Mill District, Pittsburgh: Searching for the Source

We search for the source of this classic image by one of the twentieth century's great documentary photographers

"Delano’s photographs elevate the ordinary individual to heroic status." — International Center of Photography

To illustrate our recent feature on Martha Dodd we used a striking photograph of the interior of Union Station in Chicago. It was a suspenseful black and white from the mid-1940s.

The composition looks out over several rows of dimly-lit waiting benches. On these people wait and read and chat. The focus, however, rests on two uniformed figures in the foreground. These are picked out of the gloom by one of the many dazzling tunnels of sunlight that stream down from the windows above, picking out the silhouetted men as elegantly as if they were spotlights in a theatre.

This photograph was taken by Jack Delano. He is an intriguing figure in the history of photography. Born in Ukraine in 1914, his family arrived in New York as migrants shortly before his ninth birthday. Thereafter they went to live in Philadelphia where Delano grew up, like so many others of his time, as a first-generation American. He enrolled for a period at the Pennsylvanian Academy of the Fine Arts and, as America plunged into the bleakest years of what later would be remembered as the Great Depression, Delano became keenly interested in photography.

While the 1930s were testing years for many, for Delano they brought a singular opportunity. One part of the raft of socially progressive programmes launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt was called the ''Resettlement Administration'. This was intended to alleviate rural poverty and it was succeeded, in 1937, by a new and generously resourced initiative: the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

Seeking to bolster public and political support, the FSA soon after created a photographic section. This unit was led by an economist named Roy Stryker, a man who understood the storytelling power of images. In the late 1930s, Stryker began to recruit photographers to capture scenes of everyday life or examples of social problems in locations across the nation. With such an archive of visual material behind him, Stryker felt that he could explain the FSA's work far more effectively.

Over the years that followed photographs began to accumulate from all corners of the United States. As one contemporary put it, the FSA photographs captured: 'the most gay and the most tragic — the cow barn, the migrant's tent, the tractor in the field, the weathered faces of men, the faces of women sagging with household drudgery ... — they are all here, photographed in their context, in relation to their environment. In rows of filing cabinets, they wait for today's planner and tomorrow's historian'.

Delano heard about the FSA photographic work through his interactions with the Federal Theater Program. In 1940 he was taken on by Stryker and in the months that followed he spent some weeks in his home state, photographing the grit and grain of daily life in Pittsburgh.

