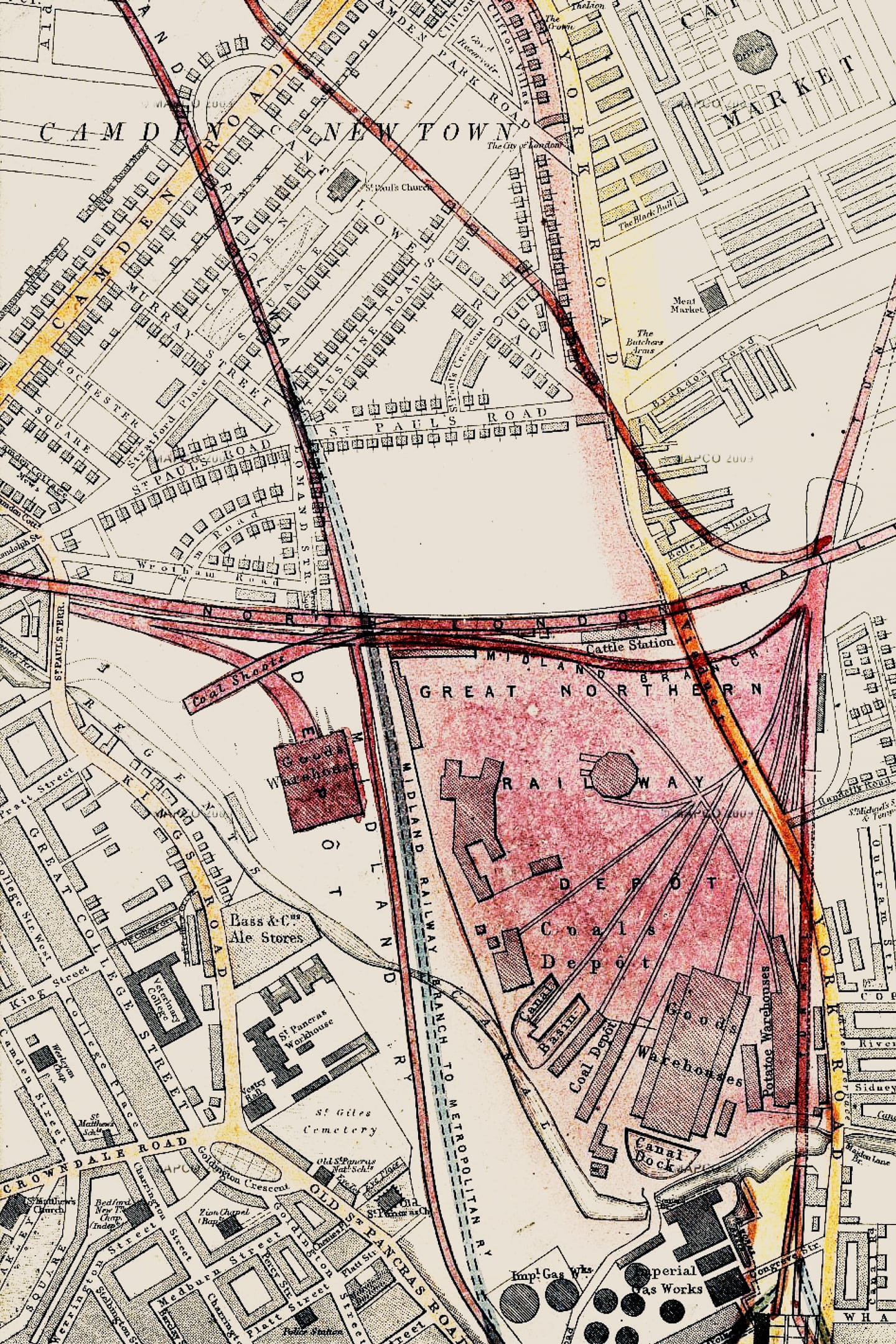

In the 1890s, the redoubtable Isabella Holmes of the MPGA took it upon herself to visit and document over 350 burial grounds in London using old maps and local knowledge. Many had already been lost, built over, or converted into storage grounds: she blustered her way through many locked gates and high walls to record those still clinging onto existence. Her 1896 gazetteer is still a helpful guide to the urban wanderer.

Many pocket parks that are lively playgrounds now were once deeply melancholy sites. On Seward Street in Clerkenwell, the swings and climbing frames sit between the housing blocks. That the ground of the park is about five feet higher than the street is a tell-tale sign of over-burial, when bodies continually covered with new layers of top soil to allow for ever more burials in confined spaces.

This was an overspill ground for the unclaimed paupers of St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Just down the road, there are a few scattered chest tombs in the grounds of St Luke’s Church, now magnificently restored but for decades a shattered ruin. The narrow strip of a park beyond was once the graveyard for the Pauper Asylum that loomed over Old Street, but there are no traces of that left.

These battles for survival are still ongoing. The Cross Bones in Southwark, on the south side of the River Thames, is a provisional space, long used by London Transport for storage and prime territory for lucrative development. But it has recently been reimagined as the Cemetery of the Outcasts by activists and campaigners fighting for its preservation.

