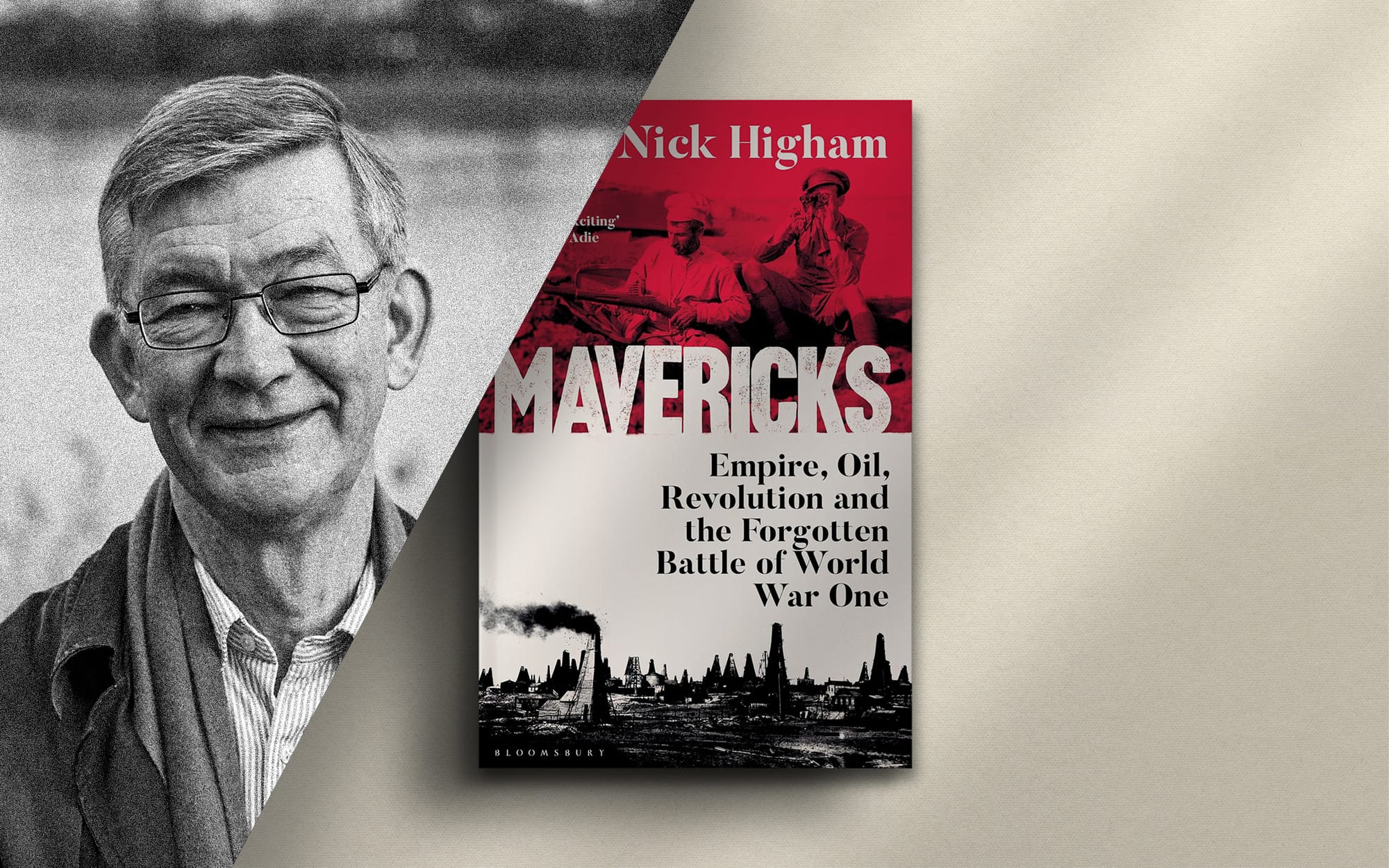

Meeting the Mavericks

Nick Higham tells us about his vibrant cast of British servicemen who fought to save Baku from the Turks in 1918

We tend to have a narrow view of the First World War today. This is one dominated by shells, mud and trench-bound misery.

But as Nick Higham shows in his new book, Mavericks, there were other parts of the conflict that were full of dynamic action.