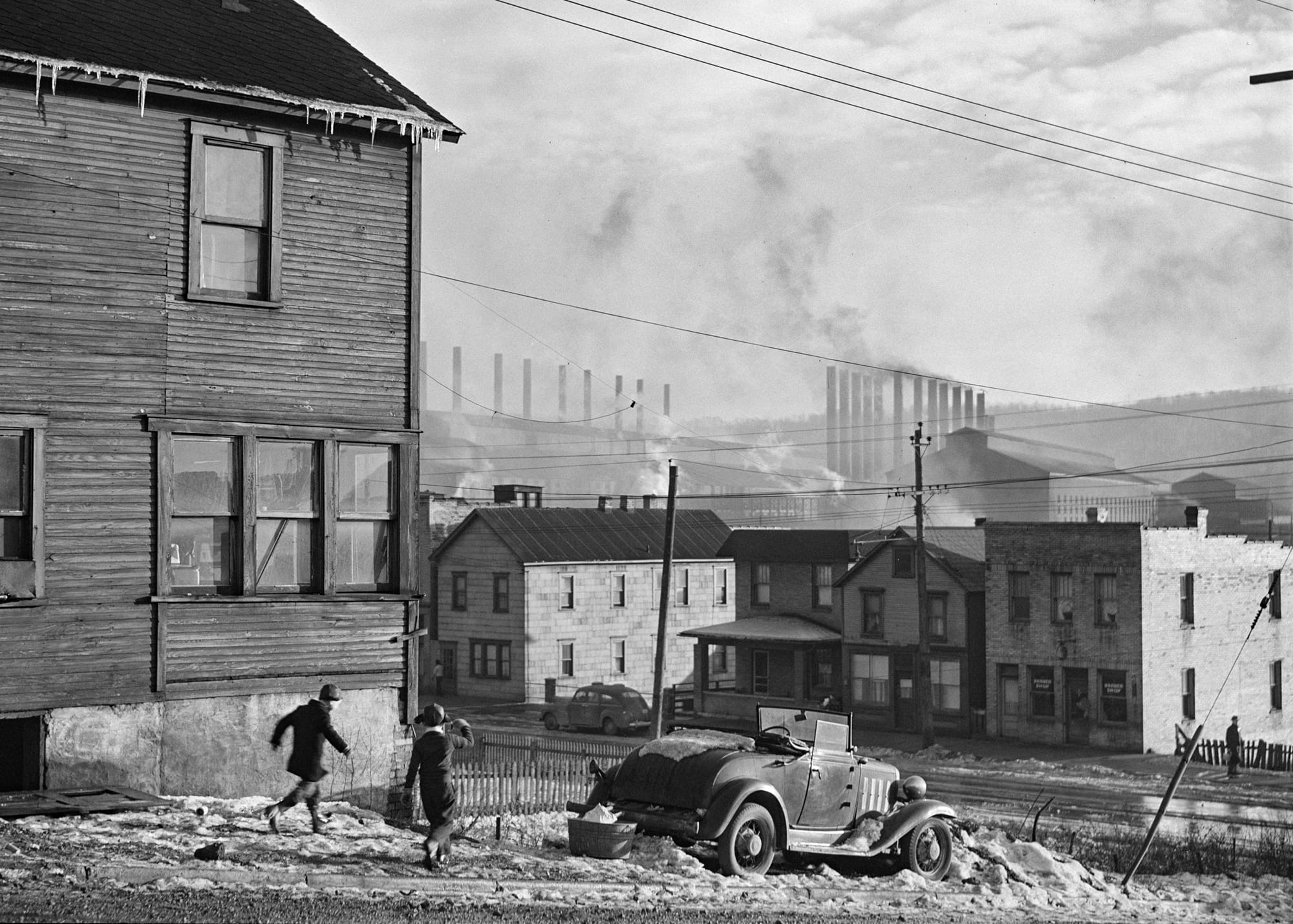

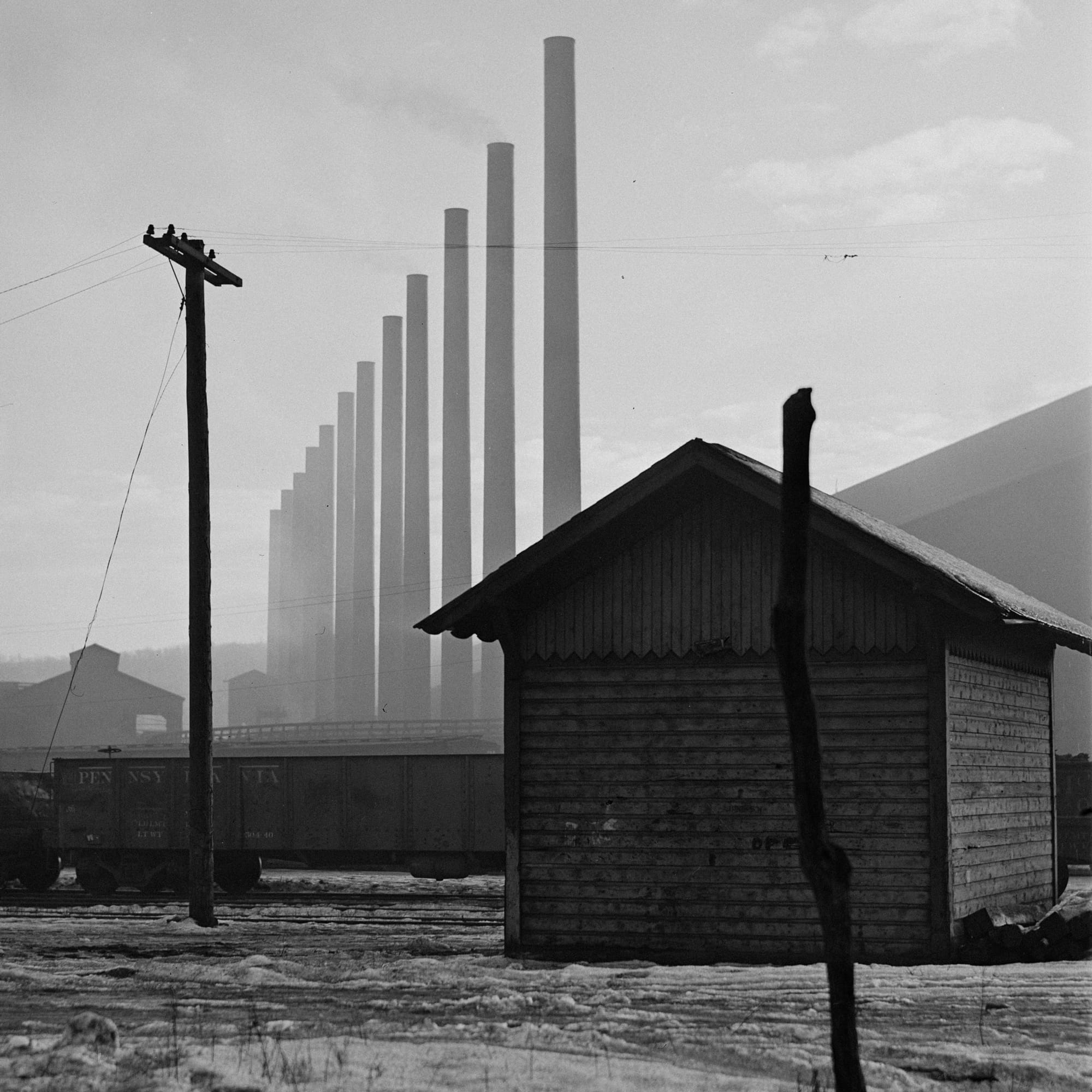

A selection of Jack Delano's photographs. These were taken during the winter of 1941 while on assignment in Pittsburgh. (⇲ Public Domain)