History suggests that this was the ground where ‘fallen women’ were buried. The so-called ‘Winchester Geese’ were sex-workers unofficially allowed to work in the brothels beyond the old walls of the City by the Bishop of Winchester.

Since 2004, the volunteer Friends of the Cross Bones have preserved this provisional space and turned it into an urban garden, and the long iron railings have become decked with thousands of memorial ribbons and mementos of the ‘outcasts’ of the City. The place keeps a dissident and punkish atmosphere of defiance as the pressure for development so close to the financial centre works to take the territory.

Another famous churchyard further north is also used to losing ground. The atmospheric gloomy churchyard around St Pancras Old Church lost some land to the Victorian railways when they opened St Pancras station.

More recently, redevelopment for the Eurostar trains also meant a trim to one of the oldest burial grounds in London. Passengers pulling out of the station have a brief glimpse of the graves under the old trees, perhaps unaware of the millennia of history associated with the site.

St Pancras Old Church has laid claim to being one of the oldest Christian churches in England, stretching back to the fourth century, not so long after the martyrdom of Pancras in heathen Rome.

Does the church occupy the site of a Roman temple? There is little evidence beyond the speculations of many generations of antiquarians, but a Christian church has certainly been on the site since the Domesday Book. After the Protestant split from Rome, the churchyard remained one of the few places where Catholics could still be buried in sanctified ground.

Hemmed in by railway lines and looming Victorian hospital buildings, this place has a particularly rich network of literary association. The teenage poet and forger Thomas Chatterton made himself the poster child for Romantics by taking his own life in 1770, only three days after falling into a freshly dug grave in the churchyard. Thirty years later, the radical feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft was buried here, having died of complications giving birth to the girl who would become Mary Shelley.

Mary remembered being taught to read by her radical father William Godwin by picking out the letters of her mother’s name on her headstone (which can still be visited). Later, Mary used the visits to the grave to have assignations with the young scamp, Percy Shelley. One biographer has claimed that the weeping willow at the graveside gave cover for Mary and Percy to consummate their passionate affair. Soon after they eloped.

In Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), there are several visits to graveyards. Mary began to write the novel after that famous ghost story contest with the entourage of scandalous Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. Byron’s doctor, William Polidori, had joined in and later published the short story The Vampyre, assumed to be the confession of the devilish Lord Byron himself. The unlucky Polidori was soon dead himself – and buried in the St Pancras ground in an unmarked grave.

After the churchyard was closed to new burials in the 1850s, the church fell into disuse and ruin. But when rapid urbanisation increased the population again, the church was rebuilt and the burial ground redesigned.

In the 1860s, a young architectural apprentice grouped together some of the discarded gravestones and placed them around the base of an ash-tree. The apprentice was Thomas Hardy, who became much preoccupied with the dead and their ghostly traces.

The monument at the edge of the grounds seemed at risk from the massive works for the Eurostar. It survived but it seems symbolic of something about our age that Hardy’s ash finally fell in 2022.

There are many believers that certain places condense occult forces: we sometimes call them genius loci. William Blake, the visionary Romantic who conversed with the spirits of the dead and angels in trees, was drawn to St Pancras church. His descendant is the poet Aidan Andrew Dun, who claimed to have a visionary experience in 1973 in a street near the graveyard.

This was a communication from the French Decadent poet Arthur Rimbaud, whom, it turned out, had lived in the same streets for only a matter of weeks exactly one hundred years before. Dun’s cracked visionary poem, Vale Royal, which took him over twenty years to write, is steeped in Blakean Romantic mysticism, bringing all the archaeological layers of the tiny ground of St Pancras Old Church back into simultaneous existence.

It is these moments of overlaid history that make for modern urban magic: this is the atmosphere many of us sense in these cemetery heterotopias, these ‘other spaces’ that allow us to step out of time •

This feature was originally published October 21, 2025.

Graveyards: A History of Living with the Dead

Thames & Hudson, 2 October 2025

RRP: £30 | ISBN: 978-0500027707

An arresting and poignant cultural history of graveyards, from early burial sites to now.

Why, how and where do we inter our dead? How do we set out to remember them? The Pyramids of Giza, the catacombs and columbaria of Rome and the cenotaphs erected to the world’s war dead are but some of the answers. In inimitable style, Roger Luckhurst probes the often moving, sometimes contested ways in which people throughout history have responded to the ‘problem’ of laying the dead to rest.

Blending history, art, literature and popular culture, Graveyards explores the various different aspects of the treatment of the dead. Chapters range from early burials and the emergence of necropolises and catacombs, to grave-robbing, garden cemeteries and the perilous overcrowding of the urban dead, to monuments for deceased heroes and rulers and the development of modern memorial culture. The products of our persistent fascination with graveyards are everywhere in literature, art, film and television, and Luckhurst engages these cultural afterlives alongside grave sites’ particular social and historical contexts.

With thanks to Caitlin Kirkman.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store