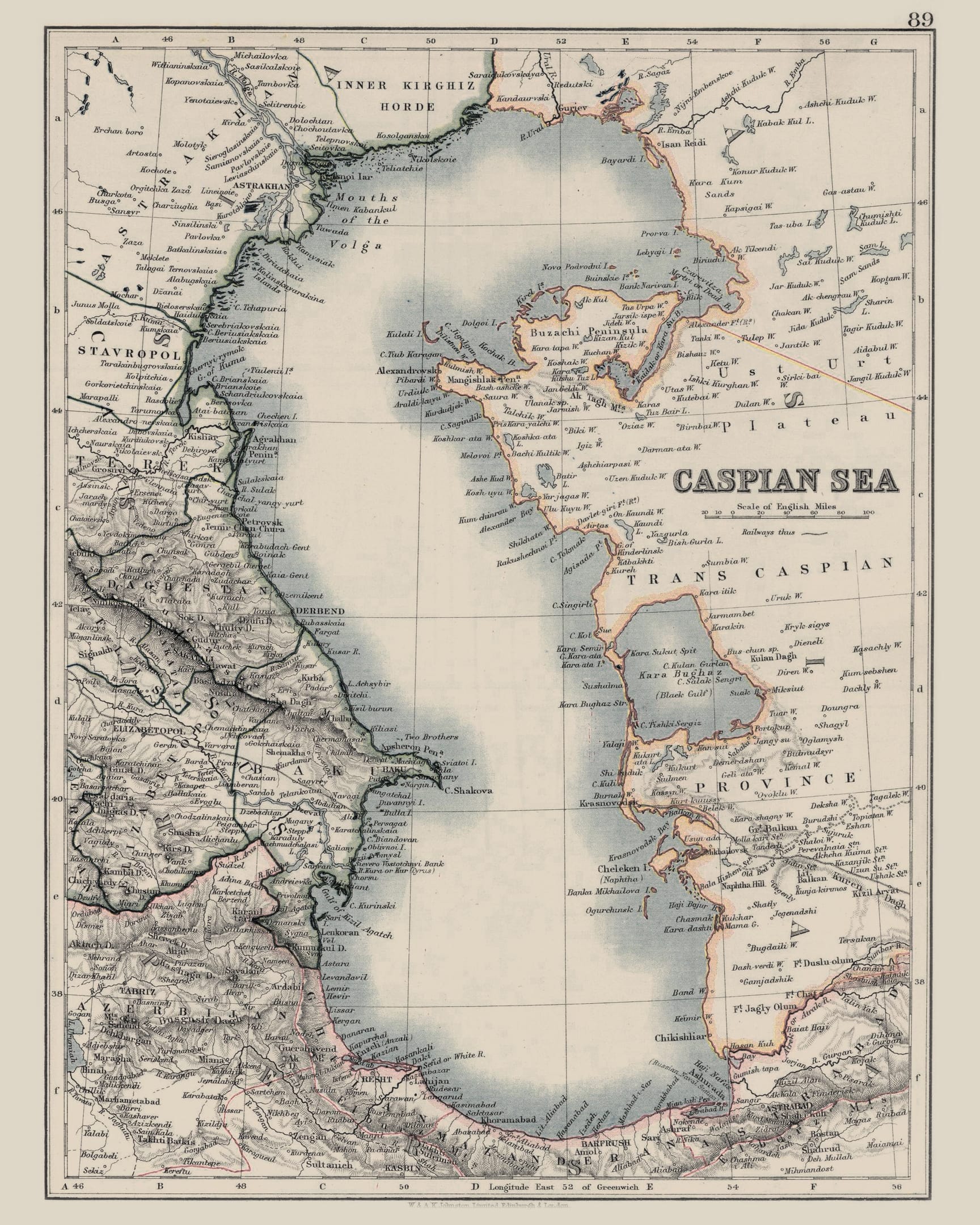

A particular example of this, Higham explains, were the British military operations that took place around the oil fields of Baku on the edge of the Caspian Sea.

Questions by Peter Moore

Unseen Histories

Your last book, The Mercenary River, examined the history of London’s water supply. What took you from this to your new book. Mavericks, which is set around the Caspian Sea?

Nick Higham

I’ve wanted to write this story for years, ever since I came across footage that one of my five central characters shot in 1928 of his pioneering drive from Bombay to London.

There were shots of him and a colleague in their pith helmets digging the car out of the desert sands in Persia – most of Persia had no proper roads in those days – and driving gingerly round dead camels, and I wanted to know more about a man who would do something so unusual.

When I discovered his back story – and that he would later go on to publish his first book at the age of 99 – I was hooked, and doubly so when I realised there were several more like him and they’d all been involved in the Battle of Baku.

Unseen Histories

We’re used to thinking of WW1 as a static conflict defined by trench warfare. Mavericks shows us a connected but much more dynamic history. Can you tell us a little about it?

Nick Higham

Static trench warfare was a phenomenon of the Western Front: the war elsewhere was much more mobile.

That was especially the case when, following the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917, the armies of Tsarist Russia collapsed – they basically downed tools and went home.