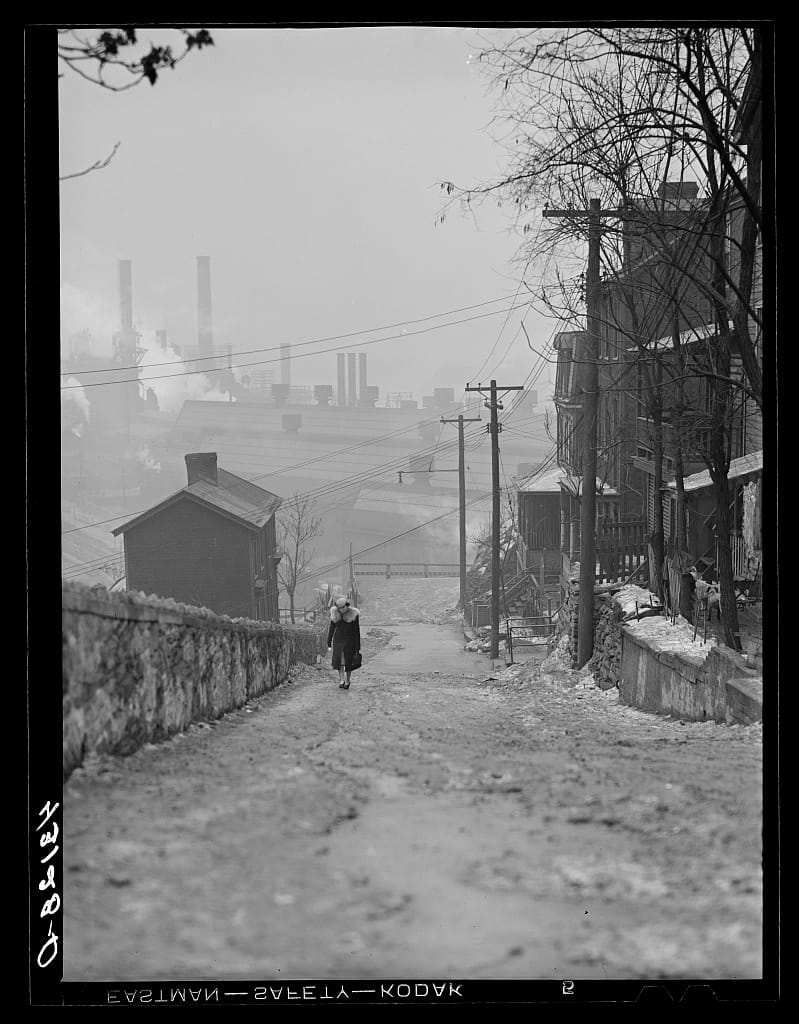

One of Delano's photographs has particularly caught Jordan J. Lloyd's eye here at Unseen Histories. It was titled 'Street in the Mill District in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania' and it showed a lady clambering up a steep hill. Behind her, the chimneys of the steel mills rise high into the hazy January sky.

'It was just an extraordinary picture. It was one of those pictures that really encapsulated the industrial heartland of America at the time. And it was that contrast between working class houses and the fog of industry behind it on this very cold January day in Pittsburgh.

I just thought that the woman walking up the slope almost looked a little bit out of place. She's actually dressed very well. She got a fur stole around her. She's got a nice well-made coat and a beret. I thought the juxtaposition of the lone figure with the factories in the background and the housing and the weather — I thought 'wow, what a brilliant image'.

— Jordan J. Lloyd

Research is the critical first part of colourising an image. So much depends on telling little details — What exact clothes are the subjects wearing? What are the weather conditions? What time of year (indeed, in which year) was the photograph taken? How are the natural and human-made factors combined to create the exact quality of light?

With the fur coat, the smoke from the chimneys and the archival and biographical records about Delano and his assignment, there were many hints to follow as we sought to properly understand the historical context behind the photograph.

One puzzle, however, did remain. Where precisely was it taken? This was a mystery that took some time to unravel. After a few false trails, the answer was revealed by the chimneys in the background.

These no longer exist but they feature clearly on a map of the city made in the 1930s as well as on aerial photographs that were made at the time.

I was looking at the relationship of the chimneys with the roofs, which turned out to be depots or a railway siding. I eventually narrowed it down to a street which is no longer there. When you see the map it is quite clearly marked.

— Jordan J. Lloyd

Left Original photograph Right Image 'blocked in' with areas of different colour demarcated for colourisation

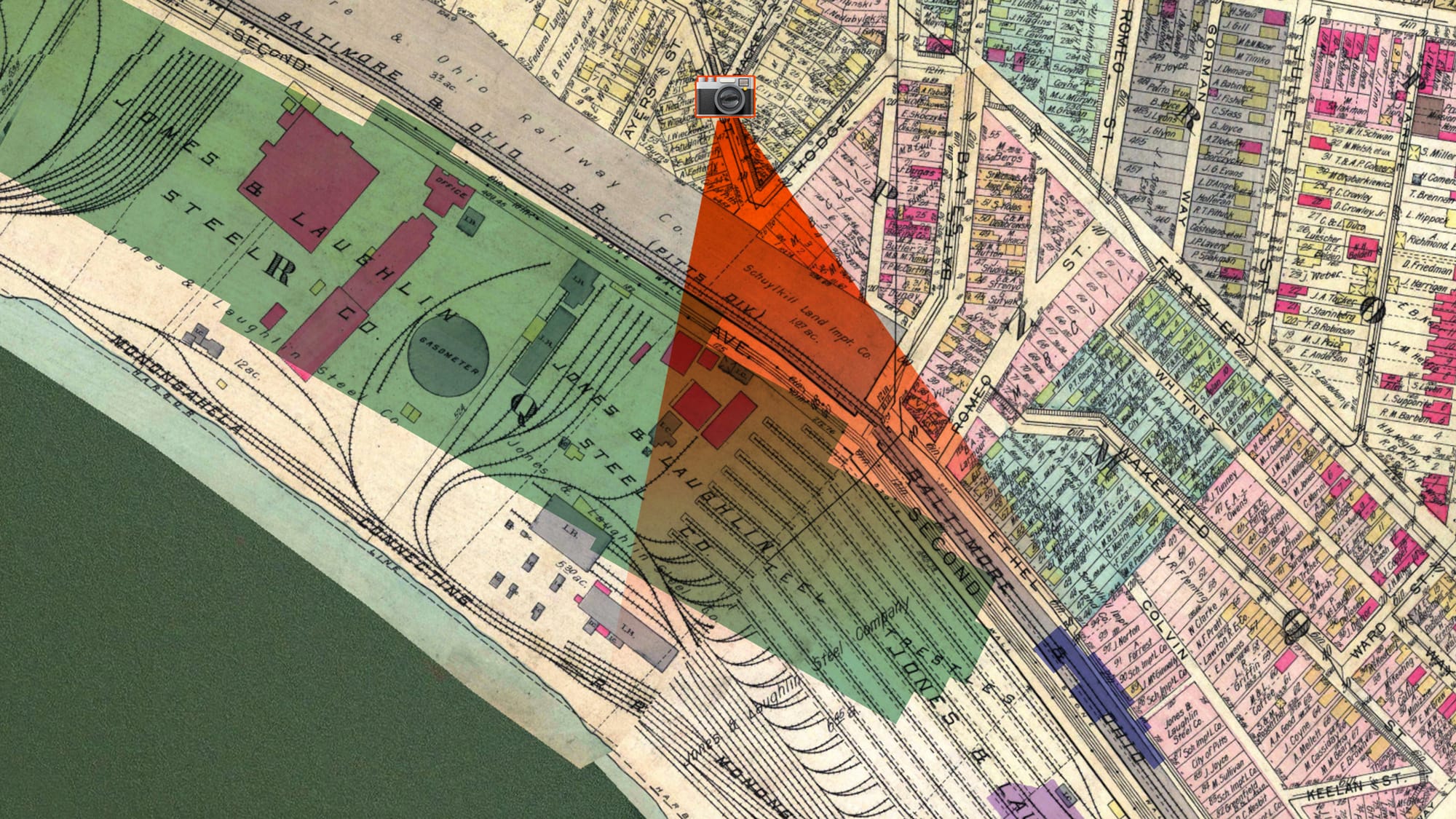

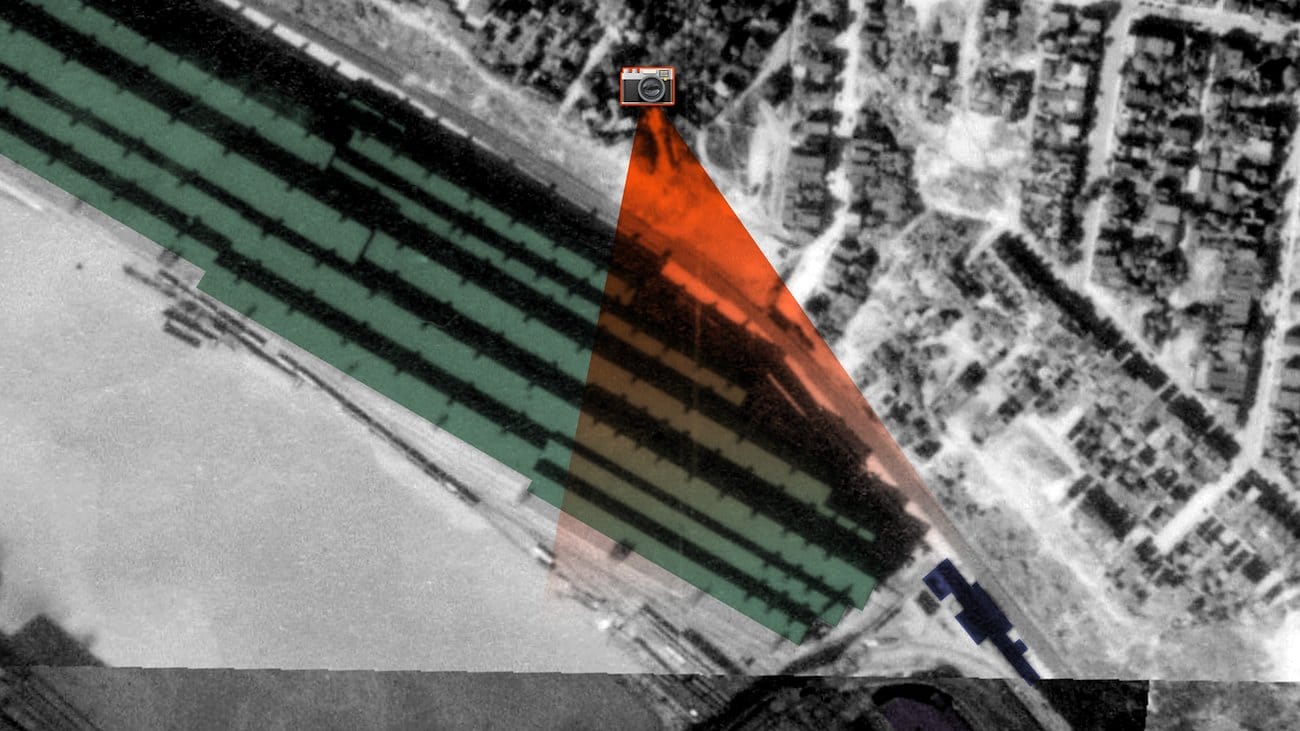

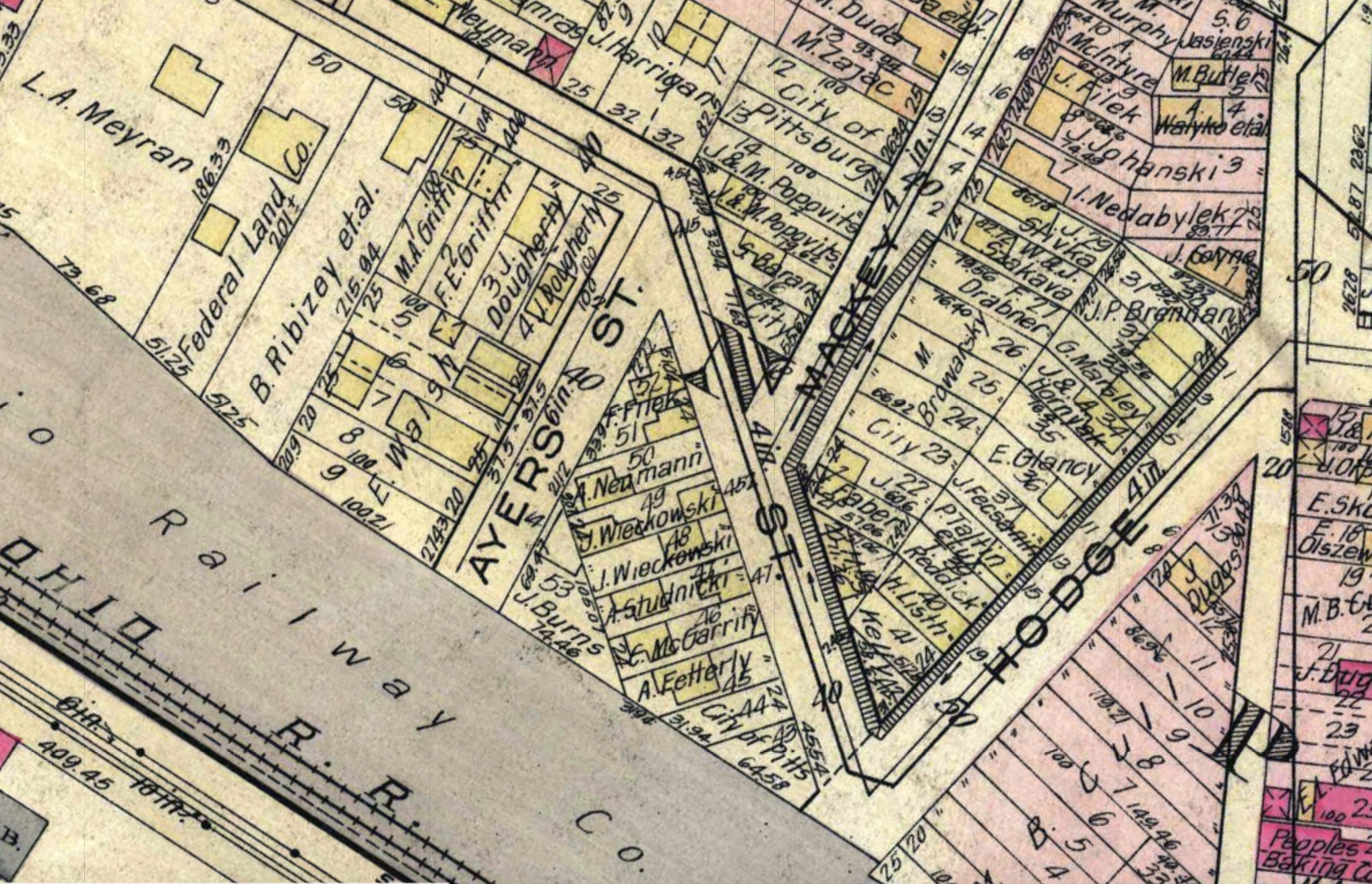

The two images directly above here show a little of the background research that went into locating the site of Delano's photograph. The first depicts a map made in 1923 with our estimate of his position marked by an icon of a camera. Beneath this is an aerial photograph from 1939 — just a few years before the shot was taken — with the line of the chimney superimposed for reference.

From these documentary sources, a clear picture does appear. You can see from the angle of the sheds, as well as the curve of the railway track on the left, that Delano has set up his tripod at the eastern end of Lawn Street as it juts down towards Hodge Street.

Studying the map still further reveals his location more precisely. For Delano seems to be standing at just the point where Mackey Street formerly fed into Lawn Street. As there's no sign of Mackay Street in the photograph, one can deduce that its opening lies just to the left of the depicted view.

Owing to the detail embedded in the 1923 map, there's still more social history that can be gleaned here. The tracks, for instance, are the tracks of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The tell-tale chimneys belong to the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company. Newspapers explain that in 1939 Jones & Laughlin were entering an exciting moment in their development, having become the first steel producer in the world to use photo-electric cells (or Bessemer Converters) in its production methods.