Lenin and Trotsky agreed an armistice with the Germans, but in the Caucasus, where Russia had been fighting the Ottoman Empire, it suddenly meant there was no Russian army to resist the Turks or prevent them moving eastwards to seize Baku. That’s how my chaps came to be there, in a desperate effort to save Baku from the Turks.

Unseen Histories

People might think of the Russian revolutions of 1917 as being distant events. But to many in Britain at the time they seemed much more immediate and politicians were determined to respond. Is this correct?

Nick Higham

To begin with politicians in Britain were blindsided by the revolution. There were the immediate strategic problems caused by the Russian military collapse, of course. But beyond that nobody really knew who these Bolsheviks were – a widely-held view was that they were part of a Jewish-German conspiracy to take Russia out of the war. Should the Bolsheviks’ rhetoric about global revolution be taken seriously? Were they just a temporary phenomenon?

For many months Britain tried to have it both ways: it wouldn’t recognise the new government officially, but opened unofficial channels of communication and occasionally co-operated locally with the Bolsheviks. That only hardened into outright opposition in August 1918, ten months after the revolution; Winston Churchill understood clearly what the Bolsheviks were about, but many of his colleagues thought he’d lost the plot, so virulent was his anti-communism.

Unseen Histories

If water is the natural resource that runs through your first book, is oil the one that flows through this? Where was this oil and was the collective ‘West’ aware of the importance of it as a natural resource at the time?

Nick Higham

Baku’s importance lay in its enormous oil reserves (in 1900 half the world’s oil had come from Baku) and after 1914 oil was essential in waging war, for fuelling ships and motor transport. The British effectively nationalised the Anglo-Persian Oil Company in Abadan in 1914 in recognition of this.

When Lionel Dunsterville was despatched to the Caucasus in January 1918 (ironically in a convoy of 41 Ford vans and cars which had to carry most of their fuel with them in jerry cans all the way from Baghdad), keeping this vital resource out of the hands of the Turks and Germans was a high priority.

When he finally got there in August the strategic situation had changed, but his tiny force, 1,200 strong, nonetheless played a key role in keeping a Turkish army occupied for six weeks while Turkish resistance collapsed elsewhere.

Unseen Histories

The historian Matthew Parker has identified 29 September 1923 as the day when the British Empire reached its greatest territorial extent. Your story is set in the years just before this. Was this a time of supreme imperial confidence?

Nick Higham

The Empire might have been even larger. Much of Persia, nominally independent, was gradually turning into a branch of the Indian Empire from 1907, and the men on the ground in Transcaspia (the modern Turkmenistan) in 1918-19 were propping up a local anti-Bolshevik government which might have become a British protectorate.

But it would have required the long-term deployment of troops and after four years of war there wasn’t the money or the political appetite for that. We can assume that all my central characters were gung-ho imperialists; but in retrospect you can see the decision to withdraw from Transcaspia as the moment when Britain’s imperial self-confidence started to falter.

Unseen Histories

This was also a time filled with the daredevil spirit with the motor races at Brooklands, the Schneider Cup, Mallory’s Everest expeditions and so on. One of your characters, Toby Rawlinson, is an example of this culture, isn’t he? Can you tell us a little about him?

Nick Higham

Toby was the younger brother of Henry Rawlinson, one of the British army’s most senior generals; he himself left the army to pursue his real passion, which was dangerous sports.

He won an Olympic gold in polo in 1900, he was an aviation pioneer (Royal Aero Club pilot’s licence no 3) and a racing driver, who took his brand new Hudson racing car to France in 1914 to ferry British staff officers around the countryside: he mounted his personal machine gun on the bonnet and two captured German pickelhaube helmets on the mudguards and a photograph shows several bullet holes in the bodywork.

Later he set up London’s first anti-aircraft defences and then served as a colonel in Dunsterville’s little army. If Baku hadn’t been evacuated he was poised to mount a daring motorised raid behind enemy lines to blow up railway bridges, which would have prefigured exactly the exploits of the Long Range Desert Group and SAS in North Africa in World War Two.

He was insufferably hearty and probably a bully but unquestionably brave and I can’t help liking him.

Unseen Histories

Rawlinson is one of your central characters. But there are four others too. Which of them did you most enjoy reviving and why?

Nick Higham

Which of my babies do I love most, you mean? Dunsterville was probably the nicest of them and the most entertaining. He’d been at school with Kipling and was the model for the mischief-making ring-leader in Kipling’s Stalky & Co school stories.