While the occupants of various houses shifted frequently in working-class districts like this, we can at least discern from the map that this was an area filled with Irish and Eastern European families. A Mr E. McGarrity may well have been living up the flight of wooden stairs on the right, while the houses closer to where Delano stood had been occupied in recent memory by a Mr. J. Więckowski. It may even be his red handkerchief, pinned up outside.

This is the kind of fascinating information that often turns up when working on an image. In this case, it helped frame the vision of Delano as a photographer at work. We can picture him as a young man of twenty-six on an exciting new assignment. We can see him rising early in on a bitter January morning, striking out towards the railway and the steel mills, then climbing a roughshod track as he sought to gain some elevation for a composition.

There, with little snatches of Polish to his right and the traffic of Mackey Street to his left, it seemed that he found just the place that he had been looking for. All he had to do was assemble his equipment and lie in wait for the perfect subject to appear — one who would bring colour, meaning and dynamism to an already attractive composition.

Luckily for Delano, the ideal person soon turned up.

The Mill District was an unsettled, transient area when Delano visited it. An interesting feature of the various maps is how quickly the various street names shifted. Lawn Street of 1923 had been Carolina Street a little more than a decade before and it was Charles Street not long before that. Mackay Street, meanwhile, had long been called Morris Street and it is entertaining to think of these names changing as various migrants sought to pronounce them.

Today Lawn Street, Mackay Street and Hodge Street can all still be found in Pittsburgh, but they peter out before they reach the place where Delano stood in 1941. Were someone to recreate his shot today, they would catch little more than a clump of trees, a lonely house and a road to nowhere.

Highway 22, meanwhile, roars along the track of the old Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. And in the distance, where the chimneys once rose, the name Hot Metal Bridge is the last little reminder of a neighbourhood that has now vanished completely. 𖨠

The view today. We can't go further down what was the end of Lawn Street to the exact spot where Delano took the photograph, but the retaining wall running up the entire street can still be seen in this modern street view.

Jack Delano (1914–1997) was a Ukrainian-born American photographer, illustrator, and composer, best known for his work with the Farm Security Administration (FSA) during the Great Depression. His striking images documented the lives of rural Americans, often highlighting themes of resilience and community.