Aeneas Ranald Macdonell, Britain’s vice-consul in Baku, ran him close for charm and was a great (if not always reliable) story-teller. Edward Noel, soldier, diplomat, spy, agricultural reformer, opium addict, enthusiast for alternative technologies, was a legend among his contemporaries for risk-taking and enterprise, but only made it to Baku in the last days of the battle after being freed from five months held hostage by jungle terrorists: all that time in solitary, several failed escape attempts and a mock execution left him psychologically damaged.

Reginald Teague-Jones, who made the film in Persia which started me off, was the most mysterious of them – and went to his grave still carrying a secret he’d kept for 60 years.

Unseen Histories

How aware were the general public of the operations that were happening in the Caspian theatre?

Nick Higham

Dunsterville’s mission was undertaken in great secrecy. Those in the know referred to his little force as the “hush-hush army”. Its existence was only revealed when it reached Baku, when there was much enthusiasm in the press over such a daring thrust hundreds of miles across Persia – only to be followed by predictable recriminations when “Dunsterforce” had to evacuate six weeks later.

Unseen Histories

You admit that much of the source material you had was unreliable. You also confronted the problem of anti-Semitism in writings by Reginald Teague-Jones. How did you respond to such challenges?

Nick Higham

When I started I tended to accept what my characters wrote in their memoirs at face value. I quickly realised that was naïve – but even so I was taken aback by the extent to which Teague-Jones in particular simply made stuff up and passed it off as fact.

Part of the book is devoted to getting to the bottom of what was true and what was invented. The anti-Semitism was shared by all these men and was typical of the era, and helps to explain their assumption that Bolshevism was a Jewish plot.

It’s important to acknowledge its existence, but I silently edited out some gratuitously anti-Semitic remarks when quoting, so as not to distract the contemporary reader.

Unseen Histories

The historian Jonathan Schneer, in The Lockhart Plot, has pointed out how much of Russia’s distrust of the British today can be linked back to the interventions of this time. Did writing Mavericks leave you with a similar feeling too? You write, after all, that there ‘are no final endings in history.’

Nick Higham

After August 1918 the Allies intervened to try and snuff out Bolshevism and fuelled a brutal civil war, so Russia’s attitude isn’t surprising. But Soviet historians misrepresented what happened. It was part of the Soviet Union’s origin myth that the dastardly imperialists were bent on strangling Bolshevism at birth, from the very moment of the revolution, whereas writing Mavericks I was struck by how the allies really stumbled into the intervention almost accidentally and many months later.

Yet anyone who grew up in the Soviet Union (like Putin) will have been fed the myth – and as part of it the story of the 26 Baku Bolshevik commissars murdered in cold blood on the orders of Reginald Teague-Jones. He spent the rest of his life in fear of Russian revenge, and the fear wasn’t an idle one, as the fates of men like Litvinenko and Skripal in our own time remind us •

This interview was originally published December 12, 2025.

Mavericks: Empire, Oil, Revolution and the Forgotten Battle of World War One

Bloomsbury, 9 October 2025

RRP: £25 | ISBN: 978-1526677013

“Almost as good as finding an unpublished novel” – The Lady

The forgotten story of a group of British mavericks who took on an impossible mission with a daring and fearless approach.

As the First World War drew to a close and regimes began to collapse across Europe, British officials plotted a daring campaign to send an unlikely band of maverick soldiers, diplomats and spies to the chaotic region around the Caspian Sea. Their mission: to block the advance of the Turks, to hold back the rising Bolsheviks and prevent a Turkish-inspired jihad overwhelming India, and to secure the vital supply of oil from Baku.

It was an almost impossible task, but Mavericks tells the gripping stories of the remarkable and enterprising characters at the centre of it all, who would be tested to the limit. There was Lionel Dunsterville, the inspiration for Kipling's Stalky and commander of the expedition; Ranald MacDonell, a Scottish aristocrat and diplomat who smuggled millions of roubles for the war effort; Edward Noel, a seemingly indestructible soldier who was held hostage for sixty-five days in horrific conditions; Toby Rawlinson, the younger brother of one of Britain's most senior generals and a brilliant inventor; and Reginald Teague-Jones, a spy who printed his own currency and would eventually emerge as an author at the age of ninety-nine.

Drawing on personal diaries, memoirs and once-secret government archives, Mavericks brings to life a cast of eccentric heroes who survived against all odds to tell their extraordinary tales. This is a propulsive story of boldness and intrigue, set in a forgotten corner of the Great War where the rules were made to be broken.

“Any new book on Jane Austen raises the urgent question, Would I get more pleasure from reading this than from re-reading my favourite Jane Austen novel? If you decide to give What Matters in Jane Austen? a chance you'll know after a few pages that you've made the right choice”

– Sunday Times

With thanks to Jonny Coward.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store